In 1909 Robert Millikan devised an ingenious experiment to figure out the charge of an electron using a drop of oil. Let’s talk about this Nobel Prize winning experiment

Continue reading “Astronomy Cast Ep. 372: Millikan Oil Drop”

What Is A Wolf-Rayet Star?

Wolf-Rayet stars represent a final burst of activity before a huge star begins to die. These stars, which are at least 20 times more massive than the Sun, “live fast and die hard”, according to NASA.

Their endstate is more famous; it’s when they explode as supernova and seed the universe with cosmic elements that they get the most attention. But looking at how the star gets to that explosive stage is also important.

When you look at a star like the Sun, what you are seeing is a delicate equilibrium of the star’s gravity pulling stuff in, and nuclear fusion inside pushing pressure out. When the forces are about equal, you get a stable mass of fusing elements. For planets like ours lucky enough to live near a stable star, this period can go on for billions upon billions of years.

Being near a massive star is like playing with fire, however. They grow up quickly and thus die earlier in their lives than the Sun. And in the case of a Wolf-Rayet star, it’s run out of lighter elements to fuse inside its core. The Sun is happily churning hydrogen into helium, but Wolf-Rayets are ploughing through elements such as oxygen to try to keep equilibrium.

Because these elements have more atoms per unit, this creates more energy — specifically, heat and radiation, NASA says. The star begins to blow out winds reaching 2.2 million to 5.4 million miles per hour (3.6 million to 9 million kilometers per hour). Over time, the winds strip away the outer layers of the Wolf-Rayet. This eliminates much of its mass, while at the same time freeing its elements to be used elsewhere in the Universe.

Eventually, the star runs out of elements to fuse (the process can go no further than iron). When the fusion stops, the pressure inside the star ceases and there’s nothing to stop gravity from pushing in. Big stars explode as supernova. Bigger ones see their gravity warped so much that not even light can escape, creating a black hole.

We still have a lot to learn about stellar evolution, but a few studies over the years have provided insights. In 2004, for example, NASA issued reassuring news saying these stars don’t “die alone.” Most of them have a stellar companion, according to Hubble Space Telescope observations.

While at first glance this appears as just a simple observation, cosmologists said that it could help us figure out how these stars get so big and bright. For example: Maybe the bigger star (the one that turns into a Wolf-Rayet) feeds off its companion over time, gathering mass until it becomes stupendously big. With more fuel, the big stars burn out faster. Other things the smaller star could influence could be the bigger star’s rotation or orbit.

Here’s a few other facts about Wolf-Rayets, courtesy of astronomer David Darling:

- Their names come from two French astronomers, Charles Wolf and Georges Rayet, who discovered the first known star of this kind in 1867.

- Wolf-Rayets come in two flavours: WN (emission lines of helium and nitrogen) and WC (carbon, oxygen and hydrogen).

- Stars like our Sun evolve into more massive red giants as they run out of hydrogen to burn in the core. When these stars begin to shed their outer layers, they behave somewhat similarly to Wolf-Rayets. So they’re called “Wolf-Rayet type stars”, although they’re not exactly the same thing.

We have written many articles about stars here on Universe Today. Here’s an article about a binary pair of Wolf-Rayet stars, and the good news that WR 104 won’t kill us all. We have recorded several episodes of Astronomy Cast about stars. Here are two that you might find helpful: Episode 12: Where Do Baby Stars Come From, and Episode 13: Where Do Stars Go When they Die?

The Science of Heat Transfer: What Is Conduction?

Heat is an interesting form of energy. Not only does it sustain life, make us comfortable and help us prepare our food, but understanding its properties is key to many fields of scientific research. For example, knowing how heat is transferred and the degree to which different materials can exchange thermal energy governs everything from building heaters and understanding seasonal change to sending ships into space.

Heat can only be transferred through three means: conduction, convection and radiation. Of these, conduction is perhaps the most common, and occurs regularly in nature. In short, it is the transfer of heat through physical contact. It occurs when you press your hand onto a window pane, when you place a pot of water on an active element, and when you place an iron in the fire.

This transfer occurs at the molecular level — from one body to another — when heat energy is absorbed by a surface and causes the molecules of that surface to move more quickly. In the process, they bump into their neighbors and transfer the energy to them, a process which continues as long as heat is still being added.

The process of heat conduction depends on four basic factors: the temperature gradient, the cross section of the materials involved, their path length, and the properties of those materials.

