The summer season means long days and short nights, as observers in the northern hemisphere must stay up later each evening waiting for darkness to fall. It also means that the best season to spot that orbital outpost of humanity—the International Space Station—is almost upon us. Get set for multiple passes a night for observers based in mid- to high- northern latitudes, starting this week.

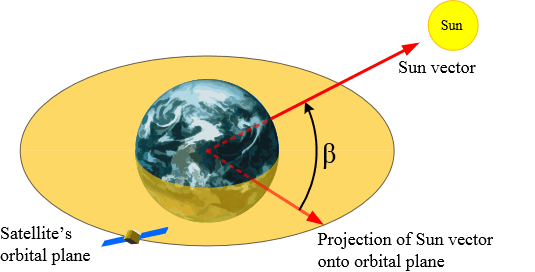

This phenomenon is the result of the station’s steep 52 degree inclination orbit. This means that near either solstice, the ISS spends a span of several days in permanent illumination. Multiple sightings favor the southern hemisphere around the December solstice and the northern hemisphere right around the upcoming June solstice.

Here’s a rundown of the ‘ISS all night’ season for 2015. The Sun rises on the ISS after a brief three minute orbital night on May 30th, 2015 at 16:43 UT, and doesn’t set again until five days later on June 4th at 4:57 UT over the central US. The ISS full illumination season comes a bit early this year—a few weeks before the June 21st northward solstice—and the next prospect at the end of July sees the Sun angle juuust shy of actually creating a second summer season.

NASA engineers refer to this period as high solar beta angle season. For a satellite in low Earth orbit, the beta angle describes the angle between its orbital plane and the relative direction of the Sun. Beta angle governs the satellite’s length of time in darkness and daylight. In the shuttle era, the Space Shuttle could not approach the ISS during these ‘beta cutout’ times, and the station generally goes into ‘rotisserie mode,’ as the ISS is rotated and its solar panels feathered to create alternating regions of artificial darkness in an effort to combat the continuous heating.

Why the 52 degree inclination orbit for the station? This allows the ISS to be accessible from launch sites worldwide in the spirit of international cooperation exemplified by the ISS. The station can and has been reached by cargo and human crews launching from Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the Baikonur Cosmodrome, the Tanegashima space port in Japan, and Kourou space center in French Guiana.

Our friend @OzoneVibe on Twitter suggested to us a few years back that a one night marathon session of ISS sightings be known as a FISSION, which stands for Four/Five ISS sightings In One Night. The prospective latitudes to carry out this feat run from 45 to 55 degrees north, which corresponds with northern Europe, the United Kingdom, and the region just north and south of the U.S./Canadian border.

