When it comes to looking beyond our Solar System, astronomers are often forced to theorize about what they don’t know based on what they do. In short, they have to rely on what we have learned studying the Sun and the planets from our own Solar System in order to make educated guesses about how other star systems and their respective bodies formed and evolved.

For example, astronomers have learned much from our Sun about how convection plays a major role in the life of stars. Until now, they have not been able to conduct detailed studies of the surfaces of other stars because of their distances and obscuring factors. However, in a historic first, an international team of scientists recently created the first detailed images of the surface of a red giant star located roughly 530 light-years away.

The study recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature under the title “Large Granulation cells on the surface of the giant star Π¹ Gruis“. The study was led by Claudia Paladini of the Université libre de Bruxelles and included members from the European Southern Observatory, the Université de Nice Sophia-Antipolis, Georgia State University, the Université Grenoble Alpes, Uppsala University, the University of Vienna, and the University of Exeter.

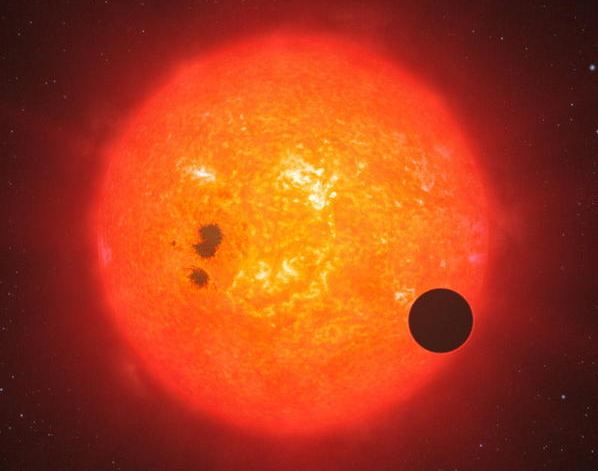

For the sake of their study, the team used the Precision Integrated-Optics Near-infrared Imaging ExpeRiment (PIONIER) instrument on the ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) to observe the star known as Π¹ Gruis. Located 530 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Grus (The Crane), Π1 Gruis is a cool red giant. While it is the same mass as our Sun, it is 350 times larger and several thousand times as bright.

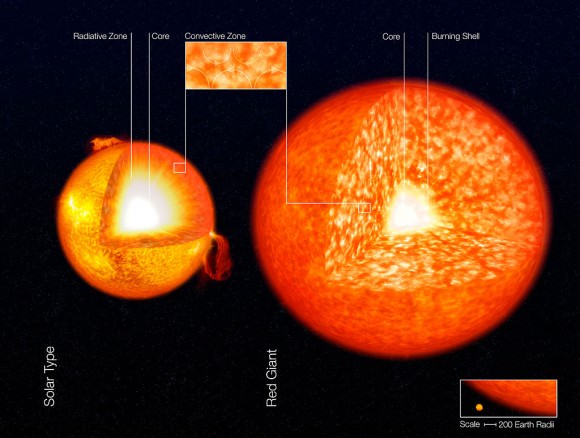

For decades, astronomers have sought to learn more about the convection properties and evolution of stars by studying red giants. These are what become of main sequence stars once they have exhausted their hydrogen fuel and expand to becomes hundreds of times their normal diameter. Unfortunately, studying the convection properties of most supergiant stars has been challenging because their surfaces are frequently obscured by dust.