A temperature gradient is a physical quantity that describes in which direction and at what rate the temperature changes in a specific location. Temperature always flows from the hottest to coldest source, due to the fact that cold is nothing but the absence of heat energy. This transfer between bodies continues until the temperature difference decays, and a state known as thermal equilibrium occurs.

Cross-section and path length are also important factors. The greater the size of the material involved in the transfer, the more heat is needed to warm it. Also, the more surface area that is exposed to open air, the greater likelihood for heat loss. So shorter objects with a smaller cross-section are the best means of minimizing the loss of heat energy.

Last, but certainly not least, is the physical properties of the materials involved. Basically, when it comes to conducting heat, not all substances are created equal. Metals and stone are considered good conductors since they can speedily transfer heat, whereas materials like wood, paper, air, and cloth are poor conductors of heat.

These conductive properties are rated based on a “coefficient” which is measured relative to silver. In this respect, silver has a coefficient of heat conduction of 100, whereas other materials are ranked lower. These include copper (92), iron (11), water (0.12), and wood (0.03). At the opposite end of the spectrum is a perfect vacuum, which is incapable of conducting heat, and is therefore ranked at zero.

Materials that are poor conductors of heat are called insulators. Air, which has a conduction coefficient of .006, is an exceptional insulator because it is capable of being contained within an enclosed space. This is why artificial insulators make use of air compartments, such as double-pane glass windows which are used for cutting heating bills. Basically, they act as buffers against heat loss.

Feather, fur, and natural fibers are all examples of natural insulators. These are materials that allows birds, mammals and human beings to stay warm. Sea otters, for example, live in ocean waters that are often very cold and their luxuriously thick fur keeps them warm. Other sea mammals like sea lions, whales and penguins rely on thick layers of fat (aka. blubber) – a very poor conductor – to prevent heat loss through their skin.

This same logic is applied to insulating homes, buildings, and even spacecraft. In these cases, methods involve either trapped air pockets between walls, fiber-glass (which traps air within it) or high-density foam. Spacecraft are a special case, and use insulation in the form of foam, reinforced carbon composite material, and silica fiber tiles. All of these are poor conductors of heat, and therefore prevent heat from being lost in space and also prevent the extreme temperatures caused by atmospheric reentry from entering the crew cabin.

See this video demonstration of the heat tiles on the Space Shuttle:

The laws governing conduction of heat are very similar to Ohm’s Law, which governs electrical conduction. In this case, a good conductor is a material that allows electrical current (i.e. electrons) to pass through it without much trouble. An electric insulator, by contrast, is any material whose internal electric charges do not flow freely, and therefore make it very hard to conduct an electric current under the influence of an electric field.

In most cases, materials that are poor conductors of heat are also poor conductors of electricity. For instance, copper is good at conducting both heat and electricity, hence why copper wires are used so widely in the manufacture of electronics. Gold and silver are even better, and where price is not an issue, these materials are used in the construction of electrical circuits as well.

And when one is looking to “ground” a charge (i.e. neutralize it), they send it through a physical connection to the Earth, where the charge is lost. This is common with electrical circuits where exposed metal is a factor, ensuring that people who accidentally come into contact are not electrocuted.

Insulating materials, such as rubber on the soles of shoes, is worn to ensure that people working with sensitive materials or around electrical sources are protected from electrical charges. Other insulating materials like glass, polymers, or porcelain are commonly used on power lines and high-voltage power transmitters to keep power flowing to the circuits (and nothing else!)

In short, conduction comes down to the transfer of heat or the transfer of an electrical charge. Both happen as a result of a substance’s ability to allow molecules to transfer energy across them.

We have written many articles about conduction for Universe Today. Check out this article on the first law of thermodynamics, or this one on static electricity.

If you’d like more info on the conduction, check out BBC’s article about Heat Transfer, and here’s a link to The Physics Hypertextbook.

We’ve also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast about Magnetism – Episode 42: Magnetism Everywhere.

First Orion Flight Will Assess Radiation Risk As NASA Thinks About Human Mars Missions

If you wanna get humans to Mars, there are so many technical hurdles in the way that it will take a lot of hard work. How to help people survive for months on a hostile surface, especially one that is bathed on radiation? And how will we keep those people safe on the long journey there and back?

NASA is greatly concerned about the radiation risk, and is asking the public for help in a new challenge as the agency measures radiation with the forthcoming uncrewed Orion test flight in December. There’s $12,000 up for grabs across at least a few awards, providing you get your ideas into the agency by Dec. 12.

