[/caption]

Despite being an idea rattling around inside the head of engineers and space enthusiasts for over 40 years, solar sails have never really gained much traction in the way of actual deployment. Today, NASA has taken an important step towards testing solar sail technology for use in future spacecraft.

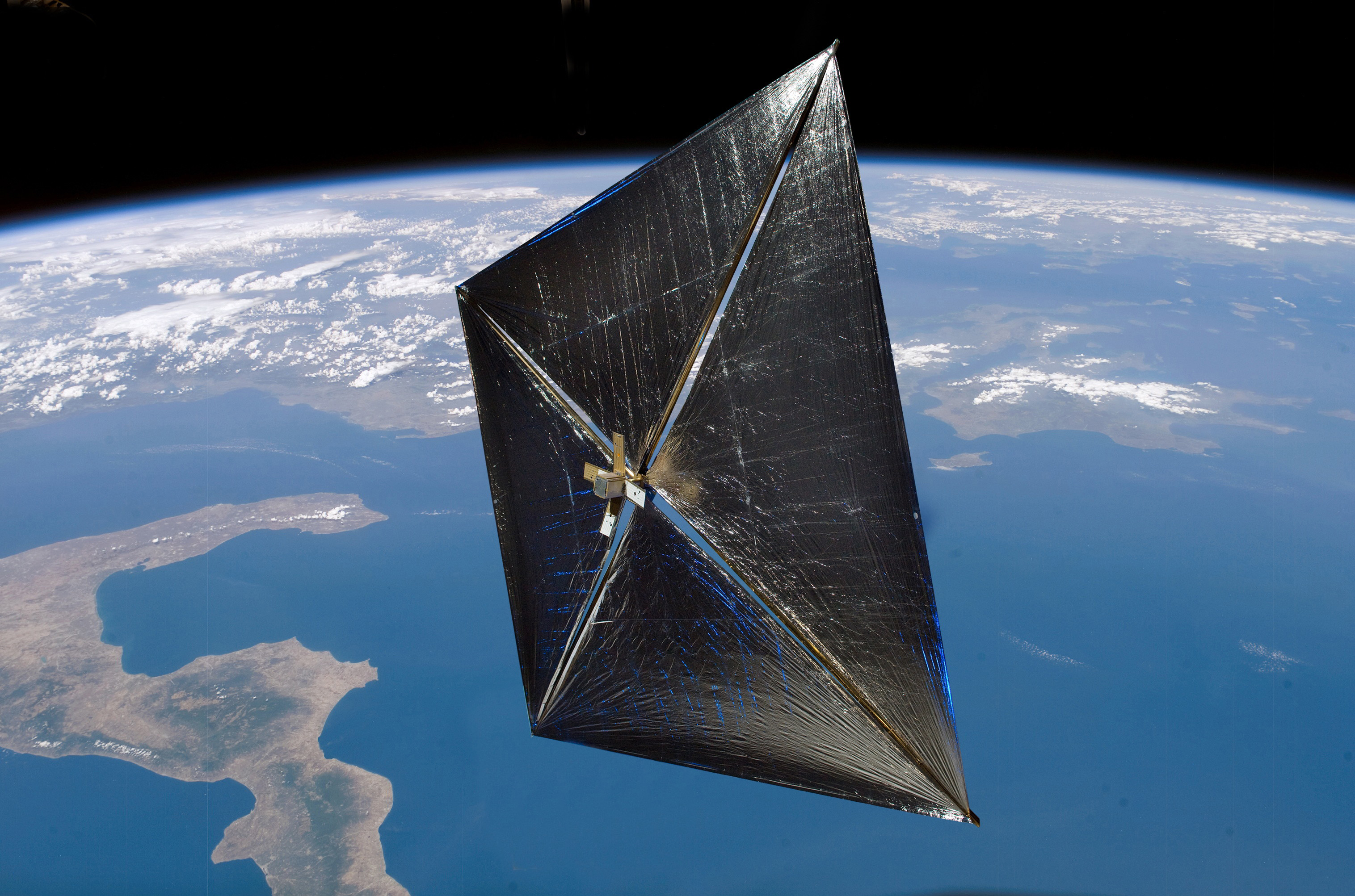

The Nanosail-D spacecraft was launched Friday, Nov. 19 at 8:25 p.m. EST from Kodiak Island, Alaska, and was piggybacking on another satellite, both aboard a Minotaur IV rocket. It has successfully been ejected from the launch vehicle as of today, and is on its own. Though the sails have yet to deploy, this is already an achievement that bodes well for the future of both solar sail and small satellite technology.

