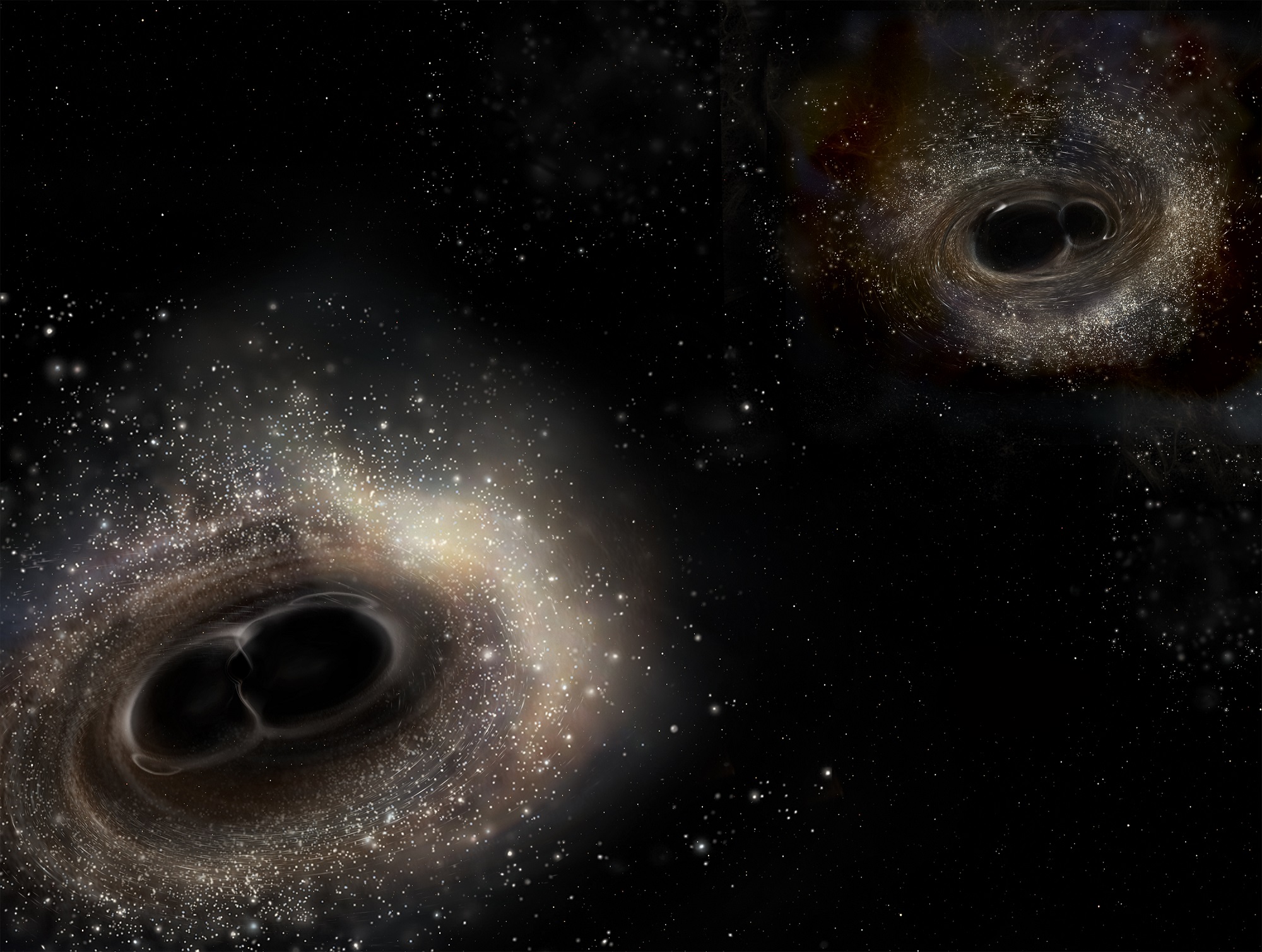

The tumultuous era of the big bang may have been chaotic enough to flood the universe with primordial black holes. Eventually some of those black holes will find each other and merge, sending out ripples of gravitational waves. A comprehensive search for those gravitational wave signatures hasn’t found anything, putting tight constraints on the abundance of these mysterious objects.

