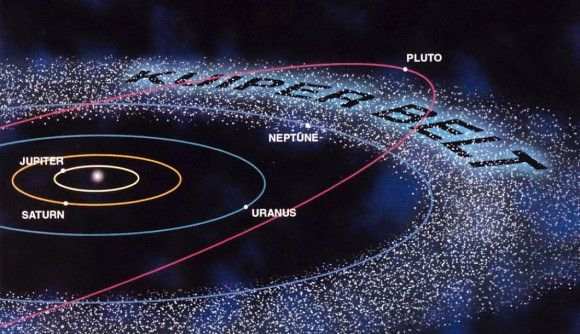

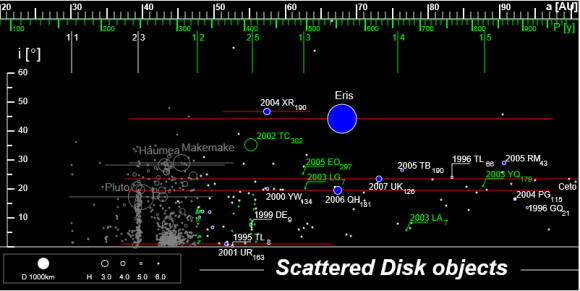

The Solar System is pretty huge place, extending from our Sun at the center all the way out to the Kuiper Cliff – a boundary within the Kuiper Belt that is located 50 AU from the Sun. As a rule, the farther one ventures from the Sun, the colder and more mysterious things get. Whereas temperatures in the inner Solar System are enough to burn you alive or melt lead, beyond the “Frost Line“, they get cold enough to freeze volatiles like ammonia and methane.

So what is the coldest planet of our Solar System? In the past, the title for “most frigid body” went to Pluto, as it was the farthest then-designated planet from the Sun. However, due to the IAU’s decision in 2006 to reclassify Pluto as a “dwarf planet”, the title has since passed to Neptune. As the eight planet from our Sun, it is now the outermost planet in the Solar System, and hence the coldest.

Orbit and Distance:

With an average distance (semi-major axis) of 4,504,450,000 km (2,798,935,466.87 mi or 30.11 AU), Neptune is the farthest planet from the Sun. The planet has a very minor eccentricity of 0.0086, which means that its orbit around the Sun varies from a distance of 29.81 AU (4.459 x 109 km) at perihelion to 30.33 AU (4.537 x 109 km) at aphelion.

Because Neptune’s axial tilt (28.32°) is similar to that of Earth (~23°) and Mars (~25°), the planet experiences similar seasonal changes. Combined with its long orbital period, this means that the seasons last for forty Earth years. Also owing to its axial tilt being comparable to Earth’s is the fact that the variation in the length of its day over the course of the year is not any more extreme than it is on Earth.

Average Temperature:

When it comes to ascertaining the average temperature of a planet, scientists rely on temperature variations measured from the surface. As a gas/ice giant, Neptune has no surface, per se. As a result, scientists rely on temperature readings from where the atmospheric pressure is equal to 1 bar (100 kPa), the equivalent to atmospheric pressure at sea level here on Earth.