The Nanosail-D satellite – commonly described as “loaf of bread” sized – was ejected from the Fast, Affordable, Science and Technology Satellite (FASTSAT) at 1:31 a.m. EST December 6th. Not only is this NASA’s first attempt at deploying a solar sail in space, but this also marks the first time a nanosatellite has been ejected from another satellite, proving that this is a reliable way to get multiple satellites into orbit at the same time.

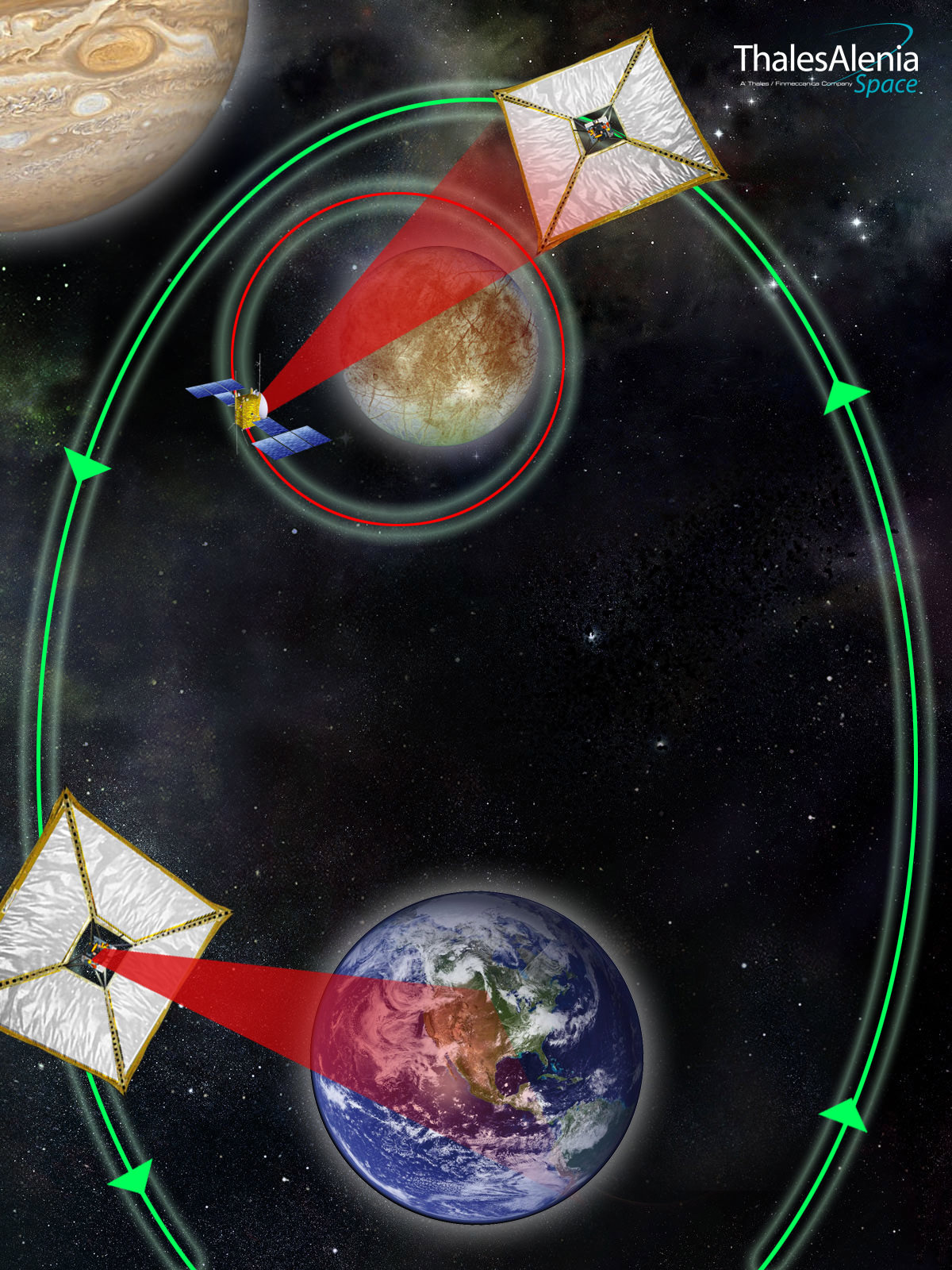

Nanosail-D is a nanosatellite – or cubesat – designed to test the potential for solar sails in atmospheric braking. Such sails – made from a an ultra-thin and light material, in this case the polymer CP1 – could potentially be used to propel a spacecraft outside of our Solar System. The Nanosail-D sail will be deployed in low-Earth orbit, about 650 km (400 miles) up. The sail will be used to show how such technology could slow down satellites when they need to de-orbit.