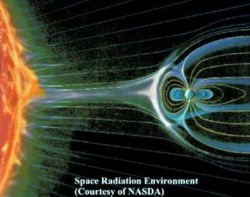

“One of the major human health issues facing future space travelers venturing beyond low-Earth orbit is the hazardous effects of galactic cosmic rays (GCRs),” NASA wrote in a press release.

“Exposure to GCRs, immensely high-energy radiation that mainly originates outside the solar system, now limits mission duration to about 150 days while a mission to Mars would take approximately 500 days. These charged particles permeate the universe, and exposure to them is inevitable during space exploration.”

Orion in orbit in this artists concept. Credit: NASA

Here’s an interesting twist, too — more data will come through the Orion test flight as the next-generation spacecraft aims for a flight 3,600 miles (5,800 kilometers) above Earth’s surface. That’s so high that the vehicle will go inside a high-radiation environment called the Van Allen Belts, which only the Apollo astronauts passed through in the 1960s and 1970s en route to the Moon.

While a flight to Mars will also just graze this area briefly, scientists say the high-radiation environment will give them a sense of how Orion (and future spacecraft) perform in this kind of a zone. So the spacecraft will carry sensors on board to measure overall radiation levels as well as “hot spots” within the vehicle.

You can find out more information about the challenge, and participation details, at this link.

Source: NASA

How Quickly Do Black Holes Form?

A star can burn its hydrogen for millions or even billions of years. But when the party’s over, black holes form in an instant. How long does it all take to happen.

Uh-oh! You’re right next to a black hole that’s starting to form.

In the J.J. Abrams Star Trek Universe, this ended up being a huge inconvenience for Spock as he tried to evade a ticked off lumpy forehead Romulan who’d made plenty of questionable life choices, drunk on Romulan ale and living above a tattoo parlor.

So, if you were piloting Spock’s ship towards the singularity, do you have any hope of escaping before it gets to full power? Think quickly now. This not only has implications for science, but most importantly, for the entire Star Trek reboot! Or you know, we can just create a brand new timeline. Everybody’s doing it. Retcon, ftw.

Most black holes come to be after a huge star explodes into a supernova. Usually, the force of gravity in a huge star is balanced by its radiation – the engine inside that sends out energy into space. But when the star runs out of fuel to burn, gravity quickly takes over and the star collapses. But how quickly? Ready your warp engines and hope for the best.

Here’s the bad news – there’s not much hope for Spock or his ship. A star’s collapse happens in an instant, and the star’s volume gets smaller and smaller. Your escape velocity – the energy you need to escape the star – will quickly exceed the speed of light.

You could argue there’s a moment in time where you could escape. This isn’t quite the spot to argue about Vulcan physiology, but I assume their reaction time is close to humans. It would happen faster than you could react, and you’d be boned.

But look at the bright side – maybe you’d get to discover a whole new universe. Unless of course Black holes just kill you, and aren’t sweet magical portals for you and your space dragon which you can name Spock, in honor of your Vulcan friend who couldn’t outrun a black hole.

Here we’ve been talking about what happens if a black hole suddenly appears beside you. The good news is, supernovae can be predicted. Not very precisely, but astronomers can say which stars are nearing the end of their lives.

Here’s an example. In the constellation Orion, Betelgeuse the bright star on the right shoulder, is expected to go supernova sometime in the next few hundred thousand years.

That’s plenty of time to get out of the way.

So: black holes are dangerous for your health, but at least there’s lots of time to move out of the way if one looks threatening. Just don’t go exploring too close!

If you were to fall through a black hole, what do you think would happen? Naw, just kidding, we all know you’d die. Why don’t you tell us what your favorite black hole sci fi story is in the comments below!

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!

What is Nothing?

Is there any place in the Universe where there’s truly nothing? Consider the gaps between stars and galaxies? Or the gaps between atoms? What are the properties of nothing?

I want you to take a second and think about nothing. Close your eyes. Picture it in your mind. Focus. Fooooocus. On nothing….It’s pretty hard, isn’t it? Especially when I keep nattering at you.

Instead, let’s just consider the vast spaces between stars and galaxies, or the gaps between atoms and other microscopic particles. When we talk about nothing in the vast reaches between of space, it’s not actually, technically nothing. Got that? It’s not nothing. There’s… something there.

