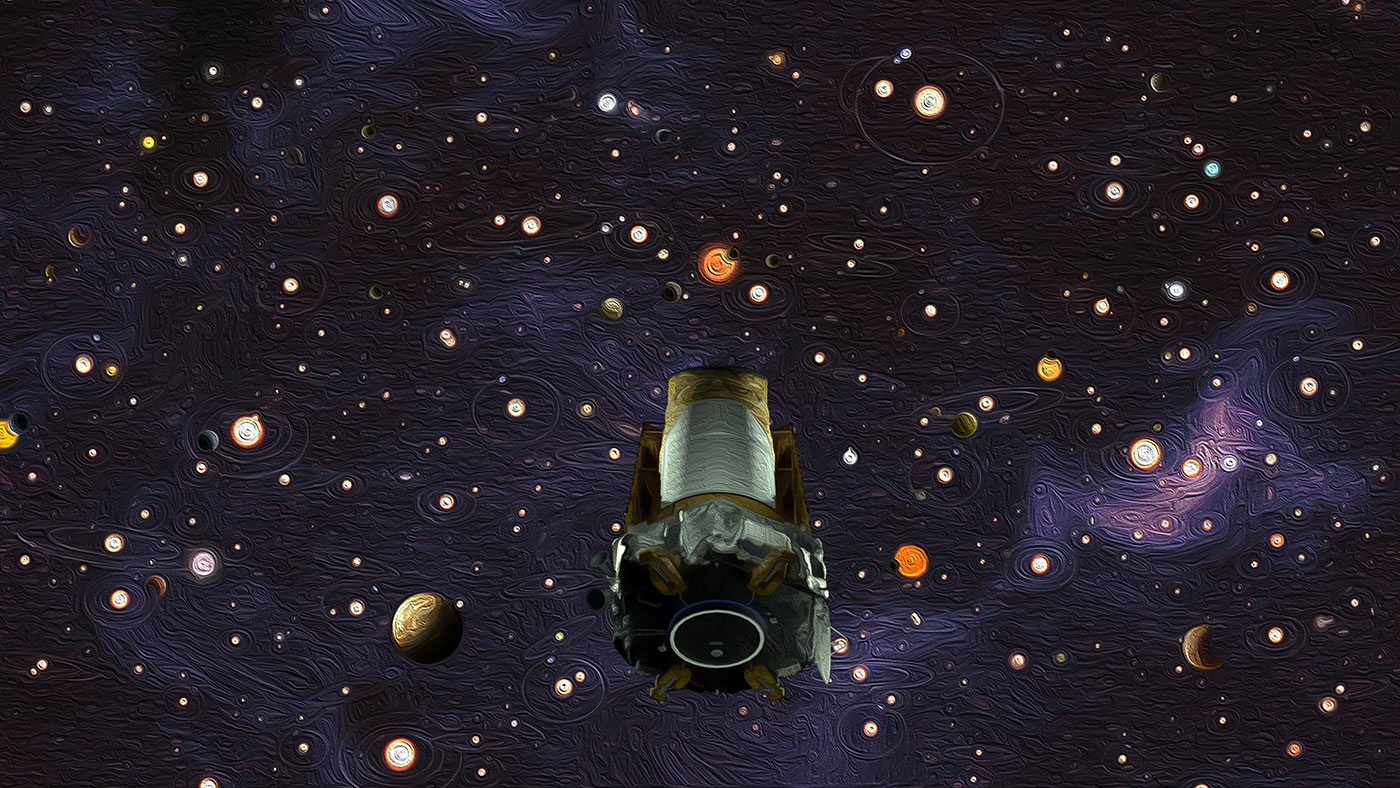

The search for exoplanets has grown immensely in recent decades thanks to next-generation observatories and instruments. The current census is 5,766 confirmed exoplanets in 4,310 systems, with thousands more awaiting confirmation. With so many planets available for study, exoplanet studies and astrobiology are transitioning from the discovery process to characterization. Essentially, this means that astronomers are reaching the point where they can directly image exoplanets and determine the chemical composition of their atmospheres.

