Chances are, at one time or another, we’ve all used Google Maps to find the shortest route from point A to point B. But if you are like some people, you’ve used this mapping tool to have a look at geographical features or places you hope to visit someday. In an age where digital technology is allowing for telecommuting and even telepresence, it’s nice to take virtual tours of the places we may never get to see in person.

But now, Google Maps is using its technology to enable the virtual exploration of something far grander: the Solar System! Thanks to images provided by the Cassini orbiter of the planets and moons it studied during its 20 year mission, Google is now allowing users to explore places like Venus, Mercury, Mars, Europa, Ganymede, Titan, and other far-off destinations that are impossible for us to visit right now.

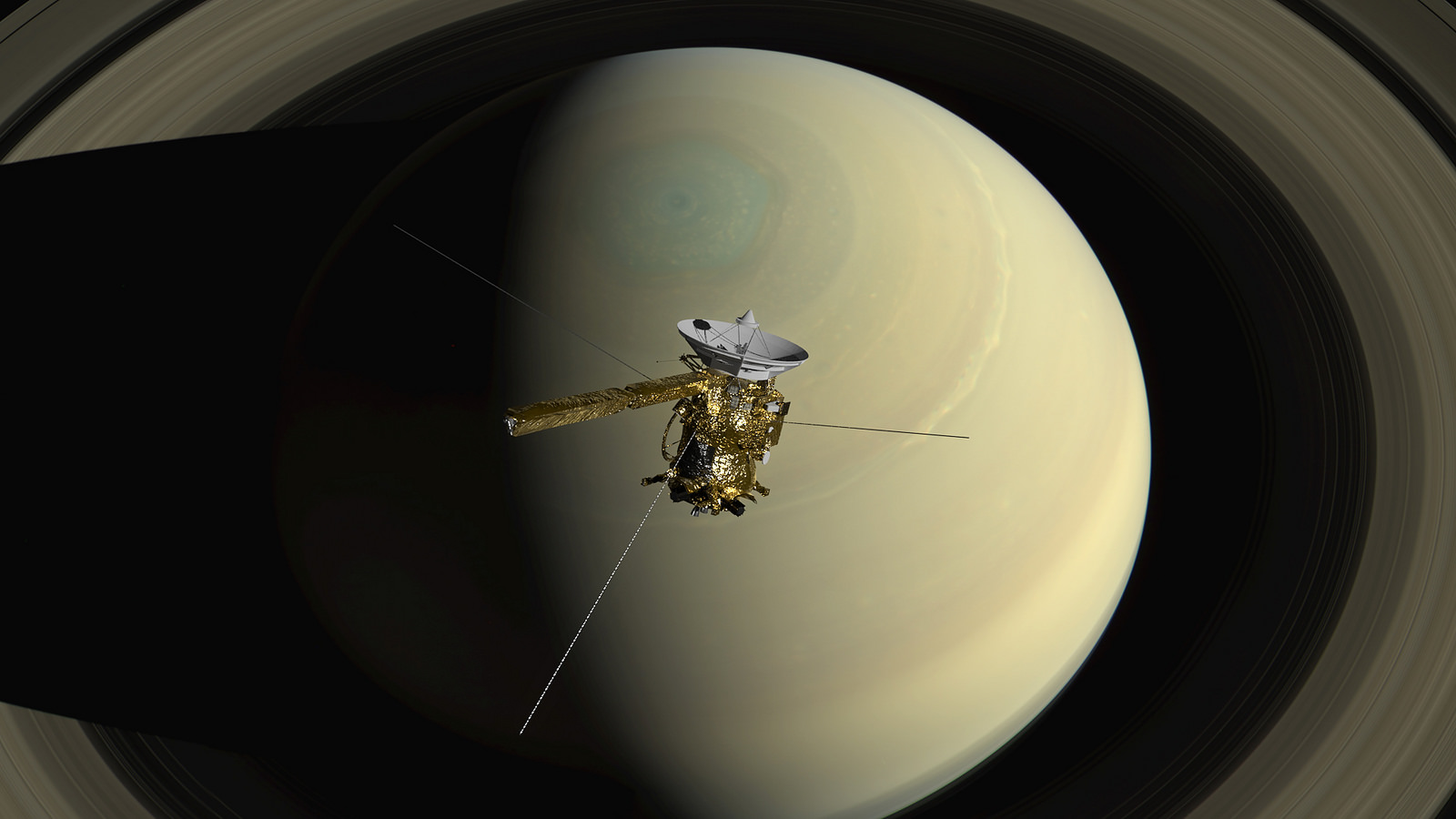

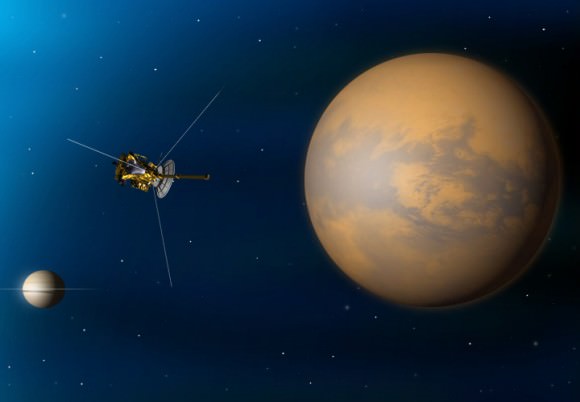

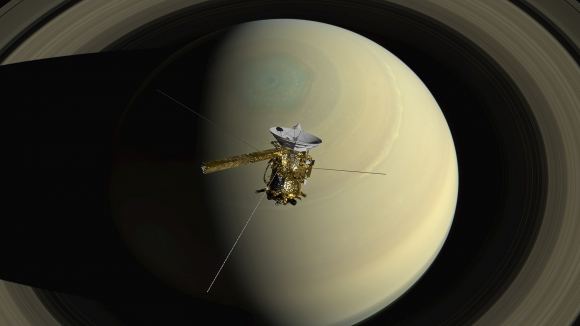

Similar to how Google Earth uses satellite imagery to create 3D representations of our planet, this new Google Maps tool relies on the more than 500,000 images taken by Cassini as it made its way across the Solar System. This probe recently concluded its 20 year mission, 13 of which were spent orbiting Saturn and studying its system of moons, by crashing into the atmosphere of Saturn.