Even in the gulfs of intergalactic space, there are hundreds or thousands of particles in every cubic meter. But even if you could rent MegaMaid from a Dark Helmet surplus store, and vacuum up those particles, there would still be wavelengths of radiation, stretching across vast distances of space.

There’s the inevitable reach of gravity stretching across the entire Universe. There’s the weak magnetic field from a distant quasar. It’s infinitesimally weak, but it’s not nothing. It’s still something.

Philosophers, and some physicists, argue that *that* nothing isn’t the same as “real” nothing. Different physicists see different things as nothing, from nothing is classical vacuum, to the idea of nothing as undifferentiated potential.

Even if you could remove all the particles, shield against all electric and magnetic fields, your box would still contain gravity, because gravity can never be shielded or cancelled out. Gravity doesn’t go away, and it’s always attractive, so you can’t do anything to block it. In Newton’s physics that’s because it is a force, but in general relativity space and time *are* gravity.

So, imagine if you could remove all particles, energy, gravity… everything from a system. You’d be left with a true vacuum. Even at its lowest energy level, there are fluctuations in the quantum vacuum of the Universe. There are quantum particles popping into and out of existence throughout the Universe. There’s nothing, then pop, something, and then the particles collide and you’re left with nothing again. And so, even if you could remove everything from the Universe, you’d still be left with these quantum fluctuations embedded in spacetime.

There are physicists like Lawrence Krauss that argue the “universe from nothing”, really meaning “the universe from a potentiality”. Which comes down to if you add all the mass and energy in the universe, all the gravitational curvature, everything… it looks like it all sums up to zero. So it is possible that the universe really did come from nothing. And if that’s the case, then “nothing” is everything we see around us, and “everything” is nothing.

What do you think? How do you wrap your head around the idea of nothing? Tell us in the comments below. And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!

How Many Ways Can the Sun Kill You?

The Sun has a Swiss army knife of ways it can do you in, from radiation to solar flares. And when it dies, it’s taking you with it. What are the various ways the Sun can do you in?

There’s a terrifying ball of fire a short 150 million km away. Which, in galactic terms, is right on our doorstep. This super-heated ball of plasma-y death, has temperatures and pressures so high that atoms of hydrogen are crushed into helium.

We’ve told ourselves we’re a safe distance away, and generally understate the dangers of being gravitationally bound to a massive ongoing nuclear explosion which is catastrophically larger than anything we’ve ever managed to create here on Earth. We take its warmth and life-giving light for granted, and barely give it a second thought as we sunbathe, or laugh gregariously while frying eggs on sidewalks on days when it’s scorchingly hot out.

Have we been lulled into a false sense of security by an ancient and secret society of bananas crazy sun cultists? Instead of worshiping the giant BBQ death ball, should we be cowering in fear, waiting for the next great solar flare? So, how dangerous is that thing? What are all the ways the Sun could do us in? And how many of them does my insurance cover?

First, in 4.5 billion years nothing has managed to destroy our planet. In fact, life itself has existed for almost Earth’s entire history, and nothing has scoured the planet clear of all forms of life. So, don’t worry the most reasonable risk we face from the Sun in our lifetimes is from a solar flare – a sudden blast of brightness on the surface of the Sun.

These occur when the Sun’s magnetic field lines snap and reconfigure, releasing an enormous amount of energy. It’s the equivalent of hundreds of billions of tonnes of TNT and if we’re staring down the barrel of this blast, it’ll fire a stream of high energy particles right up our nose.

Fortunately, the Earth has evolved in a highly radioactive environment. We’re blasted by radiation from the Sun all the time. The Earth’s magnetic field lines channel the particles towards the poles, which is why we get to see the beautiful auroral displays.

We’re at little risk from flares from the Sun, but our technology isn’t so lucky. The increase of geomagnetic activity in our vicinity can overload electrical grids and take satellites offline. The most powerful geomagnetic storm in history, known as the Carrington Event in 1859, generated auroras as far south as Cuba. It didn’t cause any damage then, but it would cause a lot of damage to our fragile technology today.

For those of you now resting comfortably I say… Not so fast. This episode isn’t over yet. Our Sun is heating up, and its energy output is increasing.

As it uses up the hydrogen in its core, this region of the Sun contracts a little, and the Sun increases in temperature to balance things out. Over the next few hundred million years, temperatures on Earth will rise and rise. Within a billion years, the surface of the planet will be an inhospitable oven.

