You can be thankful that we bask in the glow of a relatively placid star. Currently about halfway along its 10 billion year career on the Main Sequence, our Sun fuses hydrogen into helium in a battle against gravitational collapse. This balancing act produces energy via the proton-proton chain process, which in turn, fuels the drama of life on Earth.

Looking out into the universe, we see stars that are much more brash and impulsive, such as red dwarf upstarts unleashing huge planet-sterilizing flares, and massive stars destined to live fast and die young.

Our Sun gives us the unprecedented chance to study a star up close, and our modern day technological society depends on keeping a close watch on what the Sun might do next. But did you know that some of the key mechanisms powering the solar cycle are still not completely understood?

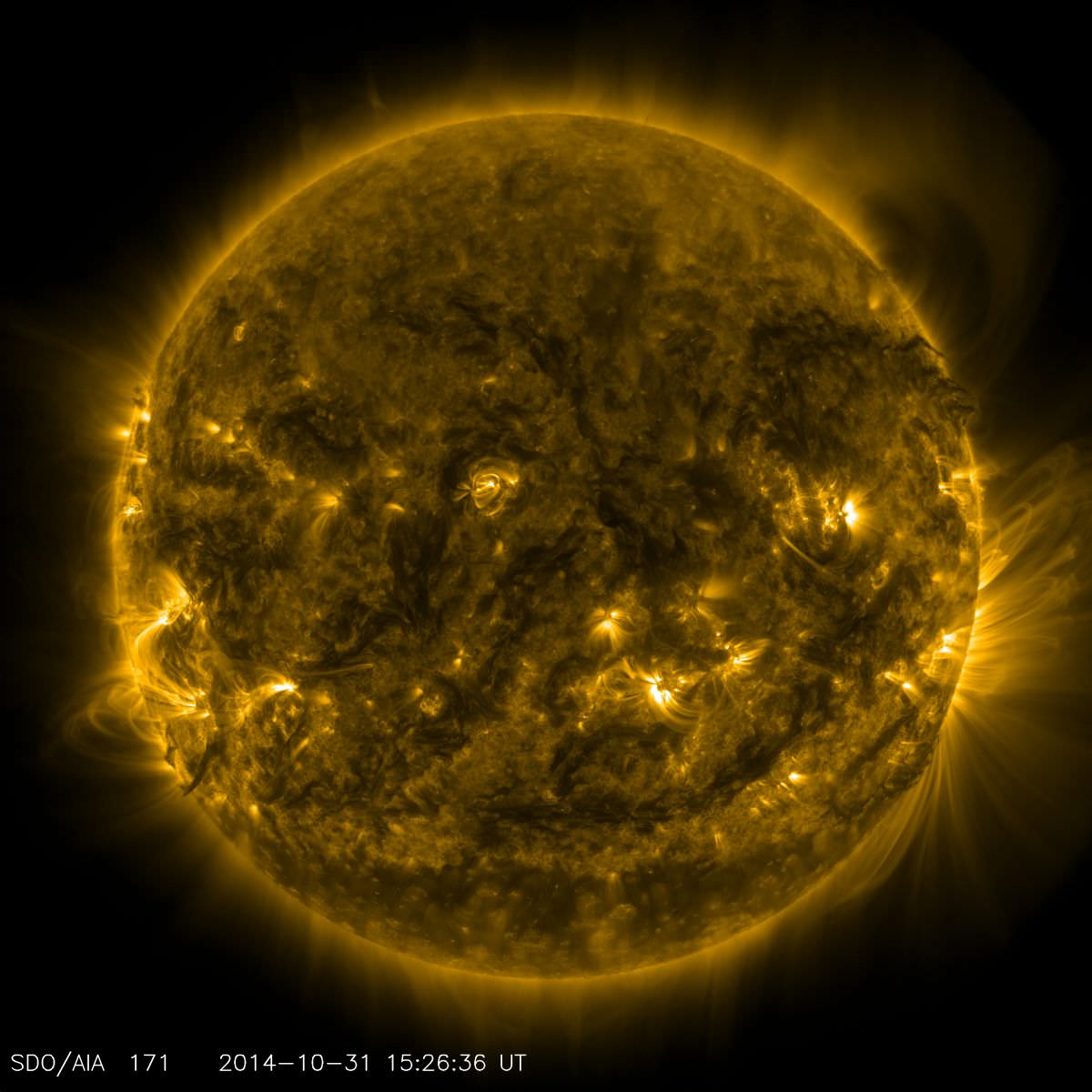

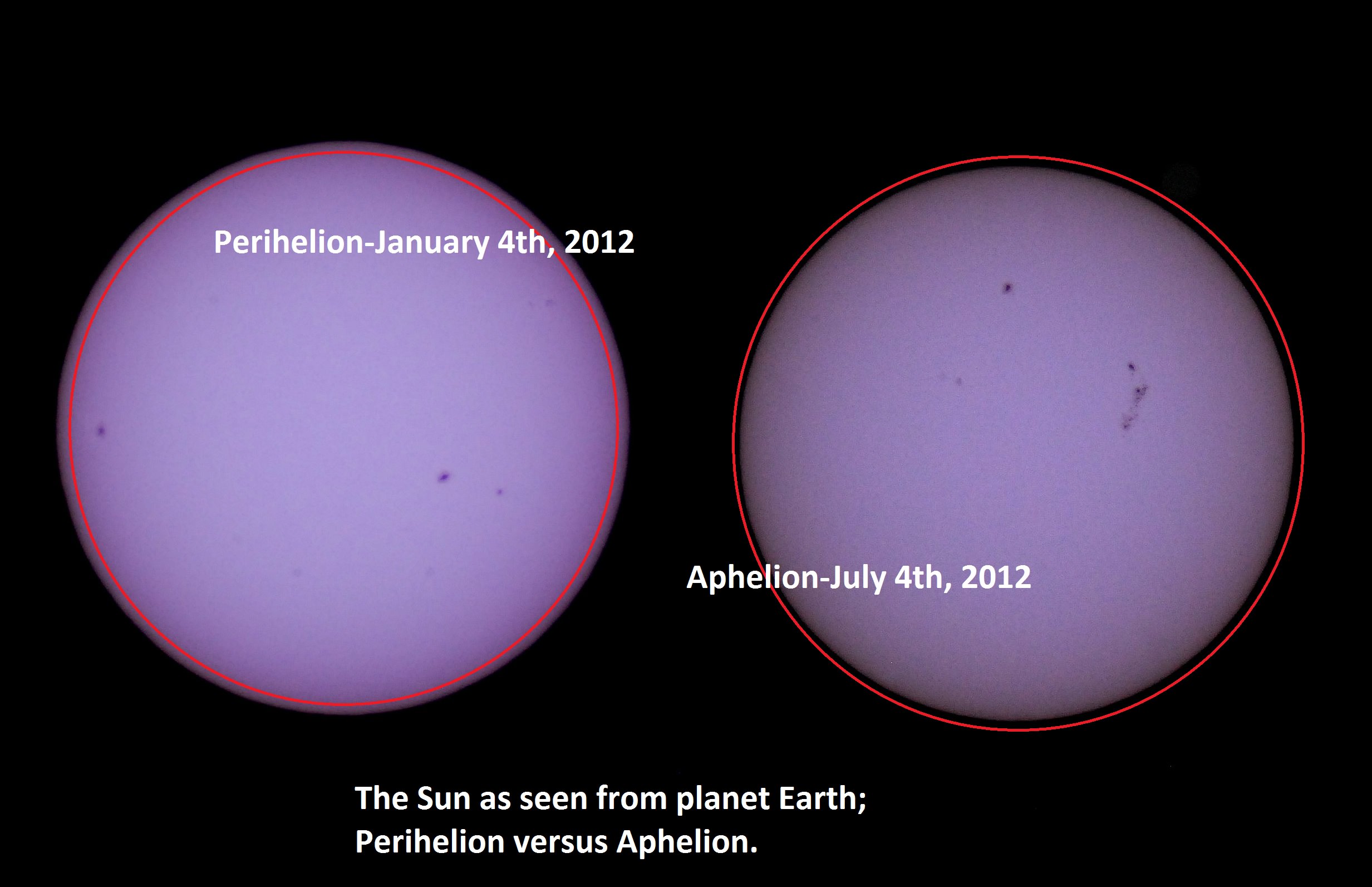

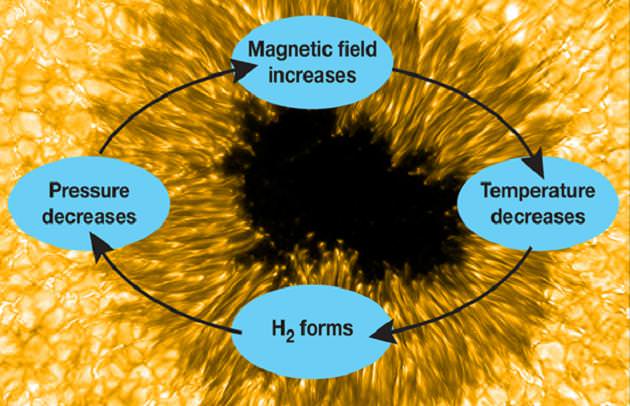

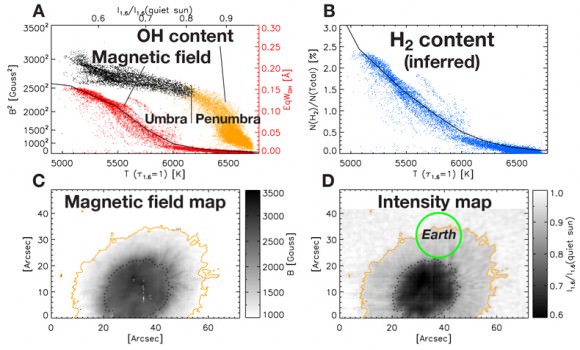

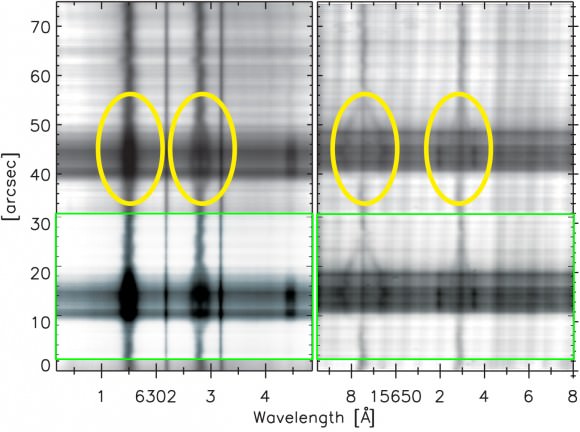

One such mystery confronting solar dynamics is exactly what drives the periodicity related to the solar cycle. Follow our star with a backyard telescope over a period of years, and you’ll see sunspots ebb and flow in an 11 year period of activity. The dazzling ‘surface’ of the Sun where these spots are embedded is actually the photosphere, and using a small telescope tuned to hydrogen-alpha wavelengths you can pick up prominences in the warmer chromosphere above.

This cycle is actually is 22 years in length (that’s 11 years times two), as the Sun flips polarity each time. A hallmark of the start of each solar cycle is the appearance of sunspots at high solar latitudes, which then move closer to the solar equator as the cycle progresses. You can actually chart this distribution in a butterfly diagram known as a Spörer chart, and this pattern was first recognized by Gustav Spörer in the late 19th century and is known as Spörer’s Law.

