Science fiction has told us again and again, we belong out there, among the stars. But before we can build that vast galactic empire, we’ve got to learn how to just survive in space. Fortunately, we happen to live in a Solar System with many worlds, large and small that we can use to become a spacefaring civilization.

This is half of an epic two-part article that I’m doing with Isaac Arthur, who runs an amazing YouTube channel all about futurism, often about the exploration and colonization of space. Make sure you subscribe to his channel.

This article is about colonizing the inner Solar System, from tiny Mercury, the smallest planet, out to Mars, the focus of so much attention by Elon Musk and SpaceX. In the other article, Isaac will talk about what it’ll take to colonize the outer Solar System, and harness its icy riches. You can read these articles in either order, just read them both.

At the time I’m writing this, humanity’s colonization efforts of the Solar System are purely on Earth. We’ve exploited every part of the planet, from the South Pole to the North, from huge continents to the smallest islands. There are few places we haven’t fully colonized yet, and we’ll get to that.

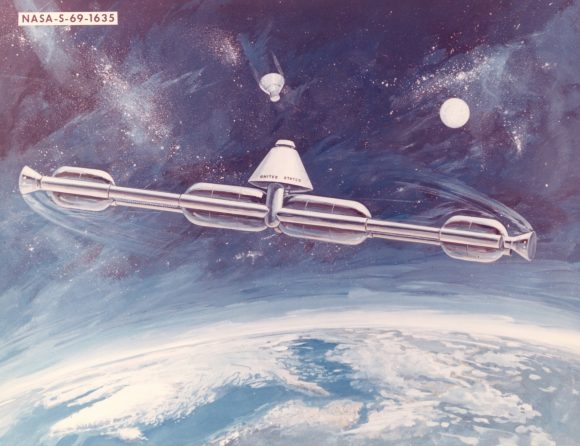

But when it comes to space, we’ve only taken the shortest, most tentative steps. There have been a few temporarily inhabited space stations, like Mir, Skylab and the Chinese Tiangong Stations.

Our first and only true colonization of space is the International Space Station, built in collaboration with NASA, ESA, the Russian Space Agency and other countries. It has been permanently inhabited since November 2nd, 2000. Needless to say, we’ve got our work cut out for us.

Before we talk about the places and ways humans could colonize the rest of the Solar System, it’s important to talk about what it takes to get from place to place.

Just to get from the surface of Earth into orbit around our planet, you need to be going about 10 km/s sideways. This is orbit, and the only way we can do it today is with rockets. Once you’ve gotten into Low Earth Orbit, or LEO, you can use more propellant to get to other worlds.

If you want to travel to Mars, you’ll need an additional 3.6 km/s in velocity to escape Earth gravity and travel to the Red Planet. If you want to go to Mercury, you’ll need another 5.5 km/s.

And if you wanted to escape the Solar System entirely, you’d need another 8.8 km/s. We’re always going to want a bigger rocket.

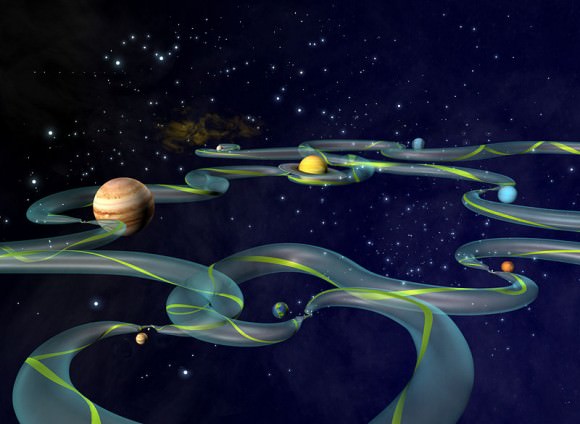

The most efficient way to transfer from world to world is via the Hohmann Transfer. This is where you raise your orbit and drift out until you cross paths with your destination. Then you need to slow down, somehow, to go into orbit.

One of our primary goals of exploring and colonizing the Solar System will be to gather together the resources that will make future colonization and travel easier. We need water for drinking, and to split it apart for oxygen to breathe. We can also turn this water into rocket fuel. Unfortunately, in the inner Solar System, water is a tough resource to get and will be highly valued.