Eventually the oceans will boil and the hydrogen will be blown out of the atmosphere by the Sun’s solar wind. Even though the Sun will remain in its main sequence phase for another 4 billion years after that, any life will need to be living underground.

Of course, as we’ve discussed in previous episodes, the Sun’s final act of destruction will happen when it runs out of hydrogen fuel in its core. The core will contract and the Sun will puff up into a red giant, consuming the orbits of Mercury, Venus and possibly the Earth. And even if it doesn’t consume the Earth, it’ll hit our planet with so much heat and radiation that it’ll finally get around to scouring any life off the surface.

So, like your fanatical sun cultist friends. Don’t worry about the Sun. It might make sense to keep some spare batteries around for the times when solar flares knock out the lights for a few days, but the Sun is remarkably safe and stable. We’ve got billions of years of warm light and heat from our star. But after that, it might make sense to shop for a new home.

So what do you think? Where do you think we should move when the temperature of the Sun heats up?

Student Designed Radiation Experiment Chosen to Soar aboard Orion EFT-1 Test Flight In Dec. 2014

When NASA’s next generation human spaceflight vehicle Orion blasts off on its maiden unmanned test flight later this year, a radiation experiment designed by top American high school students will soar along and play a key role in investigating how best to safeguard the health of America’s future astronauts as they venture farther into deep space than ever before – past the Moon to Asteroids, Mars and Beyond!

The student designed radiation experiment was the centerpiece of a year-long Exploration Design Challenge (EDC) competition sponsored by NASA, Orion prime contractor Lockheed Martin and the National Institute of Aerospace, and was open to high school teams across the US.

The winning experiment design came from a five-member team of High School students from the Governor’s School for Science and Technology in Hampton, Va. and was announced by NASA Administrator Charles Bolden at the opening of the 2014 U.S.A Science and Engineering Festival held in Washington, DC on April 25.

NASA’s Administrator, Charles Bolden (left), President/CEO of Lockheed Martin, Marillyn Hewson (right), and astronaut Rex Walheim (back row) pose for a group photo with the winning high school team in the Exploration Design Challenge. Team ARES from the Governors School for Science and Technology in Hampton, Va. won the challenge with their radiation shield design, which will be built and flown aboard the Orion/EFT-1. Credit: NASA/Aubrey Gemignani

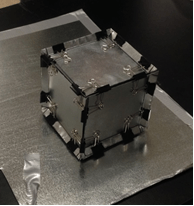

The goal of the EDC competition was to build and test designs for shields to minimize radiation exposure and damaging human health effects inside NASA’s new Orion spacecraft slated to launch into orbit during the Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1) pathfinding mission in December 2014. See experiment design photo herein.

During the EFT-1 flight, Orion will fly through the dense radiation field that surrounds the Earth in a protective shell of electrically charged ions – known as the Van Allen Belt – that begins 600 miles above Earth.

No humans have flown through the Van Allen Belt in more than 40 years since the Apollo era.

Team ARES from Hampton VA was chosen from a group of five finalist teams announced in March 2014.

“This is a great day for Team ARES – you have done a remarkable job,” said NASA Administrator Bolden.

“I really want to congratulate all of our finalists. You are outstanding examples of the power of American innovation. Your passion for discovery and the creative ideas you have brought forward have made us think and have helped us take a fresh look at a very challenging problem on our path to Mars.”

Since Orion EFT-1 will climb to an altitude of some 3,600 miles, the mission offers scientists the opportunity to understand how to mitigate the level of radiation exposure experienced by the astronaut crews who will be propelled to deep space destinations beginning at the end of this decade.

The student teams used a simulation tool named OLTARIS, the On- Line Tool for the Assessment of Radiation in Space, used by NASA scientists and engineers to study the effects of space radiation on shielding materials, electronics, and biological systems.

Working with mentors from NASA and Lockheed Martin, each team built prototypes and used the OLTARIS program to calculate how effective their designs – using several materials at varying thicknesses – were at shielding against radiation in the lower Van Allen belt.

“The experiment is a Tesseract Design—slightly less structurally sound than a sphere, as the stresses are located away from the cube on the phalanges. The materials and the distribution of the materials inside the tesseract were determined through research and simulation using the OLTARIS program,” Lockheed Martin spokeswoman Allison Rakes told me.

The students conducted research to determine which materials were most effective at radiation shielding to protect a dosimeter housed inside – an instrument used for measuring radiation exposure.

