Terraforming. Chances are you’ve heard that word uttered before, most likely in the context of some science fiction story. However, in recent years, thanks to renewed interest in space exploration, this word is being used in an increasingly serious manner. And rather than being talked about like a far-off prospect, the issue of terraforming other worlds is being addressed as a near-future possibility.

In recent years, we’ve heard luminaries like Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking claiming that humanity needs a “backup location” to ensure our survival, private ventures like Mars One enlisting thousands of volunteers to colonize the Red Planet, and space agencies like NASA, the ESA, and China discussing the prospect of long-term habitability on Mars or the Moon. From all indications, it looks like terraforming is yet another science-fiction concept that is migrating into the realm of science fact.

But just what does terraforming entail? Where exactly could we go about using this process? What kind of technology would we need? Does such technology already exist, or do we have to wait? How much in the way of resources would it take? And above all, what are the odds of it succeeding? Answering any or all of these questions requires a bit of digging. Not only is terraforming a time-honored concept, but as it turns out, humanity already has quite a bit of experience in this area!

Origin Of The Term:

To break it down, terraforming is the process whereby a hostile environment (i.e., a planet that is too cold, too hot, and/or has an unbreathable atmosphere) is altered to make it suitable for human life. This could involve modifying the temperature, atmosphere, surface topography, ecology, or all of the above to make a planet or moon more “Earth-like.”

The term was coined by Jack Williamson, an American science fiction writer who has also been called “the Dean of science fiction” (after the death of Robert Heinlein in 1988). The term appeared as part of a science-fiction story, titled “Collision Orbit,” published in the 1942 edition of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction. This is the first known mention of the concept, though there are examples of it appearing in fiction beforehand.

Terraforming in Fiction:

Science fiction is filled with examples of altering planetary environments to be more suitable to human life, many of which predate scientific studies by many decades. For example, in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, he mentions at one point how the Martian invaders begin transforming Earth’s ecology for the sake of long-term habitation.

In Olaf Stapleton’s Last And First Men (1930), two chapters are dedicated to describing how humanity’s descendants terraform Venus after Earth becomes uninhabitable. In the process, they commit genocide against the native aquatic life. By the 1950s and 60s, due to the beginning of the Space Age, terraforming appeared in works of science fiction with increasing frequency.

One such example is Farmer in the Sky (1950) by Robert A. Heinlein. In this novel, Heinlein offers a vision of Jupiter’s moon Ganymede that is being transformed into an agricultural settlement. This was a very significant work, in that it was the first where the concept of terraforming is presented as a serious and scientific matter, rather than the subject of mere fantasy.

In 1951, Arthur C. Clarke wrote the first novel in which the terraforming of Mars was presented in fiction. Titled The Sands of Mars, the story involves Martian settlers heating up the planet by converting Mars’ moon Phobos into a second sun and growing plants that break down the Martian sands in order to release oxygen. In his seminal book 2001: A Space Odyssey – and its sequel, 2010: Odyssey Two – Clarke presents a race of ancient beings (“Firstborn”) turning Jupiter into a second sun so that Europa will become a life-bearing planet.

Poul Anderson also wrote extensively about terraforming in the 1950s. In his 1954 novel, The Big Rain, Venus is altered through planetary engineering techniques over a very long period of time. The book was so influential that the term term “Big Rain” has since come to be synonymous with the terraforming of Venus. This was followed in 1958 by the Snows of Ganymede, where the Jovian moon’s ecology is made habitable through a similar process.

In Issac Asimov’s Robot series, colonization and terraforming are performed by a powerful race of humans known as “Spacers,” who conduct this process on fifty planets in the known universe. In his Foundation series, humanity has effectively colonized every habitable planet in the galaxy and terraformed them to become part of the Galactic Empire.

In 1984, James Lovelock and Michael Allaby wrote what is considered by many to be one of the most influential books on terraforming. Titled The Greening of Mars, the novel explores the formation and evolution of planets, the origin of life, and Earth’s biosphere. The terraforming models presented in the book actually foreshadowed future debates regarding the goals of terraforming.

In the 1990s, Kim Stanley Robinson released his famous trilogy that deals with the terraforming of Mars. Known as the Mars Trilogy – Red Mars, Green Mars, Blue Mars – this series centers on the transformation of Mars over the course of many generations into a thriving human civilization. This was followed up in 2012 with the release of 2312, which deals with the colonization of the Solar System – including the terraforming of Venus and other planets.

Countless other examples can be found in popular culture, ranging from television and print to films and video games.

Study of Terraforming:

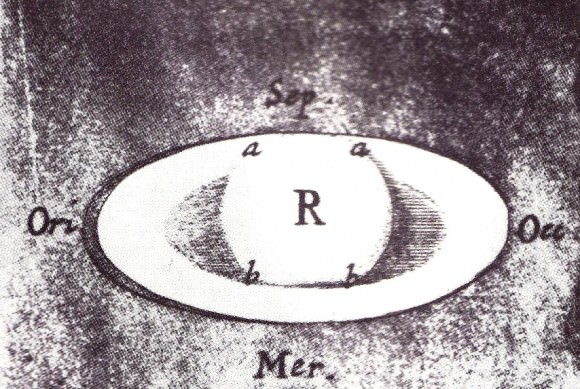

In an article published by the journal Science in 1961, famed astronomer Carl Sagan proposed using planetary engineering techniques to transform Venus. This involved seeding the atmosphere of Venus with algae, which would convert the atmosphere’s ample supplies of water, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide into organic compounds and reduce Venus’ runaway greenhouse effect.

In 1973, he published an article in the journal Icarus titled “Planetary Engineering on Mars,” where he proposed two scenarios for transforming Mars. These included transporting low albedo material and/or planting dark plants on the polar ice caps to ensure it absorbed more heat, melted, and converted the planet to more “Earth-like conditions.”

In 1976, NASA addressed the issue of planetary engineering officially in a study titled “On the Habitability of Mars: An Approach to Planetary Ecosynthesis.” The study concluded that photosynthetic organisms, the melting of the polar ice caps, and the introduction of greenhouse gases could all be used to create a warmer, oxygen, and ozone-rich atmosphere. The first conference session on terraforming – referred to as “Planetary Modeling” at the time- was organized that same year.

And then in March of 1979, NASA engineer and author James Oberg organized the First Terraforming Colloquium – a special session at the Tenth Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, which is held annually in Houston, Texas. In 1981, Oberg popularized the concepts that were discussed at the colloquium in his book New Earths: Restructuring Earth and Other Planets.

In 1982, Planetologist Christopher McKay wrote “Terraforming Mars”, a paper for the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. In it, McKay discussed the prospects of a self-regulating Martian biosphere, which included both the required methods for doing so and the ethics of it. This was the first time that the word terraforming was used in the title of a published article, and would henceforth become the preferred term.

This was followed by James Lovelock and Michael Allaby’s The Greening of Mars in 1984. This book was one of the first to describe a novel method of warming Mars, where chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are added to the atmosphere in order to trigger global warming. This book motivated biophysicist Robert Haynes to begin promoting terraforming as part of a larger concept known as Ecopoiesis.

Derived from the Greek words oikos (“house”) and poiesis (“production”), this word refers to the origin of an ecosystem. In the context of space exploration, it involves a form of planetary engineering where a sustainable ecosystem is fabricated from an otherwise sterile planet. As described by Haynes, this begins with the seeding of a planet with microbial life, which leads to conditions approaching that of a primordial Earth. This is then followed by the importation of plant life, which accelerates the production of oxygen, and culminates in the introduction of animal life.

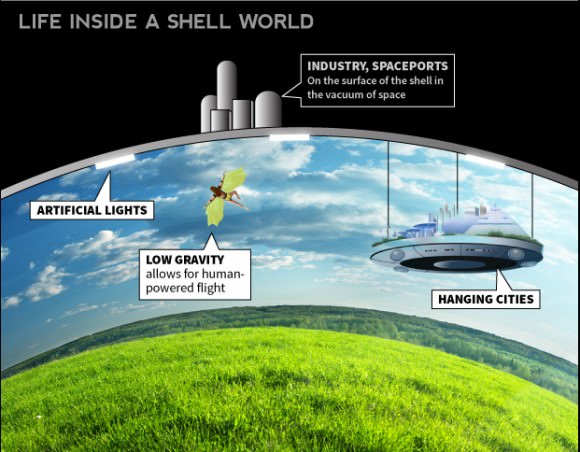

In 2009, Kenneth Roy – an engineer with the US Department of Energy – presented his concept for a “Shell World” in a paper published with the Journal of British Interplanetary Sciences. Titled “Shell Worlds – An Approach To Terraforming Moons, Small Planets and Plutoids“, his paper explored the possibility of using a large “shell” to encase an alien world, keeping its atmosphere contained long enough for long-term changes to take root.

There is also the concept where a usable part of a planet is enclosed in a dome in order to transform its environment, which is known as “paraterraforming”. This concept, originally coined by British mathematician Richard L.S. Talyor in his 1992 publication Paraterraforming – The worldhouse concept, could be used to terraform sections of several planets that are otherwise inhospitable, or cannot be altered in whole.

Potential Sites:

Within the Solar System, several possible locations exist that could be well-suited to terraforming. Consider the fact that besides Earth, Venus and Mars also lie within the Sun’s Habitable Zone (aka. “Goldilocks Zone”). However, owing to Venus’ runaway greenhouse effect, and Mars’ lack of a magnetosphere, their atmospheres are either too thick and hot or too thin and cold, to sustain life as we know it. However, this could theoretically be altered through the right kind of ecological engineering.