Continue reading “Gravitational-Wave Observatories Should be Able to Detect Primordial Black Hole Mergers, if They’re out There”Gravitational-Wave Detector Could Sense Merging Primordial Black Holes With the Mass of a Planet, Millions of Light-Years Away

Gravitational-wave detectors have been a part of astronomy for several years now, and they’ve given us a wealth of information about black holes and what happens when they merge. Gravitational-wave astronomy is still in its infancy, and we are still very limited in the type of gravitational waves we can observe. But that could change soon.

Continue reading “Gravitational-Wave Detector Could Sense Merging Primordial Black Holes With the Mass of a Planet, Millions of Light-Years Away”What's the Connection Between Stellar-Mass Black Holes and Dark Matter?

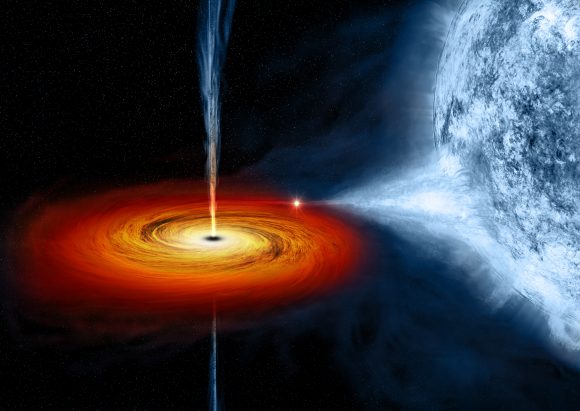

Imagine you are a neutron star. You’re happily floating in space, too old to fuse nuclei in your core anymore, but the quantum pressure of your neutrons and quarks easily keeps you from collapsing under your own weight. You look forward to a long stellar retirement of gradually cooling down. Then one day you are struck by a tiny black hole. This black hole only has the mass of an asteroid, but it causes you to become unstable. Gravity crushes you as the black hole consumes you from the inside out. Before you know it, you’ve become a black hole.

Continue reading “What's the Connection Between Stellar-Mass Black Holes and Dark Matter?”If Planet 9 is a Primordial Black Hole, We Might Be Able to See Flares When it Consumes Comets

A comet-eating black hole the size of a planet? It’s possible. And if there’s one out there in the distant Solar System, a pair of researchers think they know how to find it.

If they do, we might finally put the Planet 9 issue to rest.

Continue reading “If Planet 9 is a Primordial Black Hole, We Might Be Able to See Flares When it Consumes Comets”Planetary Mass Objects Discovered in Other Galaxies

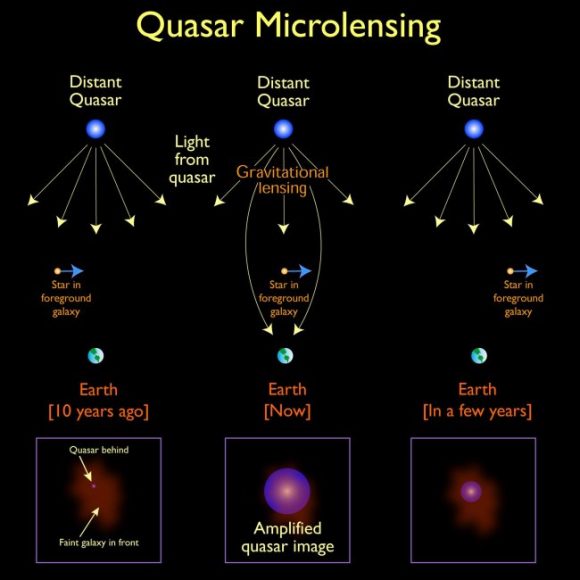

A team of researchers at the University of Oklahoma have discovered “planetary mass bodies” outside of the Milky Way. They were discovered in one gravitationally-lensed galaxy, and in one gravitationally-lensed galaxy cluster using a technique called quasar micro-lensing. According to the researchers, the planetary mass objects are either planets or primordial black holes.

