If you’ve read enough of our articles, you know I’ve got an uneasy alliance with the Sun. Sure, it provides the energy we need for all life on Earth. But, it’s a great big ongoing thermonuclear reaction, and it’s right there! As soon as we get fusion, Sun, in like, 30 years or so, I tell you, we’ll be the ones laughing.

But to be honest, we still have so many questions about the Sun. For starters, we don’t fully understand the solar wind blasting out of the Sun. This constant wind of charged particles is constantly blowing out into space, but sometimes it’s stronger, and sometimes it’s weaker.

What are the factors that contribute to the solar wind? And as you know, these charged particles are not healthy for the human body, or for our precious electronics. In fact, the Sun occasionally releases enormous blasts that can damage our satellites and electrical grids.

How can we predict the intensity so that we can be better prepared for dangerous solar storms? Especially the Carrington-class events that might take down huge portions of our modern society.

Perhaps the biggest mystery with the Sun is the temperature of its corona. The surface of the Sun is hot, like 5,500 degrees Celsius. But if you rise up into the atmosphere of the Sun, into its corona, the temperature jumps beyond a million degrees.

The list of mysteries is long. And to start understanding what’s going on, we’ll need to get much much closer to the Sun.

Good news, NASA has a new mission in the works to do just that.

The mission is called the Parker Solar Probe. Actually, last week, it was called the Solar Probe Plus, but then NASA renamed it, and that reminded me to do a video on it.

It’s pretty normal for NASA to rename their spacecraft, usually after a dead astronomer/space scientist, like Kepler, Chandra, etc. This time, though, they renamed it for a legendary solar astronomer Eugene Parker, who developed much of our modern thinking on the Sun’s solar wind. Parker just turned 90 and this is the first time NASA has named it after someone living.

Anyway, back to the spacecraft.

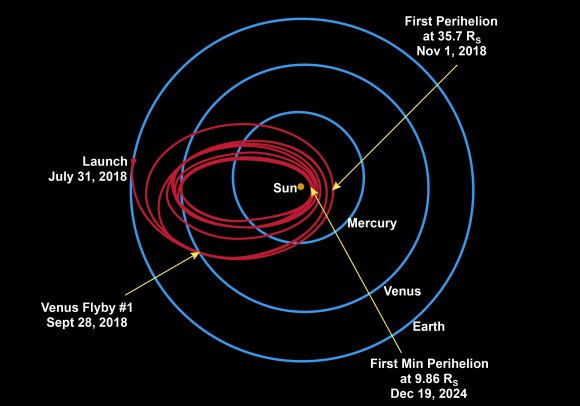

The mission is due to launch in early August 2018 on a Delta IV Heavy, so we’re still more than a year away at this point. When it does, it’ll carry the spacecraft on a very unusual trajectory through the inner Solar System.

The problem is that the Sun is actually a very difficult place to reach. In fact, it’s the hardest place to get to in the entire Solar System.

Remember that the Earth is traveling around the Sun at a velocity of 30 km/s. That’s almost three times the velocity it takes to get into orbit. That’s a lot of velocity.

In order to be able to get anywhere near the Sun, the probe needs to shed velocity. And in order to do this, it’s going to use gravitational slingshots with Venus. We’ve talked about gravitational slingshots in the past, and how you can use them to speed up a spacecraft, but you can actually do the reverse.

The Parker Solar Probe will fall down into Venus’ gravity well, and give orbital velocity to Venus. This will put it on a new trajectory which takes it closer to the Sun. It’ll do a total of 7 flybys in 7 years, each of which will tweak its trajectory and shed some of that orbital momentum.

You know, trying to explain orbital maneuvering is tough. I highly recommend that you try out Kerbal Space Program. I’ve learned more about orbital mechanics by playing that game for a few months than I have in almost 2 decades of space journalism. Go ahead, try to get to the Sun, I challenge you.

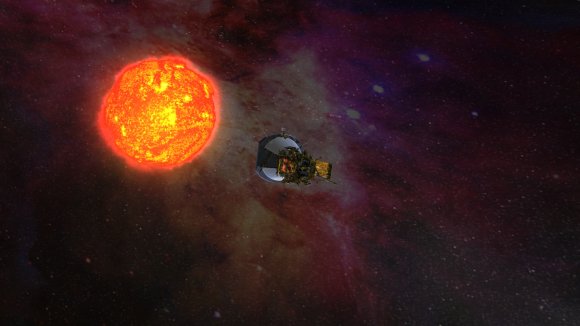

Anyway, with each Venus flyby, the Parker Solar Probe will get closer and closer to the Sun, well within the orbit of Mercury. Far closer than any spacecraft has ever gotten to the Sun. At its closest point, it’ll only be 5.9 million kilometers from the Sun. Just for comparison, the Earth orbits at an average distance of about 150 million kilometers. That’s close.

And over the course of its entire mission, the spacecraft is expected to make a total of 24 complete orbits of the Sun, analyzing that plasma ball from every angle.

The orbit is also highly elliptical, which means that it’s going really really fast at its closest point. Almost 725,000 km/h.

