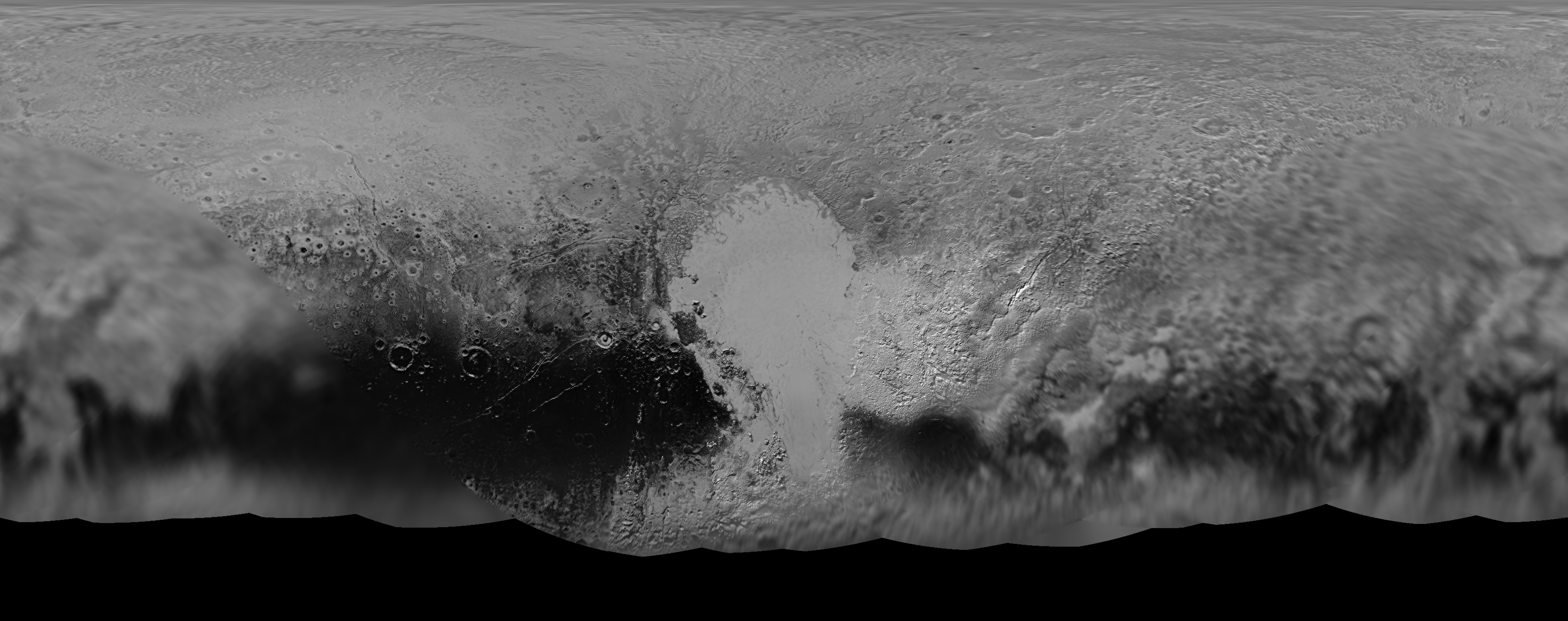

The science team leading NASA’s New Horizons mission that unveiled the true nature of Pluto’s long hidden looks during the history making maiden close encounter last July, have published a fresh global map that offers the sharpest and most spectacular glimpse yet of the mysterious, icy world.

The newly updated global Pluto map is comprised of all the highest resolution images transmitted back to Earth thus far and provides the best perspective to date.

Click on the lead image above to enjoy Pluto revealed at its finest thus far. Click on this link to view the highest resolution version.

Prior to the our first ever flyby of the Pluto planetary system barely 8 months ago, the planet was nothing more than a fuzzy blob with very little in the way of identifiable surface features – even in the most powerful telescopic views lovingly obtained from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST).

