The exoplanet discoveries have been coming fast and furious this week, as astronomers announced a new set of curious worlds this past Monday at the ongoing American Astronomical Society’s 224th Meeting being held in Boston, Massachusetts.

Now, chalk up two more worlds for a famous red dwarf star in our own galactic neck of the woods. An international team of astronomers including five researchers from the Carnegie Institution announced the discovery this week of two exoplanets orbiting Kapteyn’s Star, about 13 light years distant. The discovery was made utilizing data from the HIRES spectrometer at the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, as well as the Planet Finding Spectrometer at the Magellan/Las Campanas Observatory and the European Southern Observatory’s La Silla facility, both located in Chile.

The Carnegie Institution astronomers involved in the discovery were Pamela Arriagada, Ian Thompson, Jeff Crane, Steve Shectman, and Paul Butler. The planets were discerned using radial velocity measurements, a planet-hunting technique which looks for tiny periodic changes in the motion of a star caused by the gravitational tugging of an unseen companion.

“That we can make such precise measurements of such subtle effects is a real technological marvel,” said Jeff Crane of the Carnegie Observatories.

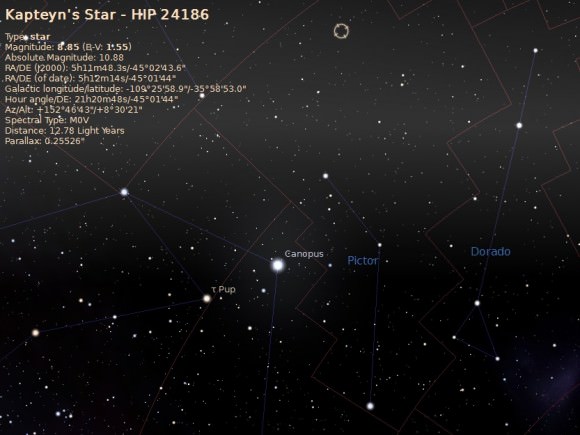

Kapteyn’s Star (pronounced Kapt-I-ne’s Star) was discovered by Dutch astronomer Jacobus Kapteyn during a photographic survey of the southern hemisphere sky in 1898. At the time, it had the highest proper motion of any star known at over 8” arc seconds a year — Kapteyn’s Star moves the diameter of a Full Moon across the sky every 225 years — and held this distinction until the discovery of Barnard’s Star in 1916. About a third the mass of our Sun, Kapteyn’s Star is an M-type red dwarf and is the closest halo star to our own solar system. Such stars are thought to be remnants of an ancient elliptical galaxy that was shredded and subsequently absorbed by our own Milky Way galaxy early on in its history. Its high relative velocity and retrograde orbit identify Kapteyn’s Star as a member of a remnant moving group of stars, the core of which may have been the glorious Omega Centauri star cluster.

The worlds of Kapteyn’s Star are proving to be curious in their own right as well.

“We were surprised to find planets orbiting Kapteyn’s Star,” said lead author Dr. Guillem Anglada-Escude, a former Carnegie post-doc now with the Queen Mary University at London. “Previous data showed some irregular motion, so we were looking for very short period planets when the new signals showed up loud and clear.”

It’s curious that nearby stars such as Kapteyn’s, Teegarden’s and Barnard’s star, though the site of many early controversial claims of exoplanets pre-1990’s, have never joined the ranks of known worlds which currently sits at 1,794 and counting until the discoveries of Kapteyn B and C. Kapteyn’s star is the 25th closest to our own and is located in the southern constellation Pictor. And if the name sounds familiar, that’s because it made our recent list of red dwarf stars for backyard telescopes. Shining at magnitude +8.9, Kapteyn’s star is visible from latitude 40 degrees north southward.

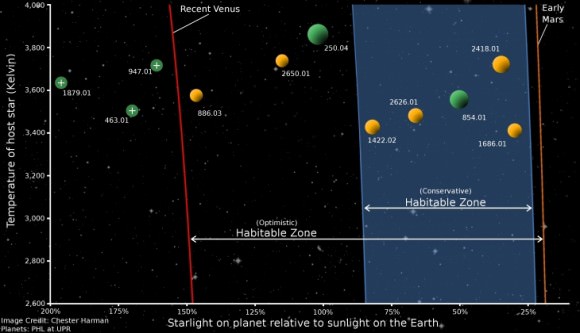

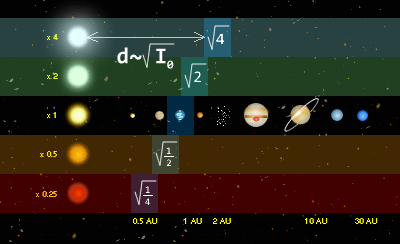

Kapteyn B and C are both suspected to be rocky super-Earths, at a minimum mass of 4.5 and 7 times that of Earth respectively. Kapteyn B orbits its primary once every 48.6 days at 0.168 A.U.s distant (about 40% of Mercury’s distance from our Sun) and Kapteyn C orbits once every 122 days at 0.3 A.U.s distant.

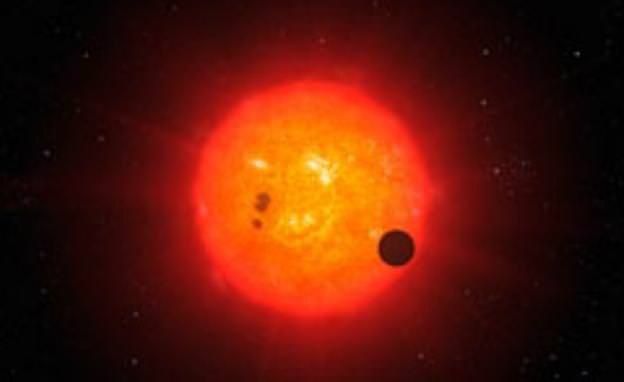

This is really intriguing, as Kapteyn B sits in the habitable zone of its host star. Though cooler than our Sun, the habitable zone of a red dwarf sits much closer in than what we enjoy in our own solar system. And although such worlds may have to contend with world-sterilizing flares, recent studies suggest that atmospheric convection coupled with tidal locking may allow for liquid water to exist on such worlds inside the “snow line”.

And add to this the fact that Kapteyn’s Star is estimated to be 11.5 billion years old, compared with the age of the universe at 13.7 billion years and our own Sun at 4.6 billion years. Miserly red dwarfs measure their future life spans in the trillions of years, far older than the present age of the universe.

“Finding a stable planetary system with a potentially habitable planet orbiting one of the very nearest stars in the sky is mind blowing,” said second author and Carnegie postdoctoral researcher Pamela Arriagada. “This is one more piece of evidence that nearly all stars have planets, and that potentially habitable planets in our galaxy are as common as grains of sand on the beach.”

Of course, radial velocity measurements only give you lower mass constraints, as we don’t know the inclination of the orbits of the planets with respect to our line of sight. Still, this exciting discovery could potentially rank as the oldest habitable super-Earth yet discovered, and would make a great follow-up target for the direct imaging efforts or the TESS space telescope set to launch in 2017.

“It does make you wonder what kind of life could have evolved on those planets over such a long time,” added Dr Anglada-Escude. And certainly, the worlds of Kapteyn’s Star have had a much longer span of time for evolution to have taken hold than Earth… an exciting prospect, indeed!

-Read author Alastair Reynolds’ short science fiction piece Sad Kapteyn accompanying this week’s announcement.