We need solid ground. To build our bases, to mine our resources, to grow our food, and to protect us from the dangers of space radiation. The more gravity we can get the better, since low gravity softens our bones, weakens our muscles, and harms us in ways we don’t fully understand.

Each world and place we colonize will have advantages and disadvantages. Let’s be honest, Earth is the best place in the Solar System, it’s got everything we could ever want and need. Everywhere else is going to be brutally difficult to colonize and make self-sustaining.

We do have one huge advantage, though. Earth is still here, we can return whenever we like. The discoveries made on our home planet will continue to be useful to humanity in space through communications, and even 3D printing. Once manufacturing is sophisticated enough, a discovery made on one world could be mass produced half a solar system away with the right raw ingredients.

We will learn how to make what we need, wherever we are, and how to transport it from place to place, just like we’ve always done.

Mercury is the closest planet from the Sun, and one of the most difficult places that we might attempt the colonize. Because it’s so close to the Sun, it receives an enormous amount of energy. During the day, temperatures can reach 427 C, but without an atmosphere to trap the heat, night time temperatures dip down to -173 C. There’s essentially no atmosphere, 38% the gravity of Earth, and a single solar day on Mercury lasts 176 Earth days.

Mercury does have some advantages, though. It has an average density almost as high as Earth, but because of its smaller size, it actually means it has a higher percentage of metal than Earth. Mercury will be incredibly rich in metals and minerals that future colonists will need across the Solar System.

With the lower gravity and no atmosphere, it’ll be far easier to get that material up into orbit and into transfer trajectories to other worlds.

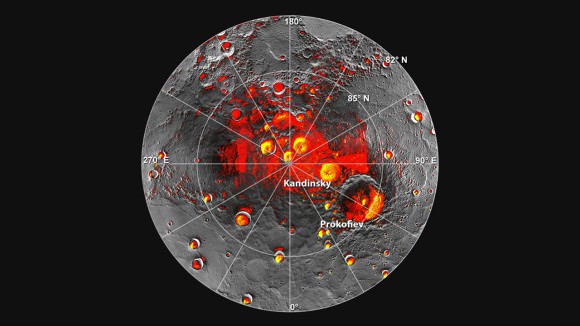

But with the punishing conditions on the planet, how can we live there? Although the surface of Mercury is either scorching or freezing, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft turned up regions of the planet which are in eternal shadow near the poles. In fact, these areas seem to have water ice, which is amazing for anywhere this close to the Sun.

You could imagine future habitats huddled into those craters, pulling in solar power from just over the crater rim, using the reservoirs of water ice for air, fuel and water.

High powered solar robots could scour the surface of Mercury, gathering rare metals and other minerals to be sent off world. Because it’s bathed in the solar winds, Mercury will have large deposits of Helium-3, useful for future fusion reactors.

Over time, more and more of the raw materials of Mercury will find their way to the resource hungry colonies spread across the Solar System.

It also appears there are lava tubes scattered across Mercury, hollows carved out by lava flows millions of years ago. With work, these could be turned into safe, underground habitats, protected from the radiation, high temperatures and hard vacuum on the surface.

With enough engineering ability, future colonists will be able to create habitats on the surface, wherever they like, using a mushroom-shaped heat shield to protect a colony built on stilts to keep it off the sun-baked surface.

Mercury is smaller than Mars, but is a good deal denser, so it has about the same gravity, 38% of Earth’s. Now that might turn out to be just fine, but if we need more, we have the option of using centrifugal force to increase it. Space Stations can generate artificial gravity by spinning, but you can combine normal gravity with spin-gravity to create a stronger field than either would have.

So our mushroom habitat’s stalk could have an interior spinning section with higher gravity for those living inside it. You get a big mirror over it, shielding you from solar radiation and heat, you have stilts holding it off the ground, like roots, that minimize heat transfer from the warmer areas of ground outside the shield, and if you need it you have got a spinning section inside the stalk. A mushroom habitat.