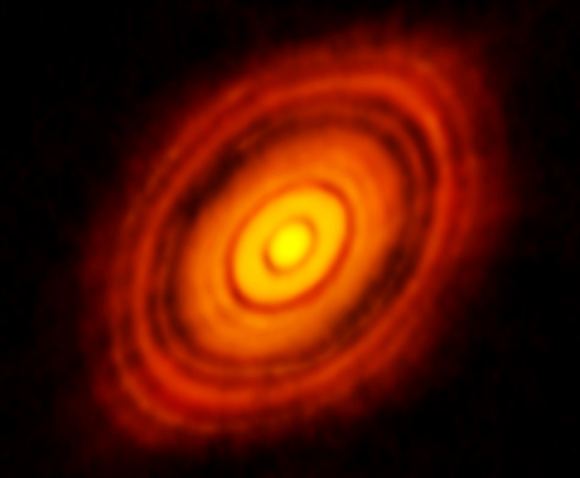

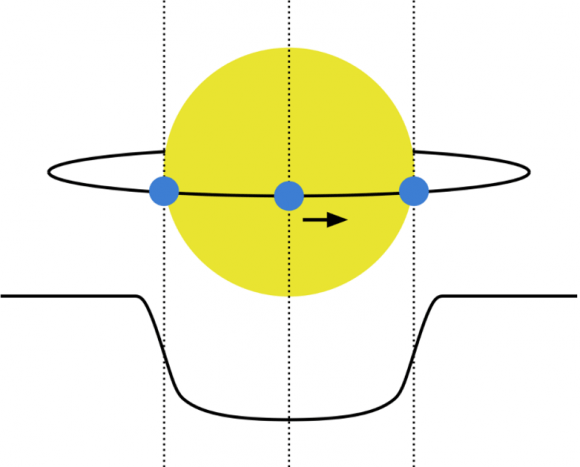

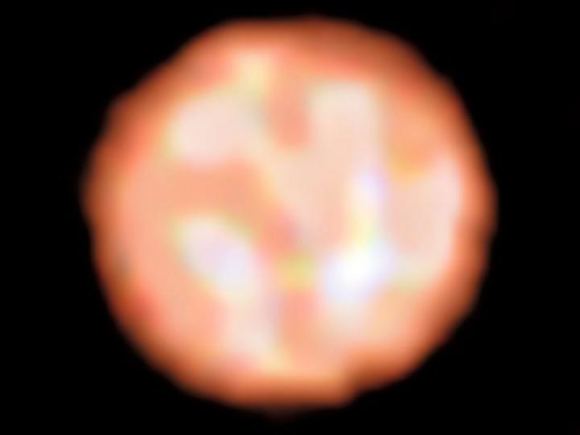

After obtaining interferometric data on Π1 Gruis in September of 2014, the team then relied on image reconstruction software and algorithms to compose images of the star’s surface. These allowed the team to determine the convection patterns of the star by picking out its “granules”, the large grainy spots on the surface that indicate the top of a convective cell.

This was the first time that such images have been created, and represent a major breakthrough when it comes to our understanding of how stars age and evolve. As Dr. Fabien Baron, an assistant professor at Georgia State University and a co-author on the study, explained:

“This is the first time that we have such a giant star that is unambiguously imaged with that level of details. The reason is there’s a limit to the details we can see based on the size of the telescope used for the observations. For this paper, we used an interferometer. The light from several telescopes is combined to overcome the limit of each telescope, thus achieving a resolution equivalent to that of a much larger telescope.”

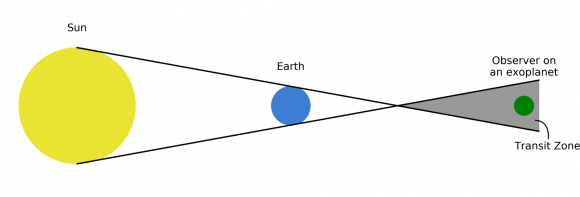

This study is especially significant because Π1 Gruis in the last major phase of life and resembles what our Sun will look like when it is at the end of its lifespan. In other words, when our Sun exhausts its hydrogen fuel in roughly five billion years, it will expand significantly to become a red giant star. At this point, it will be large enough to encompass Mercury, Venus, and maybe even Earth.

As a result, studying this star will give scientists insight into the future activity, characteristics and appearance of our Sun. For instance, our Sun has about two million convective cells that typically measure 2,000 km (1243 mi) in diameter. Based on their study, the team estimates that the surface of Π1 Gruis has a complex convective pattern, with granules measuring about 1.2 x 10^8 km (62,137,119 mi) horizontally or 27 percent of the diameter of the star.

This is consistent with what astronomers have predicted, which was that giant and supergiant stars should only have a few large convective cells because of their low surface gravity. As Baron indicated:

“These images are important because the size and number of granules on the surface actually fit very well with models that predict what we should be seeing. That tells us that our models of stars are not far from reality. We’re probably on the right track to understand these kinds of stars.”

The detailed map also indicated differences in surface temperature, which were apparent from the different colors on the star’s surface. This are also consistent with what we know about stars, where temperature variations are indicative of processes that are taking place inside. As temperatures rise and fall, the hotter, more fluid areas become brighter (appearing white) while the cooler, denser areas become darker (red).

Looking ahead, Paladini and her team want to create even more detailed images of the surface of giant stars. The main aim of this is to be able to follow the evolution of these granules continuously, rather than merely getting snapshots of different points in time.

From these and similar studies, we are not only likely to learn more about the formation and evolution of different types of stars in our Universe; we’re also sure to get a better understanding of what our Solar System is in for.

Further Reading: Georgia State University, ESO, Nature

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. The Viking Landers were the last missions to directly look for life on Mars. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1-580x458.jpg)