While there are untold billions of celestial objects visible in the nighttime sky, some of them are better known than others. Most of these are stars that are visible to the naked eye and very bright compared to other stellar objects. For this reason, most of them have a long history of being observed and studied by human beings, and most likely occupy an important place in ancient folklore.

So without further ado, here is a sampling of some of the better-known stars in that are visible in the nighttime sky:

Polaris:

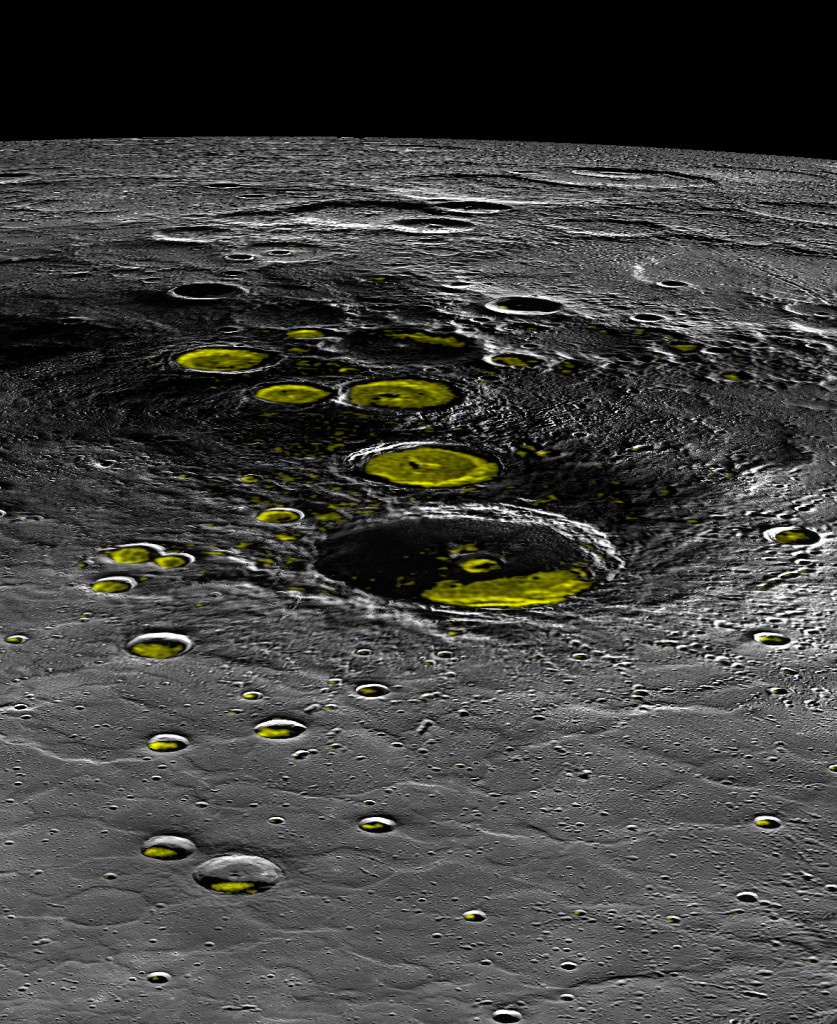

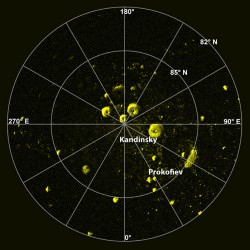

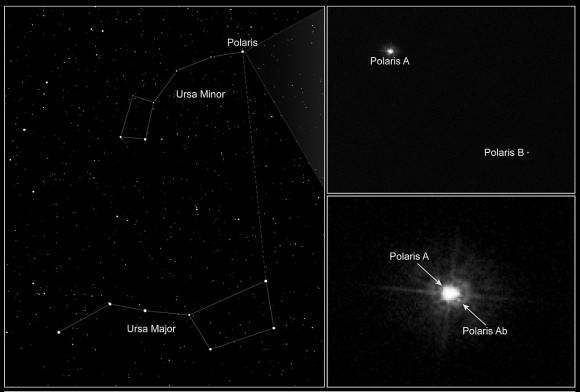

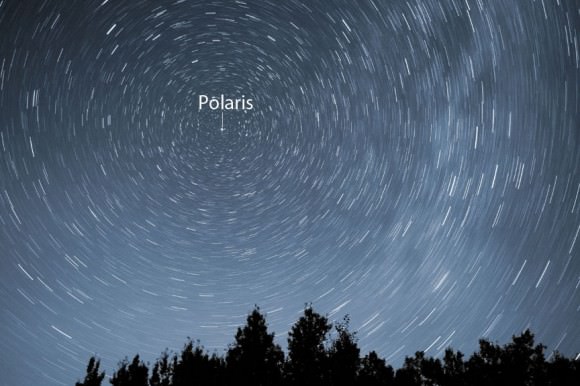

Also known as the North Star (as well as the Pole Star, Lodestar, and sometimes Guiding Star), Polaris is the 45th brightest star in the night sky. It is very close to the north celestial pole, which is why it has been used as a navigational tool in the northern hemisphere for centuries. Scientifically speaking, this star is known as Alpha Ursae Minoris because it is the alpha star in the constellation Ursa Minor (the Little Bear).

It’s more than 430 light-years away from Earth, but its luminosity (being a white supergiant) makes it highly visible to us here on Earth. What’s more, rather than being a single supergiant, Polaris is actually a trinary star system, comprised of a main star (alpha UMi Aa) and two smaller companions (alpha UMi B, alpha UMi Ab). These, along with its two distant components (alpha UMi C, alpha UMi D), make it a multistar system.

Interestingly enough, Polaris wasn’t always the north star. That’s because Earth’s axis wobbles over thousands of years and points in different directions. But until such time as Earth’s axis moves farther away from the “Polestar”, it remains our guide.

Because it is what is known as a Cepheid variable star – i.e. a star that pulsates radially, varying in both temperature and diameter to produce brightness changes – it’s distance to our Sun has been the subject of revision. Many scientific papers suggest that it may be up to 30% closer to our Solar System than previously expected – putting it in the vicinity of 238 light years away.