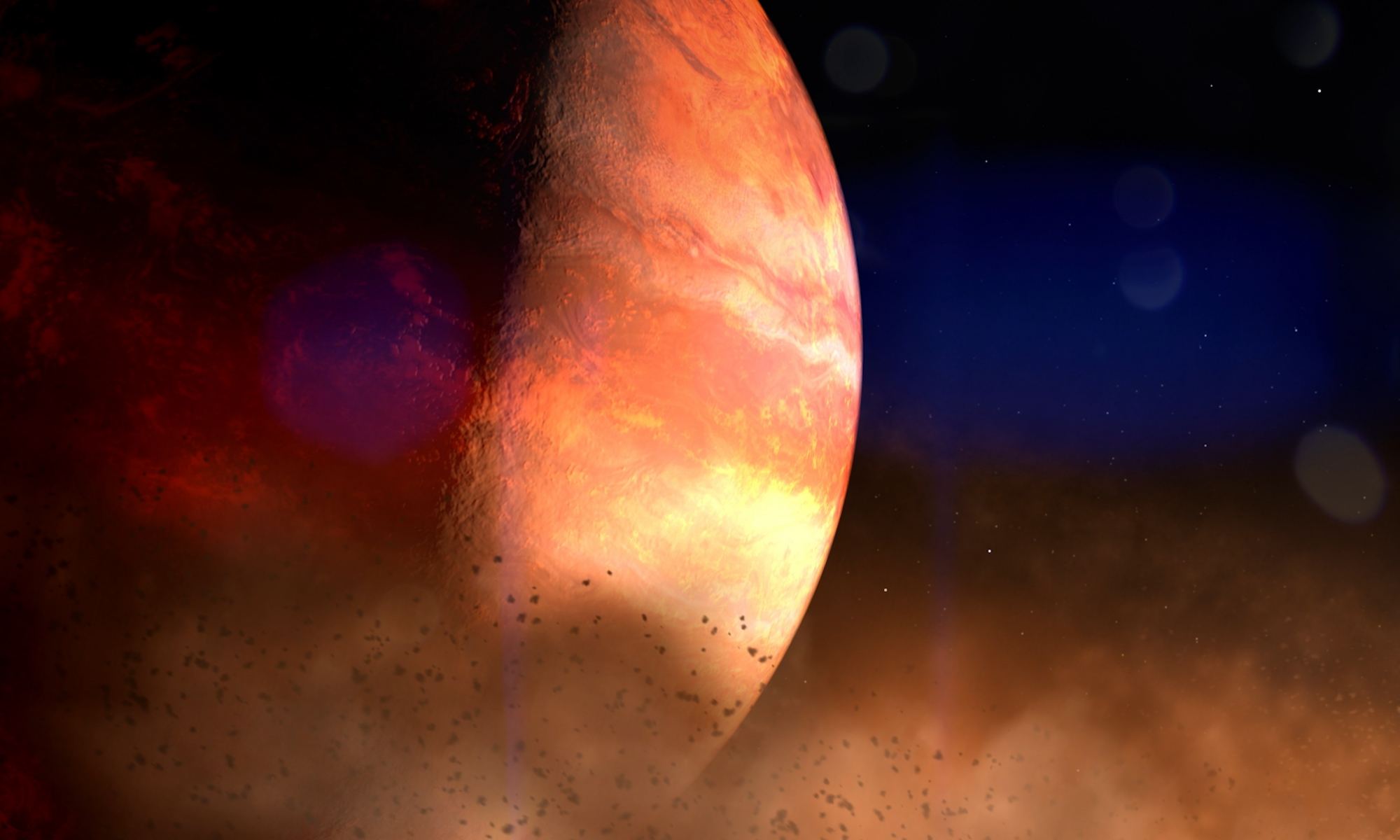

As always, the ultimate goal is to find terrestrial (rocky) exoplanets that are “habitable,” meaning they could support life. However, our notions of habitability have been primarily focused on comparisons to modern-day Earth (i.e., “Earth-like“), which has come to be challenged in recent years. In a recent study, a team of astrobiologists considered how Earth has changed over time, giving rise to different biosignatures. Their findings could inform future exoplanet searches using next-generation telescopes like the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), destined for space by the 2040s.

Continue reading “Establishing a New Habitability Metric for Future Astrobiology Surveys”