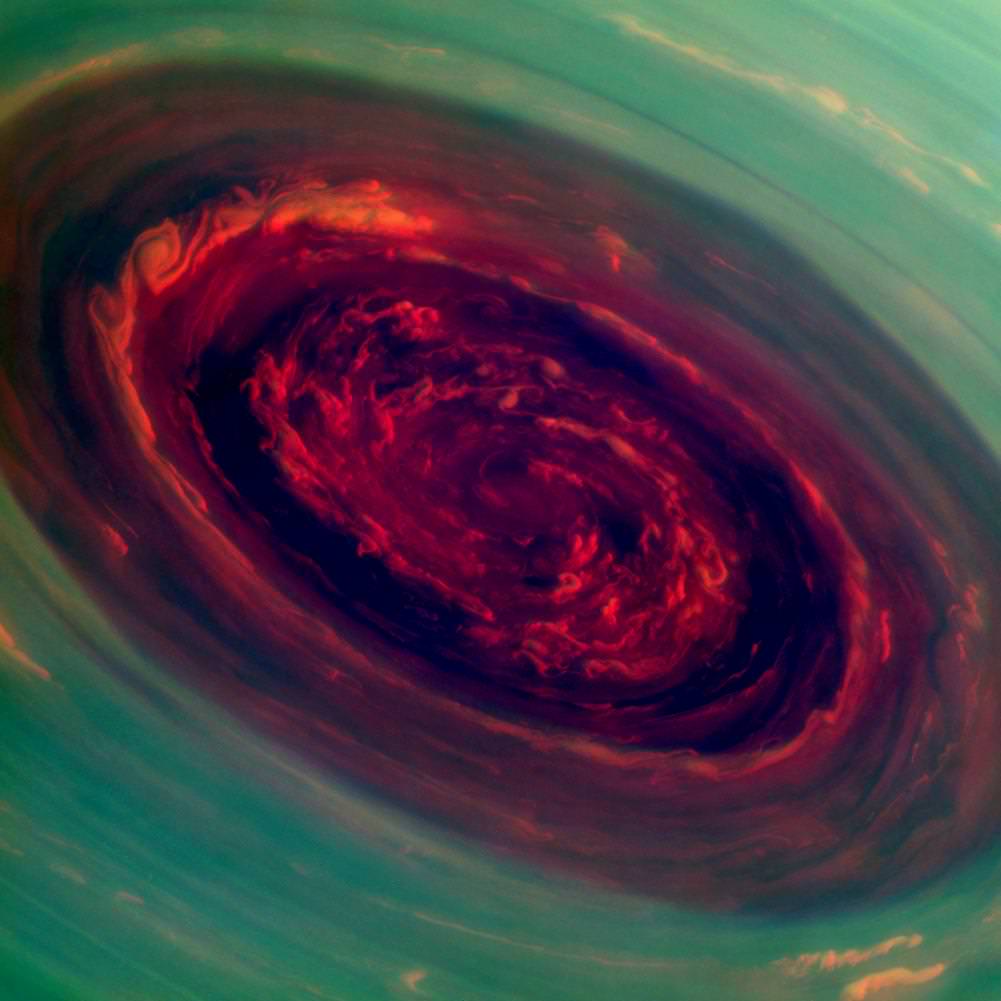

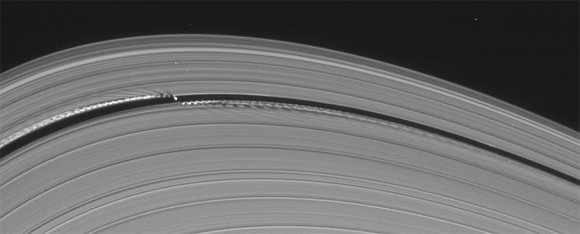

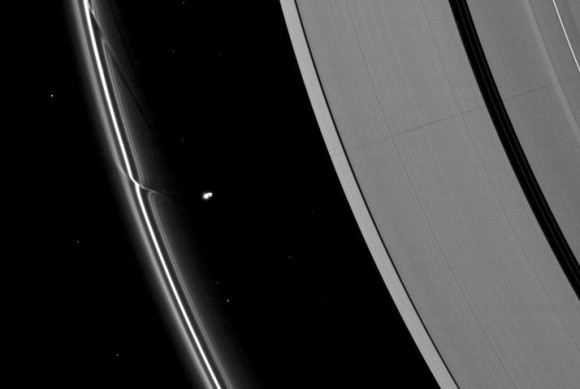

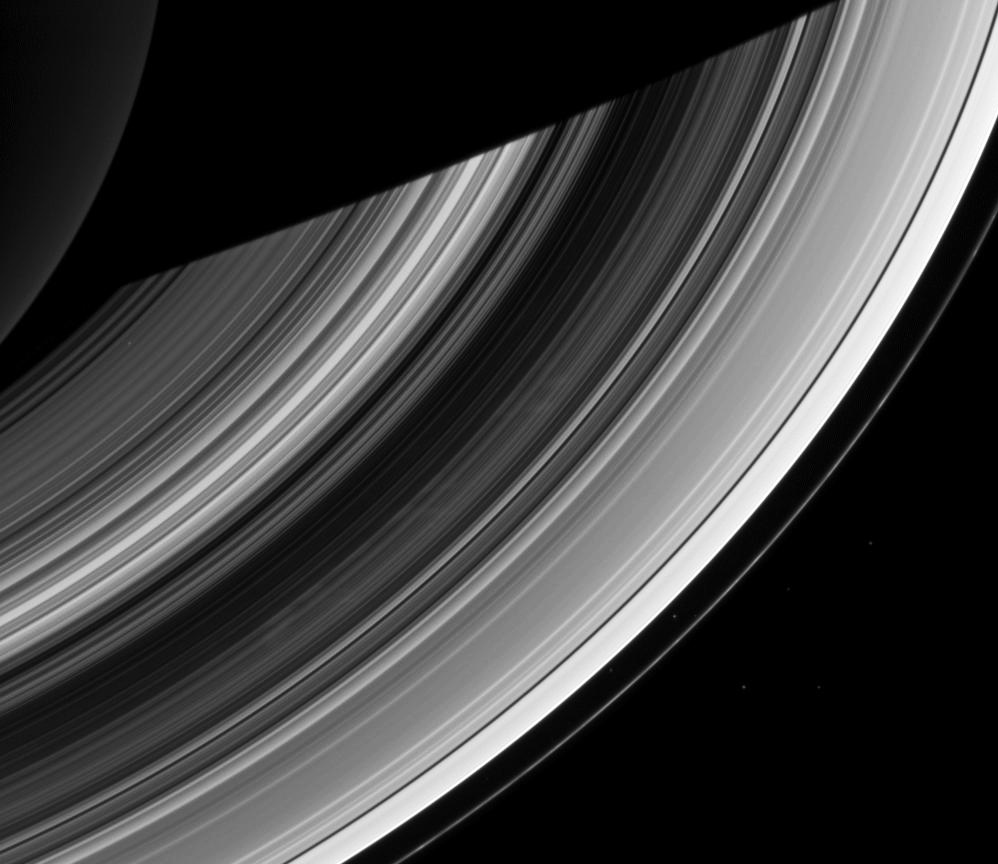

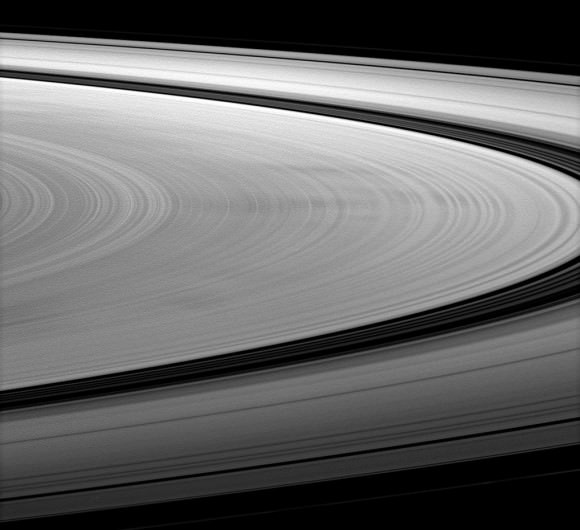

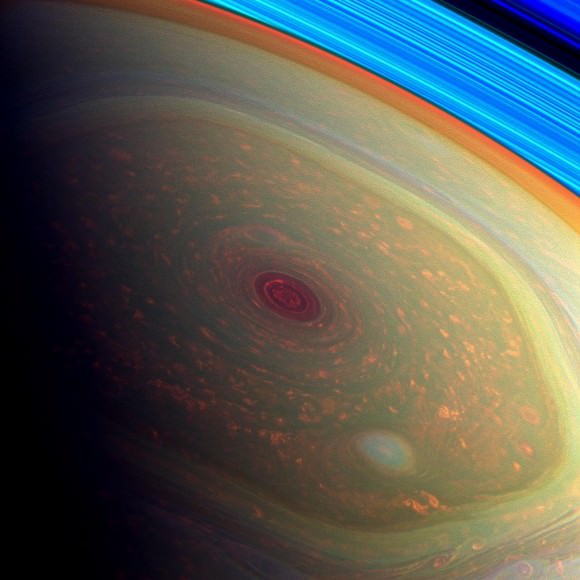

Checking out the above pictures of a Saturn hurricane, one can’t help but wonder: how close was the Cassini spacecraft to spiralling down into gassy nothingness?

These dizzying images of a hurricane on Saturn, of course, came as the spacecraft zoomed overhead at a safe distance. NASA’s goal in examining this huge hurricane is to figure out its mechanisms and to compare it to what happens on our home planet.

Hurricanes on Earth munch on water vapor to keep spinning. On Saturn, there’s no vast pool of water to draw from, but there’s still enough water vapor in the clouds to help scientists understand more about how hurricanes on Earth begin, and continue.

“We did a double take when we saw this vortex because it looks so much like a hurricane on Earth,” stated Andrew Ingersoll, a Cassini imaging team member at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “But there it is at Saturn, on a much larger scale, and it is somehow getting by on the small amounts of water vapor in Saturn’s hydrogen atmosphere.”

