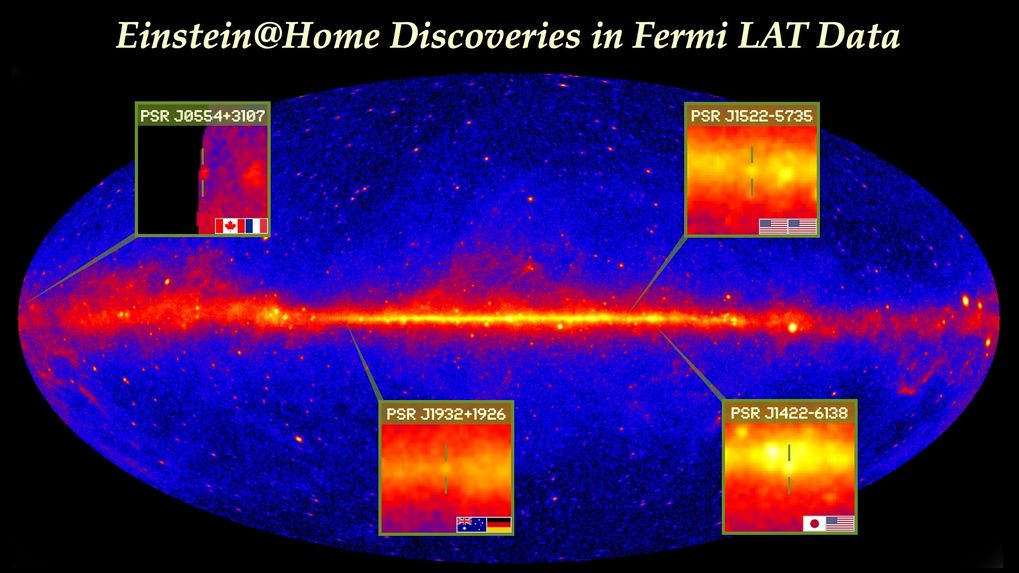

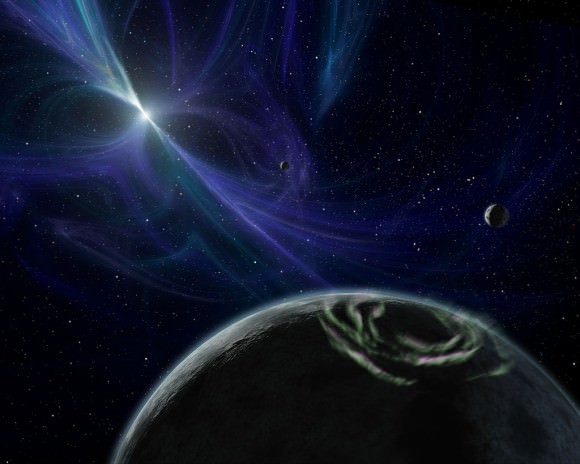

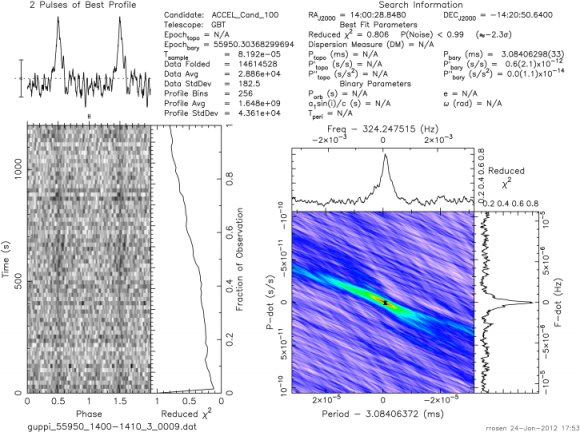

The galactic center is a happening place, with lots of gas, dust, stars, and surprising binary stars orbiting a supermassive black hole about three million times the size of our sun. With so many stars, astronomers estimate that there should be hundreds of dead ones. But to date, scientists have found only a single young pulsar at the galactic center where there should be as many as 50.

The question thus arises: where are all those rapidly spinning, dense stellar corpses known as pulsars? Joseph Bramante of Notre Dame University and astrophysicist Tim Linden of the University of Chicago have a possible solution to this missing-pulsar problem, which they describe in a paper accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Maybe those pulsars are absent because dark matter, which is plentiful in the galactic center, gloms onto the pulsars, accumulating until the pulsars become so dense they collapse into a black hole. Basically, they disappeared into the fabric of space and time by becoming so massive that they punched a hole right through it.

