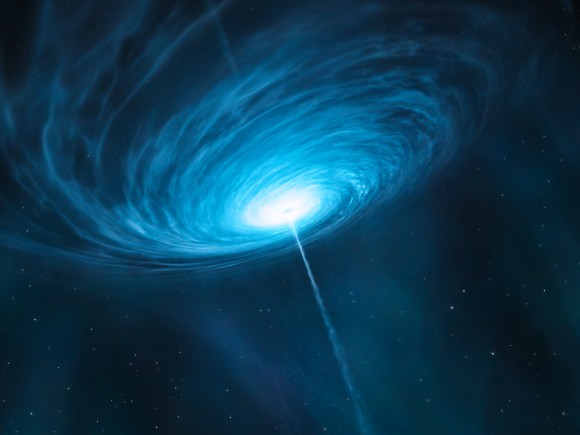

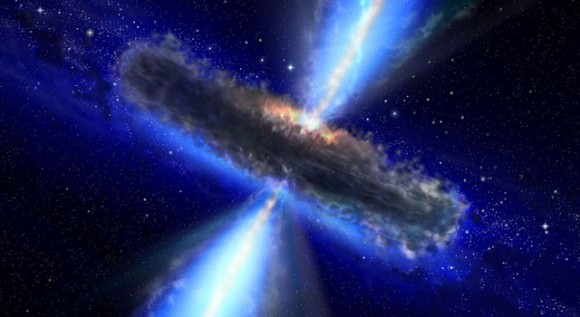

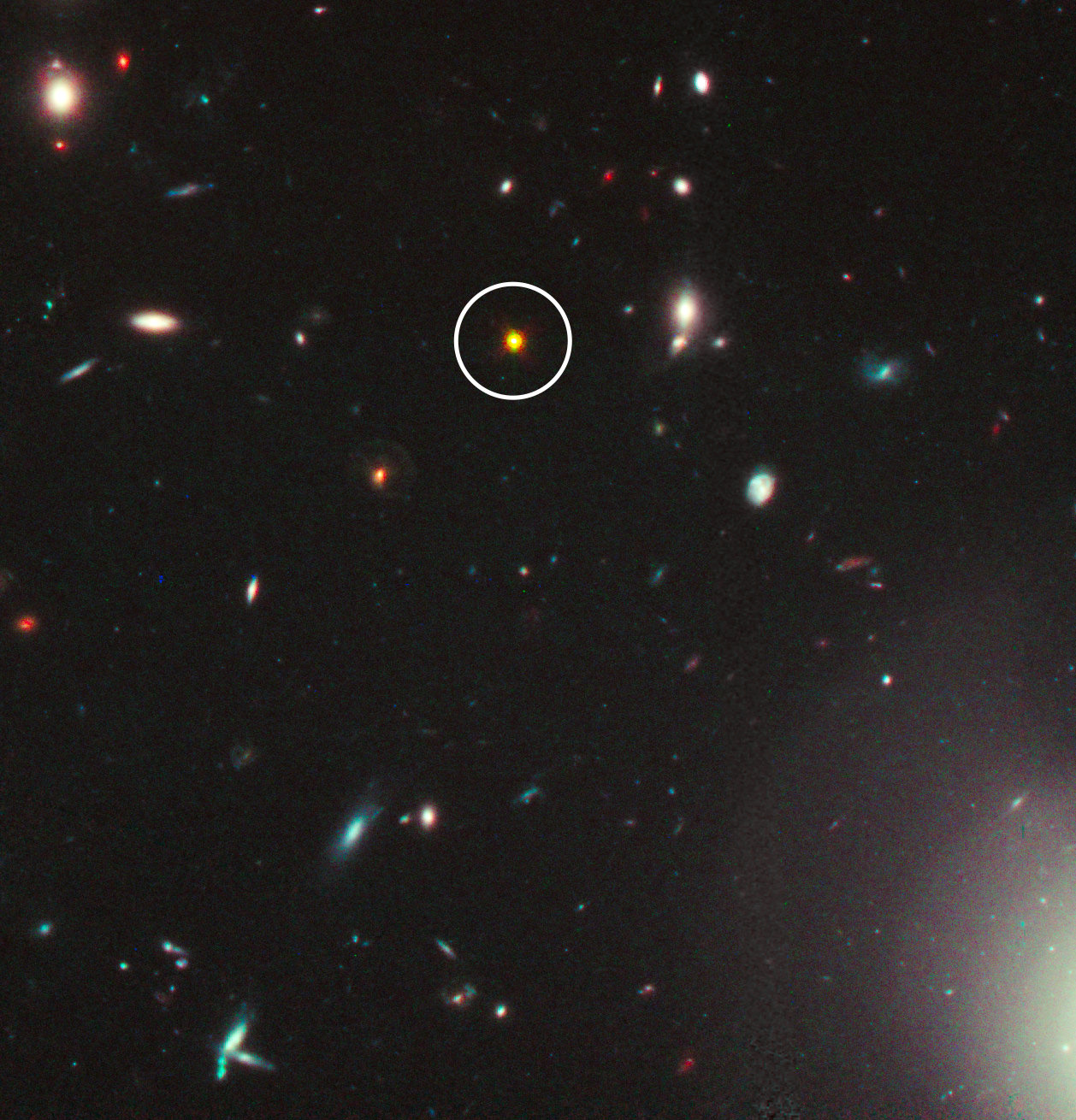

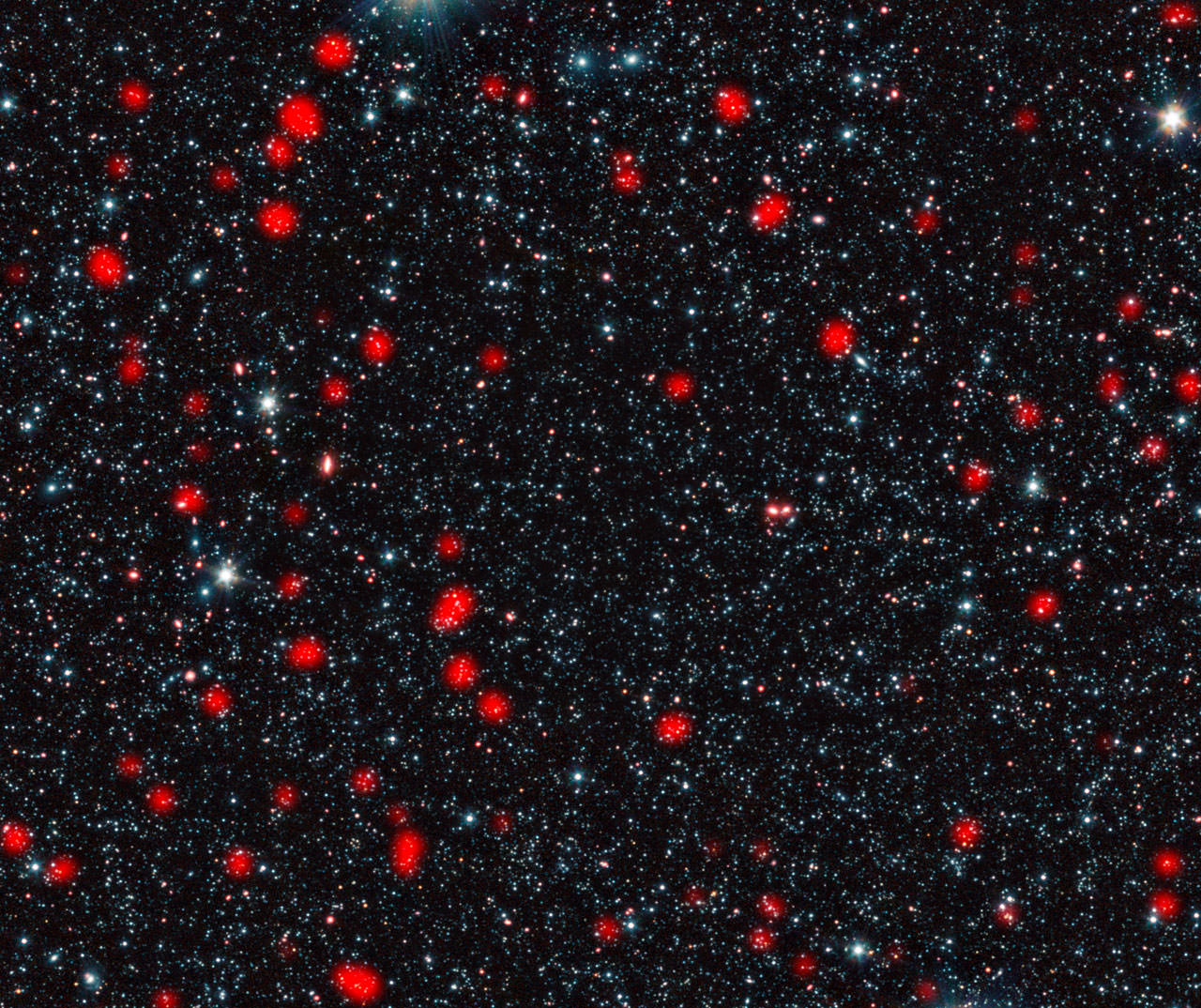

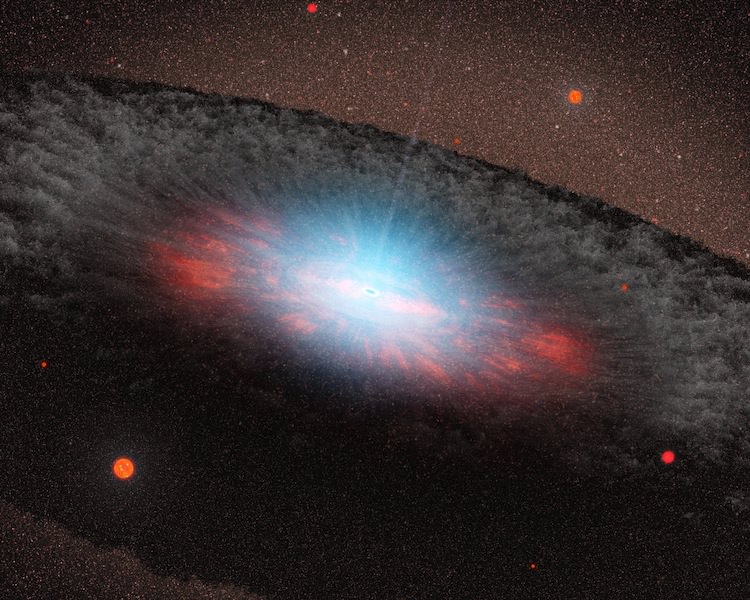

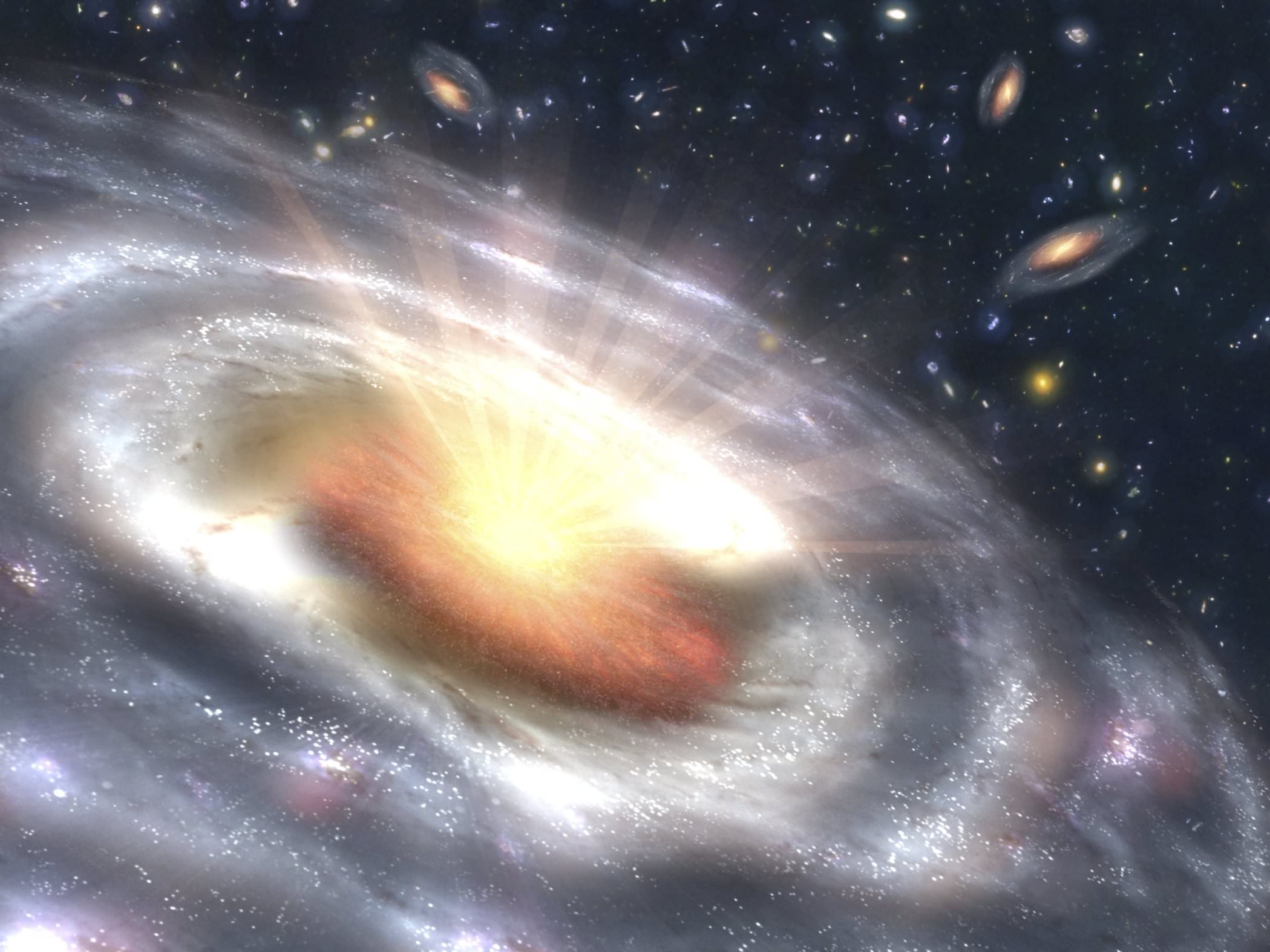

For those who saw the Cosmos episode on William Herschel describing telescopes as time machines, here is a clear example of that. By examining 140,000 objects called quasars (galaxies with an active black hole at their centers), astronomers have charted the expansion rate of the universe — not now, but 10.8 billion years ago.

This is the most precise measurement ever of the universe’s expansion rate at any point in time, the science teams said, with the calculation showing the universe was expanding by 1% every 44 million years at that time. (That figure is to 2% precision, the researchers added.)

“If we look back to the Universe when galaxies were three times closer together than they are today, we’d see that a pair of galaxies separated by a million light-years would be drifting apart at a speed of 68 kilometers per second as the Universe expands,” stated Andreu Font-Ribera of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, who led one of the two analyses.