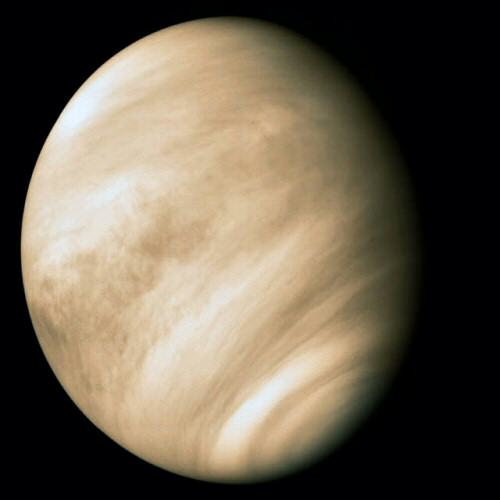

Venus is the second planet in the Solar System, and it’s the evil twin of Earth. Even though it has roughly the same size, mass and surface gravity of our planet, it’s way too close to the Sun. The thick atmosphere acts like a blanket, trapping the intense heat, pushing temperatures at the surface to 462 C.

Everywhere on the planet is 462 C, so there’s no place to go that’s cooler. The pure carbon dioxide atmosphere is 90 times thicker than Earth, which is equivalent to being a kilometer beneath the ocean on Earth.

In the beginning, colonizing the surface of Venus defies our ability. How do you survive and stay cool in a thick poisonous atmosphere, hot enough to melt lead? You get above it.

One of the most amazing qualities of Venus is that if you get into the high atmosphere, about 52.5 kilometers up, the air pressure and temperature are similar to Earth. Assuming you can get above the poisonous clouds of sulphuric acid, you could walk outside a floating colony in regular clothes, without a pressure suit. You’d need a source of breathable air, though.

Even better, breathable air is a lifting gas in the cloud tops of Venus. You could imagine a future colony, filled with breathable air, floating around Venus. Because the gravity on Venus is roughly the same as Earth, humans wouldn’t suffer any of the side effects of microgravity. In fact, it might be the only place in the entire Solar System other than Earth where we don’t need to account for low gravity.

Now the day on Venus is incredibly long, 243 earth days, so if you stay over the same place the whole time it would be light for four months then dark for four months. Not ideal for solar power on a first glance, but Venus turns so slowly that even at the equator you could stay ahead of the sunset at a fast walk.

So if you have floating colonies it would take very little effort to stay constantly on the light side or dark side or near the twilight zone of the terminator. You are essentially living inside a blimp, so it may as well be mobile. And on the day side it would only take a few solar panels and some propellers to stay ahead. And since it is so close to the Sun, there’s plenty of solar power. What could you do with it?

The atmosphere itself would probably serve as a source of raw materials. Carbon is the basis for all life on Earth. We’ll need it for food and building materials in space. Floating factories could process the thick atmosphere of Venus, to extract carbon, oxygen, and other elements.

Heat resistant robots could be lowered down to the surface to gather minerals and then retrieved before they’re cooked to death.

Venus does have a high gravity, so launching rockets up into space back out of Venus’ gravity well will be expensive.

Over longer periods of time, future colonists might construct large solar shades to shield themselves from the scorching heat, and eventually, even start cooling the planet itself.

The next planet from the Sun is Earth, the best planet in the Solar System. One of the biggest advantages of our colonization efforts will be to get heavy industry off our planet and into space. Why pollute our atmosphere and rivers when there’s so much more space… in space.

Over time, more and more of the resource gathering will happen off world, with orbital power generation, asteroid mining, and zero gravity manufacturing. Earth’s huge gravity well means that it’s best to bring materials down to Earth, not carry them up to space.

However, the normal gravity, atmosphere and established industry of Earth will allow us to manufacture the lighter high tech goods that the rest of the Solar System will need for their own colonization efforts.

But we haven’t completely colonized Earth itself. Although we’ve spread across the land, we know very little about the deep ocean. Future colonies under the oceans will help us learn more about self-sufficient colonies, in extreme environments. The oceans on Earth will be similar to the oceans on Europa or Enceladus, and the lessons we learn here will teach us to live out there.

As we return to space, we’ll colonize the region around our planet. We’ll construct bigger orbital colonies in Low Earth Orbit, building on our lessons from the International Space Station.