Continue reading “Planetary Mass Objects Discovered in Other Galaxies”Now We Know That Dark Matter Isn’t Primordial Black Holes

For over fifty years, scientists have theorized that roughly 85% of matter in the Universe’s is made up of a mysterious, invisible mass. Since then, multiple observation campaigns have indirectly witnessed the effects that this “Dark Matter” has on the Universe. Unfortunately, all attempts to detect it so far have failed, leading scientists to propose some very interesting theories about its nature.

One such theory was offered by the late and great Stephen Hawking, who proposed that the majority of dark matter may actually be primordial black holes (PBH) smaller than a tenth of a millimeter in diameter. But after putting this theory through its most rigorous test to date, an international team of scientists led from the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (IPMU) has confirmed that it is not.

Continue reading “Now We Know That Dark Matter Isn’t Primordial Black Holes”Dark Matter Isn’t Made From Black Holes

In February of 2016, scientists working for the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made history when they announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. Since that time, multiple detections have taken place and scientific collaborations between observatories – like Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo – are allowing for unprecedented levels of sensitivity and data sharing.

This event not only confirmed a century-old prediction made by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, it also led to a revolution in astronomy. It also stoked the hopes of some scientists who believed that black holes could account for the Universe’s “missing mass”. Unfortunately, a new study by a team of UC Berkeley physicists has shown that black holes are not the long-sought-after source of Dark Matter.

Towards A New Understanding Of Dark Matter

Dark matter remains largely mysterious, but astrophysicists keep trying to crack open that mystery. Last year’s discovery of gravity waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) may have opened up a new window into the dark matter mystery. Enter what are known as ‘primordial black holes.’

Theorists have predicted the existence of particles called Weakly Interacting Massive Particles (WIMPS). These WIMPs could be what dark matter is made of. But the problem is, there’s no experimental evidence to back it up. The mystery of dark matter is still an open case file.

When LIGO detected gravitational waves last year, it renewed interest in another theory attempting to explain dark matter. That theory says that dark matter could actually be in the form of Primordial Black Holes (PBHs), not the aforementioned WIMPS.