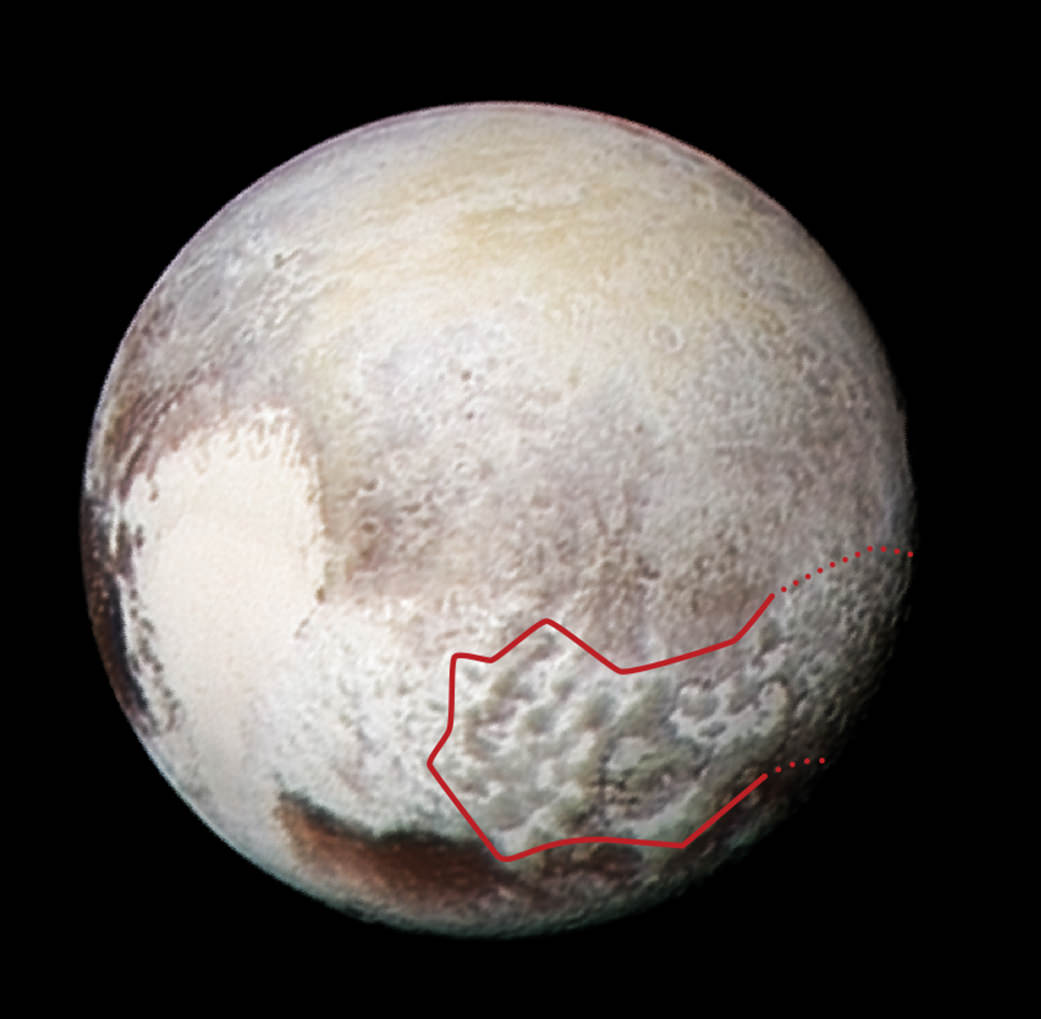

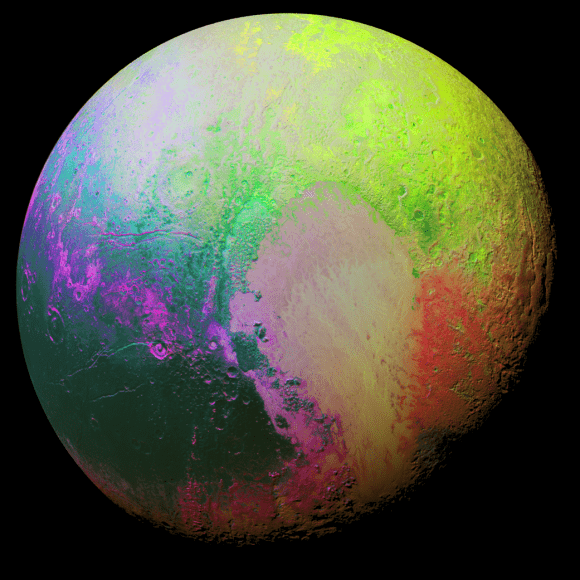

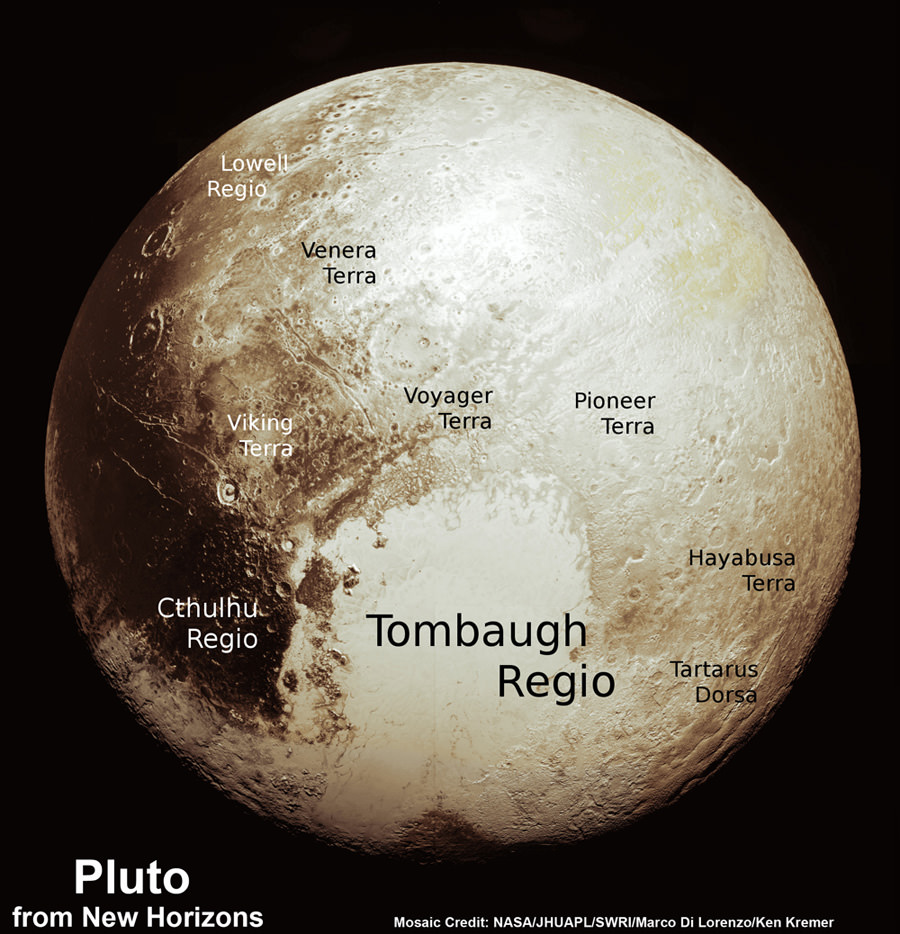

Dead center in the new map is the mesmerizing heart shaped region informally known as Tombaugh Regio, unveiled in all its glory and dominating the diminutive world.

The panchromatic (black-and-white) global map of Pluto published by the team includes the latest images received as of less than one week ago on April 25.

The images were captured by New Horizons’ high resolution Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI).

The science team is working on assembling an updated color map.

During its closest approach at approximately 7:49 a.m. EDT (11:49 UTC) on July 14, 2015, the New Horizons spacecraft swoop to within about 12,500 kilometers (nearly 7,750 miles) of Pluto’s surface and about 17,900 miles (28,800 kilometers) from Charon, the largest moon.

The map includes all resolved images of Pluto’s surface acquired in the final week of the approach period ahead of the flyby starting on July 7, and continuing through to the day of closest approach on July 14, 2015 – and transmitted back so far.

