[/caption]

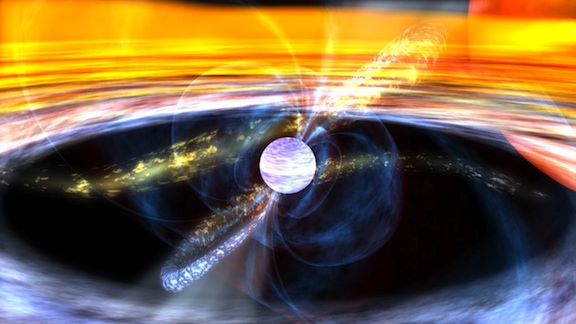

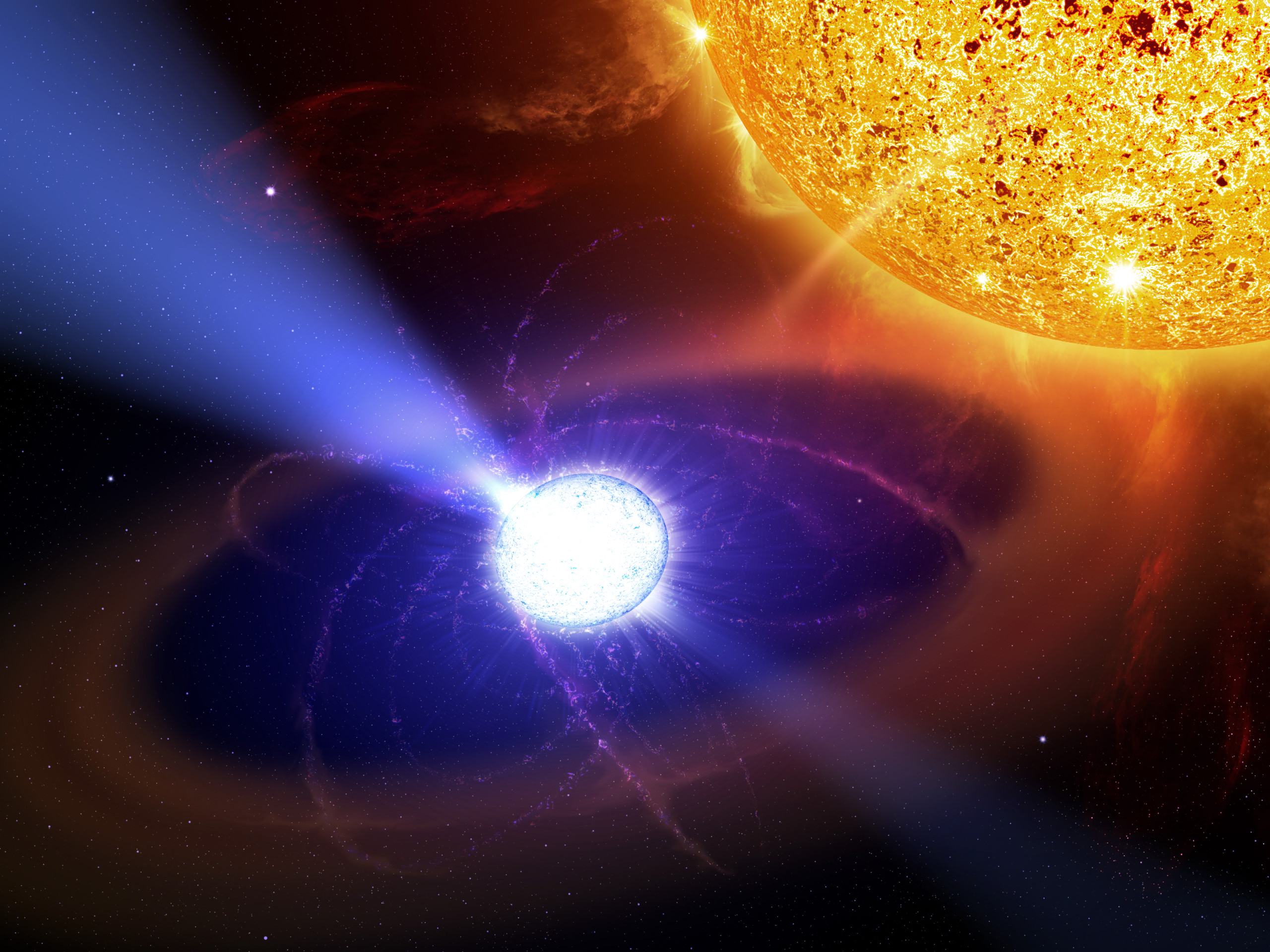

Neutron stars have been classed as “undead”… real zombie stars. Even though technically defunct, the neutron star continues to shine – and occasionally feed on a neighbor if it gets too close. They are born when a massive star collapses under its gravity and its outer layers are blown far and wide, outshining a billion suns, in a supernova event. What’s left is a stellar corpse… a core of inconceivable density… where one teaspoon would weigh about a billion tons on Earth. How would we study such a curiosity? NASA has proposed a mission called the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) that would detect the zombie and allow us to see into the dark heart of a neutron star.

