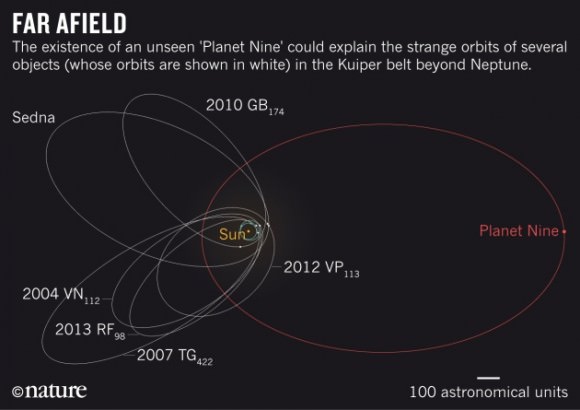

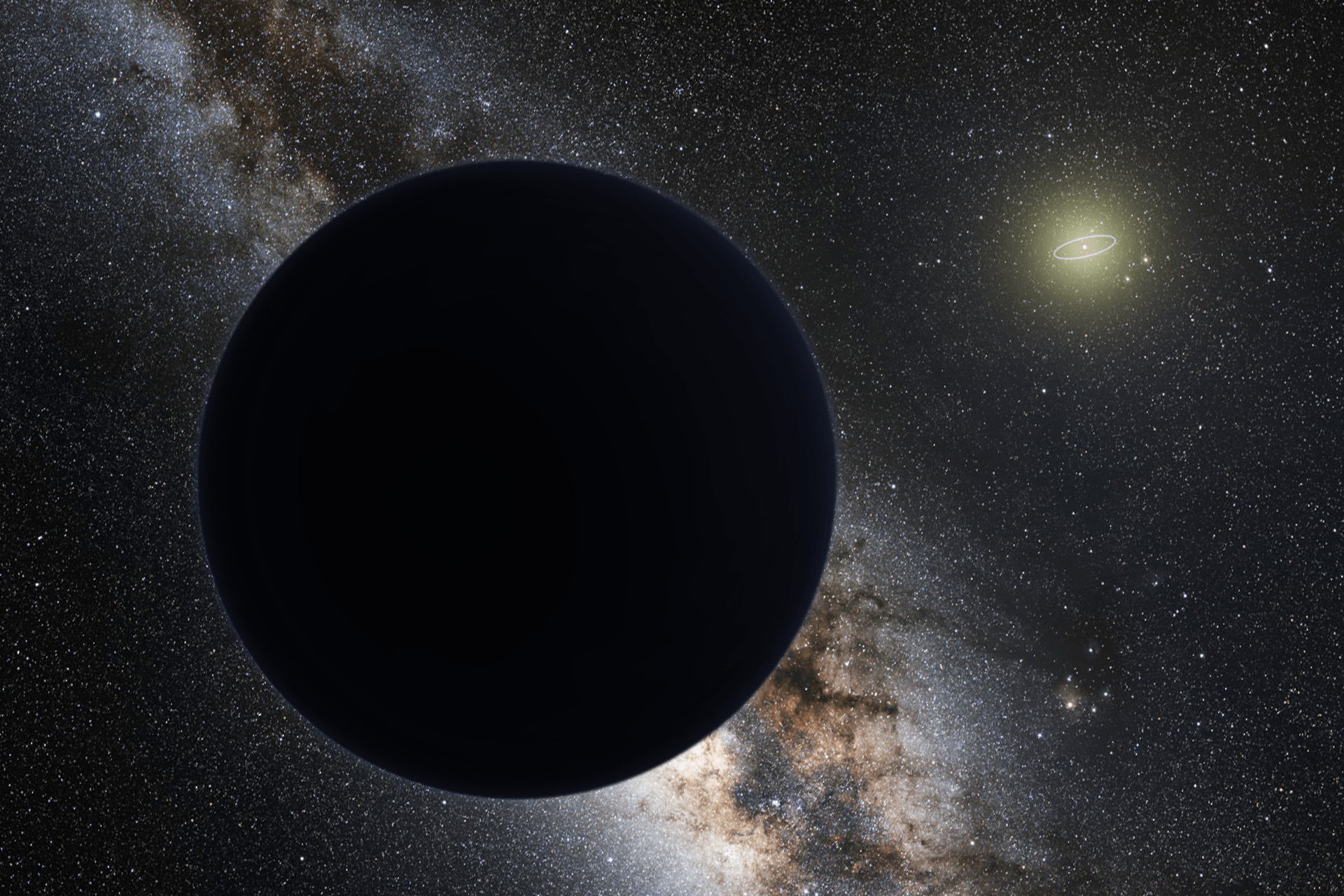

Finding a ninth planet in our Solar System this late in the game would be fascinating. It would also be somewhat of a surprise, considering our observational capabilities. But new evidence, in the form of small perturbations in the orbit of the Cassini probe, points to the existence of an as-yet undetected planet in our solar system.