The pixel resolutions are easily seen to vary widely across the map as you scan the global map from left to right – depending on which Plutonian hemisphere was closest to the spacecraft during the period of close flyby.

They range from the highest resolution of 770 feet (235 meters), at center, to 18 miles (30 kilometers) at the far left and right edges.

The Charon-facing hemisphere (left and right edges of the map) had a pixel resolution of 18 miles (30 kilometers).

“This non-encounter hemisphere was seen from much greater range and is, therefore, in far less detail,” noted the team.

However the hemisphere facing New Horizons during the spacecraft’s closest approach on July 14, 2015 (map center) had a far higher pixel resolution reaching to 770 feet (235 meters).

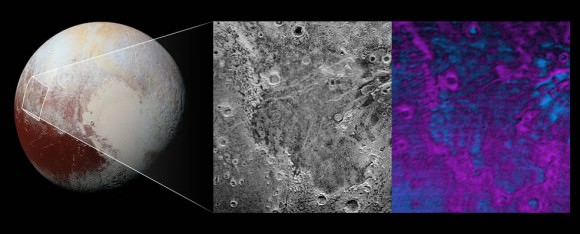

Coincidentally and fortuitously the spectacularly diverse terrain of Tombaugh Regio and the Sputnik Planum area of the hearts left ventricle with ice flows and volcanoes, mountains and river channels was in the region facing the camera and sports the highest resolution imagery.