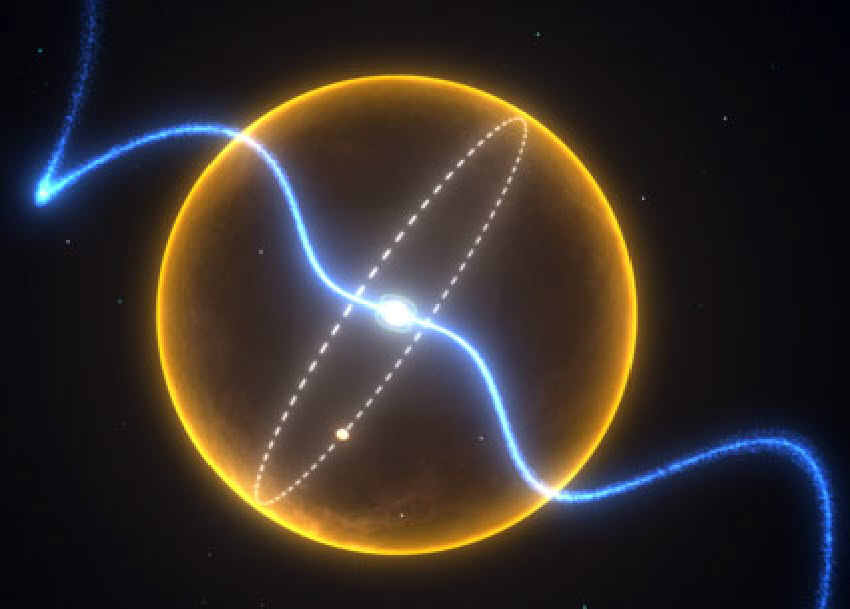

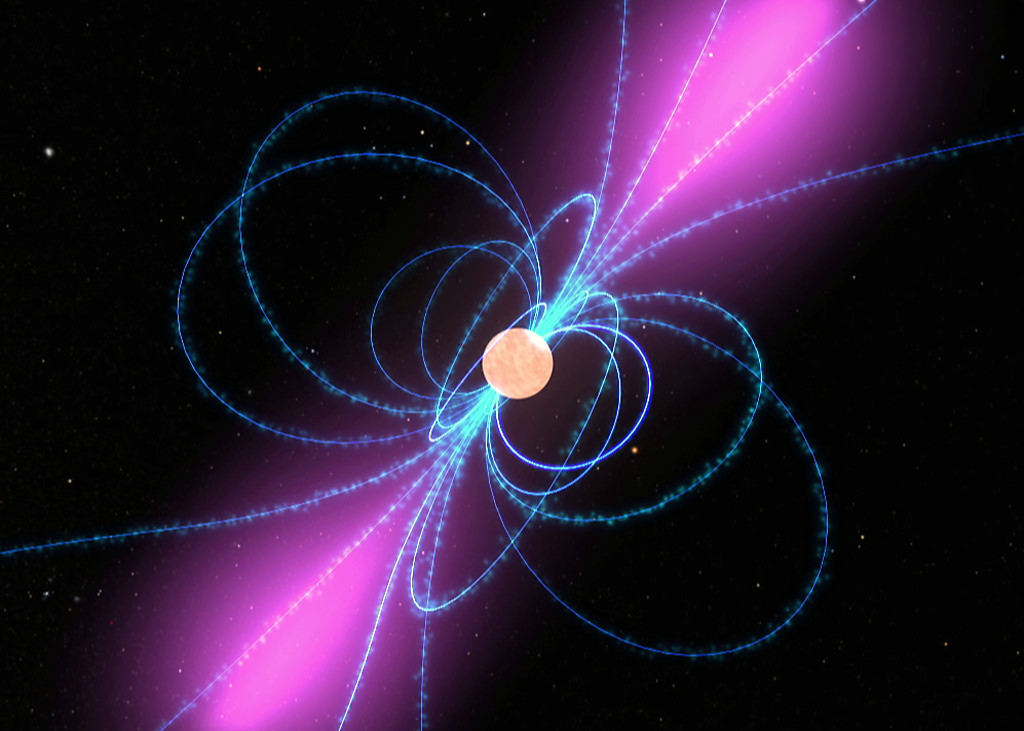

The core of a neutron star is pretty incredible. Despite the fact that it has blown away most of its exterior and stopped nuclear fusion, it still radiates heat from the explosion and exudes a magnetic field which tips the scales. This intense form of radiation caused by core collapse measures out at over a trillion times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field. If you don’t think that impressive, then think of the size. Originally the star could have been a trillion miles or more in diameter, yet now is compressed to the size of an average city. That makes a neutron star a tiny dynamo – capable of condensing matter into itself at more than 1.4 times the content of the Sun, or at least 460,000 Earths.

“A neutron star is right at the threshold of matter as it can exist – if it gets any denser, it becomes a black hole,” says Dr. Zaven Arzoumanian of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We have no way of creating