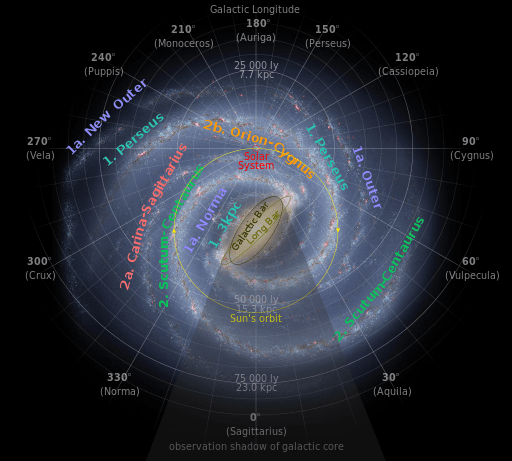

Given that our Solar System sits inside the Milky Way Galaxy, getting a clear picture of what it looks like as a whole can be quite tricky. In fact, it was not until 1852 that astronomer Stephen Alexander first postulated that the galaxy was spiral in shape. And since that time, numerous discoveries have come along that have altered how we picture it.

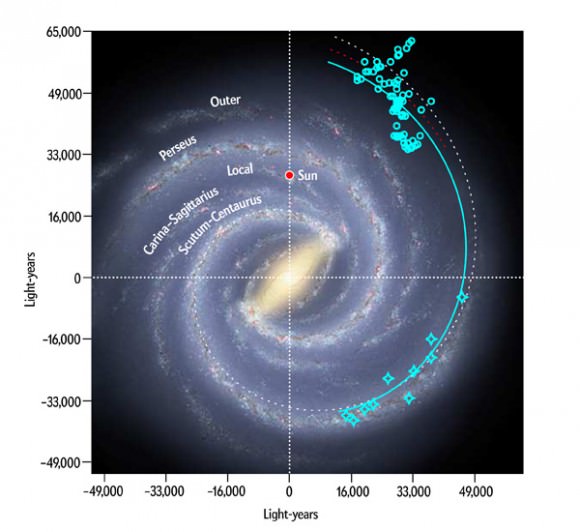

For decades astronomers have thought the Milky Way consists of four arms — made up of stars and clouds of star-forming gas — that extend outwards in a spiral fashion. Then in 2008, data from the Spitzer Space Telescope seemed to indicate that our Milky Way has just two arms, but a larger central bar. But now, according to a team of astronomers from China, one of our galaxy’s arms may stretch farther than previously thought, reaching all the way around the galaxy.

This arm is known as Scutum–Centaurus, which emanates from one end of the Milky Way bar, passes between us and Galactic Center, and extends to the other side of the galaxy. For many decades, it was believed that was where this arm terminated.

However, back in 2011, astronomers Thomas Dame and Patrick Thaddeus from the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics spotted what appeared to be an extension of this arm on the other side of the galaxy.

But according to astronomer Yan Sun and colleagues from the Purple Mountain Observatory in Nanjing, China, the Scutum–Centaurus Arm may extend even farther than that. Using a novel approach to study gas clouds located between 46,000 to 67,000 light-years beyond the center of our galaxy, they detected 48 new clouds of interstellar gas, as well as 24 previously-observed ones.