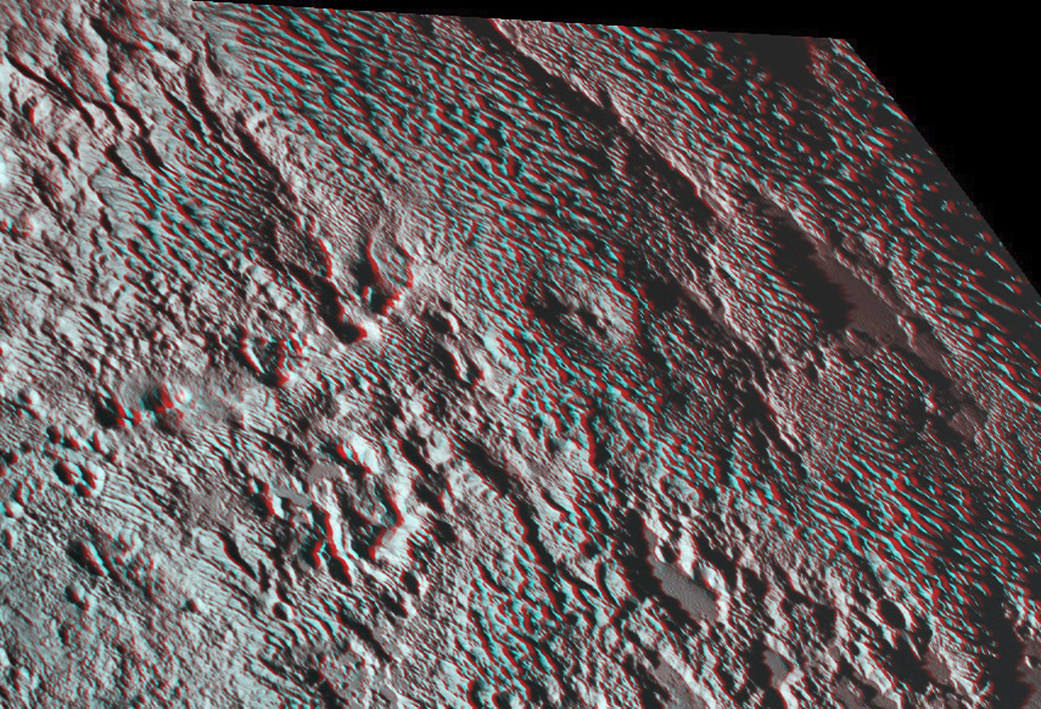

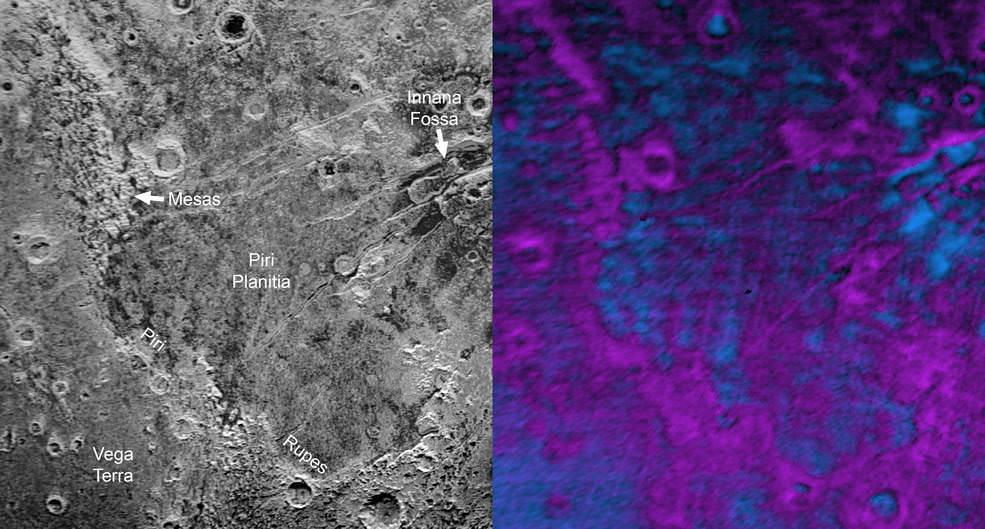

See below a newly released shaded relief map of Sputnik Planum.