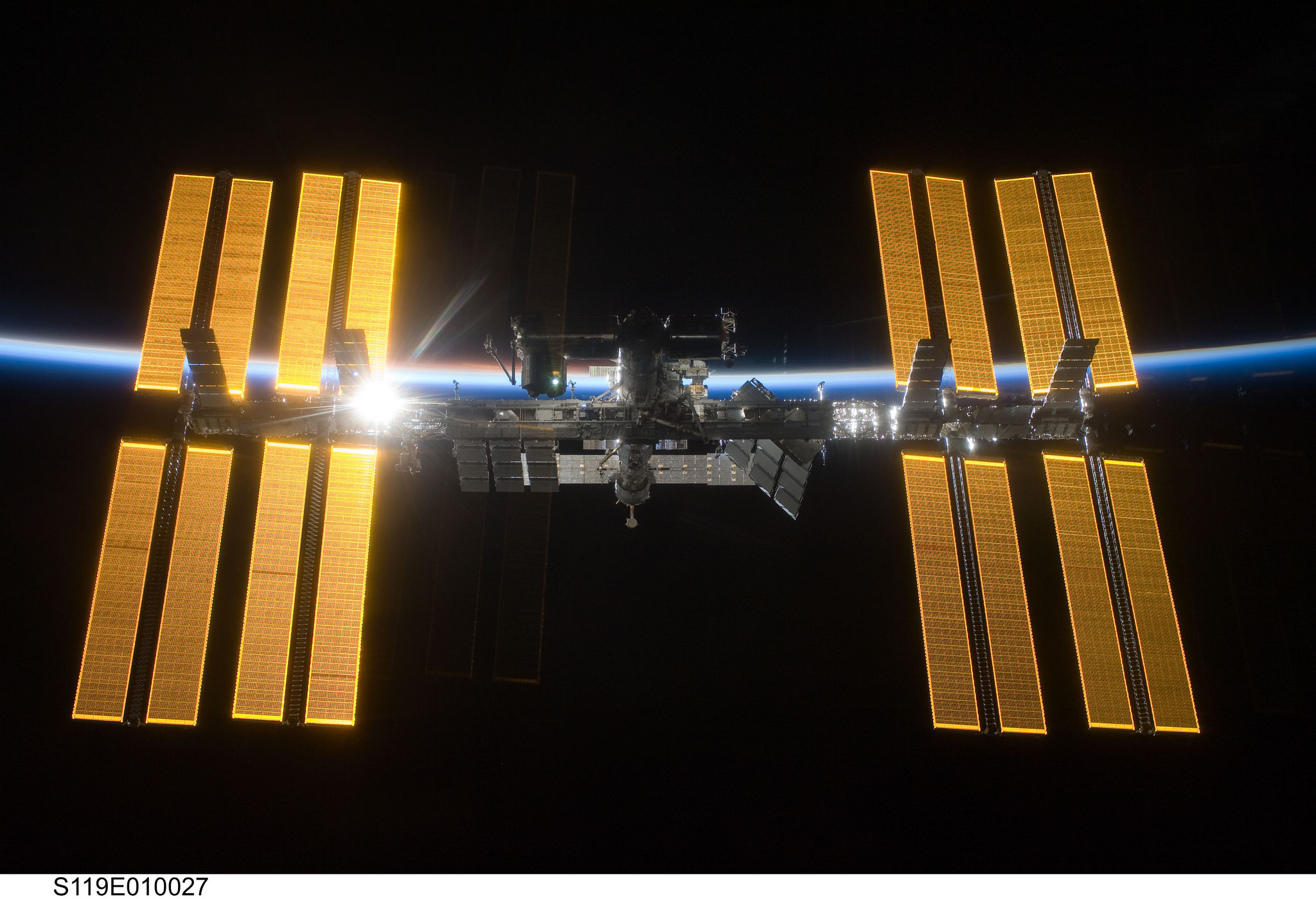

At 72.8 by 108.5 metres in size and orbiting the Earth once every 92 minutes at an average 400 kilometres in altitude, the ISS is the brightest object in low Earth orbit, and reaches magnitude -2 in brightness—not quite as bright as Venus at maximum brightness—on a good overhead pass. Depending on the approach angle, I can just make out a bit of detail when the ISS is near the zenith, looking like either a box, a close double star, or a tiny Star Wars TIE fighter through binoculars. Numerous apps and platforms exist to predict ISS passes based on location, though our favorite is still the venerable Heavens-Above. It’s strange to think, we were using Heavens-Above to chase Mir back in the late 1990s!

There’s another interesting challenge, which, to our knowledge, has never been captured as we near high beta angle season for the ISS: catching an ‘ISS wink out,’ or that brief sunset followed by sunrise a few minutes later on the same pass. It’s worth noting that the central United States may see just such an event during an early morning pass on June 4th… will you be the first to witness it?

Photographing the ISS is as easy as setting a DSLR on a tripod with a wide field of view lens, and doing a simple time exposure as it drifts by. Be sure to manually set the focus before the pass… Venus is currently well placed as a ‘mock ISS’ to get a fix on beforehand.

And amateur observers can even capture detail on the ISS, though this requires a camera running video coupled to a telescope. High precession tracking is desirable, though not mandatory: we’ve actually got descent results manually aiming a scope at the ISS with video running. The ISS appears in post production, occasionally skipping through the field of view.

PhD student Bob Lansdorp has made some great videos of the ISS with a similar rig.

Another unique method is to know when the ISS will transit the Sun, Moon or near a bright planet or star, aim your rig at the right spot, and let the station come to you. A good site to tailor alerts for such occurrences is CALSky.

After high beta angle season, missions to and from the ISS will resume. This includes the return of ISS crewmembers Shkaplerov, Christoforetti and Virts on June 7th, followed by a Soyuz launch with Kononeko, Yui, and Lindgren on July 24th. Also on tap is SpaceX’s Dragon capsule on CRS-7 launching on June 26th, the return to flight for Progress on July 3rd, and a HTV-5 launch for JAXA on August 17th. These can also provide interesting views for ground observers as well, as these spacecraft follow the ISS in its orbit on approach like tiny fainter ‘stars.’

A busy season indeed. Don’t miss a chance to see the ISS coming to a sky near you, and watch as humans work together aboard this orbiting science platform in space.