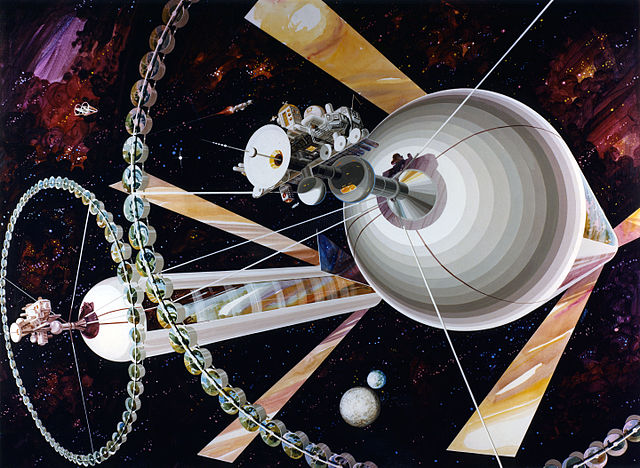

One of the biggest steps we need to take, is understanding how to overcome the debilitating effects of microgravity: the softened bones, weakened muscles and more. We need to perfect techniques for generating artificial gravity where there is none.

The best technique we have is rotating spacecraft to generate artificial gravity. Just like we saw in 2001, and The Martian, by rotating all or a portion of a spacecraft, you can generated an outward centrifugal force that mimics the acceleration of gravity. The larger the radius of the space station, the more comfortable and natural the rotation feels.

Low Earth Orbit also keeps a space station within the Earth’s protective magnetosphere, limiting the amount of harmful radiation that future space colonists will experience.

Other orbits are useful too, including geostationary orbit, which is about 36,000 kilometers above the surface of the Earth. Here spacecraft orbit the Earth at exactly the same rate as the rotation of Earth, which means that stations appear in fixed positions above our planet, useful for communication.

Geostationary orbit is higher up in Earth’s gravity well, which means these stations will serve a low-velocity jumping off points to reach other places in the Solar System. They’re also outside the Earth’s atmospheric drag, and don’t require any orbital boosting to keep them in place.

By perfecting orbital colonies around Earth, we’ll develop technologies for surviving in deep space, anywhere in the Solar System. The same general technology will work anywhere, whether we’re in orbit around the Moon, or out past Pluto.

When the technology is advanced enough, we might learn to build space elevators to carry material and up down from Earth’s gravity well. We could also build launch loops, electromagnetic railguns that launch material into space. These launch systems would also be able to loft supplies into transfer trajectories from world to world throughout the Solar System.

Earth orbit, close to the homeworld gives us the perfect place to develop and perfect the technologies we need to become a true spacefaring civilization. Not only that, but we’ve got the Moon.

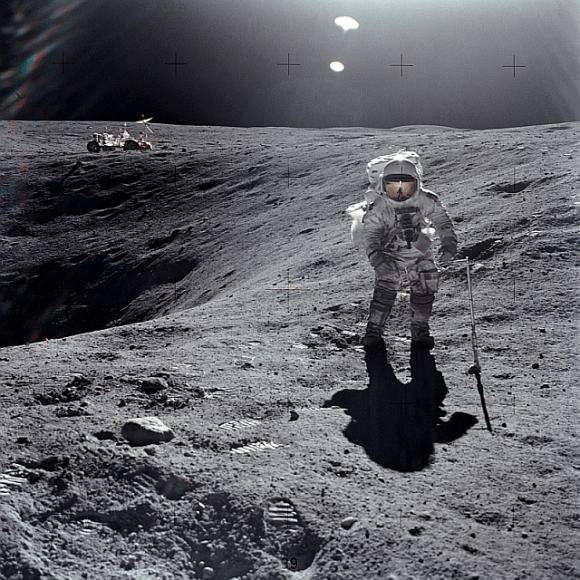

The Moon, of course, is the Earth’s only natural satellite, which orbits us at an average distance of about 400,000 kilometers. Almost ten times further than geostationary orbit.

The Moon takes a surprising amount of velocity to reach from Low Earth Orbit. It’s close, but expensive to reach, thrust speaking.

But that fact that it’s close makes the Moon an ideal place to colonize. It’s close to Earth, but it’s not Earth. It’s airless, bathed in harmful radiation and has very low gravity. It’s the place that humanity will learn to survive in the harsh environment of space.

But it still does have some resources we can exploit. The lunar regolith, the pulverized rocky surface of the Moon, can be used as concrete to make structures. Spacecraft have identified large deposits of water at the Moon’s poles, in its permanently shadowed craters. As with Mercury, these would make ideal locations for colonies.