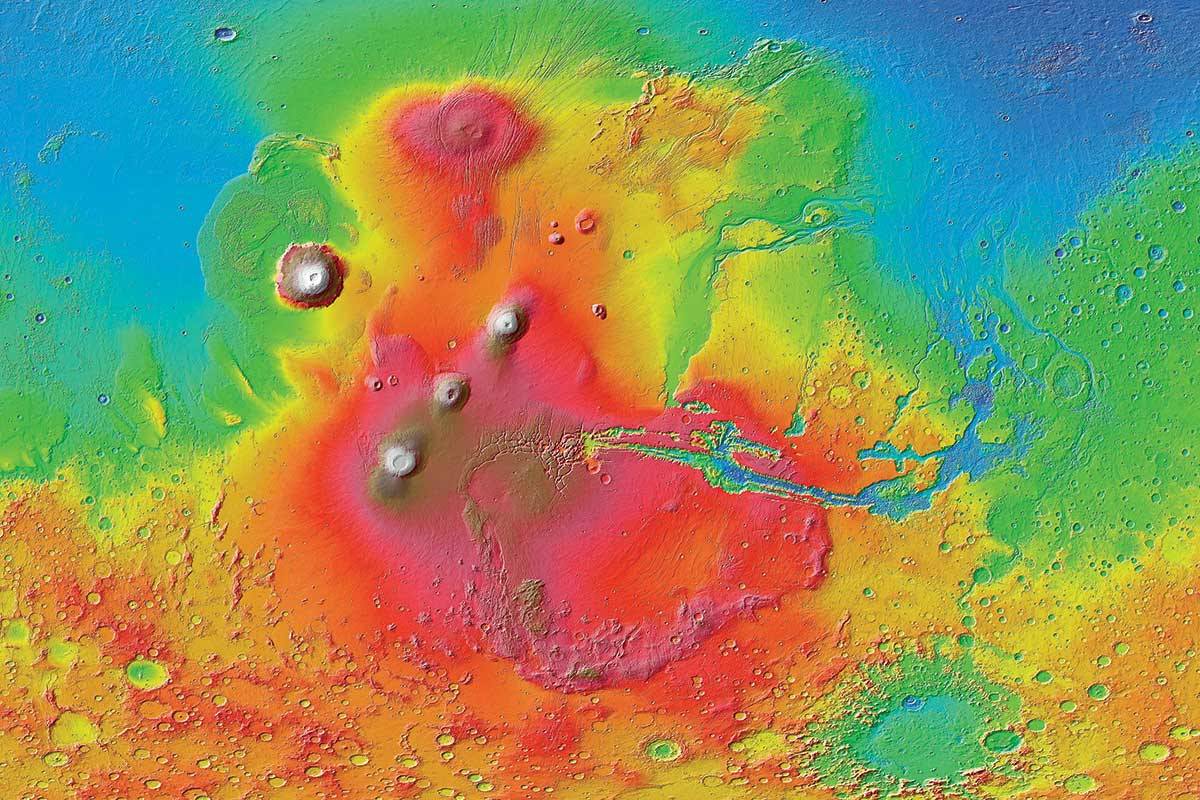

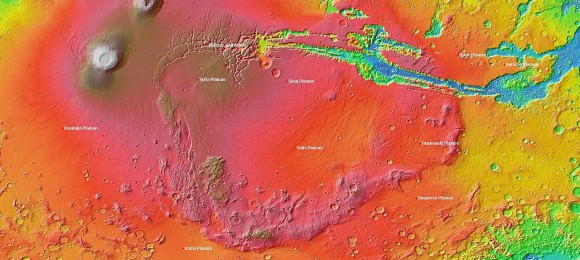

Back in January, Konstantin Batygin and Mike Brown, two planetary scientists from the California Institute of Technology, presented evidence supporting the existence of a ninth planet. Their paper showed that some Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) display unexpected behaviour. It appears that 6 KBOs are affected by their relationship to a large object, but the KBOs in question are too distant from the known gas giants for them to be responsible. They think that a large, distant planet, in the distant reaches of our Solar System, could be responsible for the unexpected orbital clustering of these KBOs.

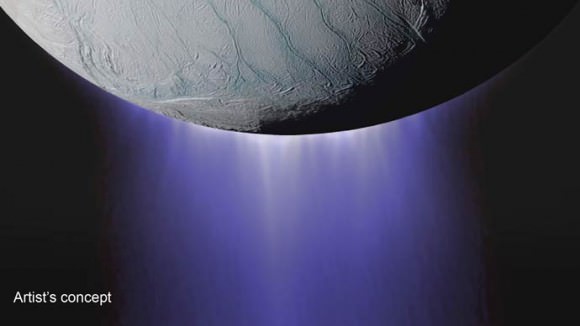

Now, the Ninth Planet idea is gaining steam, and another team of researchers have presented evidence that small perturbations in the orbit of the Cassini spacecraft are caused by the new planet. Agnès Fienga at the Côte d’Azur Observatory in France, and her colleagues, have been working on a detailed model of the Solar System for over a decade. They plugged the hypothetical orbit and size of Planet Nine into their model, to see if it fit.

Planet Nine is calculated to be about 4 times as large as Earth, and 10 times as massive. It’s orbit takes between 10,000 and 20,000 years. A planet that large can only be hiding in so many places, and those places are a long way from Earth. Fienga found a potential home for Planet Nine, some 600 astronomical units (AU) from here. That much mass at that location could account for the perturbations in Cassini’s orbit.

There’s more good news when it comes to Planet Nine. By happy accident, it’s predicted location in the sky is towards the constellation Cetus, in the southern hemisphere. This means that it is in the view of the Dark Energy Survey, a southern hemisphere project that is studying the acceleration of the universe. The Dark Energy Survey is not designed to search for planetary objects, but it has successfully found at least one icy object.

There are other ways that the existence of Planet Nine could be confirmed. If it’s as large as thought, then it will radiate enough internal heat to be detected by instruments designed to study the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). There is also an enormous amount of data from multiple experiments and observations done over the years that might contain an inadvertent clue. But looking through it is an enormous task.

As for Brown and Batygin, who initially proposed the existence of Planet Nine based on the behaviour of KBOs, they are already proposing a more specific hunt for the elusive planet. They have asked for a substantial amount of observing time at the Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii, in order to examine closely the location that Fienga’s solar system model predicts Planet Nine to be at.

For a more detailed look at Batygin’s and Brown’s work analyzing KBOs, read Matt Williams’ article here.

Martian Eye Candy: A beautiful picture of some dunes on the surface of Mars. Thanks MRO! (Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)

Martian Eye Candy: A beautiful picture of some dunes on the surface of Mars. Thanks MRO! (Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)