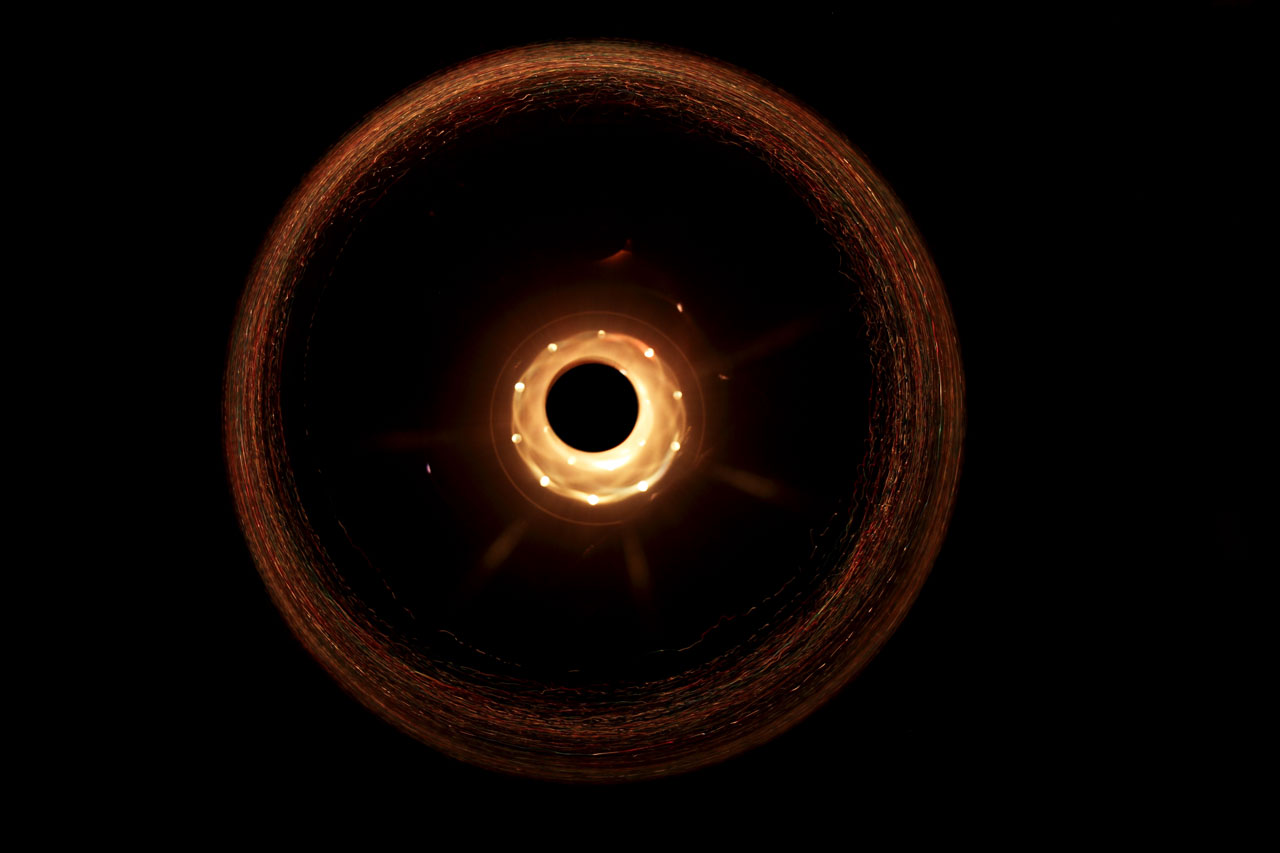

Primordial black holes are different than the black holes you’re probably thinking of. Those are called stellar black holes, and they form when a large enough star collapses in on itself at the end of its life. The size of these stellar black holes is limited by the size and evolution of the stars that they form from.

Credits: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

Unlike stellar black holes, primordial black holes originated in high density fluctuations of matter during the first moments of the Universe. They can be much larger, or smaller, than stellar black holes. PBHs could be as small as asteroids or as large as 30 solar masses, even larger. They could also be more abundant, because they don’t require a large mass star to form.

When two of these PBHs larger than about 30 solar masses merge together, they would create the gravitational waves detected by LIGO. The theory says that these primordial black holes would be found in the halos of galaxies.

If there are enough of these intermediate sized PBHs in galactic halos, they would have an effect on light from distant quasars as it passes through the halo. This effect is called ‘micro-lensing’. The micro-lensing would concentrate the light and make the quasars appear brighter.

The effect of this micro-lensing would be stronger the more mass a PBH has, or the more abundant the PBHs are in the galactic halo. We can’t see the black holes themselves, of course, but we can see the increased brightness of the quasars.

Working with this assumption, a team of astronomers at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias examined the micro-lensing effect on quasars to estimate the numbers of primordial black holes of intermediate mass in galaxies.

“The black holes whose merging was detected by LIGO were probably formed by the collapse of stars, and were not primordial black holes.” -Evencio Mediavilla

The study looked at 24 quasars that are gravitationally lensed, and the results show that it is normal stars like our Sun that cause the micro-lensing effect on distant quasars. That rules out the existence of a large population of PBHs in the galactic halo. “This study implies “says Evencio Mediavilla, “that it is not at all probable that black holes with masses between 10 and 100 times the mass of the Sun make up a significant fraction of the dark matter”. For that reason the black holes whose merging was detected by LIGO were probably formed by the collapse of stars, and were not primordial black holes”.

Depending on you perspective, that either answers some of our questions about dark matter, or only deepens the mystery.

We may have to wait a long time before we know exactly what dark matter is. But the new telescopes being built around the world, like the European Extremely Large Telescope, the Giant Magellan Telescope, and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, promise to deepen our understanding of how dark matter behaves, and how it shapes the Universe.