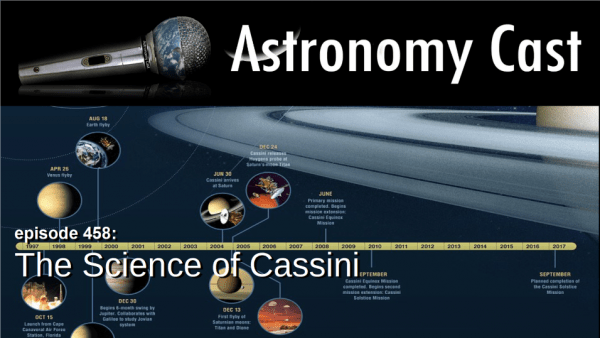

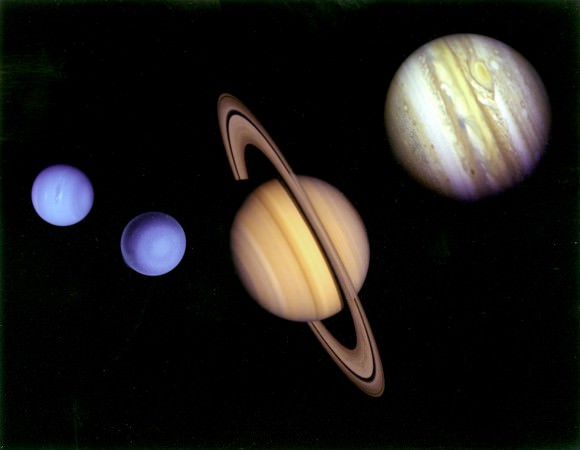

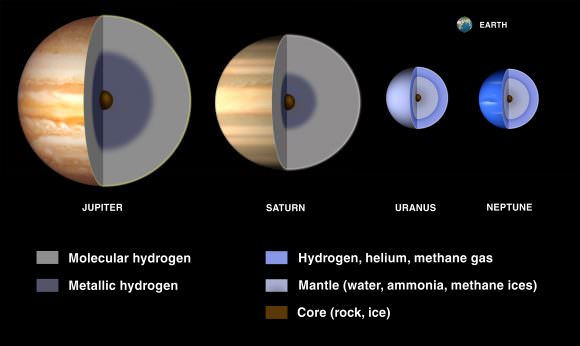

After launching from Earth on October 15th, 1997, Cassini conducted a flyby of Venus in order to pick up a gravity-assist. It then flew by Earth, obtaining a second gravity-assist, while making its way towards the Asteroid Belt. Before reaching the Saturn System, where it would begin studying the gas giant and its moons, Cassini also conducted a flyby of Jupiter – snapping pictures of its moons, rings, and Great Red Spot.