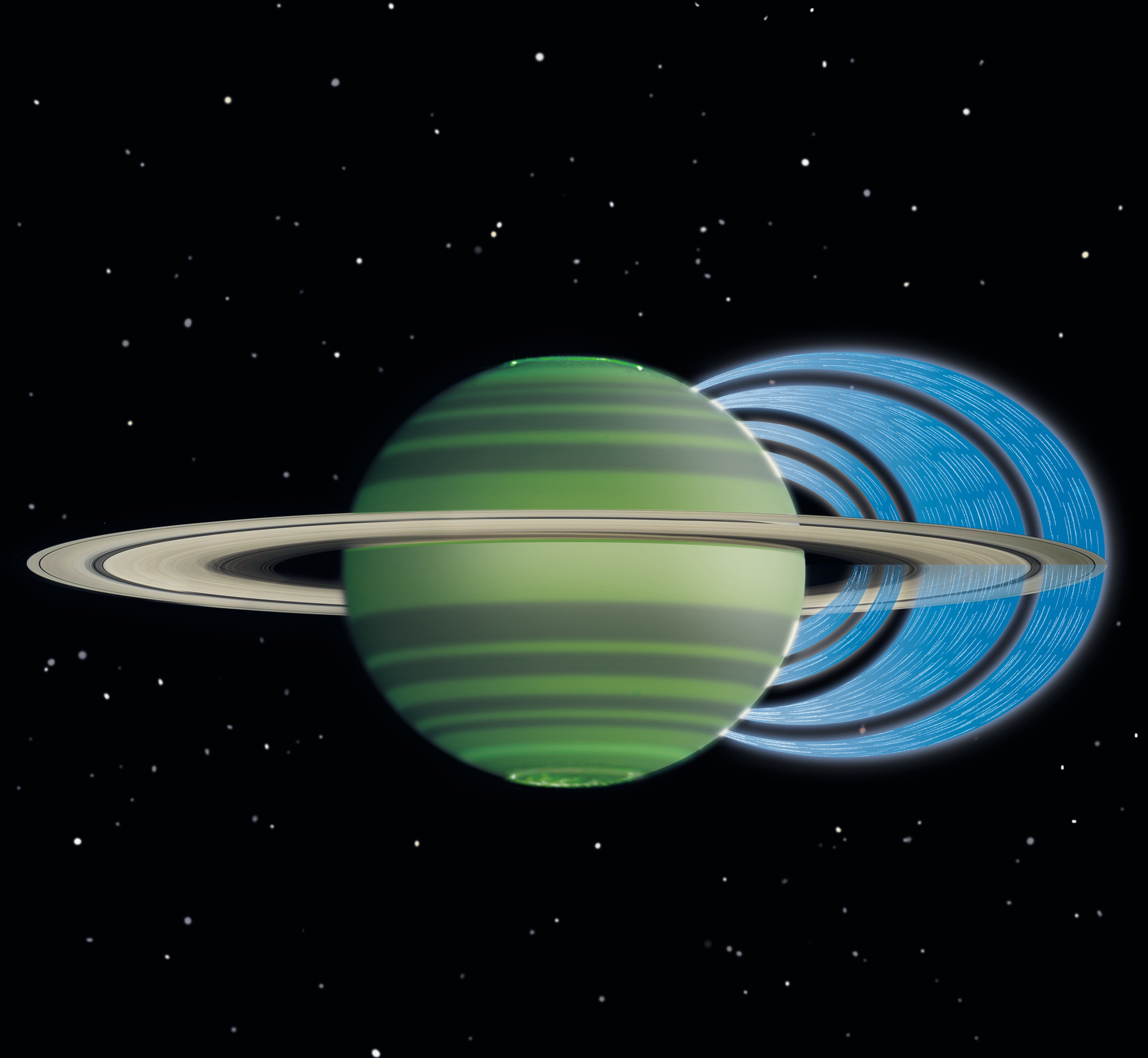

There’s one big change in hurricane activity you’d observe if suddenly shifted from Earth to Saturn: this behemoth — 1,250 miles (2,000 kilometers) wide, about 20 times its Earthly counterparts — spins a heckuva lot faster.

In the eye, winds in the wall speed more than four times faster than what you’d find on Earth. The hurricane also sticks around at the north pole. On Earth, hurricanes head north (and eventually dissipate) due to wind forces generated by the planet’s rotation.

“The polar hurricane has nowhere else to go, and that’s likely why it’s stuck at the pole,” stated Kunio Sayanagi, a Cassini imaging team associate at Hampton University in Hampton, Va.