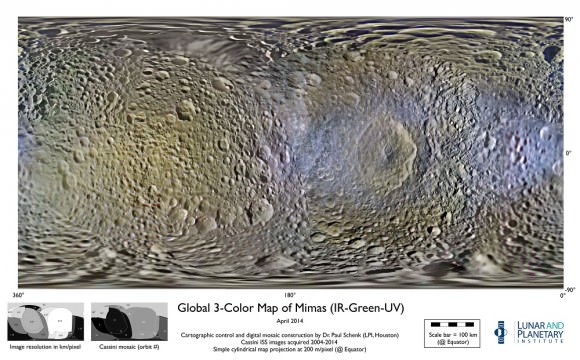

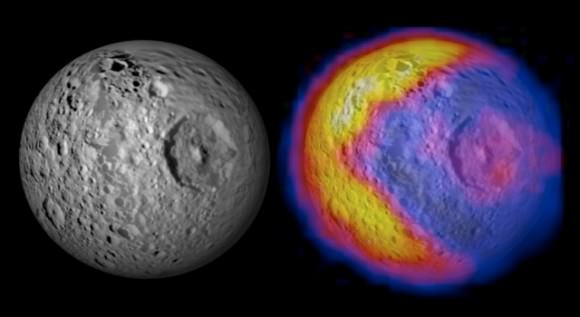

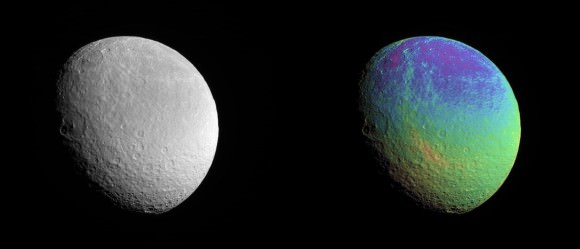

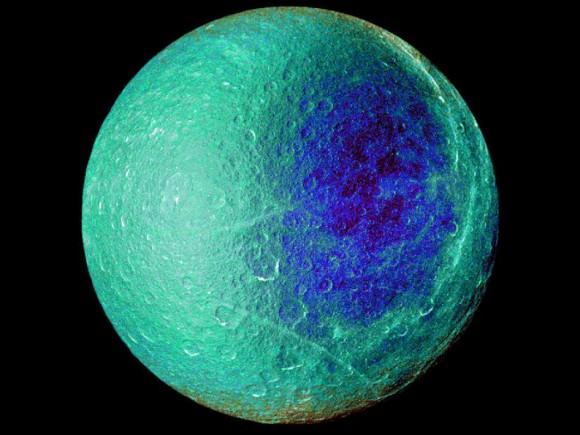

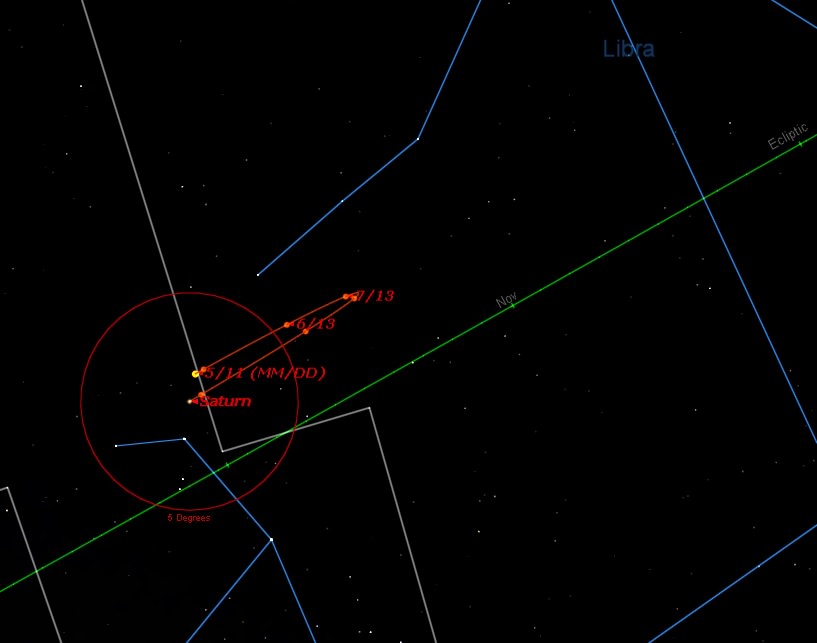

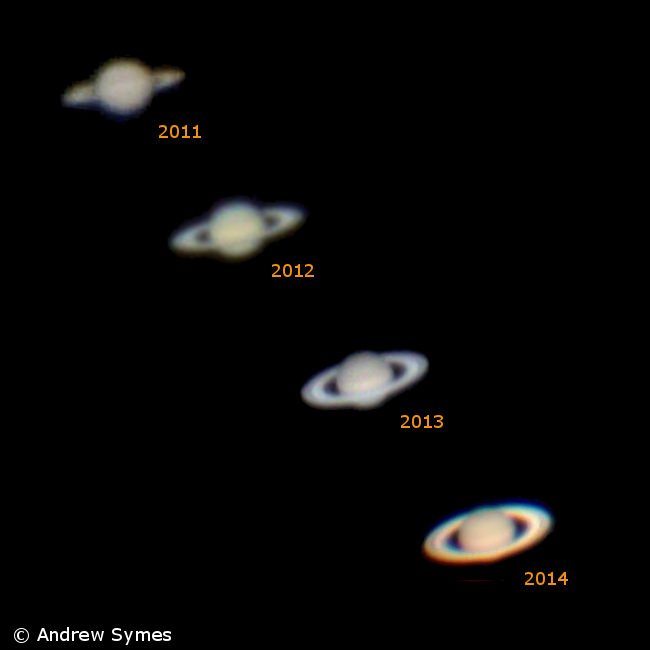

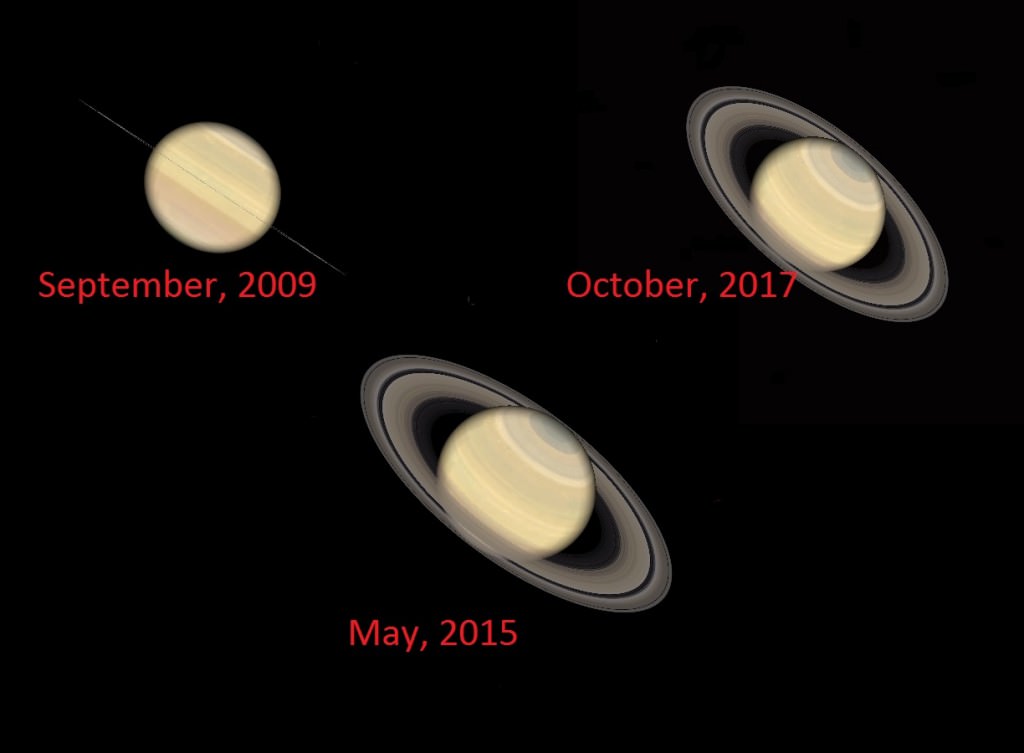

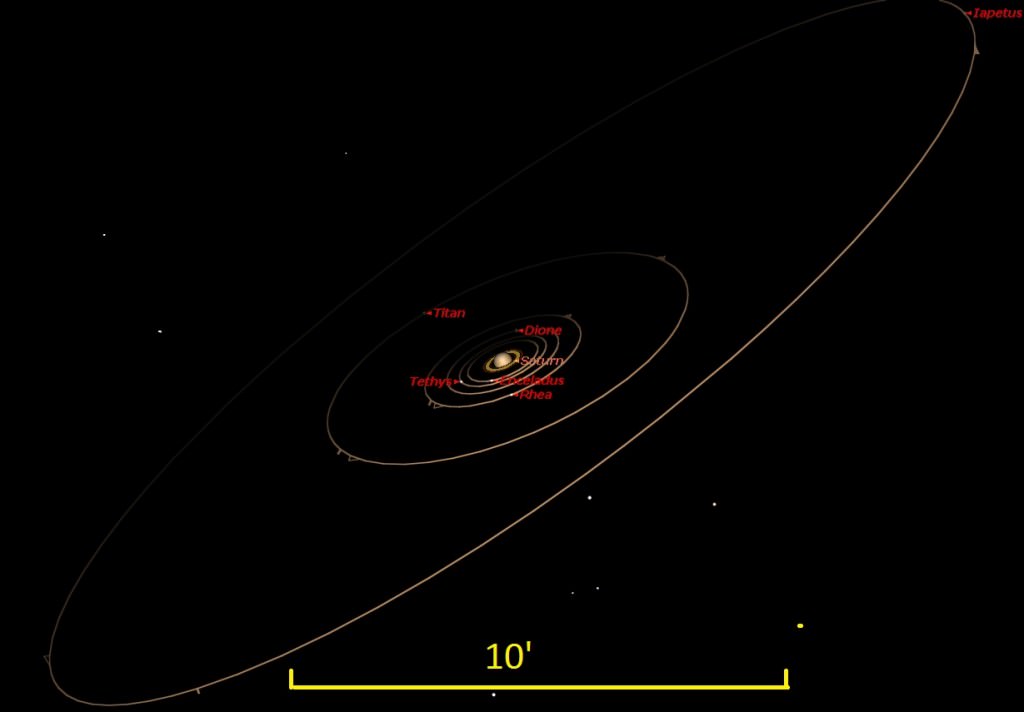

Other potential sites in the Solar System include some of the moons that orbit the gas giants. Several Jovian (i.e. in orbit of Jupiter) and Cronian (in orbit of Saturn) moons have an abundance of water ice, and scientists have speculated that if the surface temperatures were increased, viable atmospheres could be created through electrolysis and the introduction of buffer gases.

There is even speculation that Mercury and the Moon (or at least parts thereof) could be terraformed in order to be suitable for human settlement. In these cases, terraforming would require not only altering the surface but perhaps also adjusting their rotation. In the end, each case presents its own share of advantages, challenges, and likelihoods for success. Let’s consider them in order of distance from the Sun.