“The final material choices and thicknesses are (from outermost to innermost): Tantalum (.0762 cm/ .030 in), Tin (.1016 cm/ .040 in), Zirconium (.0762 cm/ .030 in), Aluminum (.0762 cm/ .030 in), and Polyethylene (9.398 cm/ 3.70 in),” according to Rakes.

At the conclusion of the EFT-1 flight, the students will use the measurement to determine how well their design protected the dosimeter.

But first Team ARES needs to get their winning proposal ready for flight. They will work with a NASA and Lockheed Martin spacecraft integration team to have the experimental design approved, assembled and installed into Orion’s crew module.

All the students hard work will pay off this December when Lockheed Martin hosts Team ARES at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to witness the liftoff of their important experiment inside Orion atop the mammoth triple barreled Delta IV Heavy booster.

46 teams from across the country submitted engineering experiment proposals to the EDC aimed at stimulating students to work on a science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) project that tackles one of the most significant dangers of human space flight — radiation exposure.

“The Exploration Design Challenge has already reached 127,000 students worldwide – engaging them in real-world engineering challenges and igniting their imaginations about the endless possibilities of space discovery,” said Lockheed Martin Chairman, President and CEO Marillyn Hewson.

The two-orbit, four- hour EFT-1 flight will lift the Orion spacecraft and its attached second stage to an orbital altitude of 3,600 miles, about 15 times higher than the International Space Station (ISS) – and farther than any human spacecraft has journeyed in 40 years.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Orion, Orbital Sciences, SpaceX, commercial space, LADEE, Curiosity, Mars rover, MAVEN, MOM and more planetary and human spaceflight news.

What’s The Fastest Way To Die In Space?

Space is a hostile environment for human beings. No part of it will permit you to survive longer than a minute. But what’s the fastest way to die in space?

Just in case you were planning to jump out into the vacuum of space without a spacesuit, I urge you to reconsider. There’s nothing but painful suffocation and death. Do not do it.

You probably wouldn’t be here if you weren’t wondering, just how lethal is space? What are all the ways space is trying to kill you? Space has a Swiss army knife of methods to do you in. You won’t be surprised to learn that classic sci-fi usually had it wrong. If you jumped out into the cold deep void without a protective suit, you wouldn’t pop like a giant pressurized juicy meat pimple. Your blood doesn’t boil, and you don’t flash freeze.

The good news is even though there is a pressure difference, human skin is strong enough to keep your body together. The bad news is you just plain old asphyxiate, almost instantaneously. The human body has about 15 seconds of usable oxygen in the blood. Once you run through that oxygen, you’ll take a quick space nap and then die a few minutes later.

On Earth, you can hold your breath for a few minutes but this gets much harder in space, as the low pressure forces the air out of your lungs. In fact, it would probably be wise to breathe every last bit of air out before you stepped out, since it’s coming out violently, one way or another.

Here’s the amazing thing. If you jumped out into space and could get back into a pressurized environment within a minute or so, you probably wouldn’t suffer any permanent damage, aside from a little bruising, some hypothermia and a really nasty sunburn. Stay out for any longer, though, and the damage will get worse. Beyond a few minutes and you’ll be done.Which is just fine, as you weren’t planning on going out into space without a spacesuit anyway.

Unfortunately, even tucked safely in your spacecraft, there are tremendous risks to being away from the comfort of Earth. You’ve got to be worried about radiation. Once a spacecraft leaves the protection of the Earth’s magnetic field, it’s exposed to the high levels constantly streaming through space. A trip from Earth to Mars and back again might increase your overall risk developing a fatal cancer by about 5%, and that’s a risk most astronauts are willing to take. But there are solar storms blasting out from the Sun that could deliver a lethal dose of radiation in just a few hours. Astronauts would need a safe, radiation-shielded location during these solar storms or they’d expire from acute radiation poisoning.

There are many, many other risks from traveling in space. Fire is one of the worst, failure of your oxygen system, access to clean water and food become an obvious problem. Even things we usually don’t think about, like mold building up in the damp environment of a spaceship becomes a problem.

Survive all these immediate hazards, just like here on Earth, and the long term hazards will get you. We have no idea if it’s even possible for the human body to exist in microgravity for longer than a few years. Your bones dissolve, your muscles waste away, and there might be other consequences.