Our spacecraft have also captured images of openings to underground lava tubes on the surface of the Moon. Some of these could be gigantic, even kilometers high. You could fit massive cities inside some of these lava tubes, with room to spare.

Helium-3 from the Sun rains down on the surface of the Moon, deposited by the Sun’s solar wind, which could be mined from the surface and provide a source of fuel for lunar fusion reactors. This abundance of helium could be exported to other places in the Solar System.

The far side of the Moon is permanently shadowed from Earth-based radio signals, and would make an ideal location for a giant radio observatory. Telescopes of massive size could be built in the much lower lunar gravity.

We talked briefly about an Earth-based space elevator, but an elevator on the Moon makes even more sense. With the lower gravity, you can lift material off the surface and into lunar orbit using cables made of materials we can manufacture today, such as Zylon or Kevlar.

One of the greatest threats on the Moon is the dusty regolith itself. Without any kind of weathering on the surface, these dust particles are razor sharp, and they get into everything. Lunar colonists will need very strict protocols to keep the lunar dust out of their machinery, and especially out of their lungs and eyes, otherwise it could cause permanent damage.

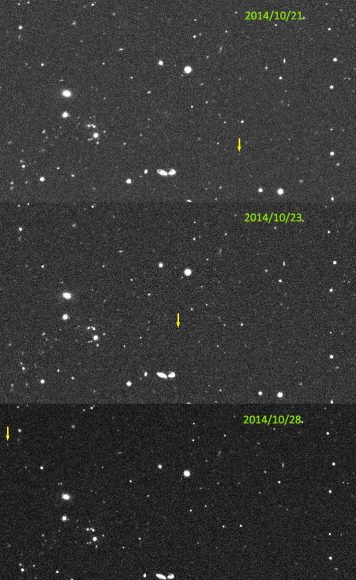

Although the vast majority of asteroids in the Solar System are located in the main asteroid belt, there are still many asteroids orbiting closer to Earth. These are known as the Near Earth Asteroids, and they’ve been the cause of many of Earth’s great extinction events.

These asteroids are dangerous to our planet, but they’re also an incredible resource, located close to our homeworld.

The amount of velocity it takes to get to some of these asteroids is very low, which means travel to and from these asteroids takes little energy. Their low gravity means that extracting resources from their surface won’t take a tremendous amount of energy.

And once the orbits of these asteroids are fully understood, future colonists will be able to change the orbits using thrusters. In fact, the same system they use to launch minerals off the surface would also push the asteroids into safer orbits.

These asteroids could be hollowed out, and set rotating to provide artificial gravity. Then they could be slowly moved into safe, useful orbits, to act as space stations, resupply points, and permanent colonies.

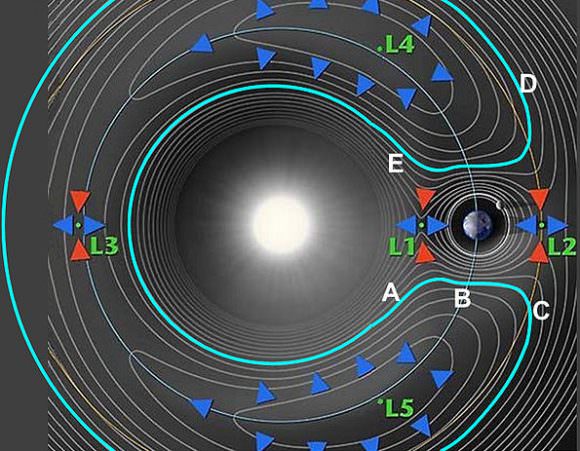

There are also gravitationally stable points at the Sun-Earth L4 and L5 Lagrange Points. These asteroid colonies could be parked there, giving us more locations to live in the Solar System.

