[/caption]

An innovative project that provides high school students in Australia the opportunity to work with the famous Parkes radio telescope will soon make the data available to schools around the world. The PULSE@Parkes project allows for hands-on remote observing of pulsars producing real-time data, which then becomes part of a growing database used by professional astronomers. “Students can help monitor pulsars and identify unusual ones or detect sudden glitches in their rotation,” said Rob Hollow from the Australia Telescope National Facility, and coordinator for the PULSE@Parkes project. “They can also help determine the distance to existing pulsars.”

Initially, the project was only available to schools in Australia, but PULSE@Parkes hopes to expand globally, allowing students to collaborate on monitoring pulsar data. The first international session will be held on Dec. 7, 2009 at Cardiff University in the UK.

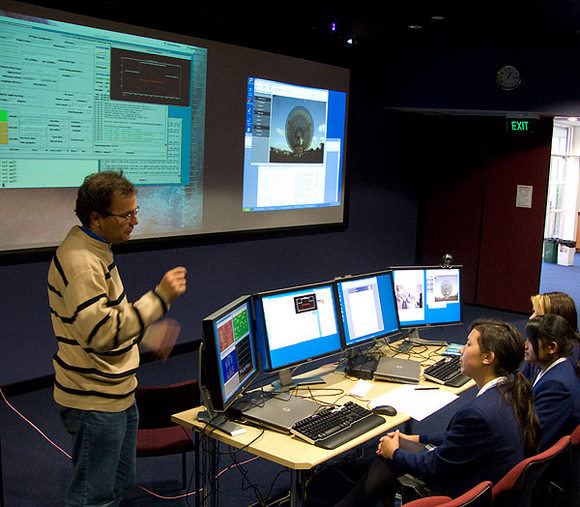

“We had the challenge to develop and implement simulation radio astronomy activities for high school students, providing the opportunity for them to actually use a radio telescope facility and engage with professional scientists,” said Hollow, speaking at the .Astronomy (dot Astronomy) conference this week in Leiden, The Netherlands. “We also wanted to have students doing science that is appropriate for them and useful for professional astronomers.”

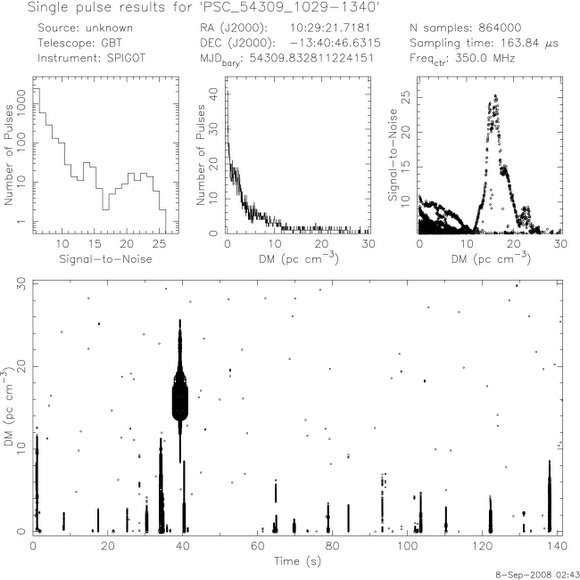

Hollow said that even though radio astronomy data consists of squiggly lines, students are still engaged by the results, even without the pretty pictures produced by other astronomical instruments. “It works surprisingly well, and the visuals haven’t been as big an issue and we thought,” Hollow said. “But in looking at pulsars, the students do get the pulse profiles and they get immediate feedback.”

Plus, when the dish actually moves in response to the students’ inputs, they really become engaged. “There’s a real ‘wow’ factor in being able to control the telescope,” Hollow said. “The students pick it up quickly, and they really like that they are contributing to science.”

Recently, the first science paper was published using results obtained by students.

The program is done remotely, and students view webcams of the telescope and control room. They control the telescope directly via the internet, monitor the data in real time, and use Skype to communicate with astronomers at Parkes.

So far, Hollow said, they have done 25 sessions, with 28 schools, working with about 450 students. “This project is not just for gift and talented students,” he said, “and any school can apply.”

Parkes is a 64 m diameter radio antenna that was built in 1961. Hollow said the dish has received regular updates and is still on the cutting edge of science. Most famously, Parkes was to receive video from the Apollo mission to the Moon.

Hollow said he sees PULSE@Parkes as just the beginning of working with students. The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) will be coming online in just a couple of years, with thirty-six 12-meter dishes. “This will provide for very fast surveys that will increase the area of coverage and increase the capability for sensitivity,” Hollow said. “From ASKAP, we’ll be getting massive data sets, which will provide more opportunity for student and public involvement.

For more information, including an audio of what a pulsar “sounds” like, as well as info for schools and teachers, requirements, and how to apply visit the PULSE@Parkes website