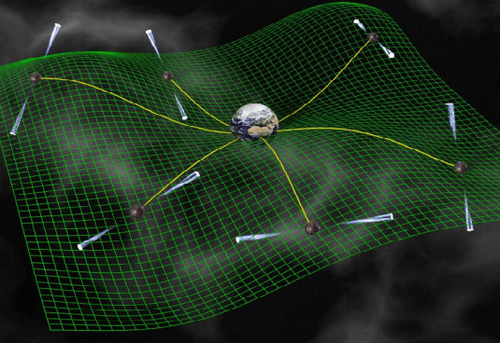

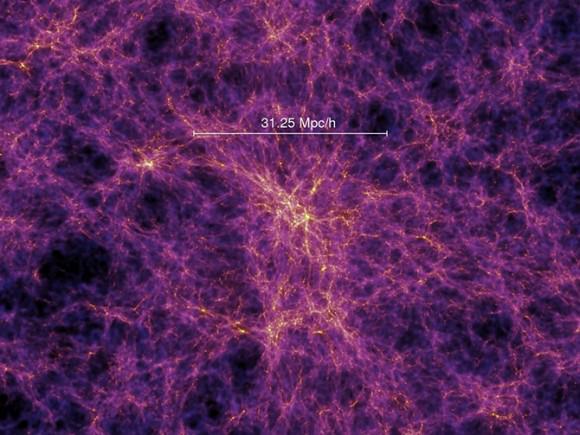

Dark matter, as you may know, is the theoretical mass that astrophysicists believe fills roughly a quarter of our universe. Alas, it is invisible and undetectable by conventional means, making its presence known only in how its gravitational pull interacts with other stellar objects.

One of the more popular candidates for dark matter is Weakly Interacting Massive Particles, otherwise known as WIMPs. Underground detectors are currently hunting for WIMPs and debate has raged over whether gamma rays streaming from the galactic center come from WIMPs annihilating one another.

In general, any particle and its antimatter partner will annihilate each other in a flurry of energy. But WIMPs don’t have an antimatter counterpart. Instead, they’re thought to be their own antiparticles, meaning that one WIMP can annihilate another.

But over the last few years, physicists have considered another class of dark matter called asymmetric dark matter. Unlike WIMPs, this type of dark matter does have an antimatter counterpart.

Asymmetric dark matter appeals to physicists because it’s intrinsically linked to the imbalance of matter and antimatter. Basically, there’s a lot more matter in the universe than antimatter – which is good considering anything less than an imbalance would lead to our annihilation. Likewise, according to the theory, there’s much more dark matter than anti-dark-matter.

Physicists think that in the beginning, the Big Bang should’ve created as much matter as antimatter, but something altered this balance. No one’s sure what this mechanism was, but it might have triggered an imbalance in dark matter as well – hence it is “asymmetric”.

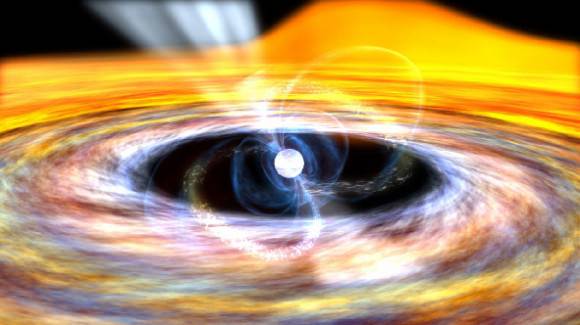

Dark matter is concentrated at the galactic center, and if it’s asymmetric, then it could collect at the center of pulsars, pulled in by their extremely strong gravity. Eventually, the pulsar would accumulate so much mass from dark matter that it would collapse into a black hole.

The idea that dark matter can cause pulsars to implode isn’t new. But the new research is the first to apply this possibility to the missing-pulsar problem.

If the hypothesis is correct, then pulsars around the galactic center could only get so old before grabbing so much dark matter that they turn into black holes. Because the density of dark matter drops the farther you go from the center, the researchers predict that the maximum age of pulsars will increase with distance from the center. Observing this distinct pattern would be strong evidence that dark matter is not only causing pulsars to implode, but also that it’s asymmetric.