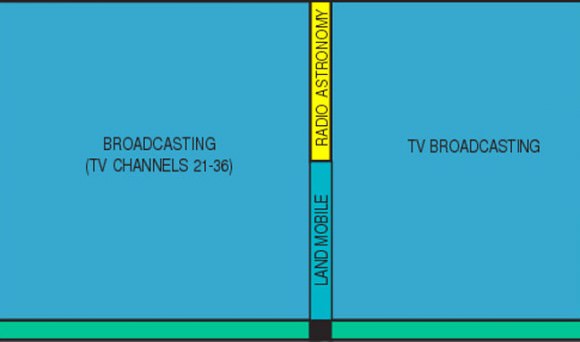

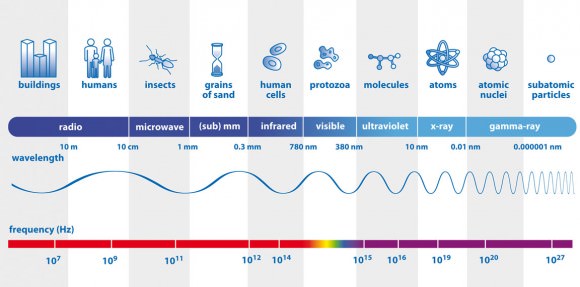

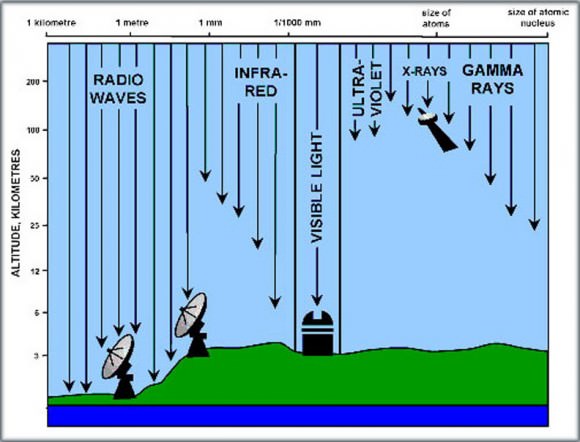

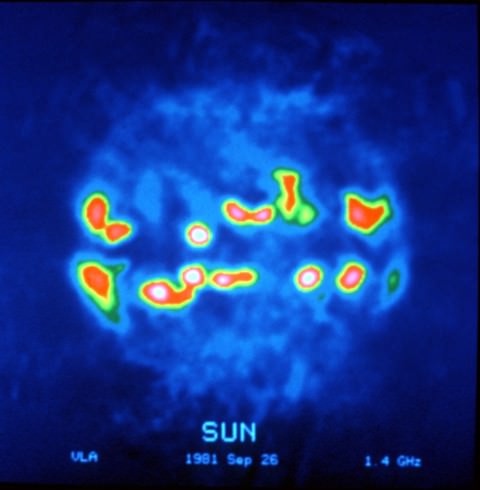

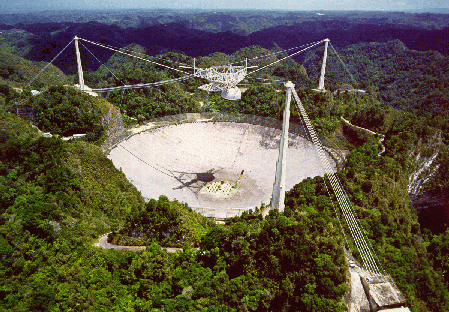

For the sake of their study, Sun and his colleagues relied on radio telescope data provided by the Milky Way Imaging Scroll Painting project, which scans interstellar dust clouds for radio waves emitted by carbon monoxide gas. Next to hydrogen, this gas is the most abundant element to be found in interstellar space – but is easier for radio telescopes to detect.

Combining this information with data obtained by the Canadian Galactic Plane Survey (which looks for hydrogen gas), they concluded that these 72 clouds line up along a spiral-arm segment that is 30,000 light-years in length. What’s more, they claim in their report that: “The new arm appears to be the extension of the distant arm recently discovered by Dame & Thaddeus (2011) as well as the Scutum-Centaurus Arm into the outer second quadrant.”

This would mean the arm is not only the single largest in our galaxy, but is also the only one to effectively reach 360° around the Milky Way. Such a find would be unprecedented given the fact that nothing of the sort has been observed with other spiral galaxies in our local universe.

Thomas Dame, one of the astronomers who discovered the possible extension of the Scutum-Centaurus Arm in 2011, was quoted by Scientific American as saying: “It’s rare. I bet that you would have to look through dozens of face-on spiral galaxy images to find one where you could convince yourself you could track one arm 360 degrees around.”

Naturally, the prospect presents some problems. For one, there is an apparent gap between the segment that Dame and Thaddeus discovered in 2011 and the start of the one discovered by the Chinese team – a 40,000 light-year gap to be exact. This could mean that the clouds that Sun and his colleagues discovered may not be part of the Scutum-Centaurus Arm after all, but an entirely new spiral-arm segment.

If this is true, than it would mean that our Galaxy has several “outer” arm segments. On the other hand, additional research may close that gap (so to speak) and prove that the Milky Way is as beautiful when seen afar as any of the spirals we often observe from the comfort of our own Solar System.

Further Reading: arXiv Astrophysics, The Astrophysical Letters