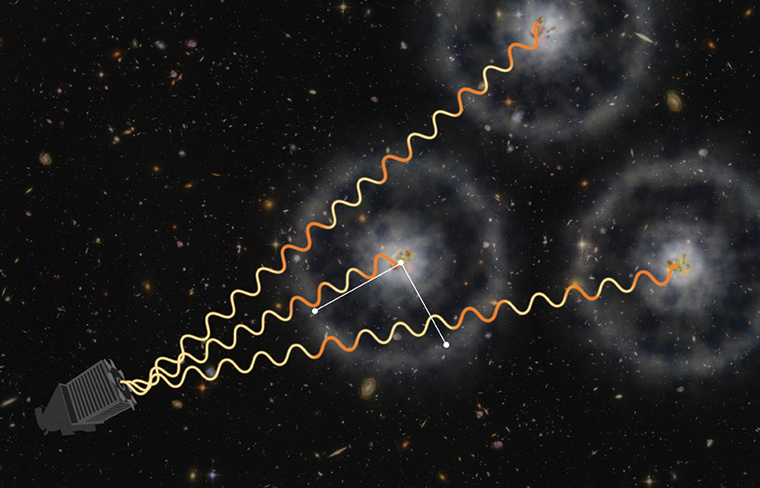

The researchers used a telescope called the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, a 2.5-meter telescope at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico. The discovery was made during Sloan’s Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey, or BOSS, whose aim has been to figure out the expansion and acceleration of the universe.

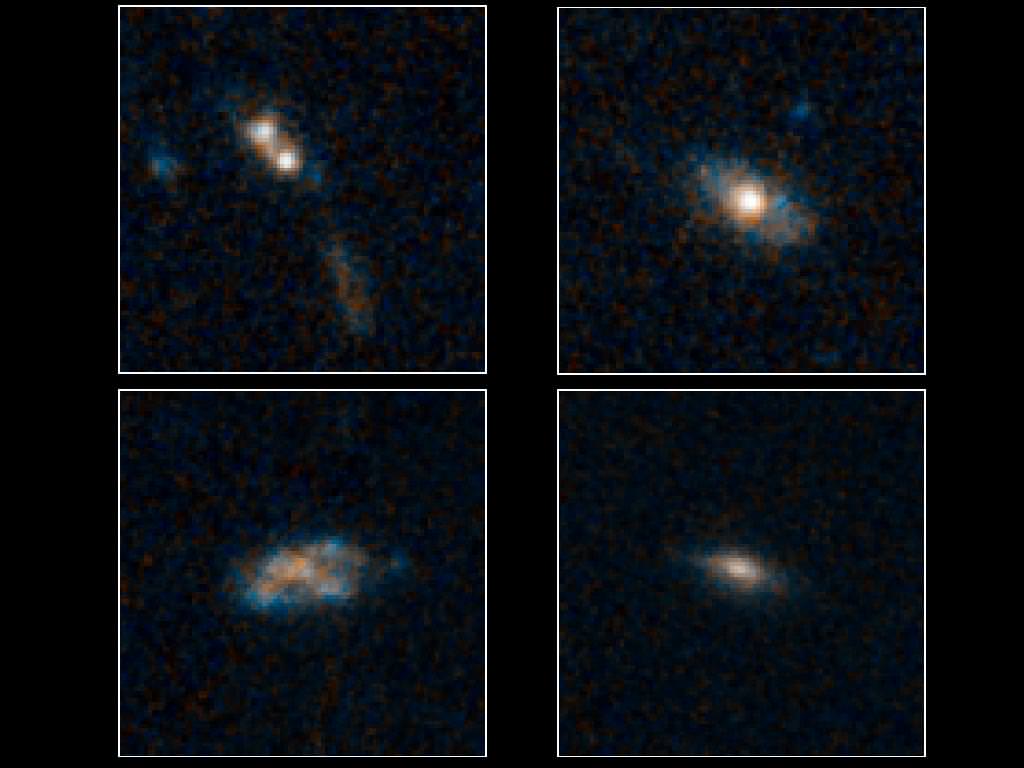

“BOSS determines the expansion rate at a given time in the Universe by measuring the size of baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO), a signature imprinted in the way matter is distributed, resulting from sound waves in the early Universe,” the Sloan Digital Sky Survey stated. “This imprint is visible in the distribution of galaxies, quasars, and intergalactic hydrogen throughout the cosmos.”

Font-Ribera and his collaborators examined how quasars are distributed compared to hydrogen gas to calculate distance. The other analysis, led by Timothée Delubac (Centre de Saclay, France), examined the hydrogen gas to see patterns and measure mass distribution.

You can read more about Font-Ribera’s team’s research in preprint version on Arxiv. Delubac’s research does not appear to be available online, but the title is “Baryon Acoustic Oscillations in the Ly-alpha forest of BOSS DR11 quasars” and it has been submitted to Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Source: Sloan Digital Sky Survey