“The most exciting part about this is just from looking at pulsars, you can perhaps say what dark matter is made of,” Bramante said. Measuring this pattern would also help physicists narrow down the mass of the dark matter particle.

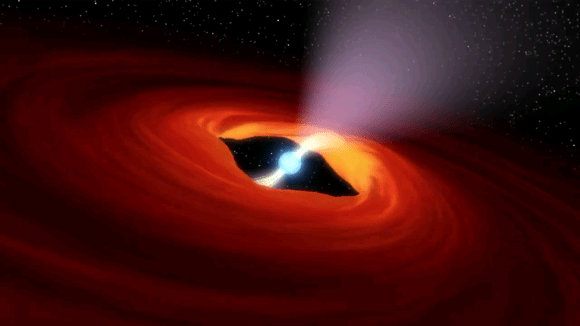

Credit: NASA, Caltech-JPL

But as Bramante admits, it won’t be easy to detect this signature. Astronomers will need to collect much more data about the galactic center’s pulsars by searching for radio signals, he claims. The hope is that as astronomers explore the galactic center with a wider range of radio frequencies, they will uncover more pulsars.

But of course, the idea that dark matter is behind the missing pulsar problem is still highly speculative, and the likelihood of it is being called into question.

“I think it’s unlikely—or at least it is too early to say anything definitive,” said Zurek, who was one of the first to revive the notion of asymmetric dark matter in 2009. The tricky part is being able to know for sure that any measurable pattern in the pulsar population is due to dark-matter-induced collapse and not something else.

Even if astronomers find this pulsar signature, it’s still far from being definitive evidence for asymmetric dark matter. As Kathryn Zurek of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory explained: “Realistically, when dark matter is detected, we are going to need multiple, complementary probes to begin to be convinced that we have a handle on the theory of dark matter.”

And asymmetric dark matter may not have anything to do with the missing pulsar problem at all. The problem is relatively new, so astronomers may find more plausible, conventional explanations.

“I’d say give them some time and maybe they come up with some competing explanation that’s more fleshed out,” Bramante said.

Nevertheless, the idea is worth pursuing, says Haibo Yu of the University of California, Riverside. If anything, this analysis is a good example of how scientists can understand dark matter by exploring how it may influence astrophysical objects. “This tells us there are ways to explore dark matter that we’ve never thought of before,” he said. “We should have an open mind to see all possible effects that dark matter can have.”

There’s one other way to determine if dark matter can cause pulsars to implode: To catch them in the act. No one knows what a collapsing pulsar might look like. It might even blow up.

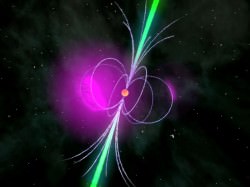

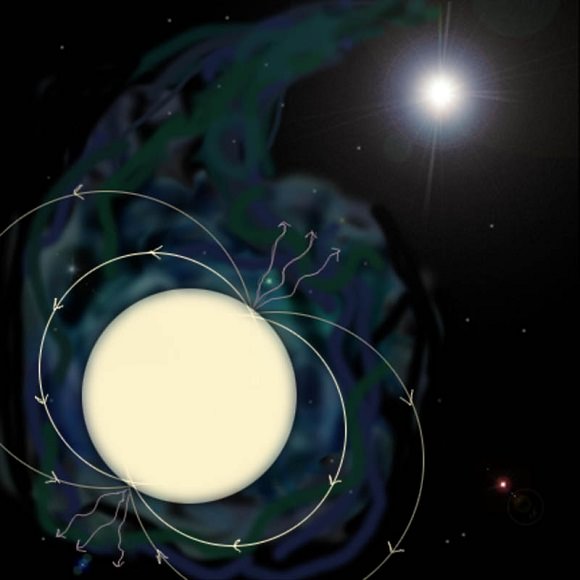

“While the idea of an explosion is really fun to think about, what would be even cooler is if it didn’t explode when it collapsed,” Bramante said. A pulsar emits a powerful beam of radiation, and as it spins, it appears to blink like a lighthouse with a frequency as high as several hundred times per second. As it implodes into a black hole, its gravity gets stronger, increasingly warping the surrounding space and time.

Studying this scenario would be a great way to test Einstein’s theory of general relativity, Bramante says. According to theory, the pulse rate would get slower and slower until the time between pulses becomes infinitely long. At that point, the pulses would stop entirely and the pulsar would be no more.

Further Reading: APS Physics, WIRED