Inner Solar System:

The terrestrial planets of our Solar System present the best possibilities for terraforming. Not only are they located closer to our Sun, and thus in a better position to absorb its energy, but they are also rich in silicates and minerals – which any future colonies will need to grow food and build settlements. And as already mentioned, two of these planets (Venus and Mars) skirt the inner and outer edge of the Sun’s habitable zone.

Mercury:

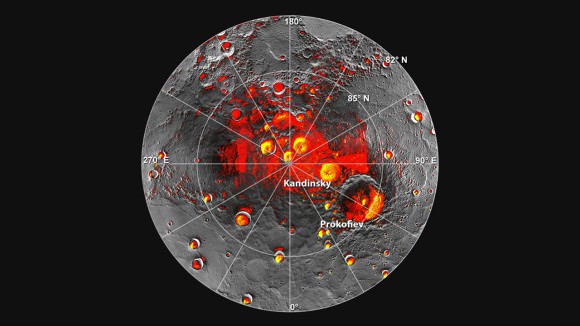

The vast majority of Mercury’s surface is hostile to life, where temperatures gravitate between extremely hot and cold – i.e. 700 K (427 °C; 800 °F) 100 K (-173 °C; -280 °F). This is due to its proximity to the Sun, the almost total lack of an atmosphere, and its very slow rotation. However, at the poles, temperatures are consistently low -93 °C (-135 °F) due to it being permanently shadowed.

The presence of water ice and organic molecules in the northern polar region has also been confirmed thanks to data obtained by the MESSENGER mission. Colonies could therefore be constructed in the regions, and limited terraforming (aka. paraterraforming) could take place. For example, if domes (or a single dome) of sufficient size could be built over the Kandinsky, Prokofiev, Tolkien, and Tryggvadottir craters, the northern region could be altered for human habitation.

Theoretically, this could be done by using mirrors to redirect sunlight into the domes which would gradually raise the temperature. The water ice would then melt, and when combined with organic molecules and finely ground sand, soil could be made. Plants could then be grown to produce oxygen, which combined with nitrogen gas, would produce a breathable atmosphere.

Venus:

As “Earth’s Twin“, there are many possibilities and advantages to terraforming Venus. The first to propose this was Sagan with his 1961 article in Science. However, subsequent discoveries – such as the high concentrations of sulfuric acid in Venus’ clouds – made this idea unfeasible. Even if algae could survive in such an atmosphere, converting the extremely dense clouds of CO² into oxygen would result in an over-dense oxygen environment.

In addition, graphite would become a by-product of the chemical reactions, which would likely form into a thick powder on the surface. This would become CO² again through combustion, thus restarting the entire greenhouse effect. However, more recent proposals have been made that advocate using carbon sequestration techniques, which are arguably much more practical.

In these scenarios, chemical reactions would be relied on to convert Venus’ atmosphere to something breathable while also reducing its density. In one scenario, hydrogen and iron aerosol would be introduced to convert the CO² in the atmosphere into graphite and water. This water would then fall to the surface, where it will cover roughly 80% of the planet – due to Venus having little variation in elevation.

Another scenario calls for the introduction of vast amounts of calcium and magnesium into the atmosphere. This would sequester carbon in the form of calcium and magnesium carbonates. An advantage to this plan is that Venus already has deposits of both minerals in its mantle, which could then be exposed to the atmosphere through drilling. However, most of the minerals would have to come from off-world in order to reduce the temperature and pressure to sustainable levels.

Yet another proposal is to freeze the atmospheric carbon dioxide down to the point of liquefaction – where it forms dry ice – and letting it accumulate on the surface. Once there, it could be buried and would remain in a solid state due to pressure, and even mined for local and off-world use. And then there is the possibility of bombarding the surface with icy comets (which could be mined from one of Jupiter’s or Saturn’s moons) to create a liquid ocean on the surface, which would sequester carbon and aid in any other of the above processes.

Last, there is the scenario in which Venus’ dense atmosphere could be removed. This could be characterized as the most direct approach to thinning an atmosphere that is far too dense for human occupation. By colliding large comets or asteroids into the surface, some of the dense CO² clouds could be blasted into space, thus leaving less atmosphere to be converted.

A slower method could be achieved using mass drivers (aka. electromagnetic catapults) or space elevators, which would gradually scoop up the atmosphere and either lift it into space or fire it away from the surface. And beyond altering or removing the atmosphere, there are also concepts that call for reducing the heat and pressure by either limiting sunlight (i.e. with solar shades) or altering the planet’s rotational velocity.

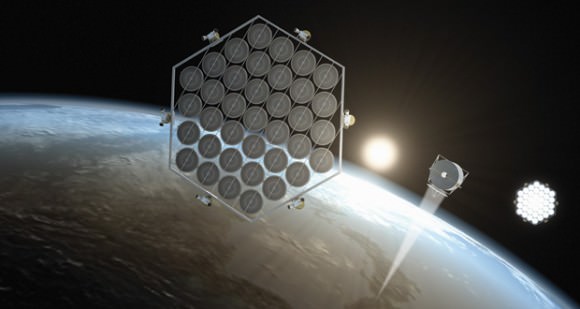

The concept of solar shades involves using either a series of small spacecraft or a single large lens to divert sunlight from a planet’s surface, thus reducing global temperatures. For Venus, which absorbs twice as much sunlight as Earth, solar radiation is believed to have played a major role in the runaway greenhouse effect that has made it what it is today.

Such a shade could be space-based, located in the Sun-Venus L1 Lagrangian Point, where it would not only prevent some sunlight from reaching Venus but also serve to reduce the amount of radiation Venus is exposed to. Alternately, solar shades or reflectors could be placed in the atmosphere or on the surface. This could consist of large reflective balloons, sheets of carbon nanotubes or graphene, or low-albedo material.

Placing shades or reflectors in the atmosphere offers two advantages: for one, atmospheric reflectors could be built in-situ, using locally-sourced carbon. Second, Venus’ atmosphere is dense enough that such structures could easily float atop the clouds. However, the amount of material would have to be large and would have to remain in place long after the atmosphere had been modified. Also, since Venus already has highly reflective clouds, any approach would have to significantly surpass its current albedo (0.65) to make a difference.

Also, the idea of speeding up Venus’ rotation has been floating around as a possible means of terraforming. If Venus could be spun-up to the point where its diurnal (day-night) cycle is similar to Earth’s, the planet might just begin to generate a stronger magnetic field. This would have the effect of reducing the amount of solar wind (and hence radiation) from reaching the surface, thus making it safer for terrestrial organisms.

The Moon:

As Earth’s closest celestial body, colonizing the Moon would be comparatively easy compared to other bodies. But when it comes to terraforming the Moon, the possibilities and challenges closely resemble those of Mercury. For starters, the Moon has an atmosphere that is so thin that it can only be referred to as an exosphere. What’s more, the volatile elements that are necessary for life are in short supply (i.e. hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon).

These problems could be addressed by capturing comets that contain water ices and volatiles and crashing them into the surface. The comets would sublimate, dispersing these gases and water vapor to create an atmosphere. These impacts would also liberate water that is contained in the lunar regolith, which could eventually accumulate on the surface to form natural bodies of water.

The transfer of momentum from these comets would also get the Moon rotating more rapidly, speeding up its rotation so that it would no longer be tidally locked. A Moon that was sped up to rotate once on its axis every 24 hours would have a steady diurnal cycle, which would make colonization and adapting to life on the Moon easier.

There is also the possibility of paraterraforming parts of the Moon in a way that would be similar to terraforming Mercury’s polar region. In the Moon’s case, this would take place in the Shackleton Crater, where scientists have already found evidence of water ice. Using solar mirrors and a dome, this crater could be turned into a micro-climate where plants could be grown and a breathable atmosphere created.