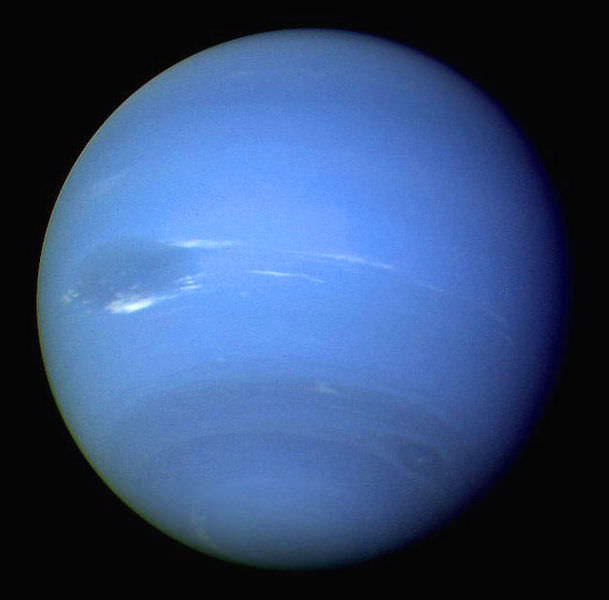

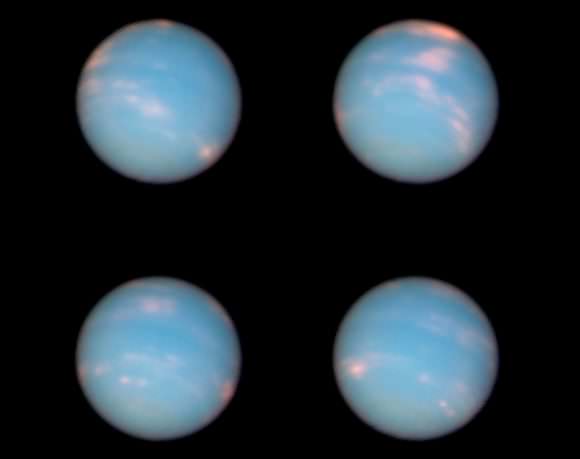

On Neptune, this area of the atmosphere is just below the upper level clouds. Pressures in this region range between 1 and 5 bars (100 – 500 kPa), and temperature reach a high of 72 K (-201.15 °C; -330 °F). At this temperature, conditions are suitable for methane to condense, and clouds of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide are thought to form (which is what gives Neptune its characteristically dark cyan coloring).

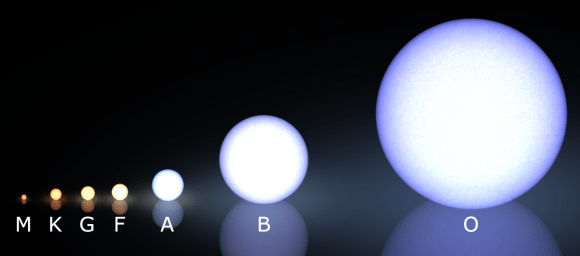

Farther into space, where pressures drop to about 0.1 bars (10 kPa), temperatures decrease to their low of around 55 K (-218 °C; -360 °F). Further into the planet, pressures increase dramatically, which also leads to a dramatic increase in temperature. At its core, Neptune reaches temperatures of up to 7273 K (7000 °C; 12632 °F), which is comparable to the surface of the Sun.