Currently, de-orbiting satellites involves maneuvering them into a lower and lower orbit using the engines of the satellite, which necessitates more propellant aboard the spacecraft simply to dispose of it properly. Nanosail-D will deploy a solar sail and orbit for 70-120 days, eventually spiraling into the Earth’s atmosphere to burn up.

Since it will be orbiting so close to the Earth, its potential for testing solar sails as propulsion is not the focus of the mission; however, the deployment of a solar sail is itself a huge engineering challenge. Nanosail-D will be the perfect experiment to test out whether the method NASA will be using to unfurl the sail is workable in space.

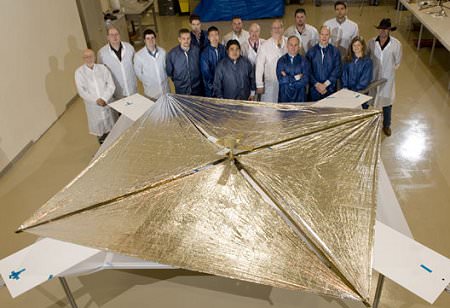

Immediately after the ejection earlier today, a timer started a three-day countdown. Once it reaches zero, it will go boom – that is, four booms will spring out from the small satellite, and within five seconds the sail will be fully extended to its 100 square foot (10 square meter) sail-span.

Dean Alhorn, NanoSail-D principal investigator and aerospace engineer at the Marshall Space Flight Center explains on the mission page, “The deployment works in the exact opposite way of carpenter’s measuring tape. With a measuring tape, you pull it out, which winds up a spring, and when you let it go it is quickly pulled back in. With NanoSail-D, we wind up the booms around the center spindle. Those wound-up booms act like the spring. Approximately seven days after launch, it deploys the sail off the center spindle.”

There have been other attempts at launching and deploying solar sails before, but once deployed, Nanosail D will be the longest-running solar sail experiment yet attempted. Both JAXA and the Russian space agency have deployed successful solar sail experiments.

JAXA launched a clover-shaped sail aboard a sounding rocket in 2004, and the experiment lasted about 400 seconds. They also launched the IKAROS spacecraft in May, 2010, which is currently en-route to Venus, and will fly to the opposite side of Sun from Earth. The Russians deployed a 20-meter diameter mirror successfully aboard the Progress M-15 resupply mission to Mir in 1993. Named Znamya 2, the mirror cast a 5km (3 mile)-wide bright spot on the ground that swept across southern France to western Russia, and orbited for several hours before burning up.

The Planetary Society is probably the most vocal and enthusiastic organization in support of solar sail technology. They are currently developing a solar sail similar to that of Nanosail-D, called Lightsail-1. The society attempted a launch of a solar sail called Cosmos 1 in 2005, but the rocket carrying the satellite did not fire during its second stage, and the craft was lost.

Nanosail-D is in its second iteration. The first spacecraft was commissioned in early 2008, and the team – astrophysicists and engineers at the Marshall Space Flight Center and the Ames Research Center – had four months to put together a workable satellite. It launched aboard a Falcon 1 rocket in August of 2008, but the rocket burned up in the atmosphere. If engineers are good at one thing, it’s redundancy – the team had constructed a second Nanosail-D, and had ample time to work out some of the bugs and develop the technology even more.

The Planetary Society almost had a chance to launch Nanosail-D, according to Louis Friedman, executive director of the The Planetary Society, they were contacted by the team developing Nanosail-D after the failed initial launch attempt, and asked if they would like to help launch the second Nanosail-D spacecraft. The Planetary Society agreed, but the team then found space aboard the FASTSAT launch. Consequently, Lightsail-D was borne out of this brief collaboration.

The timer is silently counting down what promises to be an exciting mission, and potential milestone in the future of spaceflight. Watch this space for further developments on the mission.

Sources: NASA press release, The Planetary Society, NASA Science, NASA Nanosail-D fact-sheet