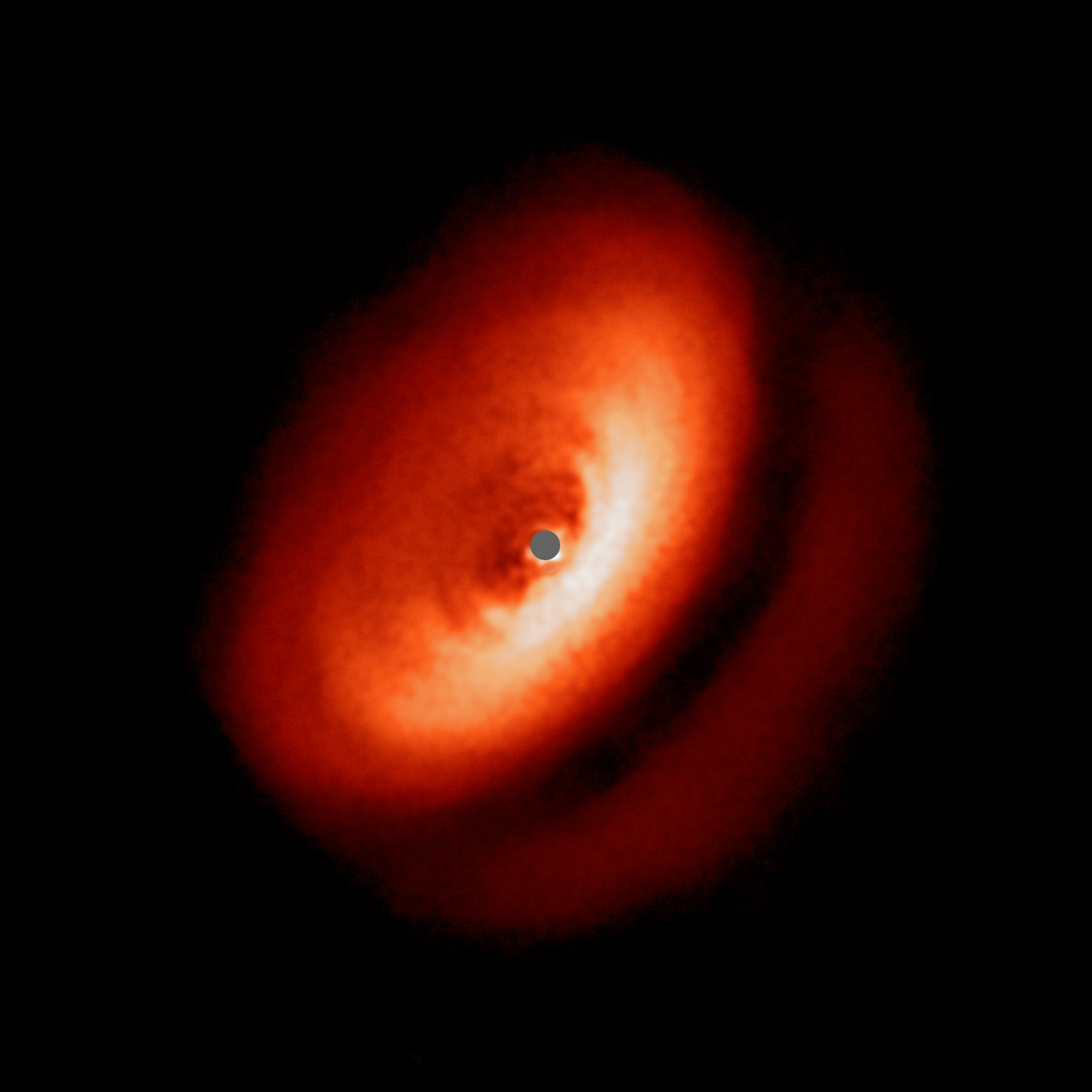

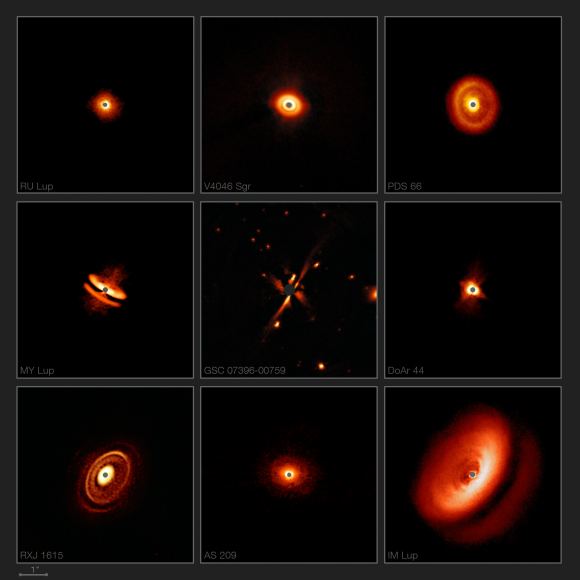

For centuries, astronomers and scientists have sought to understand how our Solar System came to be. Since that time, two theories have become commonly-accepted that explain how it formed and evolved over time. These are the Nebular Hypothesis and the Nice Model, respectively. Whereas the former contends that the Sun and planets formed from a large cloud of dust and gas, the latter maintains the giant planets have migrated since their formation.

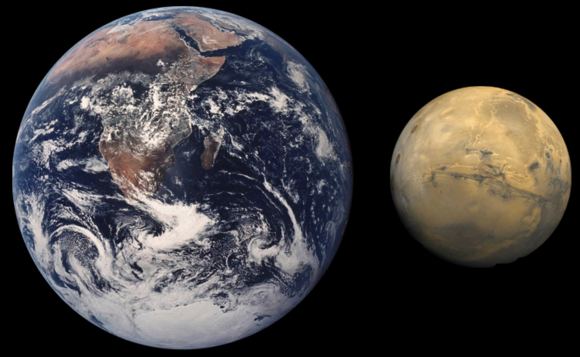

This is what has led to the Solar System as we know it today. However, an enduring mystery about these theories is how Mars came to be the way it is. Why, for example, is it significantly smaller than Earth and inhospitable to life as we know it when all indications show that it should be comparable in size? According to a new study by an international team of scientists, the migration of the giant planets could have been what made the difference.