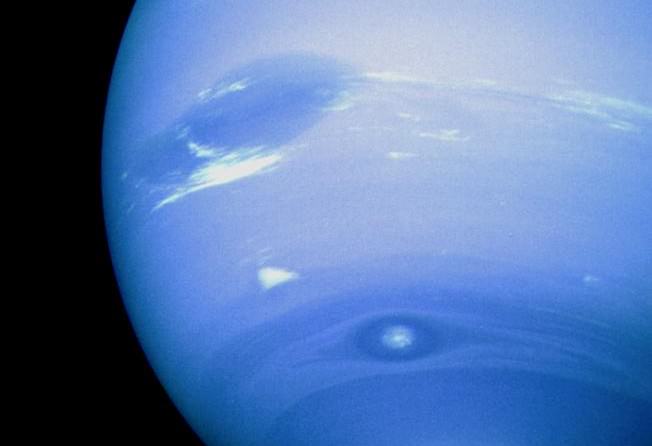

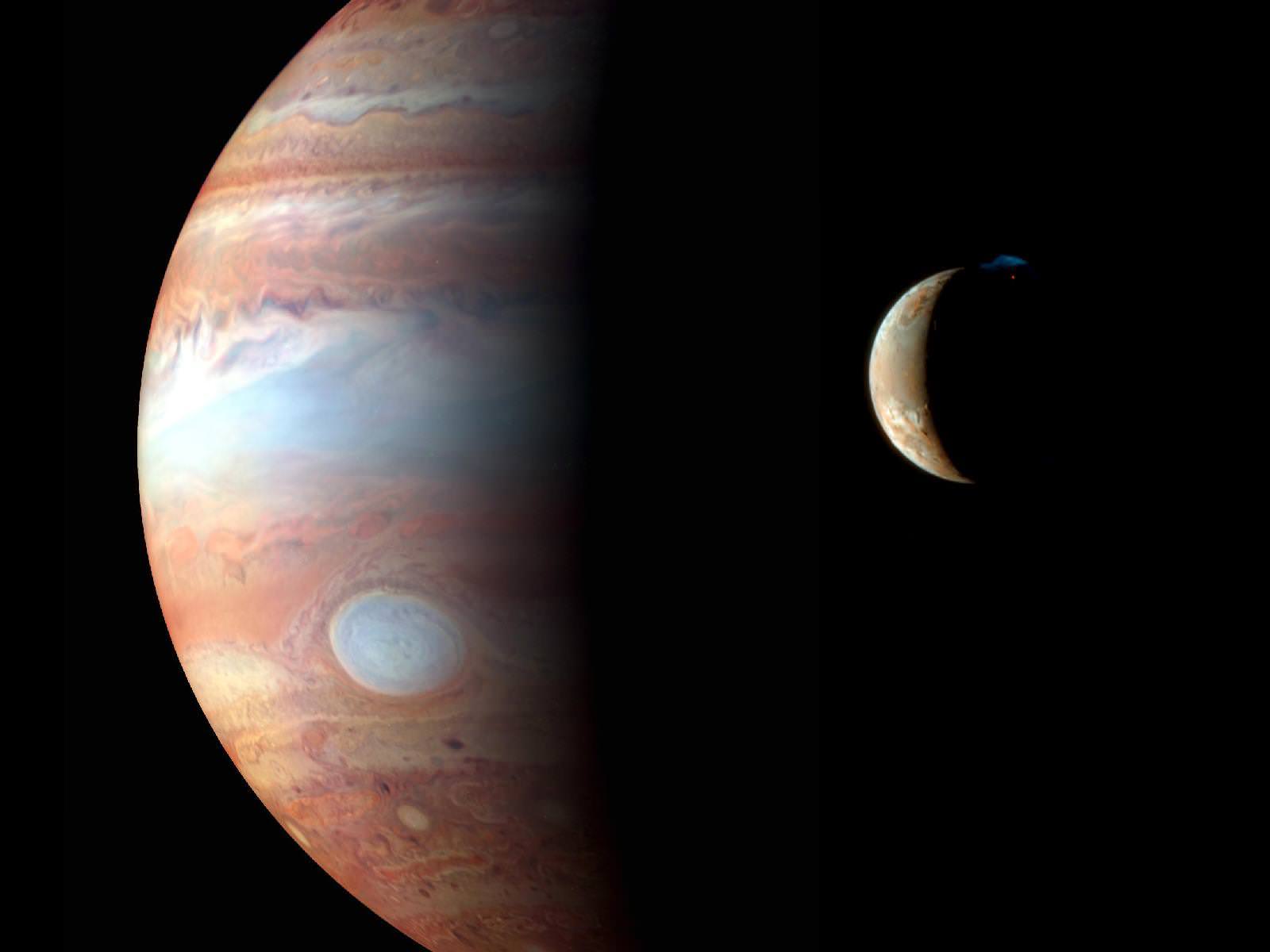

The huge temperature differences between Neptune’s center and its surface (along with its differential rotation) create huge wind storms, which can reach as high as 2,100 km/hour, making them the fastest in the Solar System. The first to be spotted was a massive anticyclonic storm measuring 13,000 x 6,600 km and resembling the Great Red Spot of Jupiter.

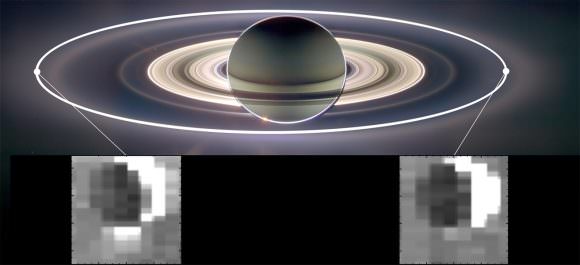

Known as the Great Dark Spot, this storm was not spotted five later (Nov. 2nd, 1994) when the Hubble Space Telescope looked for it. Instead, a new storm that was very similar in appearance was found in the planet’s northern hemisphere, suggesting that these storms have a shorter lifespan than Jupiter’s. The Scooter is another storm, a white cloud group located farther south than the Great Dark Spot.