neutron star interiors on Earth, so what happens to matter under such incredible pressure is a mystery – there are many theories about how it behaves. The closest we come to simulating these conditions is in particle accelerators that smash atoms together at almost the speed of light. However, these collisions are not an exact substitute – they only last a split second, and they generate temperatures that are much higher than what’s inside neutron stars.”

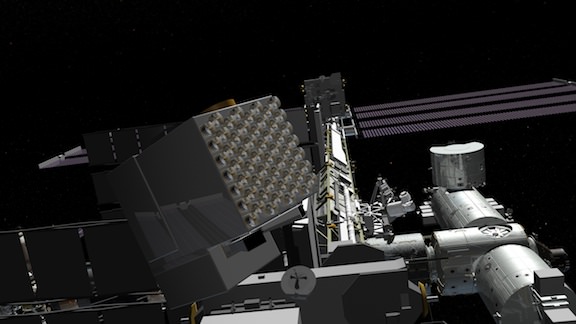

If approved, the NICER mission will be launched by the summer of 2016 and attached robotically to the International Space Station. In September 2011, NASA selected NICER for study as a potential Explorer Mission of Opportunity. The mission will receive $250,000 to conduct an 11-month implementation concept study. Five Mission of Opportunity proposals were selected from 20 submissions. Following the detailed studies, NASA plans to select for development one or more of the five Mission of Opportunity proposals in February 2013.