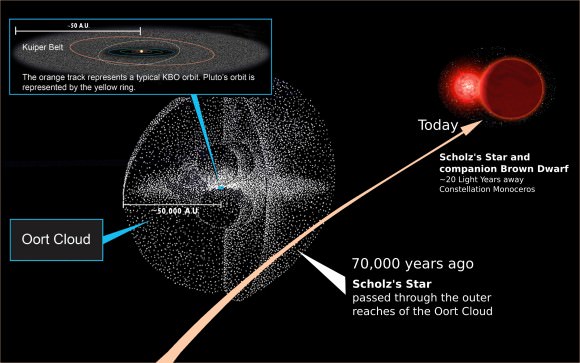

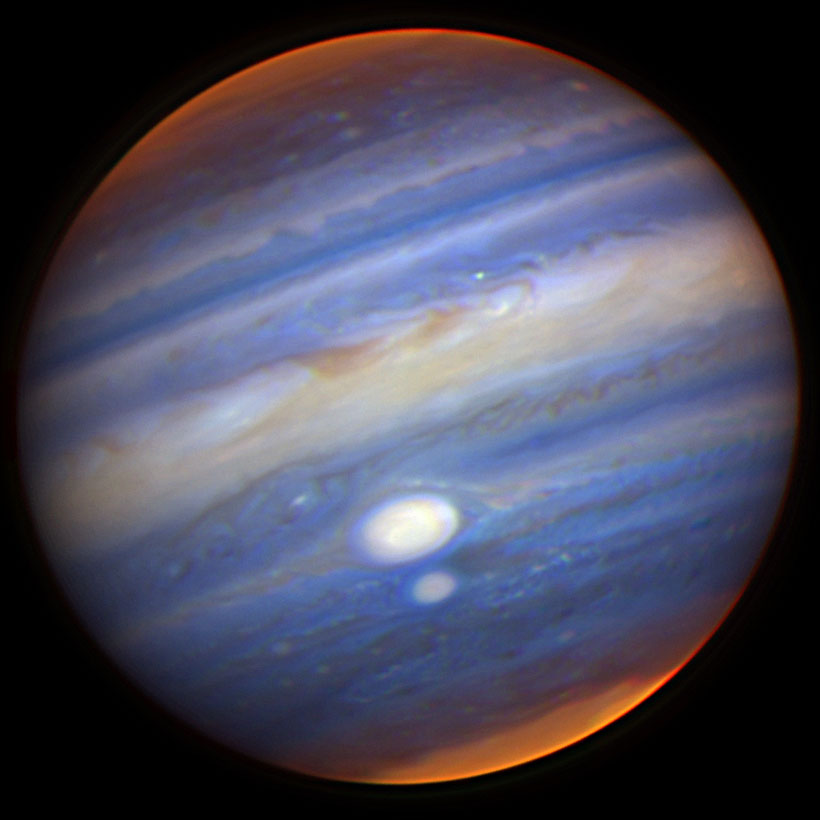

For over a decade, astronomers have been operating under the assumption that shortly after the formation of the Solar System, the gas and ice giants of the outer Solar System (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) began to migrate outward. This is the substance of the Nice Model, which asserts that this migration had a profound effect on the evolution of the Solar System and the formation of the terrestrial planets.

This model – named for the location of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur (in Nice, France), where it was initially developed – began as an evolutionary model that helped explain the observed distributions of small objects like comets and asteroids. As Matt Clement, a graduate student in the HL Dodge Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Oklahoma and the lead author on the paper, explained to Universe Today via email:

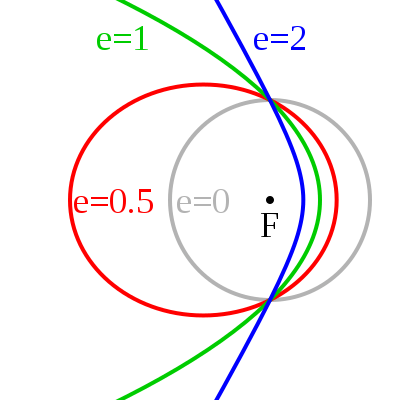

“In the model, the giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) originally formed much closer to the Sun. In order to reach their current orbital locations, the entire solar system undergoes a period of orbital instability. During this unstable period, the size and the shape of the giant planet’s orbits change rapidly.”

For the sake of their study, which was recently published in the scientific journal Icarus under the title “Mars Growth Stunted by an Early Giant Planet Instability“, the team expanded on the Nice Model. Through a series of dynamical simulations, they attempted to show how, during the early Solar System, the growth of Mars was halted thanks to the orbital instabilities of the giant planets.

The purpose of their study was also to address a flaw in the Nice Model, which is how the terrestrial planets could have survived a serious shake up of the Solar System. In the original version of the Nice Model, the instability of the giant planets occurred a few hundred million years after the planets formed, which coincided with the Late Heavy Bombardment – when the inner Solar System was bombarded by a disproportionately large number of asteroids.

This period is evidenced by spike in the Moon’s cratering record, which was inferred from an abundance of samples from the Apollo missions with similar geological dates. As Clement explained:

“A problem with this is that it is difficult for the terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars) to survive the violent instability without being ejected out of the solar system or colliding with one another. Now that we have better, high resolution images of lunar craters and more accurate methods for dating the Apollo samples, the evidence for a spike in lunar cratering rates is diminishing. Our study investigated whether moving the instability earlier, while the inner terrestrial planets were still forming, could help them survive the instability, and also explain why Mars is so small relative to the Earth.”