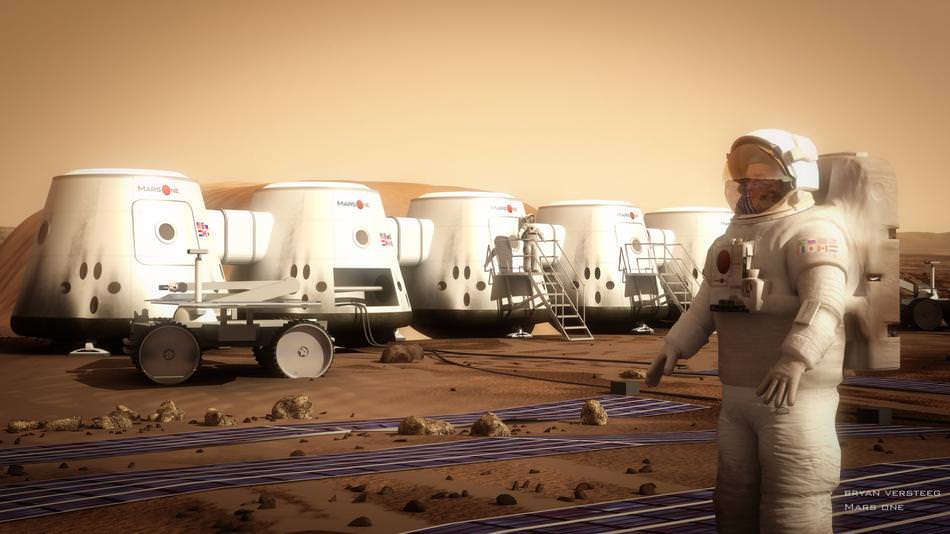

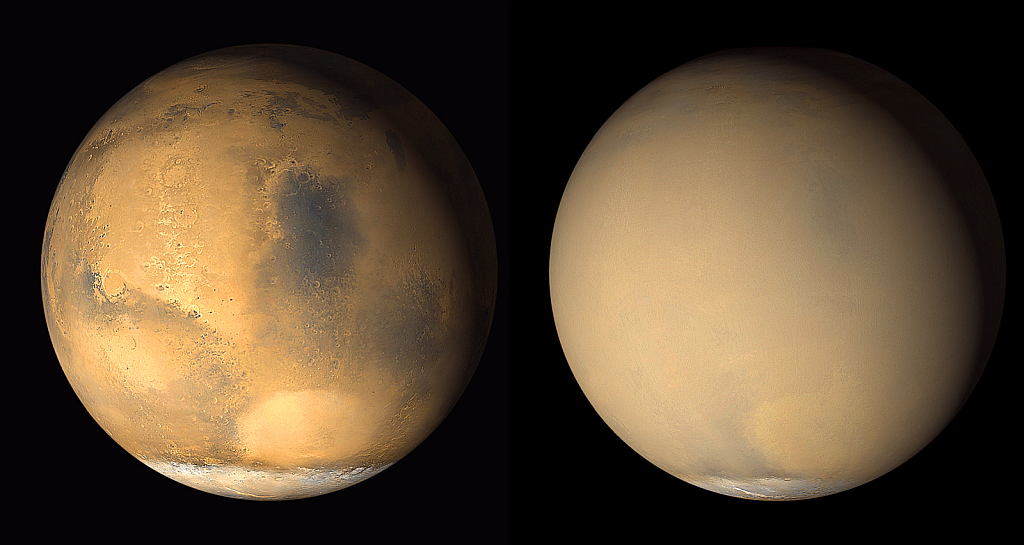

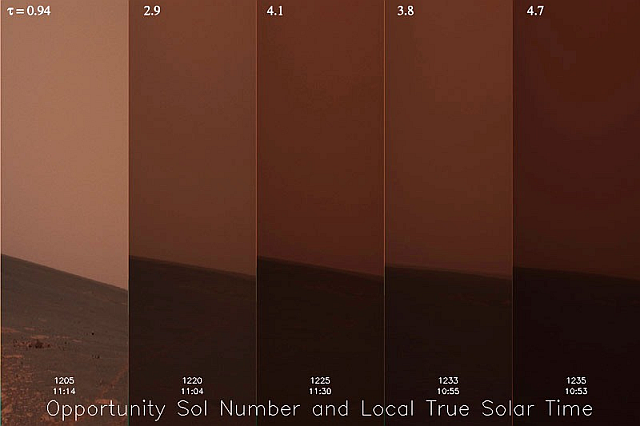

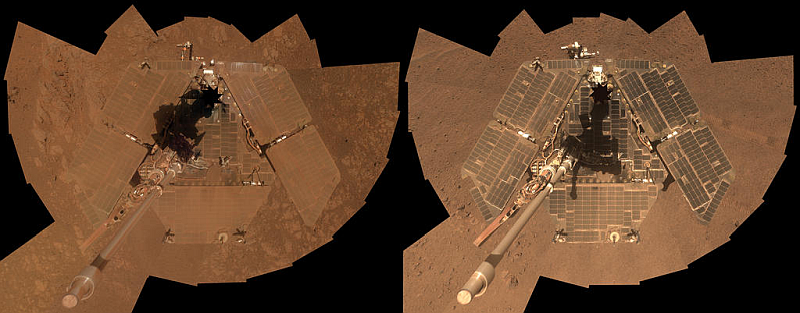

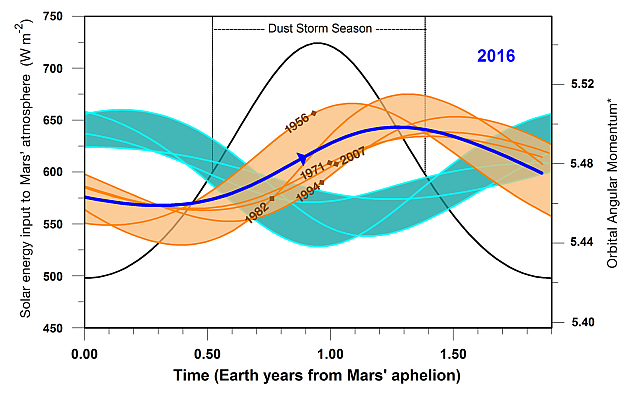

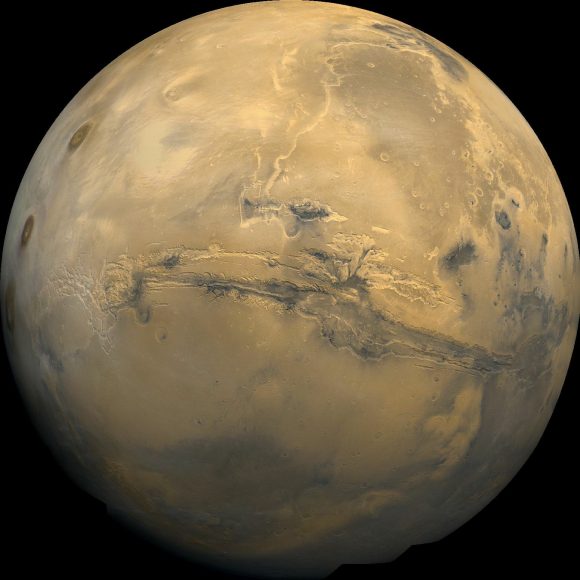

The future of humanity will include the colonization of Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun. On the surface, Mars has a lot going for it. A day on Mars is only a little longer than a day on Earth. It receives sunlight, unfiltered through the thin Martian atmosphere. There are deposits of water ice at the poles, and under the surface across the planet.

Martian ice will be precious, harvested from the planet and used for breathable air, rocket fuel and water for the colonists to drink and grow their food. The Martian regolith can be used to grow food. It does have have toxic perchlorates in it, but that can just be washed out.

The lower gravity on Mars makes it another ideal place for a space elevator, ferrying goods up and down from the surface of the planet.

Unlike the Moon, Mars has a weathered surface. Although the planet’s red dust will get everywhere, it won’t be toxic and dangerous as it is on the Moon.

Like the Moon, Mars has lava tubes, and these could be used as pre-dug colony sites, where human Martians can live underground, protected from the hostile environment.

Mars has two big problems that must be overcome. First, the gravity on Mars is only a third that of Earth’s, and we don’t know the long term impact of this on the human body. It might be that humans just can’t mature properly in the womb in low gravity.

Researchers have proposed that Mars colonists might need to spend large parts of their day on rotating centrifuges, to simulate Earth gravity. Or maybe humans will only be allowed to spend a few years on the surface of Mars before they have to return to a high gravity environment.

The second big challenge is the radiation from the Sun and interstellar cosmic rays. Without a protective magnetosphere, Martian colonists will be vulnerable to a much higher dose of radiation. But then, this is the same challenge that colonists will face anywhere in the entire Solar System.

That radiation will cause an increased risk of cancer, and could cause mental health issues, with dementia-like symptoms. The best solution for dealing with radiation is to block it with rock, soil or water. And Martian colonists, like all Solar System colonists will need to spend much of their lives underground or in tunnels carved out of rock.

