The Solar System is filled with what are known as Trojan Asteroids – objects that share the orbit of a planet or larger moon. Whereas the best-known Trojans orbit with Jupiter (over 6000), there are also well-known Trojans orbiting within Saturn’s systems of moons, around Earth, Mars, Uranus, and even Neptune.

Until recently, Neptune was thought to have 12 Trojans. But thanks to a new study by an international team of astronomers – led by Hsing-Wen Lin of the National Central University in Taiwan – five new Neptune Trojans (NTs) have been identified. In addition, the new discoveries raise some interesting questions about where Neptune’s Trojans may come from.

For the sake of their study – titled “The Pan-STARRS 1 Discoveries of Five New Neptune Trojans“- the team relied on data obtained by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS). This wide-field imaging facility – which was founded by the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy – has spent the last decade searching the Solar System for asteroids, comets, and Centaurs.

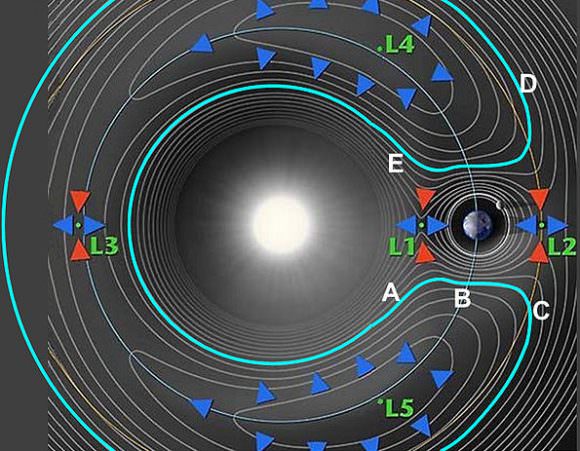

The team used data obtained by the PS-1 survey, which ran from 2010 to 2014 and utilized the first Pan-STARR telescope on Mount Haleakala, Hawaii. From this, they observed seven Trojan asteroids around Neptune, five of which were previously undiscovered. Four of the TNs were observed orbiting within Neptune’s L4 point, and one within its L5 point.

The newly detected objects have sizes ranging from 100 to 200 kilometers in diameter, and in the case of the L4 Trojans, the team concluded from the stability of their orbits that they were likely primordial in origin. Meanwhile, the lone L5 Trojan was more unstable than the other four, which led them to hypothesize that it was a recent addition.

As Professor Lin explained to Universe Today via email:

“The 2 of the 4 currently known L5 Neptune Trojans, included the one L5 we found in this work, are dynamically unstable and should be temporary captured into Trojan cloud. On the other hand, the known L4 Neptune Trojans are all stable. Does that mean the L5 has higher faction of temporary captured Trojans? It could be, but we need more evidence.”

In addition, the results of their simulation survey showed that the newly-discovered NT’s had unexpected orbital inclinations. In previous surveys, NTs typically had high inclinations of over 20 degrees. However, in the PS1 survey, only one of the newly discovered NTs did, whereas the others had average inclinations of about 10 degrees.

From this, said Lin, they derived two possible explanations:

“The L4 “Trojan Cloud” is wide in orbital inclination space. If it is not as wide as we thought before, the two observational results are statistically possible to generate from the same intrinsic inclination distribution. The previous study suggested >11 degrees width of inclination, and most likely is ~20 degrees. Our study suggested that it should be 7 to 27 degrees, and the most likely is ~ 10 degrees.”

“[Or], the previous surveys were used larger aperture telescopes and detected fainter NT than we found in PS1. If the fainter (smaller) NTs have wider inclination distribution than the larger ones, which means the smaller NTs are dynamically “hotter” than the larger NTs, the disagreement can be explained.”

According to Lin, this difference is significant because the inclination distribution of NTs is related to their formation mechanism and environment. Those that have low orbital inclinations could have formed at Neptune’s Lagrange Points and eventually grew large enough to become Trojans asteroids.

On the other hand, wide inclinations would serve as an indication that the Trojans were captured into the Lagrange Points, most likely during Neptune’s planetary migration when it was still young. And as for those that have wide inclinations, the degree to which they are inclined could indicate how and where they would have been captured.

“If the width is ~ 10 degrees,” he said, “the Trojans can be captured from a thin (dynamically cold) planetesimal disk. On the other hand, if the Trojan cloud is very wide (~ 20 degrees), they have to be captured from a thick (dynamically hot) disk. Therefore, the inclination distribution give us an idea of how early Solar system looks like.”

In the meantime, Li and his research team hope to use the Pan-STARR facility to observe more NTs and hundreds of other Centaurs, Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) and other distant Solar System objects. In time, they hope that further analysis of other Trojans will shed light on whether there truly are two families of Neptune Trojans.

This was all made possible thanks to the PS1 survey. Unlike most of the deep surveys, which are only ale to observe small areas of the sky, the PS1 is able to monitor the whole visible sky in the Northern Hemisphere, and with considerable depth. Because of this, it is expected to help astronomers spot objects that could teach us a great deal about the history of the early Solar System.

Further Reading: arXiv