It’s only a matter of time before the mystery of dark matter is solved.

Primordial Black Holes, Dark Matter and Stellar Collisions… Oh, My!

[/caption]

Well, we’re off to see the Wizard again, my friends. This time it’s to explore the possibilities of primordial black holes colliding with stars and all the implications therein. If this theory is correct, then we should be able to observe the effects of dark matter first hand – proof that it really does exist – and deeper understand the very core of the Universe.

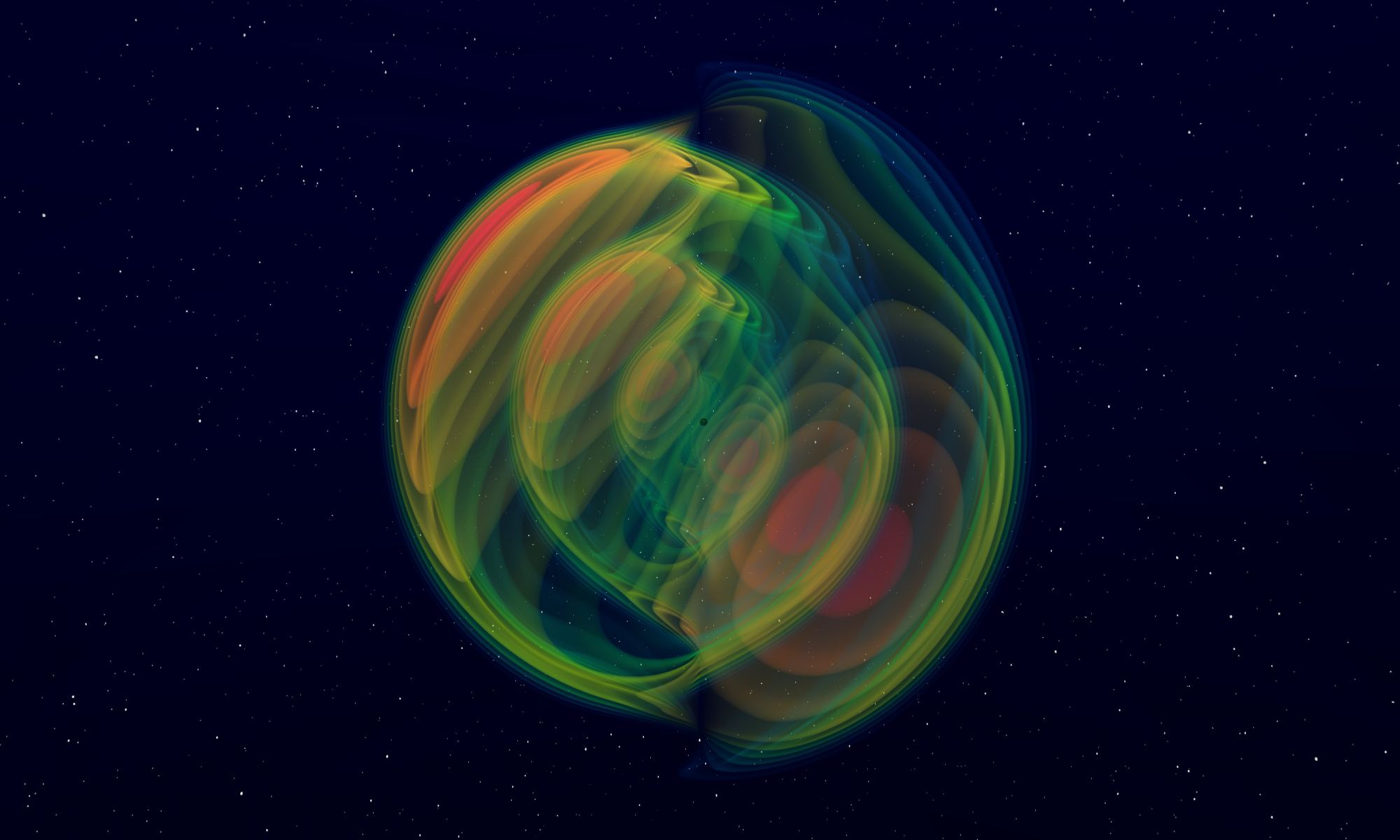

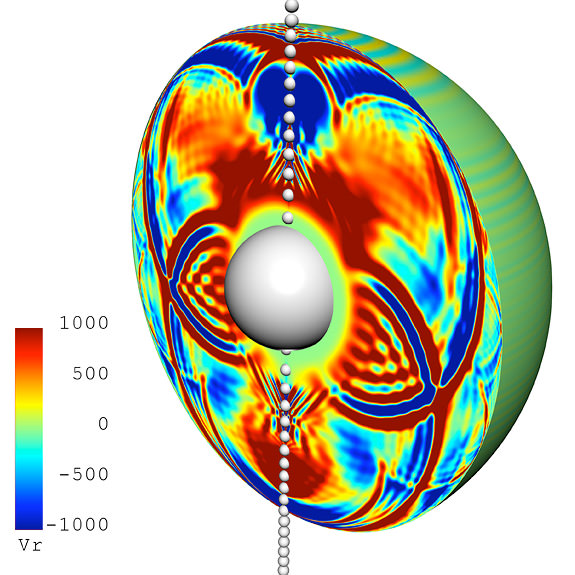

Are primordial black holes blueprints for dark matter? Postdoctoral researchers Shravan Hanasoge of Princeton’s Department of Geosciences and Michael Kesden of NYU’s Center for Cosmology and Particle Physics have utilized computer modeling to visualize a primordial black hole passing through a star. “Stars are transparent to the passage of primordial black holes (PBHs) and serve as seismic detectors for such objects.” says Kesden. “The gravitational field of a PBH squeezes a star and causes it to ring acoustically.”

If primordial black holes do exist, then chances are great that these type of collisions happen within our own galaxy – and frequently. With ever more telescopes and satellites observing the stellar neighborhoods, it only stands to reason that sooner or later we’re going to catch one of these events. But, the most important thing is simply understanding what we’re looking for. The computer model developed by Hanasoge and Kesden can be used with these current solar-observation techniques to offer a more precise method for detecting primordial black holes than existing tools.

“If astronomers were just looking at the Sun, the chances of observing a primordial black hole are not likely, but people are now looking at thousands of stars,” Hanasoge said.”There’s a larger question of what constitutes dark matter, and if a primordial black hole were found it would fit all the parameters — they have mass and force so they directly influence other objects in the Universe, and they don’t interact with light. Identifying one would have profound implications for our understanding of the early Universe and dark matter.”