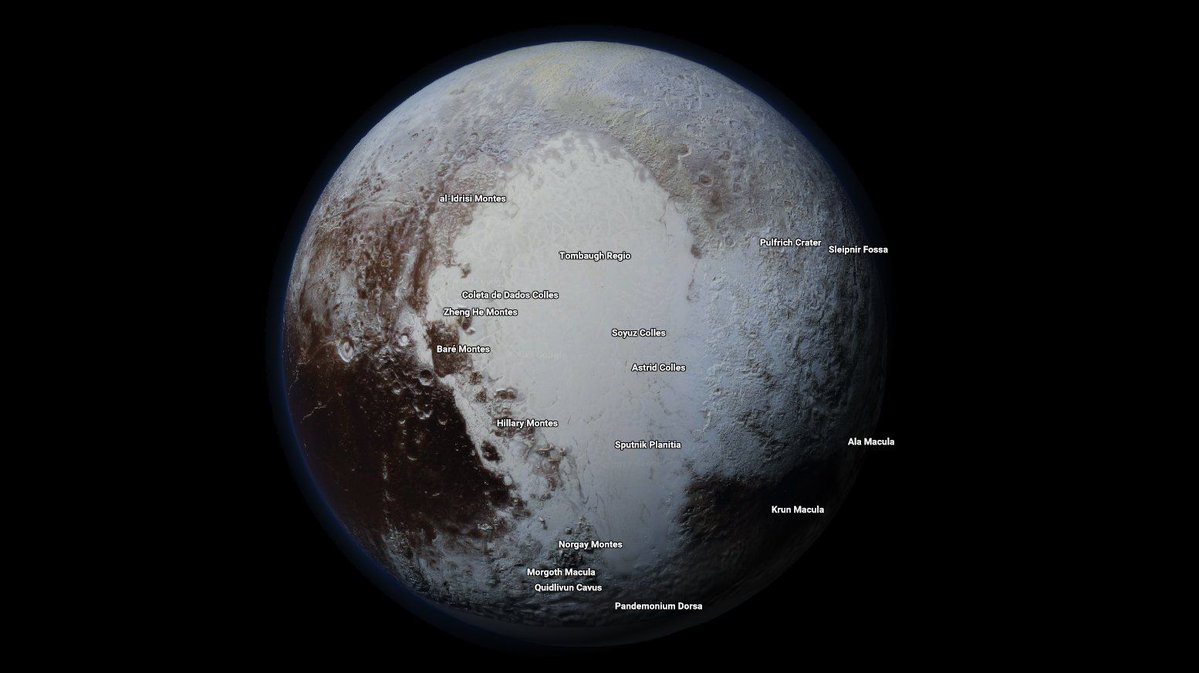

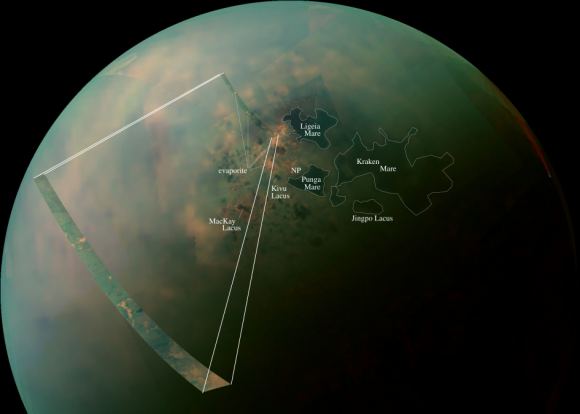

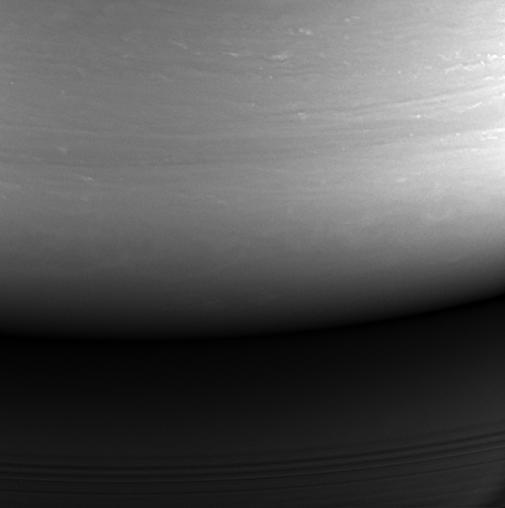

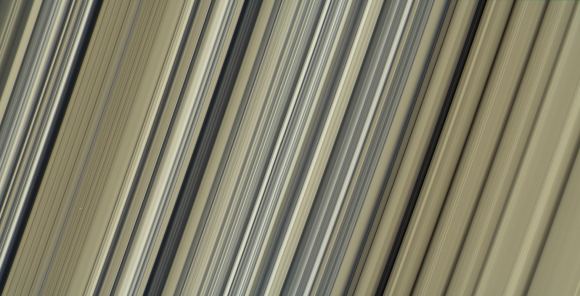

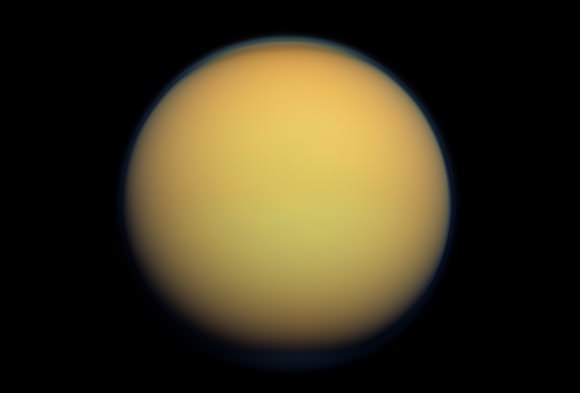

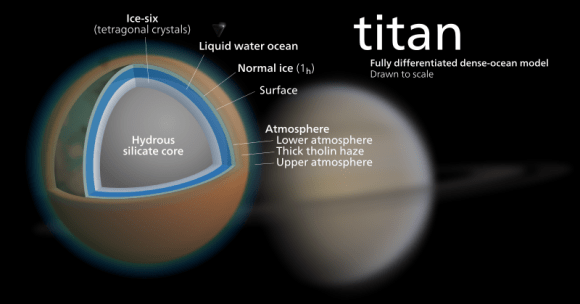

When it reached Saturn in July of 2004, Cassini went to work studying the planet and its larger moons – particularly Titan and Enceladus. During the next 13 years and 76 days, the probe would provide breathtaking images and sensor data on Saturn’s rings, atmosphere and polar storms and reveal things about Titan’s surface that were never before seen (such as its methane lakes, hydrological cycle, and surface features).