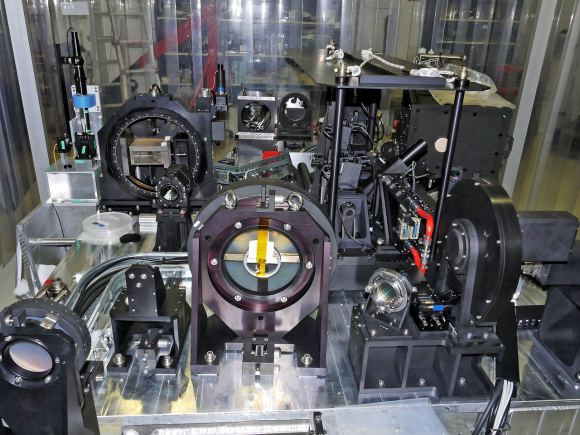

Clement was joined by Nathan A. Kaib, a OU astrophysics professor, as well as Sean N. Raymond of the University of Bordeaux and Kevin J. Walsh from the Southwest Research Institute. Together, they used the computing resources of the OU Supercomputing Center for Education and Research (OSCER) and the Blue Waters supercomputing project to perform 800 dynamical simulations of the Nice model to determine how it would impact Mars.

These simulations incorporated recent geological evidence from Mars and Earth that indicate that Mars’ formation period was about 1/10th that of Earth’s. This has led to the theory that Mars was left behind as a “stranded planetary embryo” during the formation of the Sun’s inner planets. As Prof. Kaib explained to Universe Today via email, this study was therefore intended to test how Mars emerged from planetary formation as a planetary embryo:

“We simulated the “giant impact phase” of terrestrial planet formation (the final stage of the formation process). At the beginning of this phase, the inner Solar System (0.5-4 AU) consists of a disk of about 100 moon-to-mars-sized planetary embryos embedded in a sea of much smaller, more numerous rocky planetesimals. Over the course of 100-200 million years the bodies making up this system collide and merge into a handful (typically 2-5) rocky planetary mass bodies. Normally, these types of simple initial conditions build planets on Mars-like orbits that are about 10x more massive than Mars. However, when the terrestrial planet formation process is interrupted by the Nice model instability, many of the planet building blocks near the Mars region are lost or tossed into the Sun. This limits the growth of Mars-like planets and produces a closer match to our actual inner solar system.”

What they found was that this revised timeline explained the disparity between Mars and Earth. In short, Mars and Earth vary considerably in size, mass and density because the giant planets became unstable very early in the Solar System’s history. In the end, this is what allowed Earth to become the only life-bearing terrestrial planet in the Solar System, and for Mars to become the cold, desiccated and thinly-atmosphered place that it is today.

As Prof. Kaib explained, this is not the only model for explaining the disparity between Earth and Mars, but the evidence all fits:

“Without this instability, Mars likely would have had a mass closer to Earth’s and would be a very different, perhaps more Earth-like, planet compared to what it is today,” he said. “I should also say that this is not the only mechanism capable of explaining the low mass of Mars. However, we already know that the Nice model does an excellent job of reproducing many features of the outer Solar System, and if it occurs at the right time in the Solar System’s history it also ends up explaining our inner Solar System.”

This study could also have drastic implications when it comes to the study of extra-solar systems. At present, our models for how planets form and evolve are based on what we have been able to learn from our own Solar System. Hence, by learning more about how gas giants and terrestrial planets grew and assumed their current orbits, scientists will be able to create more comprehensive models of how life-bearing planets could merge around other stars.

It certainly would help narrow the search for “Earth-like” planets and (dare we dream?) planets that support life.

Further Reading: University of Oklahoma, Icarus