Move over Arianespace and United Launch Alliance. SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket is set for its maiden launch this November. The long-awaited Falcon Heavy should be able to outperform both the Ariane 5 and the ULA Delta-4 Heavy, at least in some respects.

The payload for the maiden voyage is uncertain so far. According to Gwynne Shotwell, SpaceX’s President and CEO, a number of companies have expressed interest in being on the first flight. Shotwell has also said that it might make more sense for SpaceX to completely own their first flight, without the pressure to keep a client happy. But a satellite payload for the first launch hasn’t been ruled out.

Delivering a payload into orbit is what the Falcon Heavy, and its competitors the Ariane5 and the ULA Delta-4 Heavy, are all about. Since one of the main competitive points of the Falcon Heavy is its ability to put larger payloads into geo-stationary orbits, accomplishing that feat on its first flight would be a great coming out party for the Falcon Heavy.

SpaceX has promised that it will make its first Falcon Heavy launch useful. They say that they will use the flight either to demonstrate to its commercial customers the rocket’s capability to deliver a payload to GTO, or to demonstrate to national security interests its ability to meet their needs.

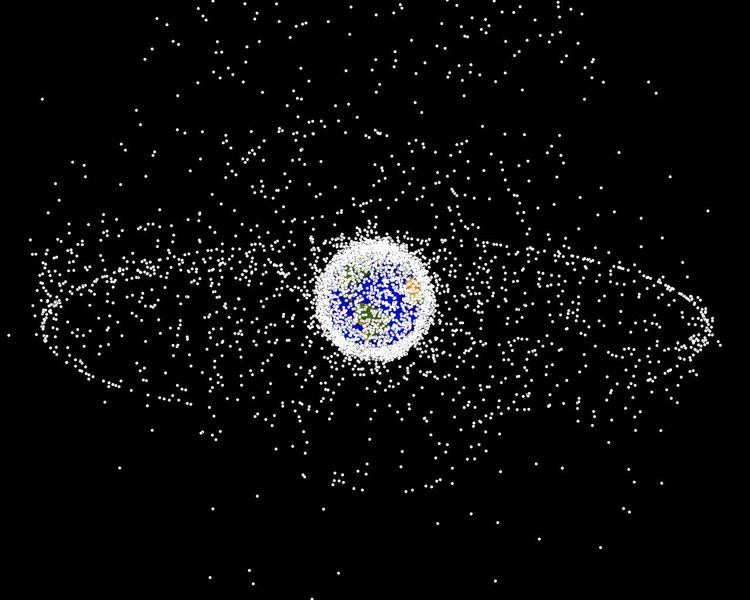

National security satellites require different capabilities from launch vehicles than do commercial communication satellites. Since these spacecraft are top secret, and are used to spy on communications, they need to be placed directly into their GTO, avoiding the lower-altitude transfer orbit of commercial satellites.

The payload for the first launch of the Falcon Heavy is not the only thing in question. There’s some question whether the November launch date can be achieved, since the Falcon Heavy has faced some delays in the past.

The inaugural flight for the big brother to the Falcon 9 was originally set for 2013, but several delays have kept bumping the date. One of the main reasons for this was the state of the Falcon 9. SpaceX was focussed on Falcon 9’s landing capabilities, and put increased manpower into that project, at the expense of the Falcon Heavy. But now that SpaceX has successfully landed the Falcon 9, the company seems poised to meet the November launch date for the Heavy.