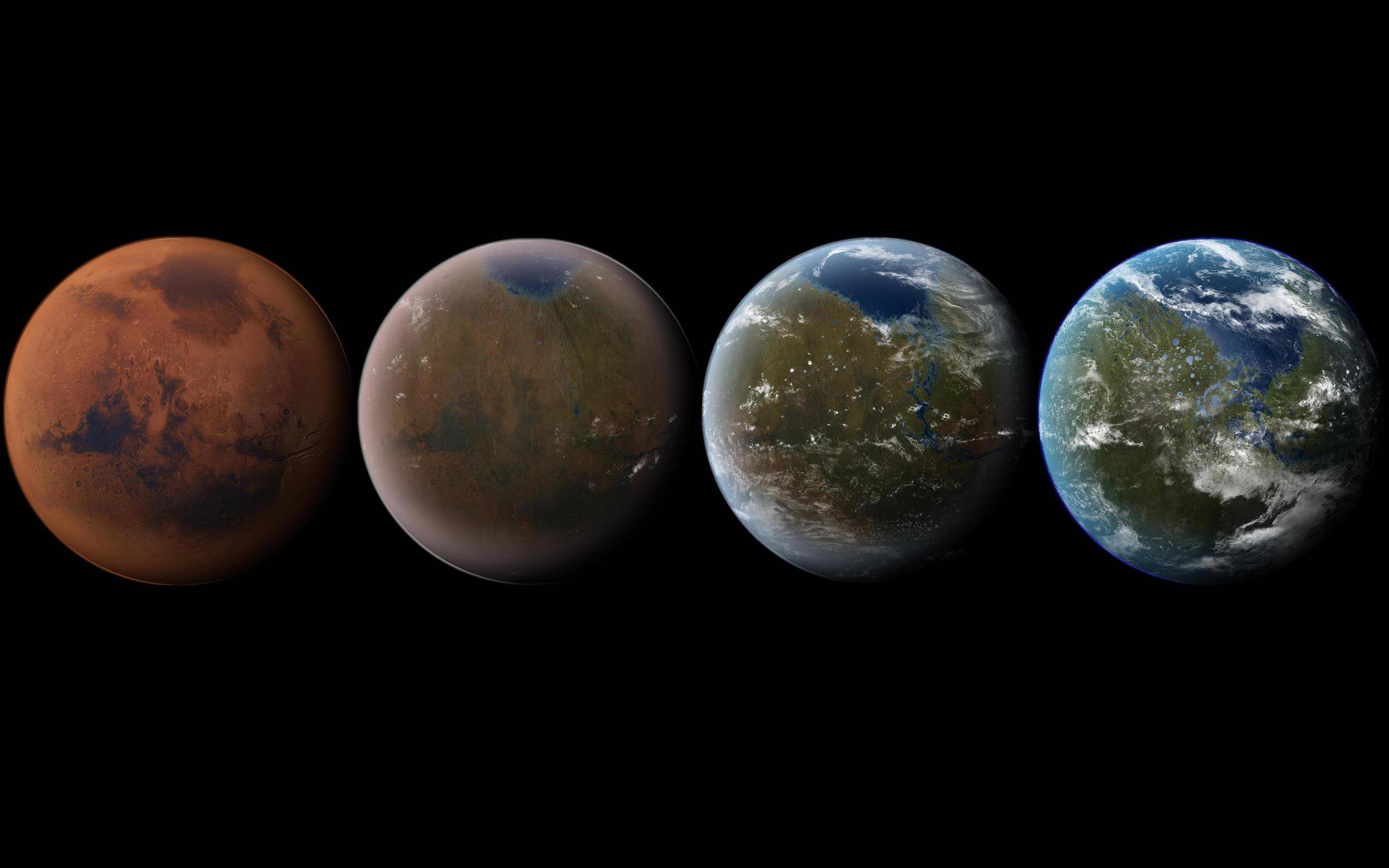

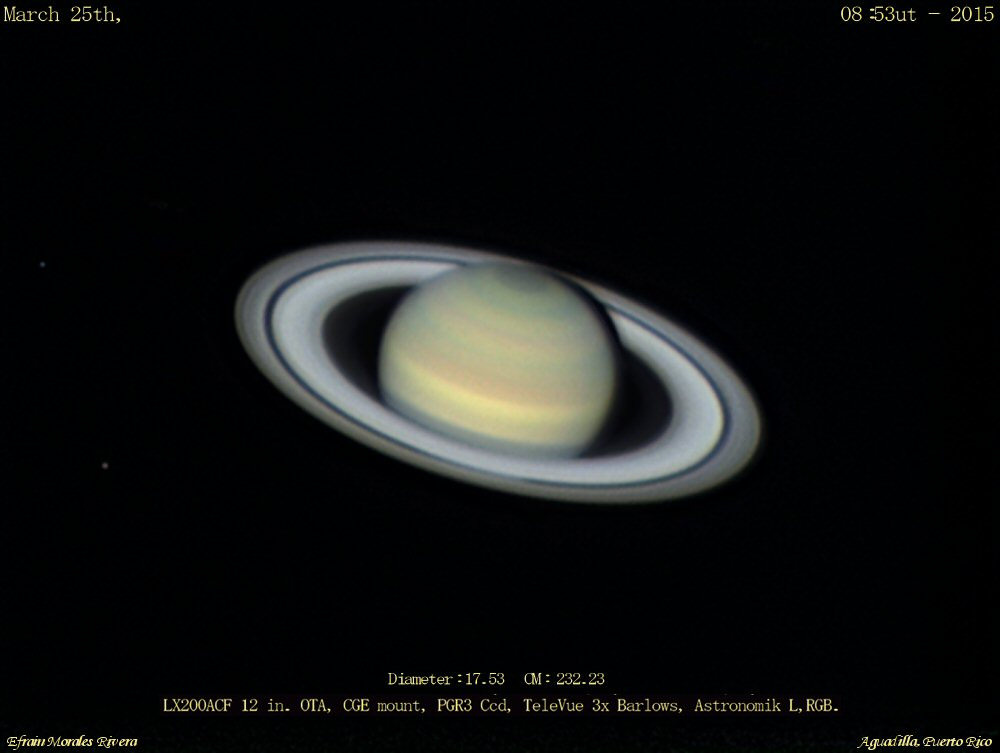

Mars:

When it comes to terraforming, Mars is the most popular destination. There are several reasons for this, ranging from its proximity to Earth, its similarities to Earth, and the fact that it once had an environment that was very similar to Earth’s – which included a thicker atmosphere and the presence of warm, flowing water on the surface. Lastly, it is currently believed that Mars may have additional sources of water beneath its surface.

In brief, Mars has a diurnal and seasonal cycle that are very close to what we experience here on Earth. In the former case, a single day on Mars lasts 24 hours and 40 minutes. In the latter case, and owing to Mars’ similarly-tilted axis (25.19° compared to Earth’s 23°), Mars experiences seasonal changes that are very similar to Earth’s. Though a single season on Mars lasts roughly twice as long, the temperature variation that results is very similar – ±178 °C (320°F) compared to Earth’s ±160 °C (278°F).

Beyond these, Mars would need to undergo vast transformations in order for human beings to live on its surface. The atmosphere would need to be thickened drastically, and its composition would need to be changed. Currently, Mars’ atmosphere is composed of 96% carbon dioxide, 1.93% argon, and 1.89% nitrogen, and the air pressure is equivalent to only 1% of Earth’s at sea level.

Above all, Mars lacks a magnetosphere, which means that its surface receives significantly more radiation than we are used to here on Earth. In addition, it is believed that Mars once had a magnetosphere and that the disappearance of this magnetic field led to the stripping of Mars’ atmosphere by solar wind. This in turn is what led Mars to become the cold, desiccated place it is today.

Ultimately, this means that in order for the planet to become habitable by human standards, its atmosphere would need to be significantly thickened and the planet significantly warmed. The composition of the atmosphere would need to change as well, from the current CO²-heavy mix to a nitrogen-oxygen balance of about 70/30. And above all, the atmosphere would need to be replenished every so often to compensate for the loss.

Luckily, the first three requirements are largely complementary, and present a wide range of possible solutions. For starters, Mars’ atmosphere could be thickened and the planet warmed by bombarding its polar regions with meteors. These would cause the poles to melt, releasing their deposits of frozen carbon dioxide and water into the atmosphere and triggering a greenhouse effect.

The introduction of volatile elements, such as ammonia and methane, would also help to thicken the atmosphere and trigger warming. Both could be mined from the icy moons of the outer Solar System, particularly from the moons of Ganymede, Callisto, and Titan. These could also be delivered to the surface via meteoric impacts.

After impacting on the surface, the ammonia ice would sublimate and break down into hydrogen and nitrogen – the hydrogen interacting with the CO² to form water and graphite, while the nitrogen acts as a buffer gas. The methane, meanwhile, would act as a greenhouse gas that would further enhance global warming. In addition, the impacts would throw tons of dust into the air, further fueling the warming trend.

In time, Mars’ ample supplies of water ice – which can be found not only in the poles but in vast subsurface deposits of permafrost – would all sublimate to form warm, flowing water. And with significantly increased air pressure and a warmer atmosphere, humans might be able to venture out onto the surface without the need for pressure suits.

However, the atmosphere will still need to be converted into something breathable. This will be far more time-consuming, as the process of converting the atmospheric CO² into oxygen gas will likely take centuries. In any case, several possibilities have been suggested, which include converting the atmosphere through photosynthesis – either with cyanobacteria or Earth plants and lichens.

Other suggestions include building orbital mirrors, which would be placed near the poles and direct sunlight onto the surface to trigger a cycle of warming by causing the polar ice caps to melt and release their CO² gas. Using dark dust from Phobos and Deimos to reduce the surface’s albedo, thus allowing it to absorb more sunlight, has also been suggested.

In short, there are plenty of options for terraforming Mars. And many of them, if not being readily available, are at least on the table…

Outer Solar System:

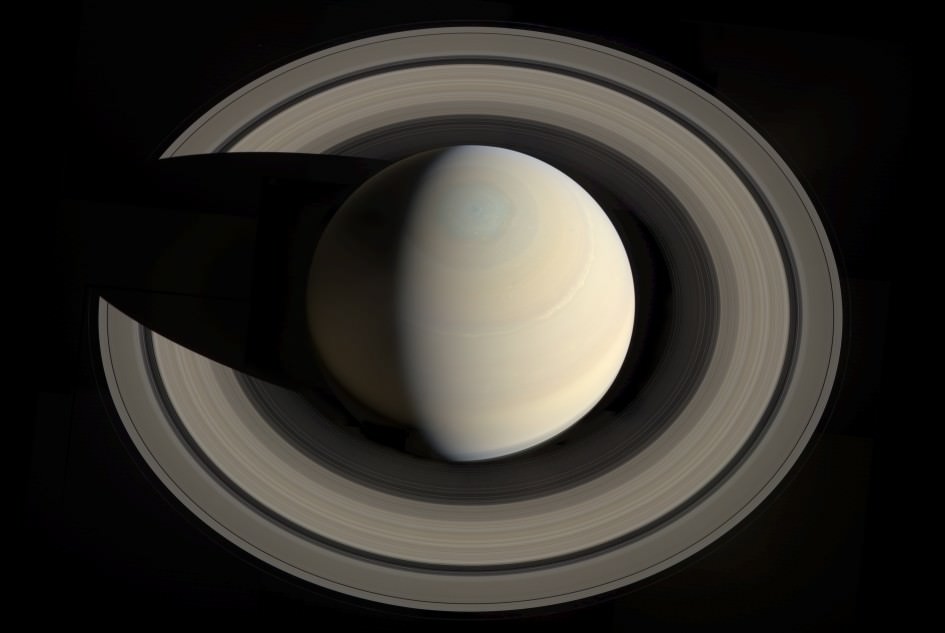

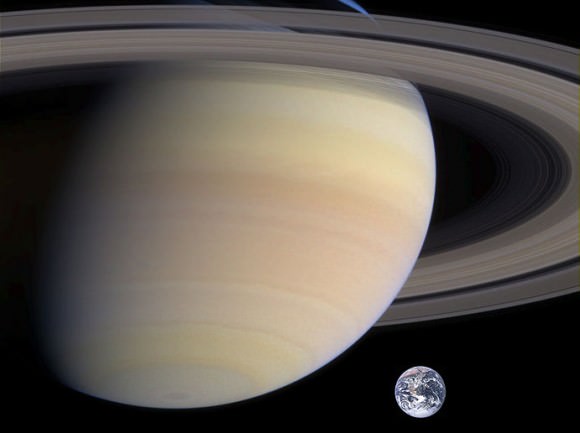

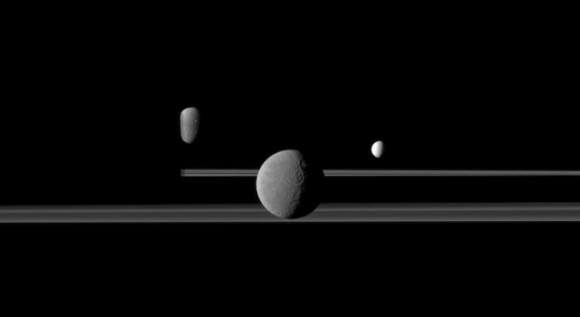

Beyond the Inner Solar System, there are several sites that would make for good terraforming targets as well. Particularly around Jupiter and Saturn, there are several sizable moons – some of which are larger than Mercury – that have an abundance of water in the form of ice (and in some cases, maybe even interior oceans).