“Sputnik Planum – shows that the vast expanse of the icy surface is on average 2 miles (3 kilometers) lower than the surrounding terrain. Angular blocks of water ice along the western edge of Sputnik Planum can be seen “floating” in the bright deposits of softer, denser solid nitrogen,” according to the team.

Even more stunning images and groundbreaking data will continue streaming back from New Horizons until early fall, across over 3 billion miles of interplanetary space.

Thus the global map of Pluto will be periodically updated.

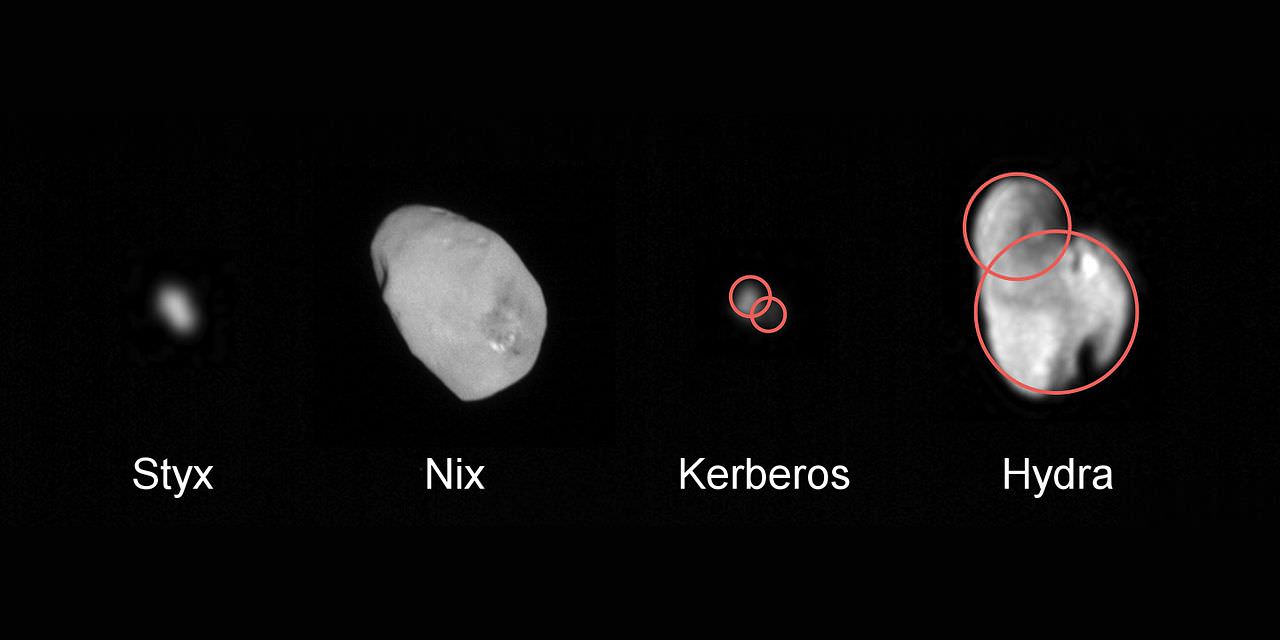

Its taking over a year to receive the full complement of some 50 gigabits of data due to the limited bandwidth available from the transmitter on the piano-shaped probe as it hurtled past Pluto, its largest moon Charon and four smaller moons.

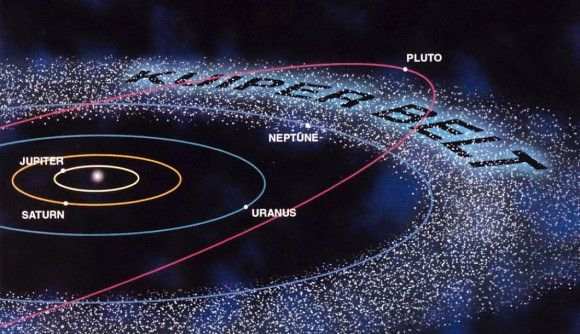

Pluto is the last planet in our solar system to be visited in the initial reconnaissance of planets by spacecraft from Earth since the dawn of the Space Age.

New Horizons remains on target to fly by a second Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) on Jan. 1, 2019 – tentatively named PT1, for Potential Target 1. It is much smaller than Pluto and was recently selected based on images taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.