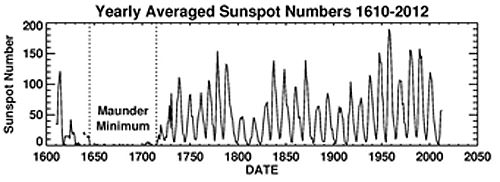

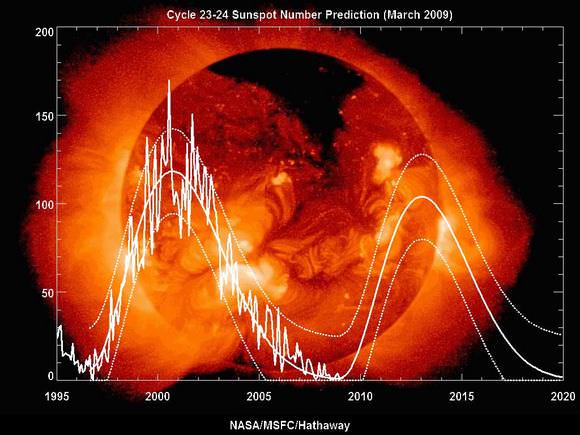

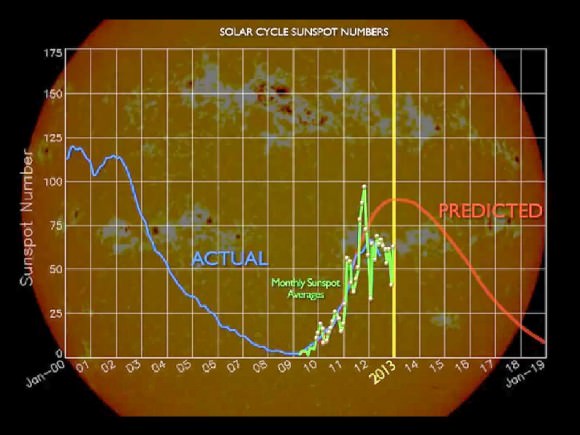

We’re currently in the midst of solar cycle #24, and the measurement of solar cycles dates all the way back to 1755. Galileo observed sunspots via projection (the tale that he went blind observing the Sun in apocryphal). We also have Chinese records going back to 364 BC, though historical records of sunspot activity are, well, spotty at best. The infamous Maunder Minimum occurred from 1645 to 1717 just as the age of telescopic astronomy was gaining steam. This dearth of sunspot activity actually led to the idea that sunspots were a mythical creation by astronomers of the time.

But sunspots are a true reality. Spots can grow larger than the Earth, such as sunspot active region 2192, which appeared just before a partial solar eclipse in 2014 and could be seen with the unaided (protected) eye. The Sun is actually a big ball of gas, and the equatorial regions rotate once every 25 days, 9 days faster than the rotational period near the poles. And speaking of which, it is not fully understood why we never see sunspots at the solar poles, which are tipped 7.25 degrees relative to the ecliptic.

Other solar mysteries persist. One amazing fact about our Sun is the true age of the sunlight shining in our living room window. Though it raced from the convective zone and through the photosphere of the Sun at 300,000 km per second and only took 8 minutes to get to your sunbeam-loving cat here on Earth, it took an estimated 10,000 to 170,000 years to escape the solar core where fusion is taking place. This is due to the terrific density at the Sun’s center, over seven times that of gold.

Another amazing fact is that we can actually model the happenings on the farside of the Sun utilizing a new fangled method known as helioseismology.

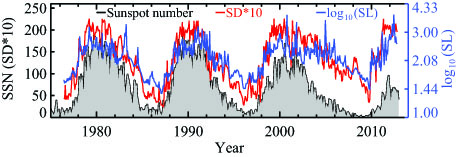

Another key mystery is why the current solar cycle is so weak… it has even been proposed that solar cycle 25 and 26 might be absent all together. Are there larger solar cycles waiting discovery? Again, we haven’t been watching the Sun close enough for long enough to truly ferret these ‘Grand Cycles’ out.

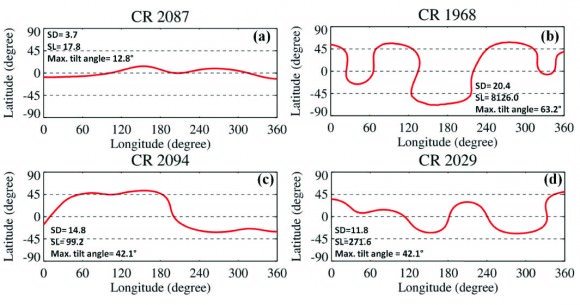

Are sunspot numbers telling us the whole picture? Sunspot numbers are calculated using formula that includes a visual count of sunspot groups and the individual sunspots in them that are currently facing Earthward, and has long served as the gold standard to gauge solar activity. Research conducted by the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in 2013 has suggested that the orientation of the heliospheric current sheet might actually provide a better picture as to the goings on of the Sun.