At the same time, many of these same moons contain other necessary ingredients for functioning ecosystems, such as frozen volatiles – like ammonia and methane. Because of this, and as part of our ongoing desire to explore farther out into our Solar System, many proposals have been made to seed these moons with bases and research stations. Some plans even include possible terraforming to make them suitable for long-term habitation.

The Jovian Moons:

Jupiter’s largest moons, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – known as the Galileans, after their founder (Galileo Galilei) – have long been the subject of scientific interest. For decades, scientists have speculated about the possible existence of a subsurface ocean on Europa, based on theories about the planet’s tidal heating (a consequence of its eccentric orbit and orbital resonance with the other moons).

Analysis of images provided by the Voyager 1 and Galileo probes added weight to this theory, showing regions where it appeared that the subsurface ocean had melted through. What’s more, the presence of this warm water ocean has also led to speculation about the existence of life beneath Europa’s icy crust – possibly around hydrothermal vents at the core-mantle boundary.

Because of this potential for habitability, Europa has also been suggested as a possible site for terraforming. As the argument goes, if the surface temperature could be increased, and the surface ice melted, the entire planet could become an ocean world. Sublimation of the ice, which would release water vapor and gaseous volatiles, would then be subject to electrolysis (which already produces a thin oxygen atmosphere).

However, Europa has no magnetosphere of its own and lies within Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field. As a result, its surface is exposed to significant amounts of radiation – 540 rem of radiation per day compared to about 0.0030 rem per year here on Earth – and any atmosphere we create would begin to be stripped away by Jupiter. Ergo, radiation shielding would need to be put in place that could deflect the majority of this radiation.

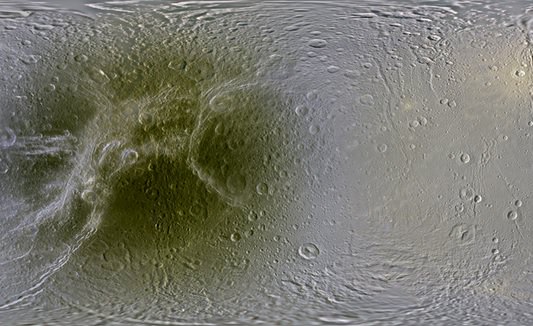

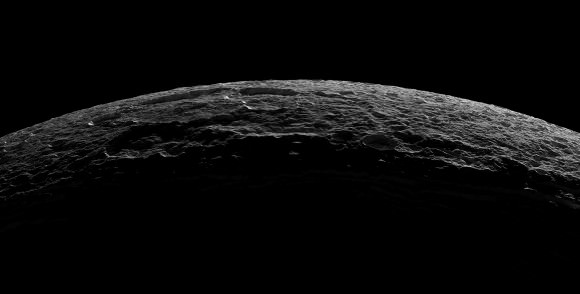

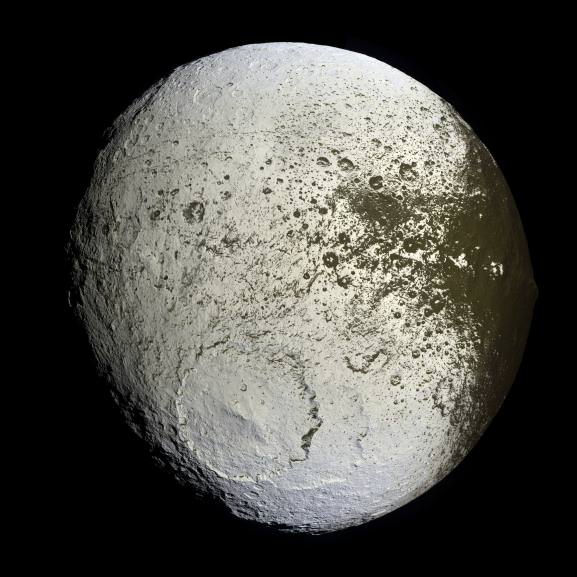

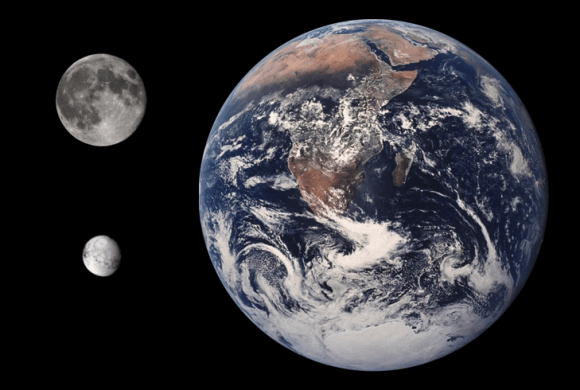

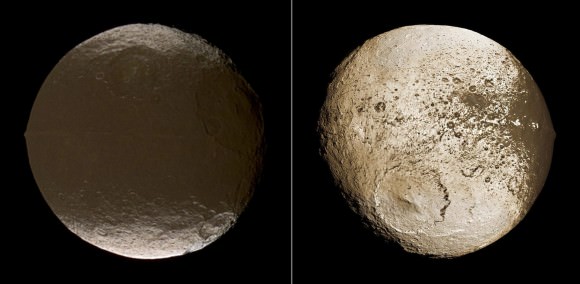

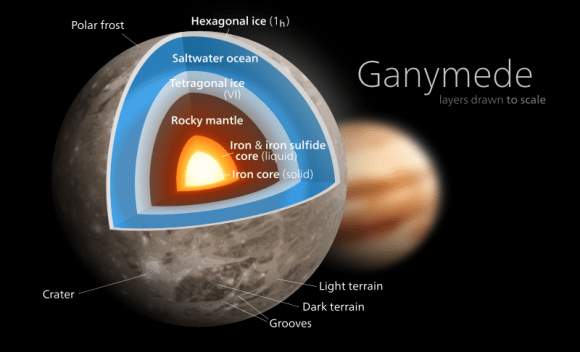

And then there is Ganymede, the third most-distant of Jupiter’s Galilean moons. Much like Europa, it is a potential site of terraforming and presents numerous advantages. For one, it is the largest moon in our Solar System, larger than our own moon and even larger than the planet Mercury. In addition, it also has ample supplies of water ice, is believed to have an interior ocean, and even has its own magnetosphere.

Hence, if the surface temperature were increased and the ice sublimated, Ganymede’s atmosphere could be thickened. Like Europa, it would also become an ocean planet, and its own magnetosphere would allow for it to hold on to more of its atmosphere. However, Jupiter’s magnetic field still exerts a powerful influence over the planet, which means radiation shields would still be needed.

Lastly, there is Callisto, the fourth-most distant of the Galileans. Here too, abundant supplies of water ice, volatiles, and the possibility of an interior ocean all point towards the potential for habitability. But in Callisto’s case, there is the added bonus of it being beyond Jupiter’s magnetic field, which reduces the threat of radiation and atmospheric loss.

The process would begin with surface heating, which would sublimate the water ice and Callisto’s supplies of frozen ammonia. From these oceans, electrolysis would lead to the formation of an oxygen-rich atmosphere, and the ammonia could be converted into nitrogen to act as a buffer gas. However, since the majority of Callisto is ice, it would mean that the planet would lose considerable mass and have no continents. Again, an ocean planet would result, necessitating floating cities or massive colony ships.