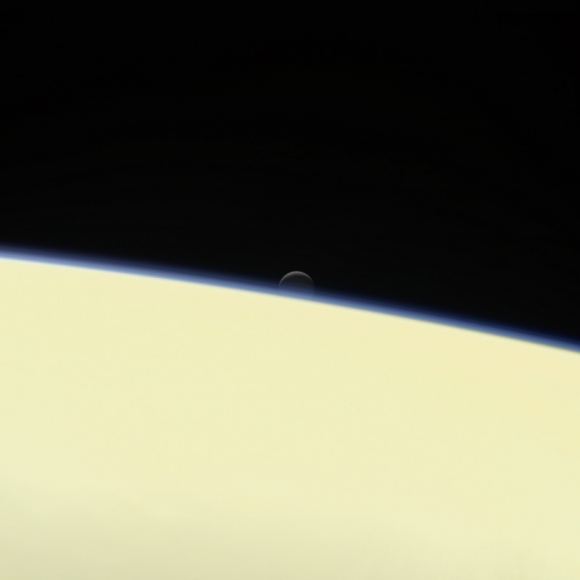

It’s flybys of Enceladus also revealed some startling things about this icy moon. Aside from detecting a tenuous atmosphere of ionized water vapor and Enceladus’ mysterious “Tiger Stripes“, the probe also detected jets of water and organic molecules erupting from the moon’s southern polar region. These jets, it was later determined, were indicative of a warm water ocean deep in the moon’s interior, and possibly even life!

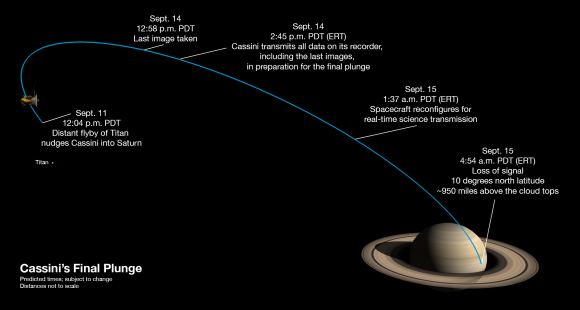

Interestingly enough, the original Cassini mission was only planned to last for four years once it reached Saturn – from June 2004 to May 2008. But by the end of this run, the mission was extended with the Cassini Equinox Mission, which was intended to run until September of 2010. It was extended a second time with the Cassini Solstice Mission, which lasted until September 15th, 2017, when the probe was crashed into Saturn’s atmosphere.

Thanks to all the images taken by this long-lived mission, Google Maps is now able to offer exploratory tours of 16 celestial bodies in the Solar System – 12 of which are new to the site. These include Earth, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Pluto, Ceres, Io, Europa, Ganymede, Mimas, Enceladus, Dione, Rhea, Titan, Iapetus and (available as of July 2017) the International Space Station.

This latest development also builds on several extensions Google has released over the years. These include Google Moon, which was released on July 20th, 2005, to coincide with the 36th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon Landing. Then there was Google Sky (introduced in 2007), which used photographs taken by the Hubble Space Telescope to create a virtual map of the visible universe.

Then there was Google Mars, the result of a collaborative effort between Google and NASA scientists at the Mars Space Flight Facility released in 2011, one year before the Curiosity rover landed on the Red Planet. This tool relied on data collected by the Mars Global Surveyor and the Mars Odyssey missions to create high-resolution 3D terrain maps that included elevations.

In an age of high-speed internet and telecommunications, using the internet to virtually explore the many planets and bodies of the Solar System just makes sense. Especially when you consider that even the most ambitious plans to conduct tourism to Mars or the Moon (looking at you, Elon Musk and Richard Branson!) are not likely to bear fruit for many years, and cost an arm and a leg to boot!

In the future, similar technology could lead to all kinds of virtual exploration. This concept, which is often referred to as “telexploration”, would involve robotic missions traveling to other planets and even star systems. The information they gather would then be sent back to Earth to create virtual experiences, which would allow scientists and space-exploration enthusiasts to feel like they were seeing it firsthand.

In truth, this mapping tool is just the latest gift to be bestowed by the late Cassini mission. NASA scientists expect to be sifting through the volumes of data collected by the orbiter for years to come. Thanks to improvements made in software applications and the realms of virtual and augmented reality, this data (and that of present and future missions) is likely to be put to good use, enabling breathtaking and educational tours of our Universe!

Further Reading: Make Use Of