Sirius:

Also known as the Dog Star, because it’s the brightest star in Canis Major (the “Big Dog”), Sirius is also the brightest star in the night sky. The name “Sirius” is derived from the Ancient Greek “Seirios“, which translates to “glowing” or “scorcher”. Whereas it appears to be a single bright star to the naked eye, Sirius is actually a binary star system, consisting of a white main-sequence star named Sirius A, and a faint white dwarf companion named Sirius B.

The reason why it is so bright in the sky is due to a combination of its luminosity and distance – at 6.8 light years, it is one of Earth’s nearest neighbors. And in truth, it is actually getting closer. For the next 60,000 years or so, astronomers expect that it will continue to approach our Solar System; at which point, it will begin to recede again.

In ancient Egypt, it was seen as a signal that the flooding of the Nile was close at hand. For the Greeks, the rising of Sirius in the night sky was a sign of the”dog days of summer”. To the Polynesians in the southern hemisphere, it marked the approach of winter and was an important star for navigation around the Pacific Ocean.

Alpha Centauri System:

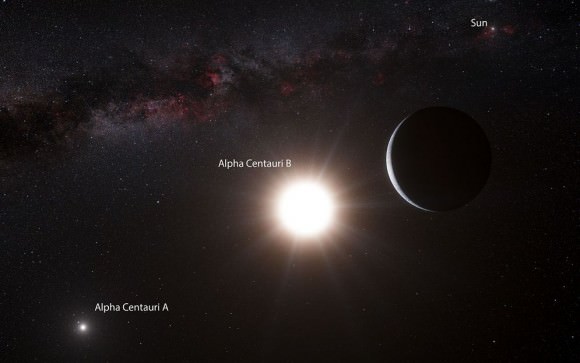

Also known as Rigel Kent or Toliman, Alpha Centauri is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Centaurus and the third brightest star in the night sky. It is also the closest star system to Earth, at just a shade over four light-years. But much like Sirius and Polaris, it is actually a multistar system, consisting of Alpha Centauri A, B, and Proxima Centauri (aka. Centauri C).

Based on their spectral classifications, Alpha Centauri A is a main sequence white dwarf with roughly 110% of the mass and 151.9% the luminosity of our Sun. Alpha Centauri B is an orange subgiant with 90.7% of the Sun’s mass and 44.5% of its luminosity. Proxima Centauri, the smallest of the three, is a red dwarf roughly 0.12 times the mass of our Sun, and which is the closest of the three to our Solar System.