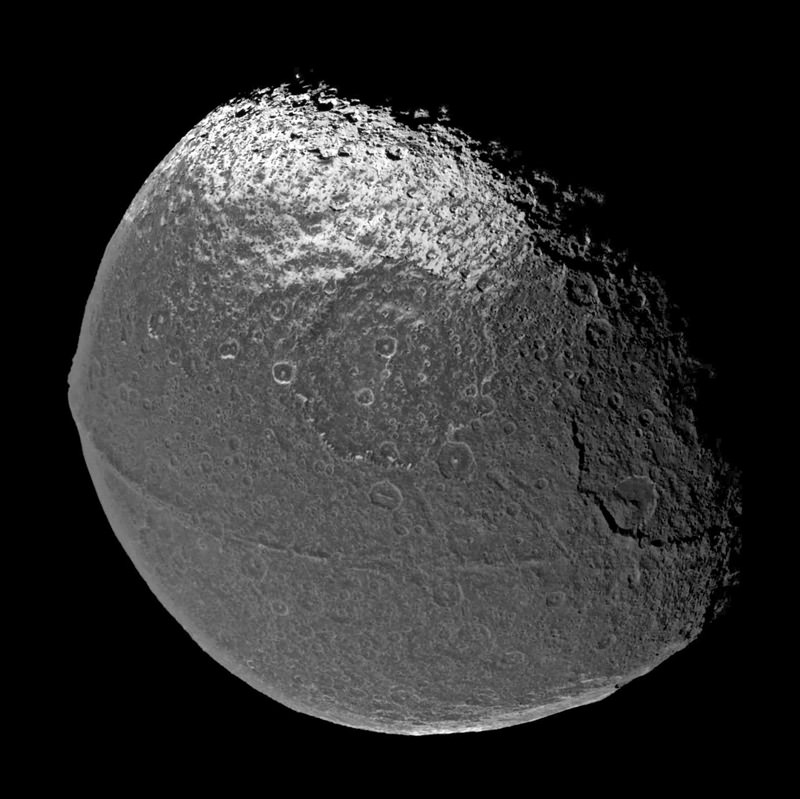

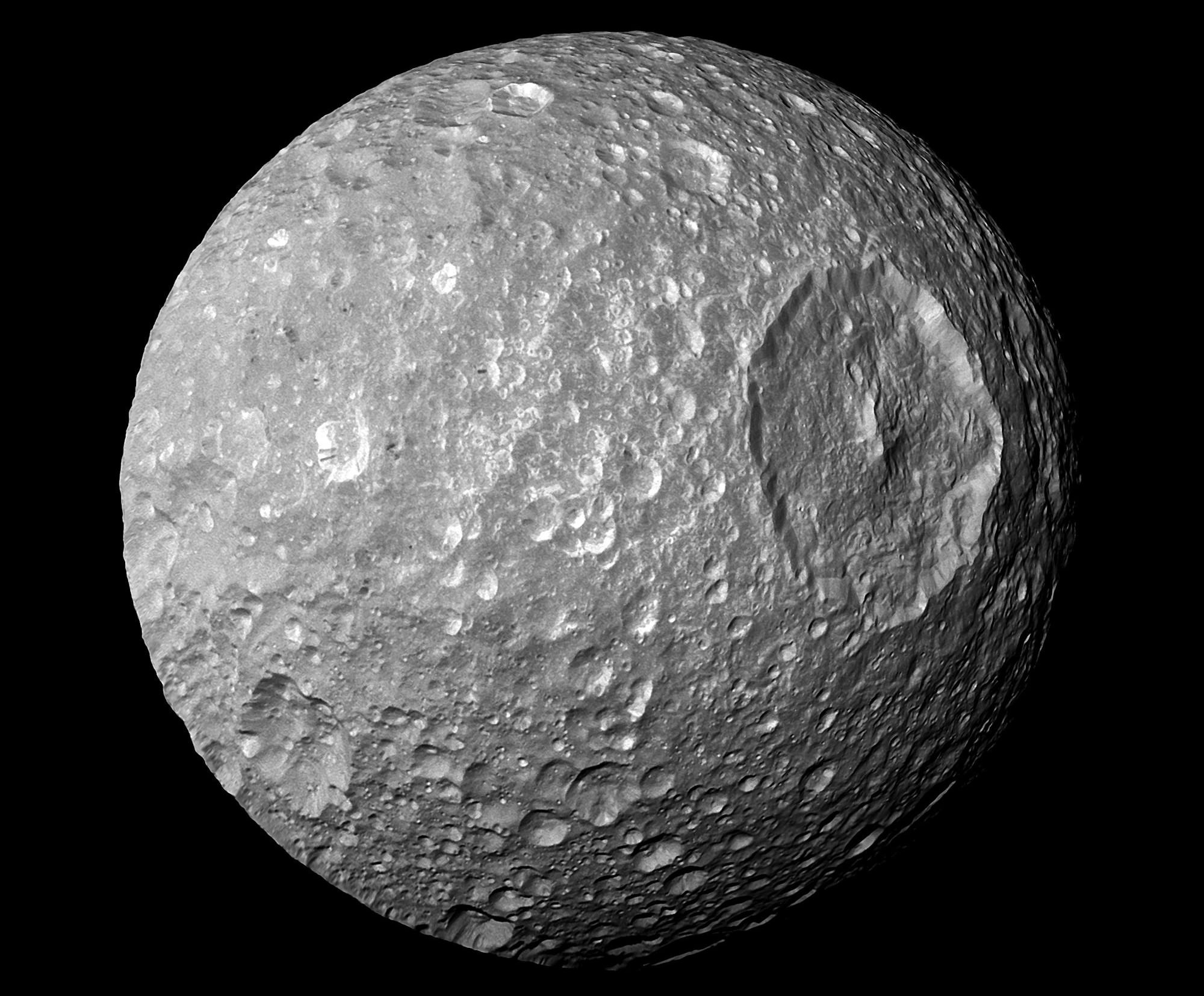

The Cronians Moons:

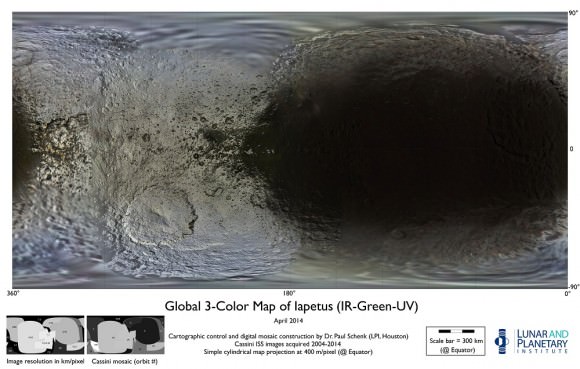

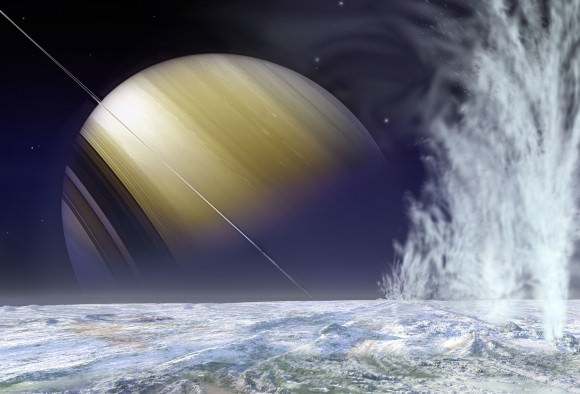

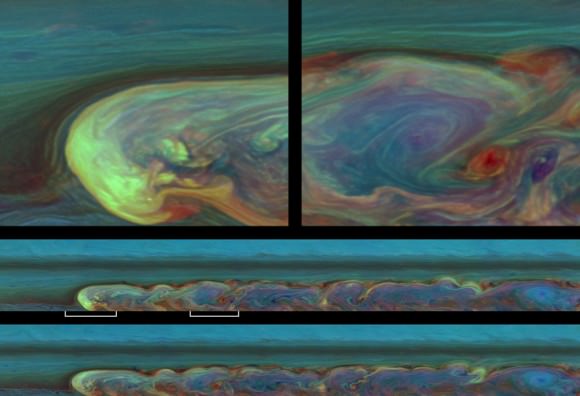

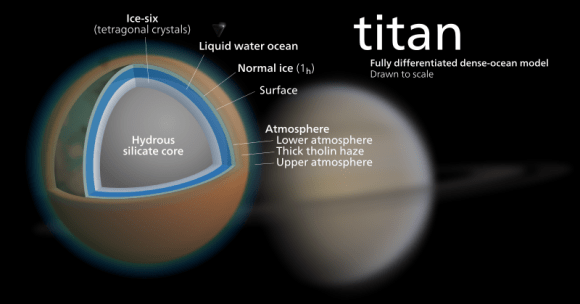

Much like the Jovian Moons, Saturn’s Moons (also known as the Cronian) present opportunities for terraforming. Again, this is due to the presence of water ice, interior oceans, and volatile elements. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, also has an abundance of methane that comes in liquid form (the methane lakes around its northern polar region) and in gaseous form in its atmosphere. Large caches of ammonia are also believed to exist beneath the surface ice.

Titan is also the only natural satellite to have a dense atmosphere (one and half times the pressure of Earth’s) and the only planet outside of Earth where the atmosphere is nitrogen-rich. Such a thick atmosphere would mean that it would be far easier to equalize pressure for habitats on the planet. What’s more, scientists believe this atmosphere is a prebiotic environment rich in organic chemistry – i.e. similar to Earth’s early atmosphere (only much colder).

As such, converting it to something Earth-like would be feasible. First, the surface temperature would need to be increased. Since Titan is very distant from the Sun and already has an abundance of greenhouse gases, this could only be accomplished through orbital mirrors. This would sublimate the surface ice, releasing ammonia beneath, which would lead to more heating.

The next step would involve converting the atmosphere to something breathable. As already noted, Titan’s atmosphere is nitrogen-rich, which would remove the need for introducing a buffer gas. And with the availability of water, oxygen could be introduced by generating it through electrolysis. At the same time, the methane and other hydrocarbons would have to be sequestered, in order to prevent an explosive mixture with the oxygen.

But given the thickness and multi-layered nature of Titan’s ice, which is estimated to account for half of its mass, the moon would be very much an ocean planet- i.e. with no continents or landmasses to build on. So once again, any habitats would have to take the form of either floating platforms or large ships.