In addition to Mars itself, the Red Planet has two small moons, Phobos and Deimos. These will serve as ideal places for small colonies. They’ll have the same low gravity as asteroid colonies, but they’ll be just above the gravity well of Mars. Ferries will travel to and from the Martian moons, delivering fresh supplies and sending Martian goods out to the rest of the Solar System.

We’re not certain yet, but there are good indicators these moons might have ice inside them, if so that is an excellent source of fuel and could make initial trips to Mars much easier by allowing us to send a first expedition to those moons, who then begin producing fuel to be used to land on Mars and to leave Mars and return home.

According to Elon Musk, if a Martian colony can reach a million inhabitants, it’ll be self-sufficient from Earth or any other world. At that point, we would have a true, Solar System civilization.

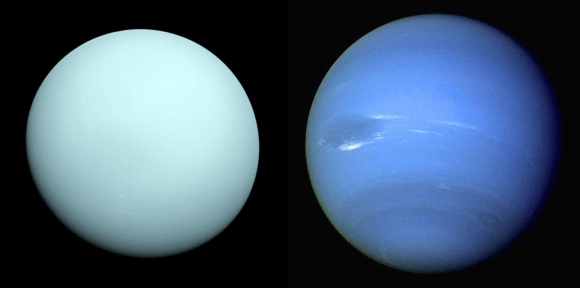

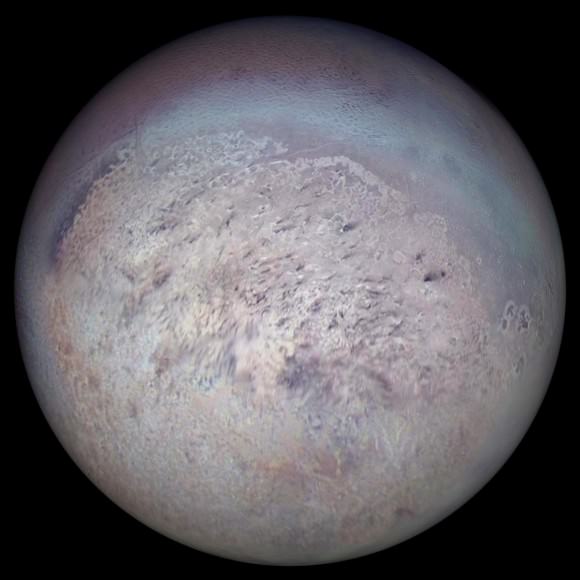

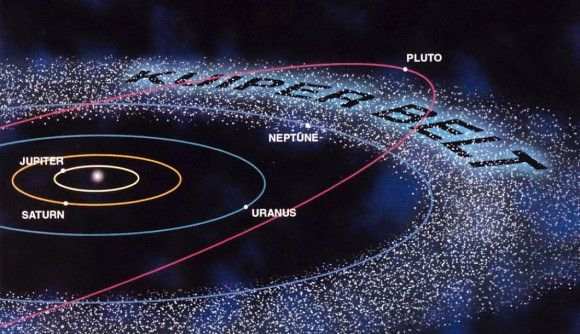

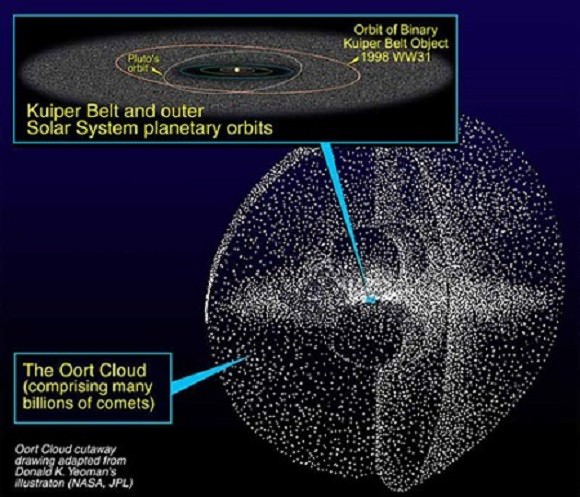

Now, continue on to the other half of this article, written by Isaac Arthur, where he talks about what it will take to colonize the outer Solar System. Where water ice is plentiful but solar power is feeble. Where travel times and energy require new technologies and techniques to survive and thrive.