Sure. We haven’t seen DM, but what we can see are galaxies that are hypothesized to have extended dark-matter halos and to study the effects the gravity has on their materials – like gaseous regions and stellar members. If these new models are correct, primordial black holes should be heavier than existing dark matter and when they collide with a star, should cause a rippling effect.

“If you imagine poking a water balloon and watching the water ripple inside, that’s similar to how a star’s surface appears,” Kesden said. “By looking at how a star’s surface moves, you can figure out what’s going on inside. If a black hole goes through, you can see the surface vibrate.”

Using the Sun as a model, Kesden and Hanasoge calculated the effects a PBH might have and then gave the data to NASA’s Tim Sandstrom. Using the Pleiades supercomputer at the agency’s Ames Research Center in California, the team was then able to create a video simulation of the collisional effect. Below is the clip which shows the vibrations of the Sun’s surface as a primordial black hole — represented by a white trail — passes through its interior.

“It’s been known that as a primordial black hole went by a star, it would have an effect, but this is the first time we have calculations that are numerically precise,” comments Marc Kamionkowski, a professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University. “This is a clever idea that takes advantage of observations and measurements already made by solar physics. It’s like someone calling you to say there might be a million dollars under your front doormat. If it turns out to not be true, it cost you nothing to look. In this case, there might be dark matter in the data sets astronomers already have, so why not look?”

I’ll race you to the door…

Original Story Source: Princeton University News. For Further Reading: Transient Solar Oscillations Driven by Primordial Black Holes.