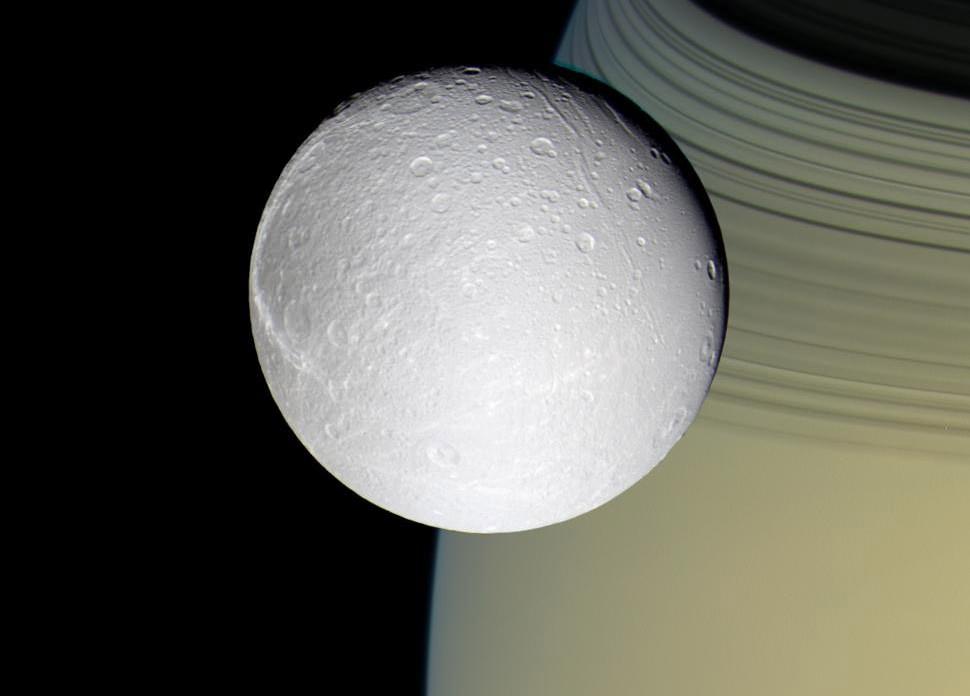

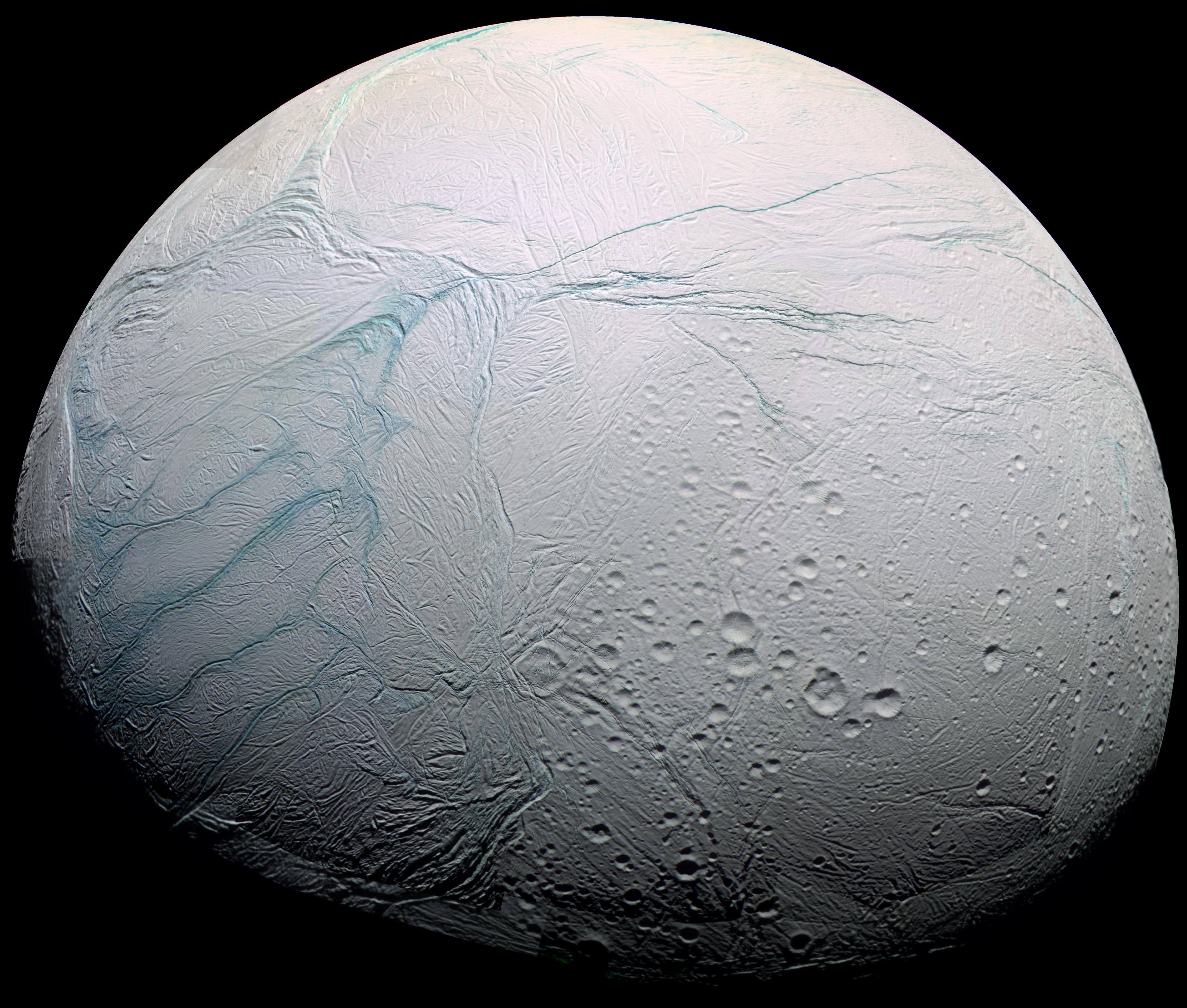

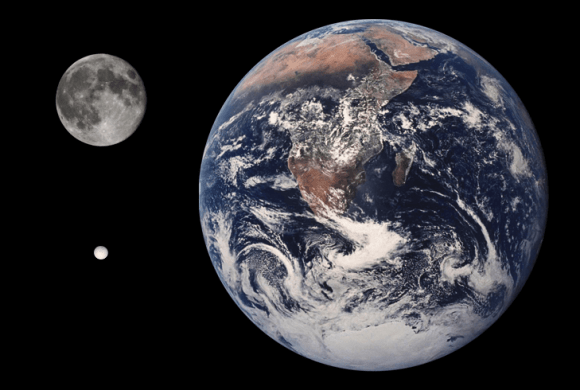

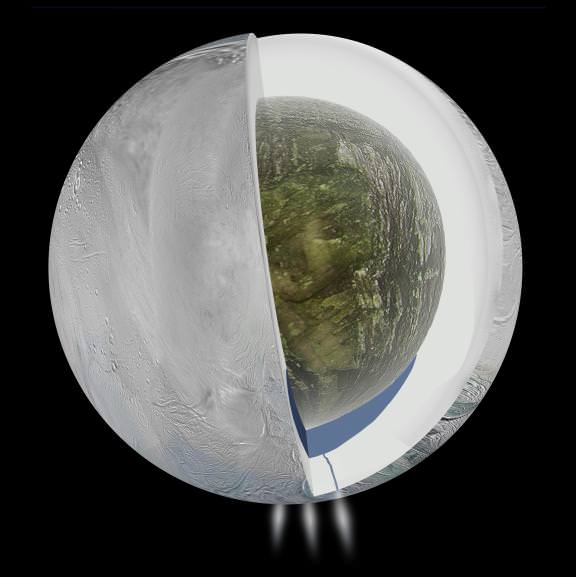

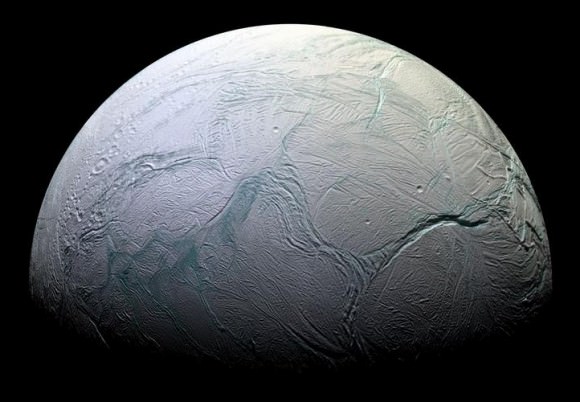

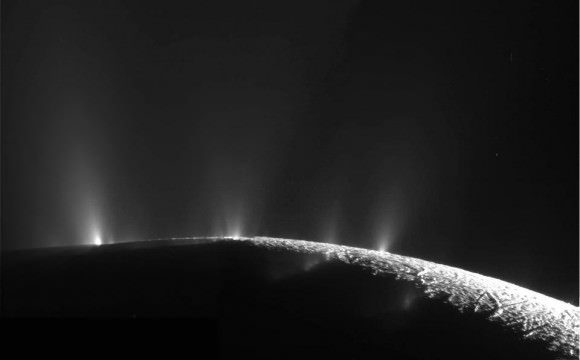

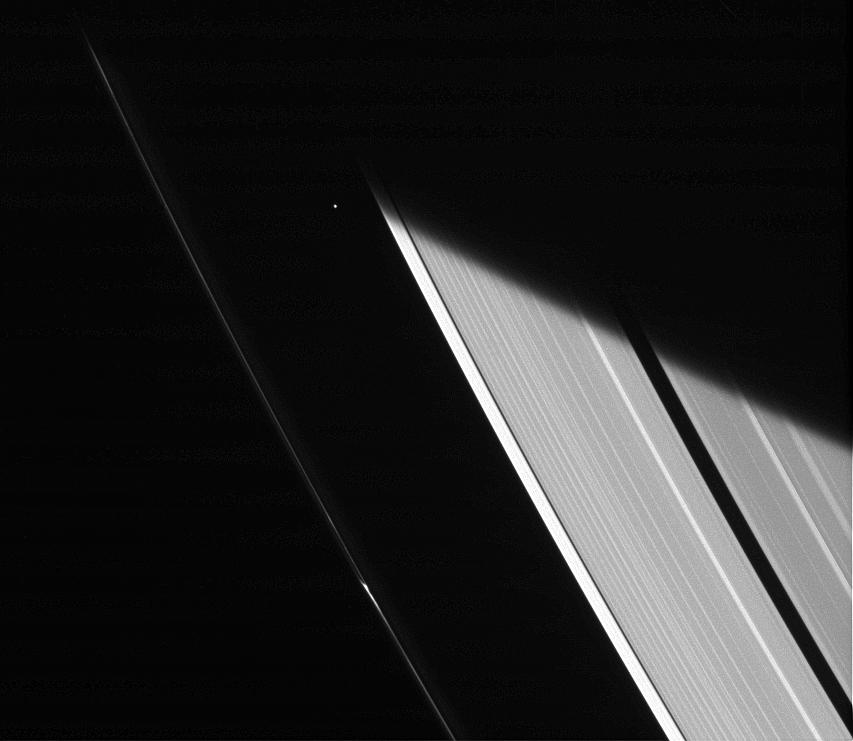

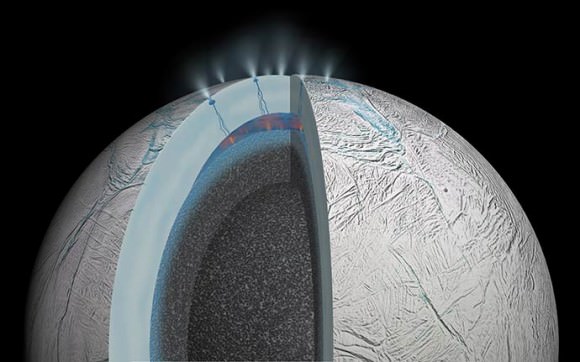

Enceladus is another possibility, thanks to the recent discovery of a subsurface ocean. Analysis by the Cassini space probe of the water plumes erupting from its southern polar region also indicated the presence of organic molecules. As such, terraforming it would be similar to terraforming Jupiter’s moon of Europa, and would yield a similar ocean moon.

Again, this would likely have to involve orbital mirrors, given Enceladus’ distance from our Sun. Once the ice began to sublimate, electrolysis would generate oxygen gas. The presence of ammonia in the subsurface ocean would also be released, helping to raise the temperature and serving as a source of nitrogen gas, with which to buffer the atmosphere.

Exoplanets:

In addition to the Solar System, extra-solar planets (aka. exoplanets) are also potential sites for terraforming. Of the 1,941 confirmed exoplanets discovered so far, these planets are those that have been designated “Earth-like. In other words, they are terrestrial planets that have atmospheres and, like Earth, occupy the region around a star where the average surface temperature allows for liquid water (aka. habitable zone).