English explorer Robert Hues was the first European to make a recorded mention of Alpha Centauri, which he did in his 1592 work Tractatus de Globis. In 1689, Jesuit priest and astronomer Jean Richaud confirmed the existence of a second star in the system. Proxima Centauri was discovered in 1915 by Scottish astronomer Robert Innes, Director of the Union Observatory in Johannesburg, South Africa.

In 2012, astronomers discovered an Earth-sized planet around Alpha Centauri B. Known as Alpha Centauri Bb, it’s close proximity to its parent star likely means that it is too hot to support life.

Betelgeuse:

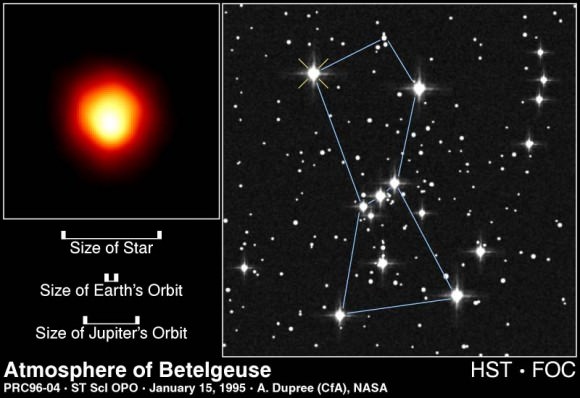

Pronounced “Beetle-juice” (yes, the same as the 1988 Tim Burton movie), this bright red supergiant is roughly 65o light-year from Earth. Also known as Alpha Orionis, it is nevertheless easy to spot in the Orion constellation since it is one of the largest and most luminous stars in the night sky.

The star’s name is derived from the Arabic name Ibt al-Jauza’, which literally means “the hand of Orion”. In 1985, Margarita Karovska and colleagues from the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, announced the discovery of two close companions orbiting Betelgeuse. While this remains unconfirmed, the existence of possible companions remains an intriguing possibility.

What excites astronomers about Betelgeuse is it will one day go supernova, which is sure to be a spectacular event that people on Earth will be able to see. However, the exact date of when that might happen remains unknown.

Rigel:

Also known as Beta Orionis, and located between 700 and 900 light years away, Rigel is the brightest star in the constellation Orion and the seventh brightest star in the night sky. Here too, what appears to be a blue supergiant is actually a multistar system. The primary star (Rigel A) is a blue-white supergiant that is 21 times more massive than our sun, and shines with approximately 120,000 times the luminosity.

Rigel B is itself a binary system, consisting of two main sequence blue-white subdwarf stars. Rigel B is the more massive of the pair, weighing in at 2.5 Solar masses versus Rigel C’s 1.9. Rigel has been recognized as being a binary since at least 1831 when German astronomer F.G.W. Struve first measured it. A fourth star in the system has been proposed, but it is generally considered that this is a misinterpretation of the main star’s variability.

Rigel A is a young star, being only 10 million years old. And given its size, it is expected to go supernova when it reaches the end of its life.

Vega:

Vega is another bright blue star that anchors the otherwise faint Lyra constellation (the Harp). Along with Deneb (from Cygnus) and Altair (from Aquila), it is a part of the Summer Triangle in the Northern hemisphere. It is also the brightest star in the constellation Lyra, the fifth brightest star in the night sky and the second brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere (after Arcturus).

Characterized as a white dwarf star, Vega is roughly 2.1 times as massive as our Sun. Together with Arcturus and Sirius, it is one of the most luminous stars in the Sun’s neighborhood. It is a relatively close star at only 25 light-years from Earth.

Vega was the first star other than the Sun to be photographed and the first to have its spectrum recorded. It was also one of the first stars whose distance was estimated through parallax measurements, and has served as the baseline for calibrating the photometric brightness scale. Vega’s extensive history of study has led it to be termed “arguably the next most important star in the sky after the Sun.”