This nickname first arose during the months leading up to the Voyager 2 encounter in 1989, when the cloud group was observed moving at speeds faster than the Great Dark Spot. The Small Dark Spot, a southern cyclonic storm, was the second-most-intense storm observed during the 1989 encounter. It was initially completely dark; but as Voyager 2 approached the planet, a bright core developed and could be seen in most of the highest-resolution images.

Temperature Anomalies:

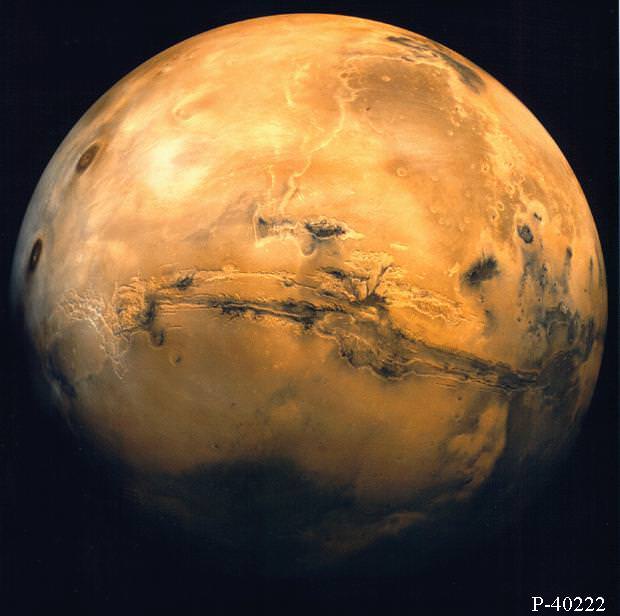

Despite being 50% further from the Sun than Uranus – which orbits the Sun at an average distance of 2,875,040,000 km (1,786,467,032.5 mi or 19.2184 AU) – Neptune receives only 40% of the solar radiation that Uranus does. In spite of that, the two planets’ surface temperatures are surprisingly close, with Uranus experiencing an average “surface” temperature of 76 K (-197.2 °C)

And while temperatures similarly increase the further one ventures into the core, the discrepancy is larger. Uranus only radiates 1.1 times as much energy as it receives from the Sun, whereas Neptune radiates about 2.61 times as much. Neptune is the farthest planet from the Sun, yet its internal energy is sufficient to drive the fastest planetary winds seen in the Solar System.

One would expect Neptune to be much colder than Uranus, and the mechanism for this remains unknown. However, astronomers have theorized that Neptune’s higher internal temperature (and the exchange of heat between the core and outer layers) might be the reason for why Neptune isn’t significantly colder than Uranus.

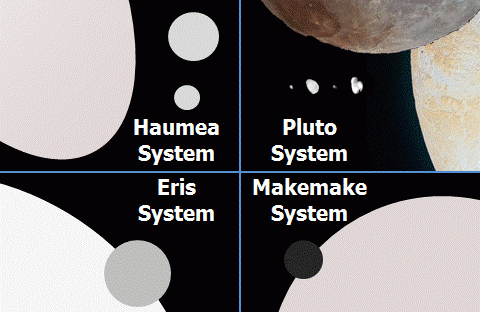

As already noted, Pluto’s surface temperatures do get to being lower than Neptune’s. Between its greater distance from the Sun, and the fact that it is not a gas/ice giant (so therefore doesn’t have extreme temperatures at its core) means that it experiences temperatures between a high of 55 K (-218 °C; -360 °F)and a low of 33 K (-240 °C; -400 °F). However, since it is no longer classified as a planet (but a dwarf planet, TNO, KBO, plutoid, etc.) it is no longer in the running. Sorry, Pluto!

We’ve written many articles about Neptune here at Universe Today. Here’s Who Discovered Neptune?, What is the Surface Temperature of Neptune?, What is the Surface of Neptune Like?, 10 Interesting Facts about Neptune, The Rings of Neptune, How Many Moons Does Neptune Have?

If you’d like more information on Neptune, take a look at Hubblesite’s News Releases about Neptune, and here’s a link to NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Neptune.

We’ve also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast all about Neptune. Listen here, Episode 63: Neptune.