The first planet confirmed by Kepler to have an average orbital distance that placed it within its star’s habitable zone was Kepler-22b. This planet is located about 600 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Cygnus, was first observed on May 12th, 2009, and then confirmed on Dec 5th, 2011. Based on all the data obtained, scientists believe that this world is roughly 2.4 times the radius of Earth, and is likely covered in oceans or has a liquid or gaseous outer shell.

In addition, there are star systems with multiple “Earth-like” planets occupying their habitable zones. Gliese 581 is a good example, a red dwarf star that is located 20.22 light-years away from Earth in the Libra constellation. Here, three confirmed and two possible planets exist, two of which are believed to orbit within the star’s habitable zone. These include the confirmed planet Gliese 581 d and the hypothetical Gliese 581 g.

Tau Ceti is another example. This G-class star, which is located roughly 12 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cetus, has five possible planets orbiting it. Two of these are Super-Earths that are believed to orbit the star’s habitable zone – Tau Ceti e and Tau Ceti f. However, Tau Ceti e is believed to be too close for anything other than Venus-like conditions to exist on its surface.

In all cases, terraforming the atmospheres of these planets would most likely involve the same techniques used to terraform Venus and Mars, though to varying degrees. For those located on the outer edge of their habitable zones, terraforming could be accomplished by introducing greenhouse gases or covering the surface with low albedo material to trigger global warming. On the other end, solar shades and carbon sequestering techniques could reduce temperatures to the point where the planet is considered hospitable.

Potential Benefits:

When addressing the issue of terraforming, there is the inevitable question – “why should we?” Given the expenditure in resources, the time involved, and other challenges that naturally arise (see below), what reasons are there to engage in terraforming? As already mentioned, there are the reasons cited by Musk, about the need to have a “backup location” to prevent any particular cataclysm from claiming all of humanity.

Putting aside for the moment the prospect of a nuclear holocaust, there is also the likelihood that life will become untenable on certain parts of our planet in the coming century. As the NOAA reported in March of 2015, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have now surpassed 400 ppm, a level not seen since the Pliocene Era – when global temperatures and sea levels were significantly higher.

And as a series of scenarios computed by NASA show, this trend is likely to continue until 2100, and with serious consequences. In one scenario, carbon dioxide emissions will level off at about 550 ppm toward the end of the century, resulting in an average temperature increase of 2.5 °C (4.5 °F). In the second scenario, carbon dioxide emissions rise to about 800 ppm, resulting in an average increase of about 4.5 °C (8 °F). Whereas the increases predicted in the first scenario are sustainable, in the latter scenario, life will become untenable on many parts of the planet.

As a result of this, creating a long-term home for humanity on Mars, the Moon, Venus, or elsewhere in the Solar System may be necessary. In addition to offering us other locations from which to extract resources, cultivate food, and as a possible outlet for population pressures, having colonies on other worlds could mean the difference between long-term survival and extinction.

There is also the argument that humanity is already well-versed in altering planetary environments. For centuries, humanity’s reliance on industrial machinery, coal, and fossil fuels has had a measurable effect on Earth’s environment. And whereas the Greenhouse Effect that we have triggered here was not deliberate, our experience and knowledge in creating it here on Earth could be put to good use on planets where surface temperatures need to be raised artificially.

In addition, it has also been argued that working with environments where there is a runaway Greenhouse Effect – i.e. Venus – could yield valuable knowledge that could in turn be used here on Earth. Whether it is the use of extreme bacteria, introducing new gases, or mineral elements to sequester carbon, testing these methods out on Venus could help us to combat Climate Change here at home.

It has also been argued that Mars’ similarities to Earth are a good reason to terraform it. Essentially, Mars once resembled Earth, until its atmosphere was stripped away, causing it to lose virtually all the liquid water on its surface. Ergo, terraforming it would be tantamount to returning it to its once-warm and watery glory. The same argument could be made of Venus, where efforts to alter it would restore it to what it was before a runaway Greenhouse Effect turned it into the harsh, extremely hot world it is today.

Last, but not least, there is the argument that colonizing the Solar System could usher in an age of “post-scarcity”. If humanity were to build outposts and based on other worlds, mine the asteroid belt, and harvest the resources of the Outer Solar System, we would effectively have enough minerals, gases, energy, and water resources to last us indefinitely. It could also help trigger a massive acceleration in human development, defined by leaps and bounds in technological and social progress.

Potential Challenges:

When it comes right down to it, all of the scenarios listed above suffer from one or more of the following problems:

- They are not possible with existing technology

- They require a massive commitment of resources

- They solve one problem, only to create another

- They do not offer a significant return on the investment

- They would take a really, REALLY long time

Case in point, all of the potential ideas for terraforming Venus and Mars involve infrastructure that does not yet exist and would be very expensive to create. For instance, the orbital shade concept that would cool Venus calls for a structure that would need to be four times the diameter of Venus itself (if it were positioned at L1). It would therefore require megatons of material, all of which would have to be assembled on site.

In contrast, increasing the speed of Venus’s rotation would require energy many orders of magnitude greater than the construction of orbiting solar mirrors. As with removing Venus’ atmosphere, the process would also require a significant number of impactors that would have to be harnessed from the outer solar System – mainly from the Kuiper Belt.

In order to do this, a large fleet of spaceships would be needed to haul them, and they would need to be equipped with advanced drive systems that could make the trip in a reasonable amount of time. Currently, no such drive systems exist, and conventional methods – ranging from ion engines to chemical propellants – are neither fast or economical enough.

To illustrate, NASA’s New Horizons mission took more than 11 years to get make its historic rendezvous with Pluto in the Kuiper Belt, using conventional rockets and the gravity-assist method. Meanwhile, the Dawn mission, which relied on ionic propulsion, took almost four years to reach Vesta in the Asteroid Belt. Neither method is practical for making repeated trips to the Kuiper Belt and hauling back icy comets and asteroids, and humanity has nowhere near the number of ships we would need to do this.

The Moon’s proximity makes it an attractive option for terraforming. But again, the resources needed – which would likely include several hundred comets – would again need to be imported from the outer Solar System. And while Mercury’s resources could be harvested in-situ or brought from Earth to paraterraform its northern polar region, the concept still calls for a large fleet of ships and robot builders which do not yet exist.

The outer Solar System presents a similar problem. In order to begin terraforming these moons, we would need infrastructure between here and there, which would mean bases on the Moon, Mars, and within the Asteroid Belt. Here, ships could refuel as they transport materials to the Jovian sand Cronian systems, and resources could be harvested from all three of these locations as well as within the systems themselves.

But of course, it would take many, many generations (or even centuries) to build all of that, and at considerable cost. Ergo, any attempts at terraforming the outer Solar System would have to wait until humanity had effectively colonized the inner Solar System. And terraforming the Inner Solar System will not be possible until humanity has plenty of space hauler on hand, not to mention fast ones!

The necessity for radiation shields also presents a problem. The size and cost of manufacturing shields that could deflect Jupiter’s magnetic field would be astronomical. And while the resources could be harvested from the nearby Asteroid Belt, transporting and assembling them in space around the Jovian Moons would again require many ships and robotic workers. And again, there would have to be extensive infrastructure between Earth and the Jovian system before any of this could proceed.

As for item three, there are plenty of problems that could result from terraforming. For instance, transforming Jupiter’s and Saturn’s moons into ocean worlds could be pointless, as the volume of liquid water would constitute a major portion of the moon’s overall radius. Combined with their low surface gravities, high orbital velocities, and the tidal effects of their parent planets, this could lead to severely high waves on their surfaces. In fact, these moons could become totally unstable as a result of being altered.

There are also several questions about the ethics of terraforming. Basically, altering other planets in order to make them more suitable to human needs raises the natural question of what would happen to any lifeforms already living there. If in fact Mars and other Solar System bodies have indigenous microbial (or more complex) life, which many scientists suspect, then altering their ecology could impact or even wipe out these lifeforms. In short, future colonists and terrestrial engineers would effectively be committing genocide.

Another argument that is often made against terraforming is that any effort to alter the ecology of another planet does not present any immediate benefits. Given the cost involved, what possible incentive is there to commit so much time, resources, and energy to such a project? While the idea of utilizing the resources of the Solar System makes sense in the long run, the short-term gains are far less tangible.

Basically, harvested resources from other worlds is not economically viable when you can extract them here at home for much less. And real-estate is only the basis of an economic model if the real estate itself is desirable. While MarsOne has certainly shown us that there are plenty of human beings who are willing to make a one-way trip to Mars, turning the Red Planet, Venus, or elsewhere into a “new frontier” where people can buy up land will first require some serious advances in technology, some serious terraforming, or both.

As it stands, the environments of Mars, Venus, the Moon, and the outer Solar System are all hostile to life as we know it. Even with the requisite commitment of resources and people willing to be the “first wave”, life would be very difficult for those living out there. And this situation would not change for centuries or even millennia. Like it not, transforming a planet’s ecology is very slow, laborious work.

Conclusion:

So… after considering all of the places where humanity could colonize and terraform, what it would take to make that happen, and the difficulties in doing so, we are once again left with one important question. Why should we? Assuming that our very survival is not at stake, what possible incentives are there for humanity to become an interplanetary (or interstellar) species?

Perhaps there is no good reason. Much like sending astronauts to the Moon, taking to the skies, and climbing the highest mountain on Earth, colonizing other planets may be nothing more than something we feel we need to do. Why? Because we can! Such a reason has been good enough in the past, and it will likely be sufficient again in the not-too-distant future.

This should is no way deter us from considering the ethical implications, the sheer cost involved, or the cost-to-benefit ratio. But in time, we might find that we have no choice but to get out there, simply because Earth is just becoming too stuffy and crowded for us!

Check out the full Definitive Guide here:

- How do we Terraform Mercury?

- How Do We Terraform Venus?

- How Do We Terraform the Moon?

- How Do We Terraform Mars?

- How Do We Terraform Ceres?

- How Do We Terraform Jupiter’s Moons?

- How Do We Terraform Saturn’s Moons?

We’ve also got articles that explore the more radical side of terraforming, like Could We Terraform Jupiter?, Could We Terraform The Sun?, and Could We Terraform A Black Hole? and Student Team Wants to Terraform Mars Using Cyanobacteria.

Astronomy Cast also has good episodes on the subject, like Episode 96: Humans to Mar, Part 3 – Terraforming Mars

For more information, check out Terraforming Mars at NASA Quest! and NASA’s Journey to Mars.