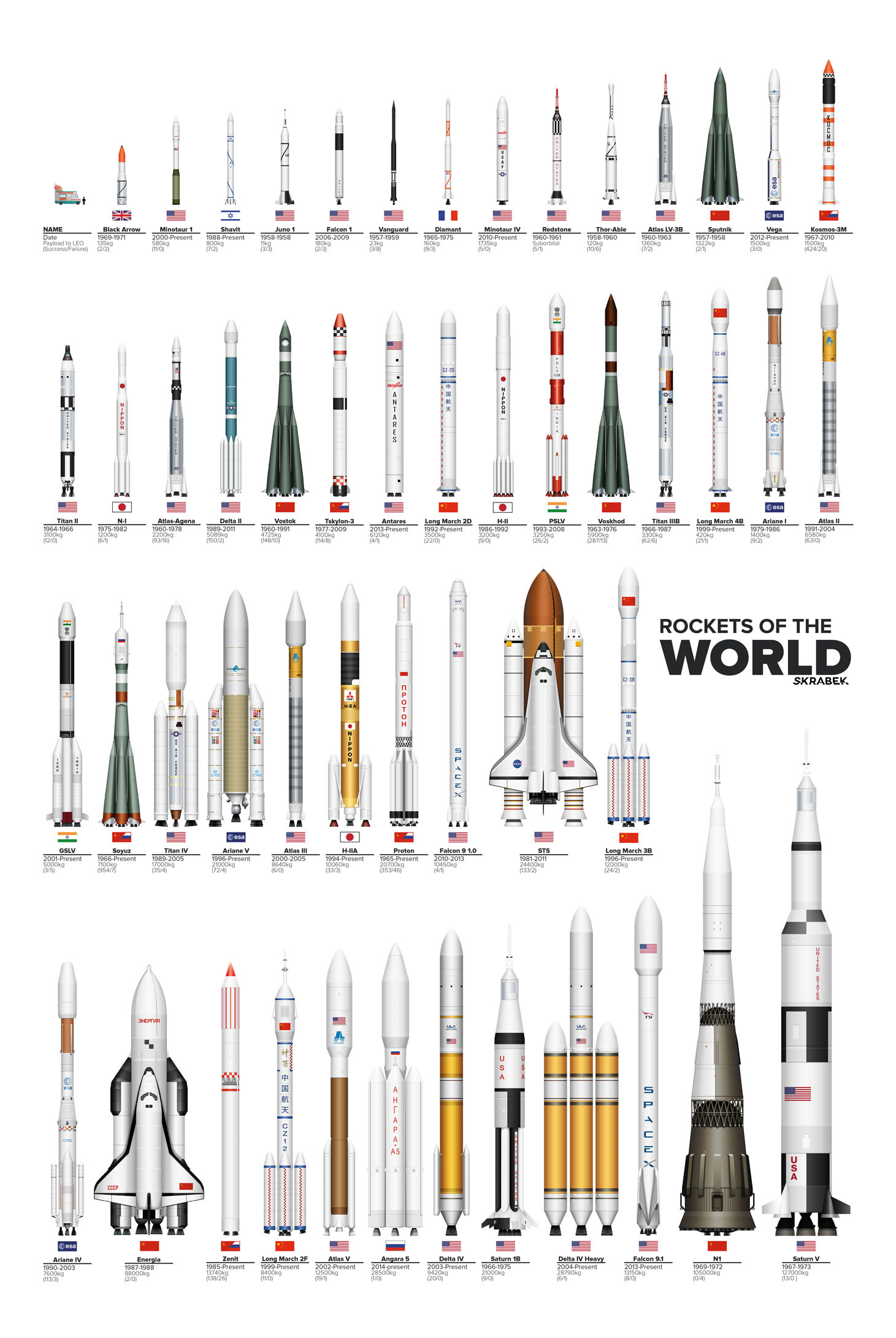

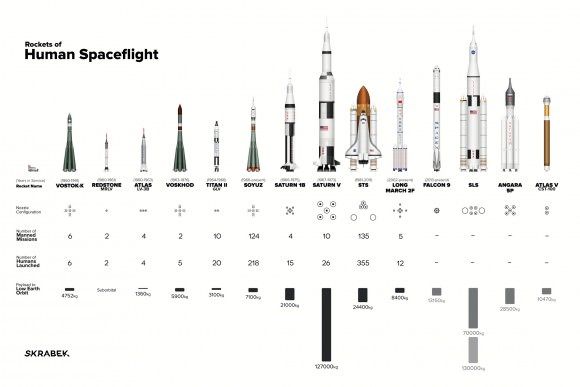

One of the main attractions to the Falcon Heavy is its ability to deliver larger payloads to geostationary orbit (GEO). This is the orbit occupied by communications and weather satellites. These types of satellites, and the companies that build and operate them, are an important customer base for SpaceX. SpaceX claims that the Falcon Heavy will be able to place payloads of 22,200 kg (48,940 lbs) to GEO. This trumps the Delta-4 Heavy (14,200 kg/31,350 lbs) and the Ariane5 (max. 10,500 kg/23,100 lbs.)

There’s a catch to these numbers, though. The Falcon Heavy will be able to deliver larger payloads to GEO, but it’ll do it at the expense of reusability. In order to recover the two side-boosters and central core stage for reuse, some fuel has to be held in reserve. Carrying that fuel and using it for recovery, rather than burning it to boost larger payloads, will reduce the payload for GEO to about 8,000 kg (17,637 lbs.) That’s significantly less than the Ariane 5, and the upcoming Ariane 6, which will both compete for customers with the Falcon Heavy.

The Falcon Heavy is essentially four Falcon 9 rockets configured together to create a larger rocket. Three Falcon 9 first stage boosters are combined to generate three times as much thrust at lift-off as a single Falcon 9. Since each Falcon 9 is actually made of 9 separate engines, the Falcon Heavy will actually have 27 separate engines powering its first stage. The second stage is another single Falcon 9 second-stage rocket, consisting of a single Merlin engine, which can be fired multiple times to place payloads in orbit.

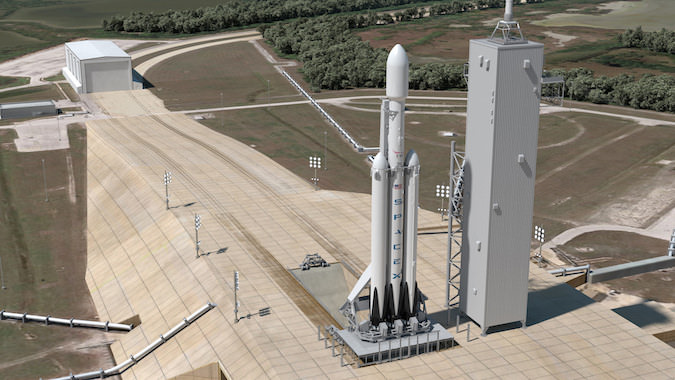

The three main boosters for the Falcon Heavy will all be built this summer, with construction of one already underway. Once complete, they will be transported from their construction facility in California to the testing facility in Texas. After that, they will be transported to Cape Canaveral.

Once at Cape Canaveral, the launch preparations will have all of the 27 engines in the first stage fired together in a hold-down firing, which will give SpaceX its first look at how all three main boosters operate together.

Eventually, if everything goes well, the Falcon Heavy will launch from Pad 39A at Cape Canaveral. Pad 39A is the site of the last Shuttle launches, and is now leased from NASA by SpaceX.

The Falcon Heavy will be the most powerful rocket around, once it’s operational. The versatility to deliver huge payloads to orbit, or to keep its costs down by recovering boosters, will make its first flight a huge achievement, whether or not it does deliver a satellite into orbit on its first launch.