After the tragic failure of the first Phobos-Grunt mission to even make it out of low-Earth orbit, the Russian space agency (Roscosmos) is hoping to give it another go at Mars’ largest moon with the Phobos-Grunt 2 mission in 2020. This new-and-improved version of the spacecraft will also feature a lander and return stage, and, if successful, may not only end up sending back pieces of Phobos but of Mars as well.

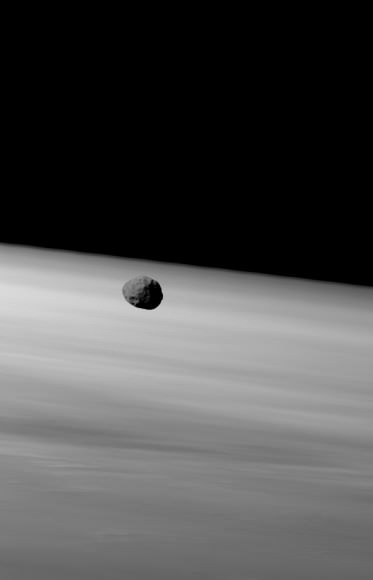

The origins of Phobos have long been a topic of planetary science debate. Did it form with Mars as a planet? Is it a wayward asteroid that ventured too closely to Mars? Or is it a chunk of the Red Planet blasted up into orbit from an ancient impact event? Only in-depth examination of its surface material will allow scientists to determine which scenario is most likely (or if the correct answer is really “none of the above”) and Russia’s ambitious Phobos-Grunt mission attempted to become the first ever to not only land on the 16-mile-wide moon but also send samples back to Earth.

Unfortunately it wasn’t in the cards. After launching on Nov. 9, 2011, Phobos-Grunt’s upper stage failed to ignite, stranding it in low-Earth orbit. After all attempts to re-establish communication and control of the ill-fated spacecraft failed, Phobos-Grunt crashed back to Earth on Jan. 15, impacting in the southern Pacific off the coast of Chile.

But with a decade of development already invested in the mission, Roscosmos is willing to try again. “Ad astra per aspera,” as it’s said, and Phobos-Grunt 2 will attempt to overcome all hardships in 2020 to do what its predecessor couldn’t.

Read more: Russia to Try Again for Phobos-Grunt?

And, according to participating researchers James Head and Kenneth Ramsley from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, the sample mission could end up being a “twofer.”

Orbiting at an altitude of only 5,840 miles (9,400 km) Phobos has been passing through plumes material periodically blown off of Mars by impact events. Its surface soil very likely contains a good amount of Mars itself, scooped up over the millennia.

“When an impactor hits Mars, only a certain of proportion of ejecta will have enough velocity to reach the altitude of Phobos, and Phobos’ orbital path intersects only a certain proportion of that,” said Ramsley, a visiting researcher in Brown’s planetary geosciences group. “So we can crunch those numbers and find out what proportion of material on the surface of Phobos comes from Mars.”

Determining that ratio would then help figure out where Phobos was in Mars orbit millions of years ago, which in turn could point at its origins.

“Only recently — in the last several 100 million years or so — has Phobos orbited so close to Mars,” Ramsley said. “In the distant past it orbited much higher up. So that’s why you’re going to see probably 10 to 100 times higher concentration in the upper regolith as opposed to deeper down.”

In addition, having an actual sample of Phobos (along with stowaway bits of Mars) in hand on Earth, as well as all the data acquired during the mission itself, would give scientists invaluable insight to the moon’s as-yet-unknown internal composition.

“Phobos has really low density,” said Head, professor of geological sciences at Brown and an author on the study. “Is that low density due to ice in its interior or is it due to Phobos being completely fragmented, like a loose rubble pile? We don’t know.”

The study was published in Volume 87 of Space and Planetary Science (Mars impact ejecta in the regolith of Phobos: Bulk concentration and distribution.)

Source: Brown University news release and RussianSpaceWeb.com.

See more images of Phobos here.