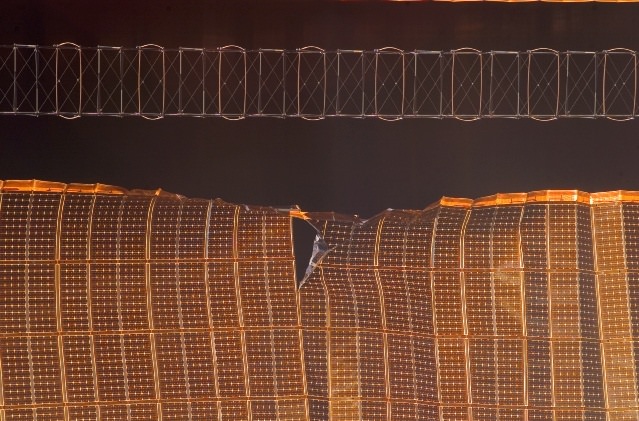

So far, nobody is willing to run the experiment long enough to find out. And finally, the fastest way space can kill you is likely impact with debris. Even though space is mostly empty, there’s all kinds of material whizzing around. Every spacecraft is pockmarked with micrometeorite impacts. There are holes punched through the International Space Station’s solar panels. These tiny pieces of rock can be traveling at 10 kilometers per second when they impact the spacecraft.

Spacecraft have layers of protection to absorb smaller particles, but there’s no way to prevent larger objects from causing catastrophic damage. If those layers weren’t there you’d be a short hop skip and a jump from becoming a heavily perforated spongebob spacepants. The solution? You just have to hope they never hit.

There certainly a many ways to quickly die in space, but what’s really amazing to me is how we can actually overcome many of these risks, certainly long enough to reach other worlds in the Solar System. Traveling in space is dangerous and difficult, but the exciting thing is it’s still possible. And one day, we’ll do it.

So, even knowing the risks, would you travel in space?

How Fast Do Black Holes Spin?

There is nothing in the Universe more awe inspiring or mysterious than a black hole. Because of their massive gravity and ability to absorb even light, they defy our attempts to understand them. All their secrets hide behind the veil of the event horizon.

What do they look like? We don’t know. They absorb all the radiation they emit. How big are they? Do they have a size, or could they be infinitely dense? We just don’t know. But there are a few things we can know. Like how massive they are, and how fast they’re spinning.

Wait, what? Spinning?

Consider the massive star that came before the black hole. It was formed from a solar nebula, gaining its rotation by averaging out the momentum of all the individual particles in the cloud. As mutual gravity pulled the star together, through the conservation of angular momentum it rotated more rapidly. When a star becomes a black hole, it still has all that mass, but now compressed down into an infinitesimally smaller space. And to conserve that angular momentum, the black hole’s rate of rotation speeds up… a lot.The entire history of everything the black hole ever consumed, averaged down to a single number: the spin rate.

If the black hole could shrink down to an infinitely small size, you would think that the spin rate might increase to infinity too. But black holes have a speed limit.

“There is a speed limit to the spin of a black hole. It’s sort of set by the faster a black hole spins, the smaller is its event horizon.”

That’s Dr. Mark Morris, a professor of astronomy at UCLA. He has devoted much of his time to researching the mysteries of black holes.

“There is this region, called the ergosphere between the event horizon and another boundary, outside. The ergosphere is a very interesting region outside the event horizon in which a variety of interesting effects can occur.”

Imagine the event horizon of a black hole as a sphere in space, and then surrounding this black hole is the ergosphere. The faster the black hole spins, the more this ergosphere flattens out.

“The speed limit is set by the event horizon, eventually, at a high enough spin, reaches the singularity. You can’t have what’s called a naked singularity. You can’t have a singularity exposed to the rest of the Universe. That would mean that the singularity itself could emit energy or light and somebody outside could actually see it. And that can’t happen. That’s the physical limitation of how fast it can spin. Physicists use units for angular momentum that are cast in terms of mass, which is a curious thing, and the speed limit can be described as the angular momentum equals the mass of the black hole, and that sets the speed limit.”

Just imagine. The black hole spins up to the point that it’s just about to reveal itself. But that’s impossible. The laws of physics won’t let it spin any faster. And here’s the amazing part. Astronomers have actually detected supermassive black holes spinning at the limits predicted by these theories.

One black hole, at the heart of galaxy NGC 1365 is turning at 84% the speed of light. It has reached the cosmic speed limit, and can’t spin any faster without revealing its singularity.

The Universe is a crazy place.