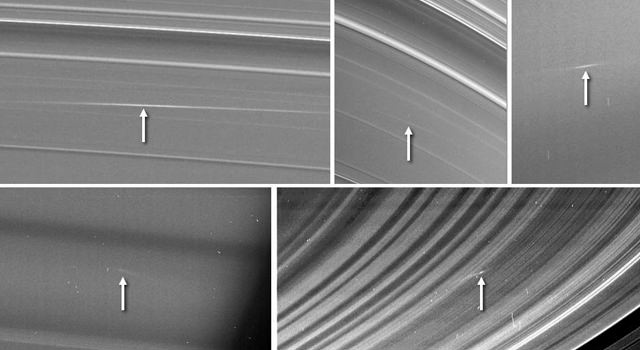

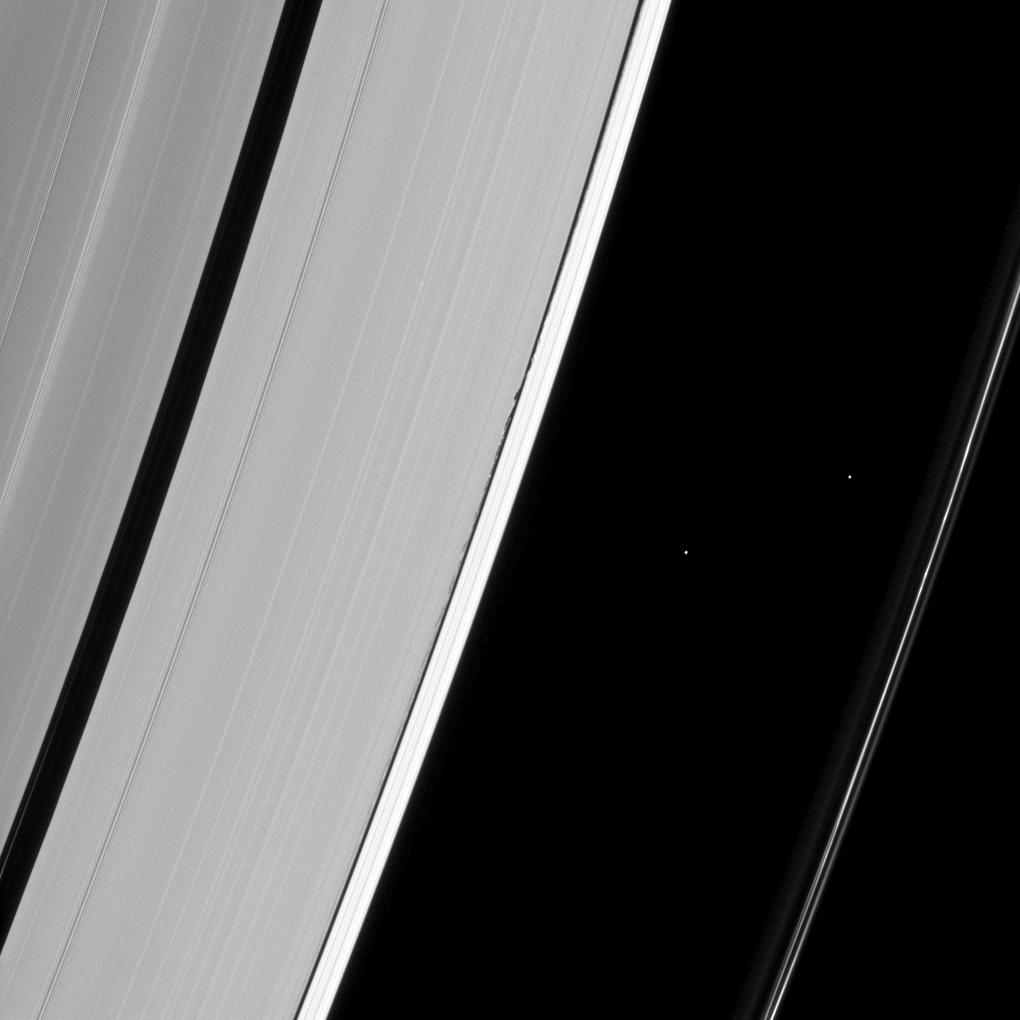

Cassini initially spotted the storm in 2004 through its heat-seeking infrared camera, when the north pole was shrouded in darkness during winter.

The spacecraft first caught the storm in visible light in 2009, when NASA controllers altered Cassini’s orbit so that it could view the poles.

Saturn, of course, is not the only gas giant in the solar system with massive hurricanes. Jupiter’s Great Red Spot has been raging since before humans first spotted it in the 1600s. It appears to be shrinking, and could become circular by 2040.

Neptune also has hurricanes that can reach speeds of 1,300 miles (2,100 kilometers) an hour despite its cold nature; it even had a Great Dark Spot spotted during Voyager’s flypast in 1989 that later faded from view. Uranus, which scientists previously believed was quiet, is a pretty stormy place as well.

Check out this YouTube video for more details on how Saturn’s storm works.

Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory