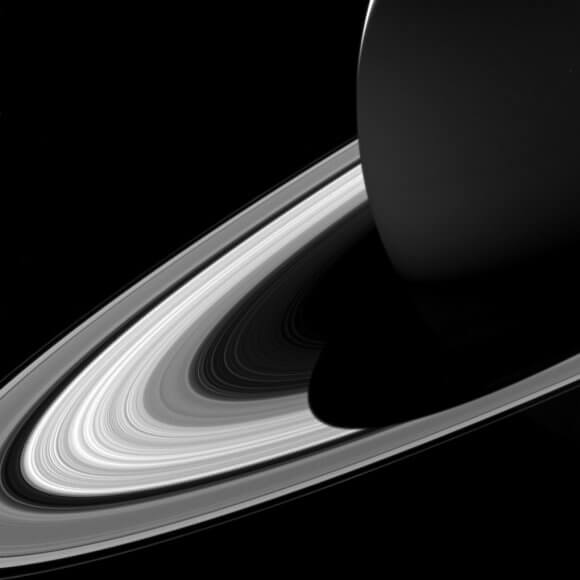

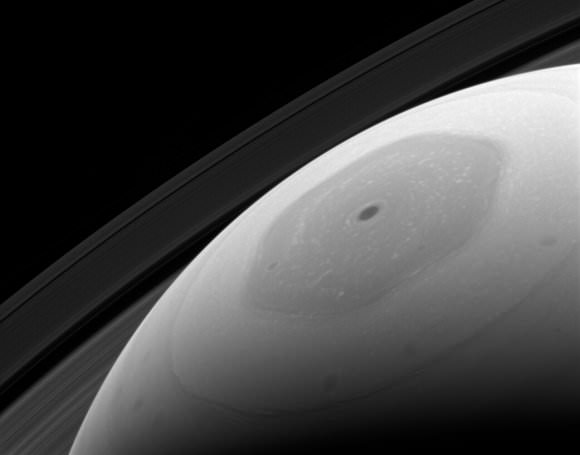

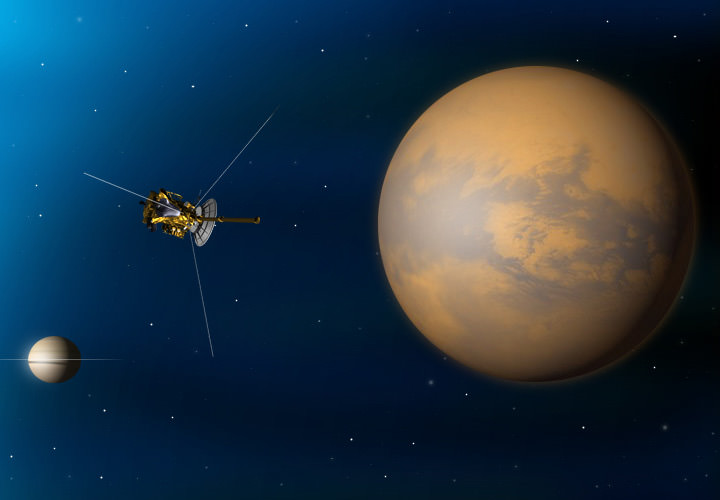

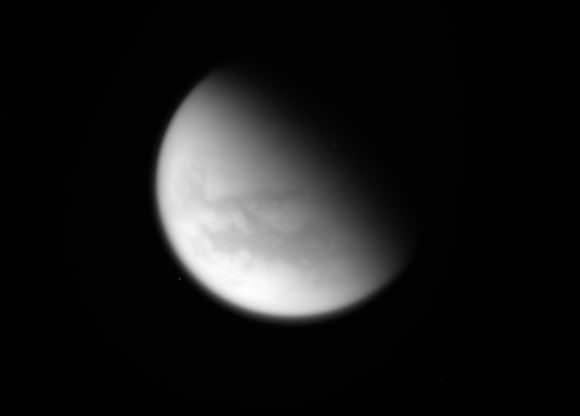

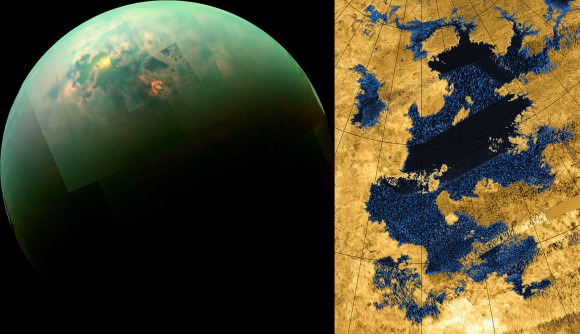

Ever since the Cassini orbiter and the Huygens lander provided us with the first detailed glimpse of Saturn’s moon Titan, scientists have been eager to mount new missions to this mysterious moon. Between its hydrocarbon lakes, its surface dunes, its incredibly dense atmosphere, and the possibility of it having an interior ocean, there is no shortage of things that are worthy of research.

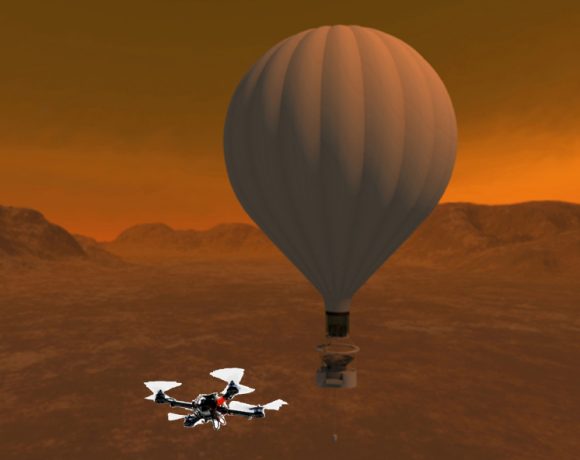

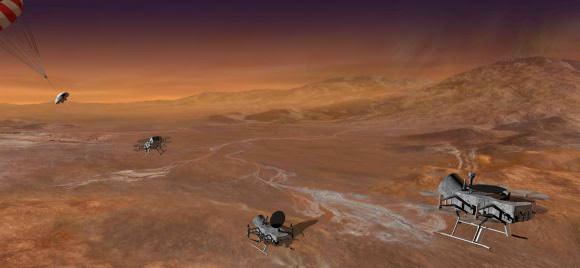

The only question is, what form would this mission take (i.e. aerial drone, submarine, balloon, lander) and where should it set down? According to a new study led by the University of Texas at Austin, Titan’s methane lakes are very calm and do not appear to experience high waves. As such, these seas may be the ideal place for future missions to set down on the moon.

Their study, which was titled “Surface Roughness of Titan’s Hydrocarbon Seas“, appeared in the June 29th issue of the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Led by Cyril Grima, a research associate at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), the team behind the study sought to determine just how active the lakes are in Titan’s northern polar region are.

As Grima explained in a University of Texas press release, this research also shed light on the meteorological activity on Titan:

“There’s a lot of interest in one day sending probes to the lakes, and when that’s done, you want to have a safe landing, and you don’t want a lot of wind. Our study shows that because the waves aren’t very high, the winds are likely low.”

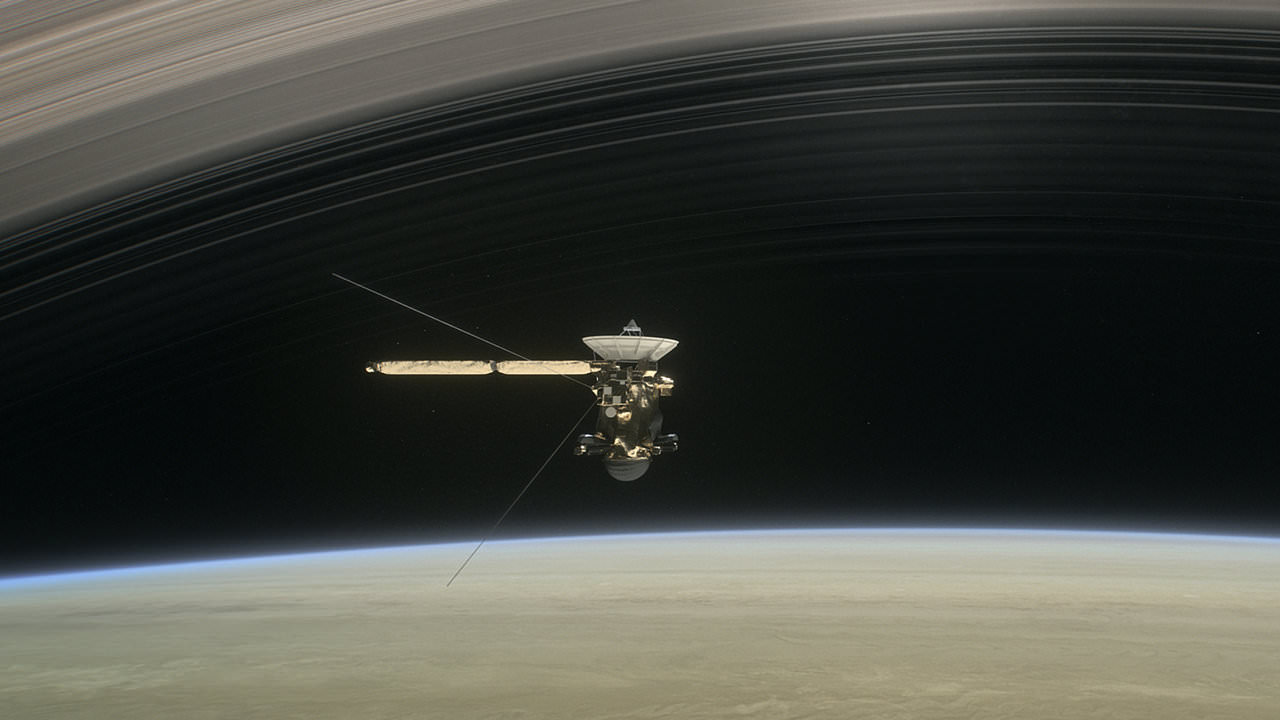

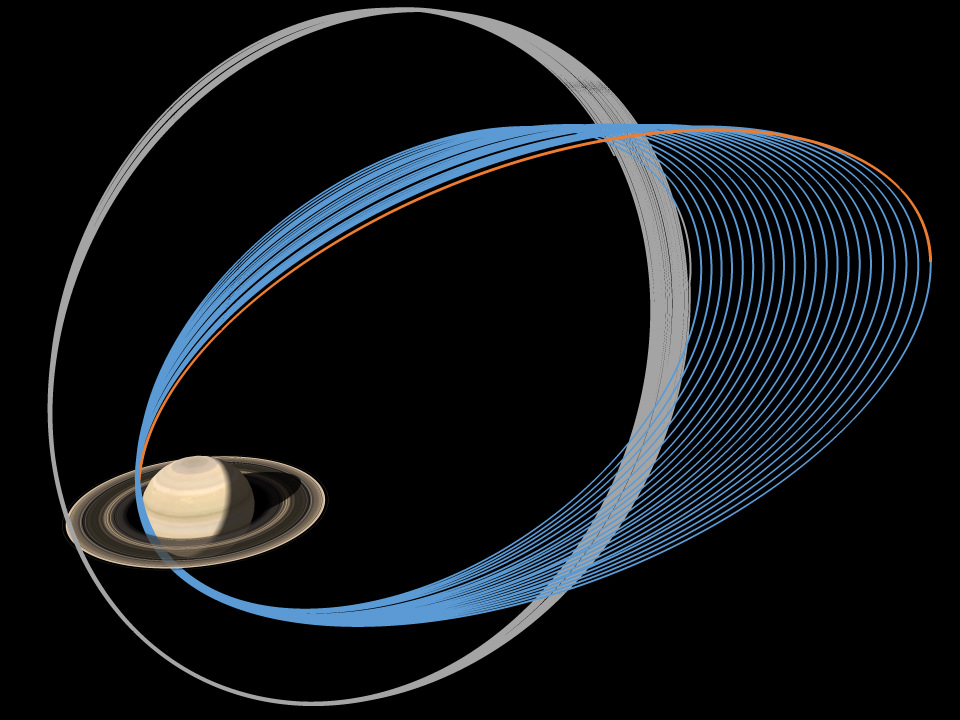

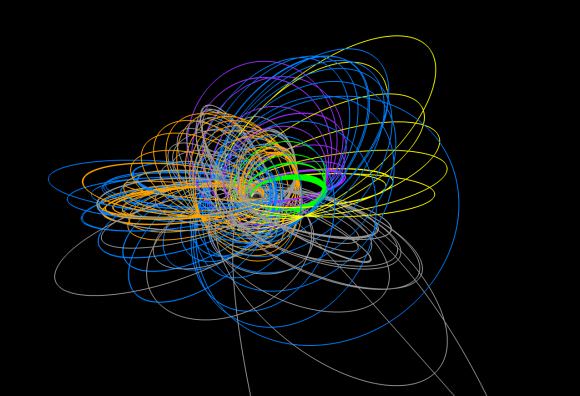

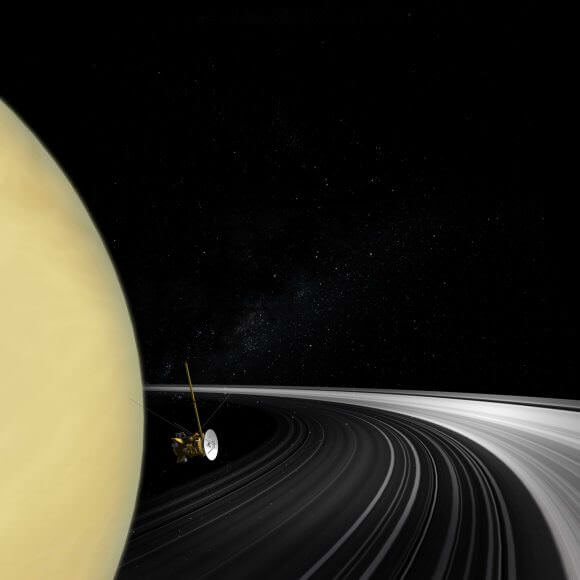

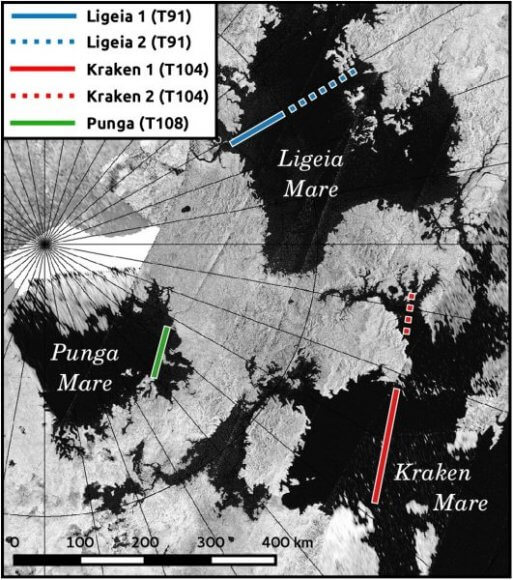

Towards this end, Grima and his colleagues examined radar data obtained by the Cassini mission during Titan’s early summer season. This consisted of measurements of Titan’s northern lakes, which included Ontario Lacus, Ligeia Mare, Punga Mare, and Kraken Mare. The largest of the three, Kraken Mars, is estimated to be larger than the Caspian Sea – i.e. 4,000,000 km² (1,544,409 mi²) vs 3,626,000 km2 (1,400,000 mi²).

With the help of the Cassini RADAR Team and researchers from Cornell University, the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and elsewhere, the team applied a technique known as radar statistical reconnaissance. Developed by Grima, this technique relies on radar data to measure the roughness of surfaces in minute detail.

This technique has also been used to measure snow density and the surface roughness of ice in Antarctica and the Arctic. Similarly, NASA has used the technique for the sake of selecting a landing site on Mars for their Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (Insight) lander, which is scheduled to launch next year.

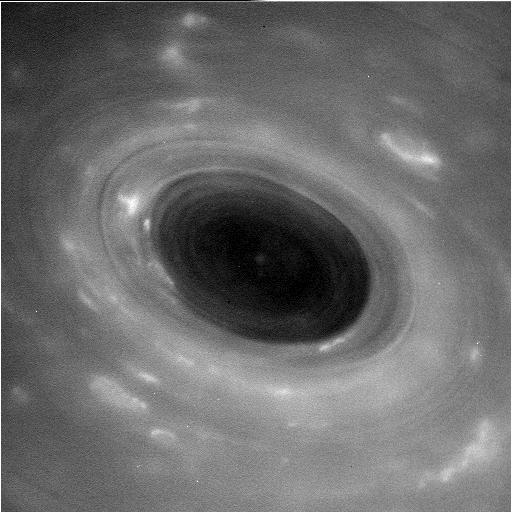

From this, Grima and his colleagues determined that waves on these lakes are quite small, reaching only 1 cm in height and 20 cm in length. These findings indicate that these lakes would be a serene enough environment that future probes could make soft landings on them and then begin the task of exploring the surface of the moon. As with all bodies, waves on Titan could be wind-driven, triggered by tidal flows, or the result of rain or debris.

As a result, these results are calling into question what scientists think about seasonal change on Titan. In the past, it was believed that summer on Titan was the beginning of moon’s windy season. But if this were the case, the results would have indicated higher waves (the result of higher winds). As Alex Hayes, an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University and a co-author on the study, explained:

“Cyril’s work is an independent measure of sea roughness and helps to constrain the size and nature of any wind waves. From the results, it looks like we are right near the threshold for wave generation, where patches of the sea are smooth and patches are rough.”

These results are also exciting for scientists who are hoping to plot future missions to Titan, especially by those who are hoping to see a robotic submarine sent to Titan’s to investigate its lakes for possible signs of life. Other mission concepts involve exploring Titan’s interior ocean, its surface, and its atmosphere for the sake of learning more about the moon’s environment, its organic-rich environment and probiotic chemistry.

And who knows? Maybe, just maybe, these missions will find that life in our Solar System is more exotic than we give it credit before, going beyond the carbon-based life that we are familiar with to include the methanogenic.

Further Reading: University of Texas JSG, Earth and Planetary Science Letters