I love it when scientists discover something unusual in nature. They have no idea what it is, and then over decades of research, evidence builds, and scientists grow to understand what’s going on.

My favorite example? Quasars.

Astronomers first knew they had a mystery on their hands in the 1960s when they turned the first radio telescopes to the sky.

They detected the radio waves streaming off the Sun, the Milky Way and a few stars, but they also turned up bizarre objects they couldn’t explain. These objects were small and incredibly bright.

They named them quasi-stellar-objects or “quasars”, and then began to argue about what might be causing them. The first was found to be moving away at more than a third the speed of light.

But was it really?

What could do this?

Here’s where Astronomers got creative. Maybe quasars weren’t really that bright, and it was our understanding of the size and expansion of the Universe that was wrong. Or maybe we were seeing the results of a civilization, who had harnessed all stars in their galaxy into some kind of energy source.

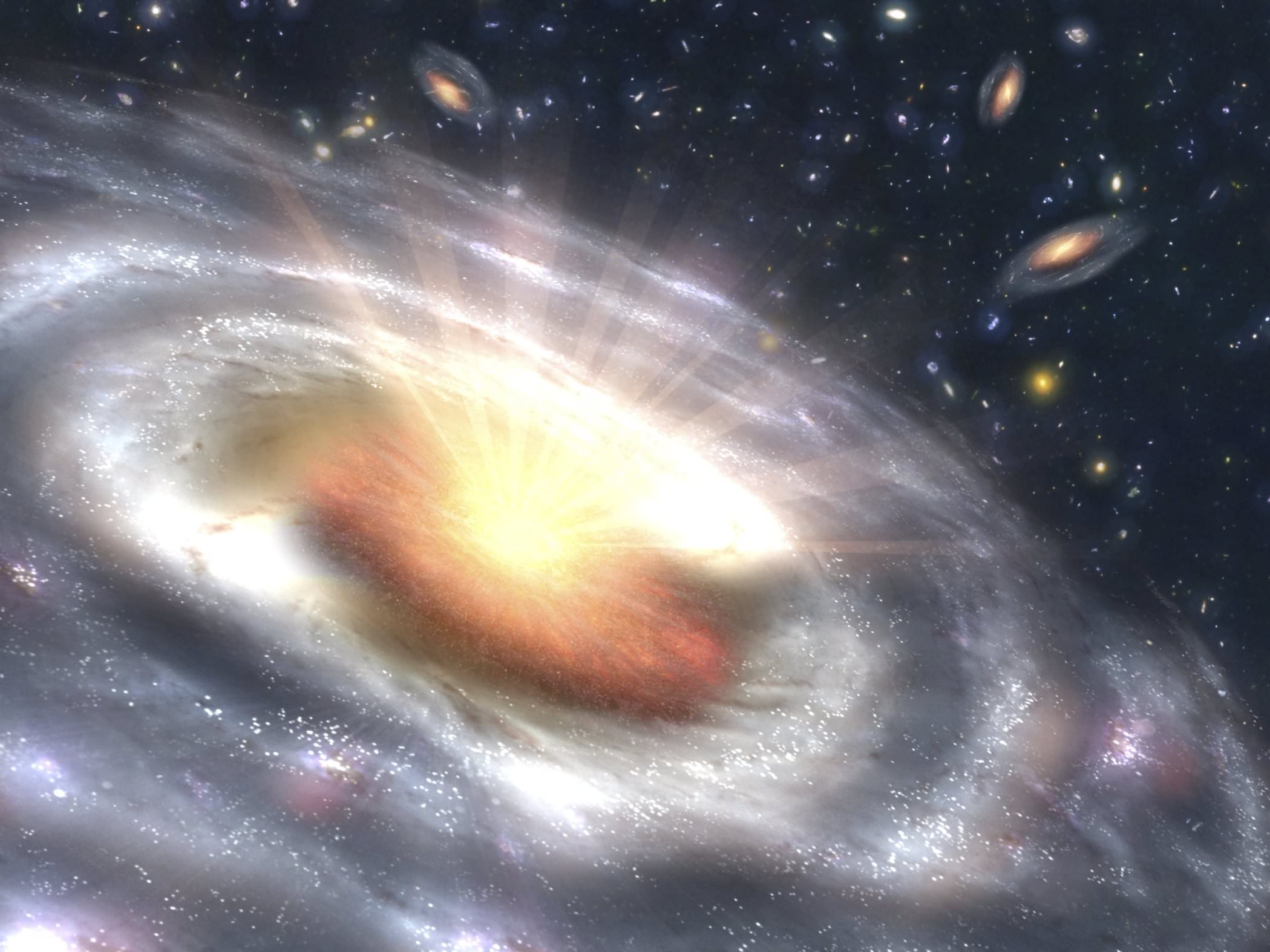

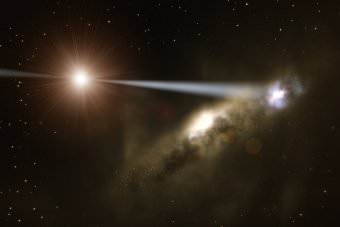

Then in the 1980s, astronomers started to agree on the active galaxy theory as the source of quasars. That, in fact, several different kinds of objects: quasars, blazars and radio galaxies were all the same thing, just seen from different angles. And that some mechanism was causing galaxies to blast out jets of radiation from their cores.

But what was that mechanism?

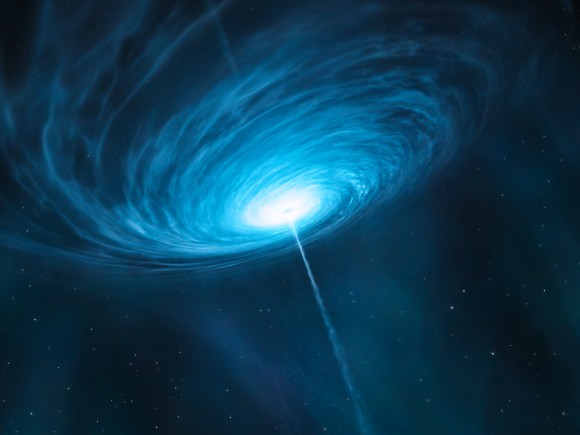

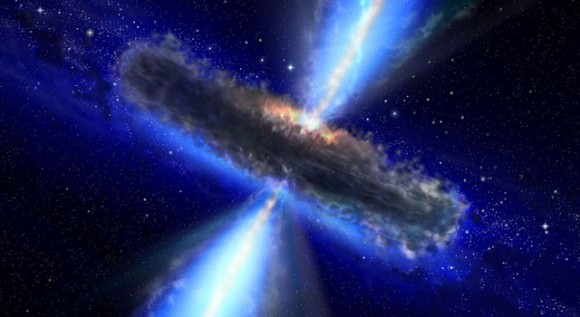