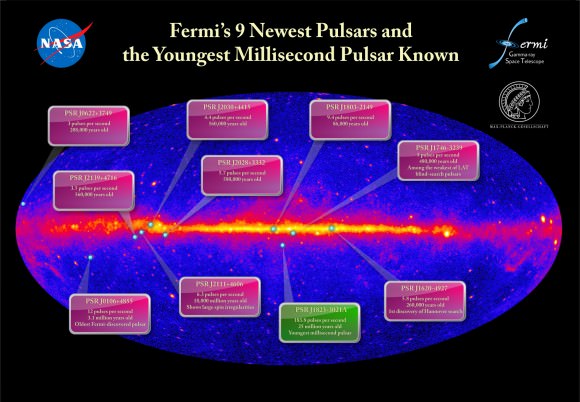

What will NICER do? First off, an array of 56 telescopes will gather X-ray information from a neutron stars magnetic poles and hotspots. It is from these areas that our zombie stars release X-rays, and as they rotate create a pulse of light – thereby the term “pulsar”. As the neutron star shrinks, it spins faster and the resultant intense gravity can pull in material from a closely orbiting star. Some of these pulsars spin so fast they can reach speeds of several hundred of rotations per second! What scientists are itching to understand is how matter behaves inside a neutron star and “pinning down the correct Equation Of State (EOS) that most accurately describes how matter responds to increasing pressure. Currently, there are many suggested EOSs, each proposing that matter can be compressed by different amounts inside neutron stars. Suppose you held two balls of the same size, but one was made of foam and the other was made of wood. You could squeeze the foam ball down to a smaller size than the wooden one. In the same way, an EOS that says matter is highly compressible will predict a smaller neutron star for a given mass than an EOS that says matter is less compressible.”

Now all NICER will need to do is help us to measure a pulsar’s mass. Once it is determined, we can get a correct EOS and unlock the mystery of how matter behaves under intense gravity. “The problem is that neutron stars are small, and much too far away to allow their sizes to be measured directly,” says NICER Principal Investigator Dr. Keith Gendreau of NASA Goddard. “However, NICER will be the first mission that has enough sensitivity and time-resolution to figure out a neutron star’s size indirectly. The key is to precisely measure how much the brightness of the X-rays changes as the neutron star rotates.”

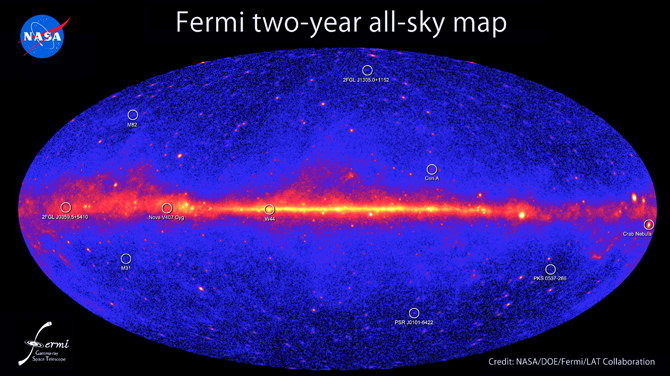

So what else does our zombie star do that’s impressive? Because of their extreme gravity in such small volume, they distort space/time in accordance with Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. It is this space “warp” that allows astronomers to reveal the presence of a companion star. It also produces effects like an orbital shift called precession, allowing the pair to orbit around each other causing gravitational waves and producing measurable orbital energy. One of the goals of NICER is to detect these effects. The warp itself will allow the team to determine the neutron star’s size. How? Imagine pushing your finger into a stretchy material – then imagine pushing your whole hand against it. The smaller the neutron star, the more it will warp space and light.

Here light curves become very important. When a neutron star’s hotspots are aligned with our observations, the brightness increases as one rotates into view and dims as it rotates away. This results in a light curve with large waves. But, when space is distorted we’re allowed to view around the curve and see the second hotspot – resulting in a light curve with smoother, smaller waves. The team has models that produce “unique light curves for the various sizes predicted by different EOSs. By choosing the light curve that best matches the observed one, they will get the correct EOS and solve the riddle of matter on the edge of oblivion.”

And breathe life into zombie stars…

Original Story Source: NASA Mission News.