In order to withstand the intense temperatures of being this close to the Sun, NASA has engineered the Parker Solar Probe to shed heat. It’s equipped with an 11.5 cm-thick shield made of carbon-composite. For that short time it spends really close to the Sun, the spacecraft will keep the shield up, blocking that heat from reaching the rest of its instruments.

And it’s going to get hot. We’re talking about more than 1,300 degrees Celsius, which is about 475 times as much energy as a spacecraft receives here on Earth. In the outer Solar System, the problem is that there just isn’t enough energy to power solar panels. But where Parker is going, there’s just too much energy.

Now we’ve talked about the engineering difficulties of getting a spacecraft this close to the Sun, let’s talk about the science.

The biggest question astronomers are looking to solve is, how does the corona get so hot. The surface is 5,500 Celsius. As you get farther away from the Sun, you’d expect the temperature to go down. And it certainly does once you get as far as the orbit of the Earth.

But the Sun’s corona, or its outer atmosphere, extends millions of kilometers into space. You can see it during a solar eclipse as this faint glow around the Sun. Instead of dropping, the temperature rises to more than a million degrees.

What could be causing this? There are a couple of ideas. Plasma waves pushed off the Sun could bunch up and release their heat into the corona. You could also get the crisscrossing of magnetic field lines that create mini-flares within the corona, heating it up.

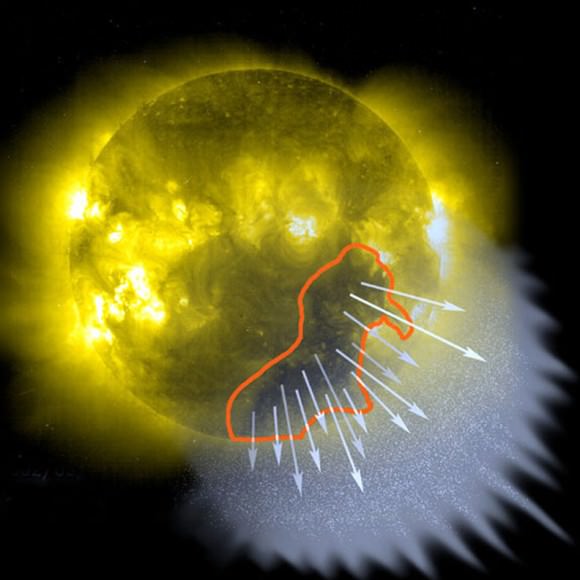

The second great mystery is the solar wind, the stream of charged protons and electrons coming from the Sun. Instead of a constant blowing wind, it can go faster or slower. And when the speed changes, the contents of the wind change too.

There’s the slow wind, that goes a mere 1.1 million km/h and seems to emanate from the Sun’s equatorial regions. And then the fast wind, which seems to be coming out of coronal holes, cooler parts in the Sun’s corona, and can be going at 2.7 million km/h.

Why does the solar wind speed change? Why does its consistency change?

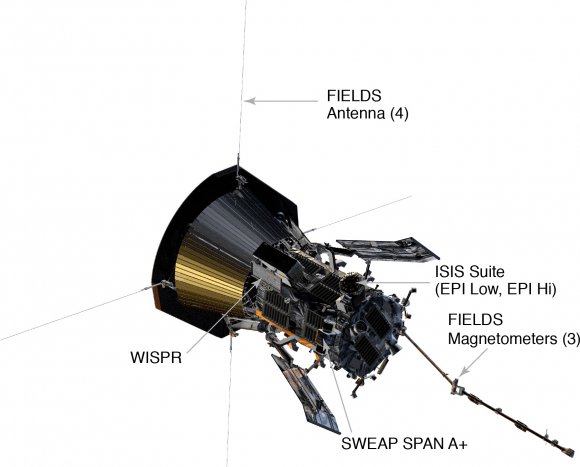

The Parker Solar Probe is equipped with four major instruments, each of which will gather data from the Sun and its environment.

The FIELDS experiment will measure the electric and magnetic fields and waves around the Sun. We know that much of the Sun’s behavior is driven by the complex interaction between charged plasma in the Sun. In fact, many physicists agree that magnetohydrodynamics is easily one of the most complicated fields you can get into.

Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun, or ISOIS (which I suspect needs a renaming) will measure the charged particles streaming off the Sun, during regular solar activity and during dangerous solar storms. Can we get any warning before these events occur, giving astronauts more time to protect themselves?

Wide-field Imager for Solar PRobe or WISPR is its telescope and camera. It’s going to be taking close up, high resolution images of the Sun and its corona that will blow our collective minds… I hope. I mean, if it’s just a bunch of interesting data and no pretty pictures, it’s going to be hard to make cool videos showcasing the results of the mission. You hear me NASA, we want pictures and videos. And science, sure.

And then the Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons Investigation, or SWEAP, will measure type, velocity, temperature and density of particles around the Sun, to help us understand the environment around it.

One interesting side note, the spacecraft will be carrying a tiny chip on board with photos of Eugene Parker and a copy of his original 1958 paper explaining the Sun’s solar wind.

I know we’re still more than a year away from liftoff, and several years away before the science data starts pouring in. But you’ll be hearing more and more about this mission shortly, and I’m pretty excited about what it’s going to accomplish. So stay tuned, and once the science comes in, I’m sure you’ll hear plenty more about it.