The magnetic environment around the black hole forms twin jets of material which flow out into space for millions of light-years. This is an AGN, an active galactic nucleus.

When the jets are perpendicular to our view, we see a radio galaxy. If they’re at an angle, we see a quasar. And when we’re staring right down the barrel of the jet, that’s a blazar. It’s the same object, seen from three different perspectives.

When the jets are perpendicular to our view, we see a radio galaxy. If they’re at an angle, we see a quasar. And when we’re staring right down the barrel of the jet, that’s a blazar. It’s the same object, seen from three different perspectives.

Supermassive black holes aren’t always feeding. If a black hole runs out of food, the jets run out of power and shut down. Right up until something else gets too close, and the whole system starts up again.

The Milky Way has a supermassive black hole at its center, and it’s all out of food. It doesn’t have an active galactic nucleus, and so, we don’t appear as a quasar to some distant galaxy.

We may have in the past, and may again in the future. In 10 billion years or so, when the Milky way collides with Andromeda, our supermassive black hole may roar to life as a quasar, consuming all this new material.

If you’d like more information on Quasars, check out NASA’s Discussion on Quasars, and here’s a link to NASA’s Ask an Astrophysicist Page about Quasars.

We’ve also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast all about Quasars Listen here, Episode 98: Quasars.

Sources: UT-Knoxville, NASA, Wikipedia