[/caption]

There’s a defunct 6.5-ton satellite heading our way. Trouble is, NASA’s not sure exactly where and when it might come down. And they’re not sure how much of it might survive its fiery fall through Earth’s atmosphere, either.

“Numerically, it comes out to a chance of 1-in-3,200 that one person anywhere in the world might be struck by a piece of debris,” said Nick Johnson, chief scientist with NASA’s Orbital Debris Program, during a media teleconference on Friday. “Those are obviously very, very low odds that anybody’s going to be impacted by this debris.”

Johnson reminded everyone that “throughout the entire 54 years of the space age, there have been no reports of anybody in the world being injured or severely impacted by any re-entering debris.”

How do you like your odds?

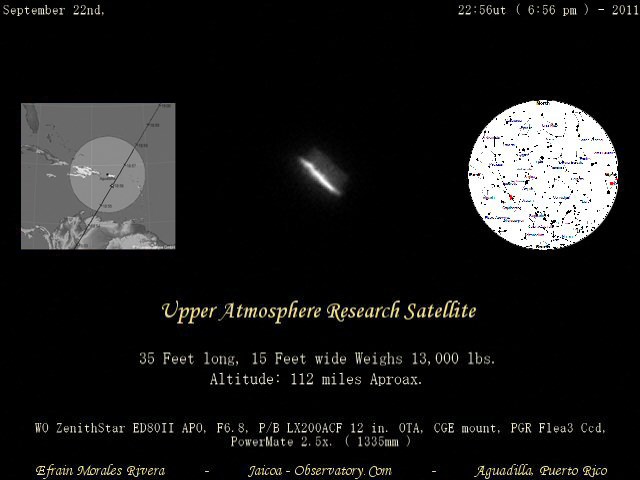

The huge 10-meter (35-ft) -long Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) is in an orbit that crosses over six continents and three oceans. Johnson said it is expected to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere in an uncontrolled fall in late September or early October. While much of the spacecraft is expected to burn up during re-entry, it’s likely some pieces will make it to the ground. Current projections on where debris field might be is a 800-km- (500-mile) wide swath from Northern Canada to Southern South America.

Yikes.

Or it might fall in the ocean.

“We do know with 99.9 percent accuracy that it will re-enter the atmosphere somewhere between 57 degrees north and 57 degrees south, which means it will be anywhere from northern Canada to southern South America,” said Major Michael Duncan, deputy chief of space situational awareness with the Air Force’s U.S. Strategic Command. “That is truly the best estimation we can give you at this point in time.”

There are about 26 components that are big enough to survive and make it down to Earth, the largest weighing more than 150 kg (330 pounds.)

But hey, this happens all the time.

“Satellites re-entering is actually very commonplace,” Johnson said. “Last year, for example, we averaged over one object per day falling back uncontrolled into the atmosphere,” and for those coming back in an uncontrolled fashion – meaning it is a crapshoot when and where they fall — there were 75 metric tons of spacecraft and rocket bodies falling back to Earth.

“In perspective, UARS is less than six metric tons,” Johnson added. “So it’s a very small percentage of the annual re-entry of satellites.”

The majority of these satellites, though, were a lot smaller than UARS and they burn up completely in the atmosphere.

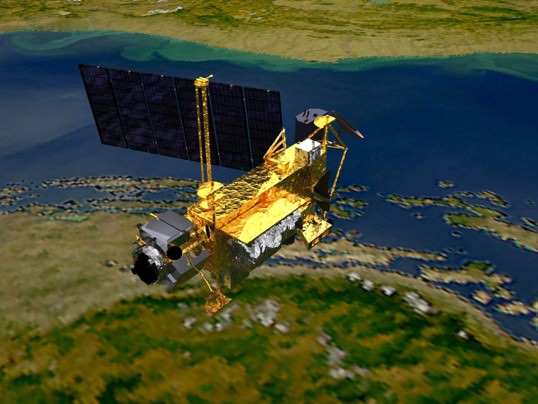

The UARS satellite launched from Space Shuttle Discovery in 1991. To give you an idea of how big the satellite is, it filled the shuttle’s payload bay completely. It had ten science instruments to examine the chemistry of the upper atmosphere and measure water vapor and other elements. It monitored the health of the ozone hole, looking at the amounts of aerosols in the atmosphere. In 2005 NASA determined that UARS was to be decommissioned.

It was never designed to be returned on the Space Shuttle, said Paul Hertz, chief scientist, NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

Hertz said NASA is trying to keep the public informed about the the possibilities of debris failing and want to be up front about it. They will post all current information on www.nasa.gov/uars.

And Space Command will be tracking the satellite and providing updates as to where and when UARS will come down, and provide impact predictions if it looks like it will be coming down over land.

Although there are no hazardous materials on board – unlike the hydrazine on a National Reconnaissance Office spy satellite that was shot down in 2008 to avoid contaminating Earth – it was stressed that if anyone finds a piece of the satellite, they should not pick it up, but notify the local authorities.

But anyone along the final trajectory should get “a nice show,” Johnson said.

“It is a relatively large vehicle,” he said. “It would be visible in daylight. Odds are, though, it’s going to happen over an ocean, unlikely to be seen unless it’s by an airliner. We’ve had reports like that before. Since we don’t know where it’s going to come in, we can’t raise people’s expectations and tell them to go out and look in their backyard. So it’ll be a serendipitous kind of event.”