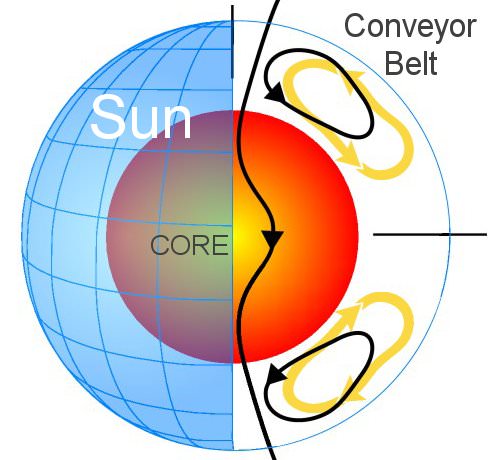

Another major mystery is why the Sun has this 22/11 year cycle of activity in the first place. The differential rotation of the solar interior and convective zone known as the solar tachocline drives the powerful solar dynamo. But why the activity cycle is the exact length that it is is still anyone’s guess. Perhaps the fossil field of the Sun was simply ‘frozen’ in the current cycle as we see it today.

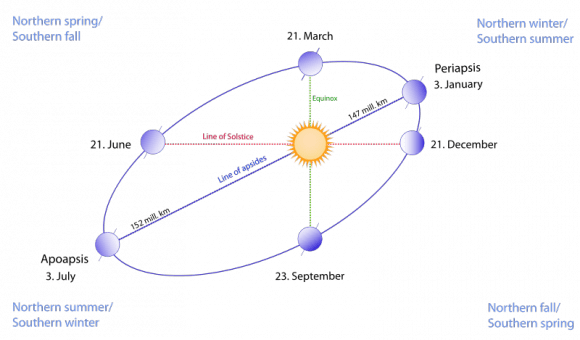

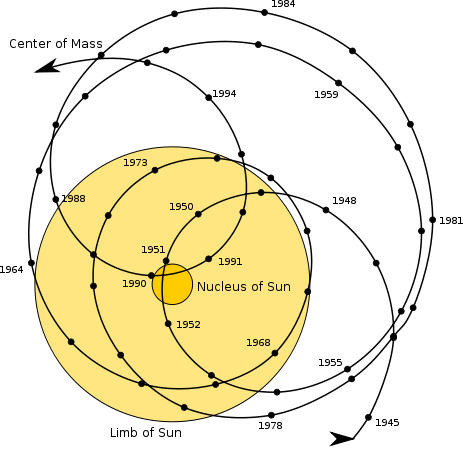

There are ideas out there that Jupiter drives the solar cycle. A 2012 paper suggested just that. It’s an enticing theory for sure, as Jupiter orbits the Sun once every 11.9 years.

And a recent paper has even proposed that Uranus and Neptune might drive much longer cycles…

Color us skeptical on these ideas. Although Jupiter accounts for over 70% of the planetary mass in the solar system, it’s 1/1000th as massive as the Sun. The barycenter of Jupiter versus the Sun sits 36,000 kilometres above the solar surface, tugging the Sun at a rate of 12.4 metres per second.

I suspect this is a case of coincidence: the solar system provides lots of orbital periods of varying lengths, offering up lots of chances for possible mutual occurrences. A similar mathematical curiosity can be seen in Bode’s Law describing the mathematical spacing of the planets, which to date, has no known basis in reality. It appears to be just a neat play on numbers. Roll the cosmic dice long enough, and coincidences will occur. A good test for both ideas would be the discovery of similar relationships in other planetary systems. We can currently detect both starspots and large exoplanets: is there a similar link between stellar activity and exoplanet orbits? Demonstrate it dozens of times over, and a theory could become law.

That’s science, baby.