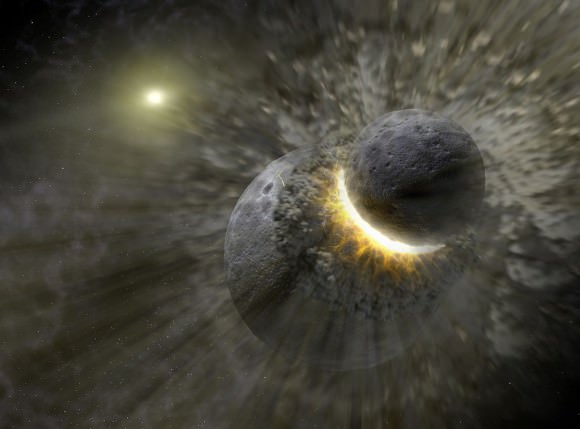

Based on observations that showed excess emission of infrared radiation, Vega is believed to have a circumstellar disk of dust. This dust is likely to be the result of collisions between objects in an orbiting debris disk. For this reason, stars that display an infrared excess because of circumstellar dust are termed “Vega-like stars”.

Thousands of years ago, (ca. 12,000 BCE) Vega was used as the North Star is today, and will be so again around the year 13,727 CE.

Pleiades:

Also known as the “Seven Sisters”, Messier 45 or M45, Pleiades is actually an open star cluster located in the constellation of Taurus. At an average distance of 444 light years from our Sun, it is one of the nearest star clusters to Earth, and the most visible to the naked eye. Though the seven largest stars are the most apparent, the cluster actually consists of over 1,000 confirmed members (along with several unconfirmed binaries).

The core radius of the cluster is about 8 light years across, while it measures some 43 light years at the outer edges. It is dominated by young, hot blue stars, though brown dwarfs – which are just a fraction of the Sun’s mass – are believed to account for 25% of its member stars.

The age of the cluster has been estimated at between 75 and 150 million years, and it is slowly moving in the direction of the “feet” of what is currently the constellation of Orion. The cluster has had several meanings for many different cultures here on Earth, which include representations in Biblical, ancient Greek, Asian, and traditional Native American folklore.

Antares:

Also known as Alpha Scorpii, Antares is a red supergiant and one of the largest and most luminous observable stars in the nighttime sky. It’s name – which is Greek for “rival to Mars” (aka. Ares) – refers to its reddish appearance, which resembles Mars in some respects. It’s location is also close to the ecliptic, the imaginary band in the sky where the planets, Moon and Sun move.

This supergiant is estimated to be 17 times more massive, 850 times larger in terms of diameter, and 10,000 times more luminous than our Sun. Hence why it can be seen with the naked eye, despite being approximately 550 light-years from Earth. The most recent estimates place its age at 12 million years.

Antares is the seventeenth brightest star that can be seen with the naked eye and the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius. Along with Aldebaran, Regulus, and Fomalhaut, Antares comprises the group known as the ‘Royal stars of Persia’ – four stars that the ancient Persians (circa. 3000 BCE) believed guarded the four districts of the heavens.

Canopus:

Also known as Alpha Carinae, this white giant is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina and the second brightest star in the nighttime sky. Located over 300 light-years away from Earth, this star is named after the mythological Canopus, the navigator for king Menelaus of Sparta in The Iliad.

Thought it was not visible to the ancient Greeks and Romans, the star was known to the ancient Egyptians, as well as the Navajo, Chinese and ancient Indo-Aryan people. In Vedic literature, Canopus is associated with Agastya, a revered sage who is believed to have lived during the 6th or 7th century BCE. To the Chinese, Canopus was known as the “Star of the Old Man”, and was charted by astronomer Yi Xing in 724 CE.

It is also referred to by its Arabic name Suhayl (Soheil in persian), which was given to it by Islamic scholars in the 7th Century CE. To the Bedouin people of the Negev and Sinai, it was also known as Suhayl, and used along with Polaris as the two principal stars for navigation at night.

It was not until 1592 that it was brought to the attention of European observers, once again by Robert Hues who recorded his observations of it alongside Achernar and Alpha Centauri in his Tractatus de Globis (1592).

As he noted of these three stars, “Now, therefore, there are but three Stars of the first magnitude that I could perceive in all those parts which are never seene here in England. The first of these is that bright Star in the sterne of Argo which they call Canobus. The second is in the end of Eridanus. The third is in the right foote of the Centaure.”

This star is commonly used for spacecraft to orient themselves in space, since it is so bright compared to the stars surrounding it.

Universe Today has articles on what is the North Star and types of stars. Here’s another article about the 10 brightest stars. Astronomy Cast has an episode on famous stars.