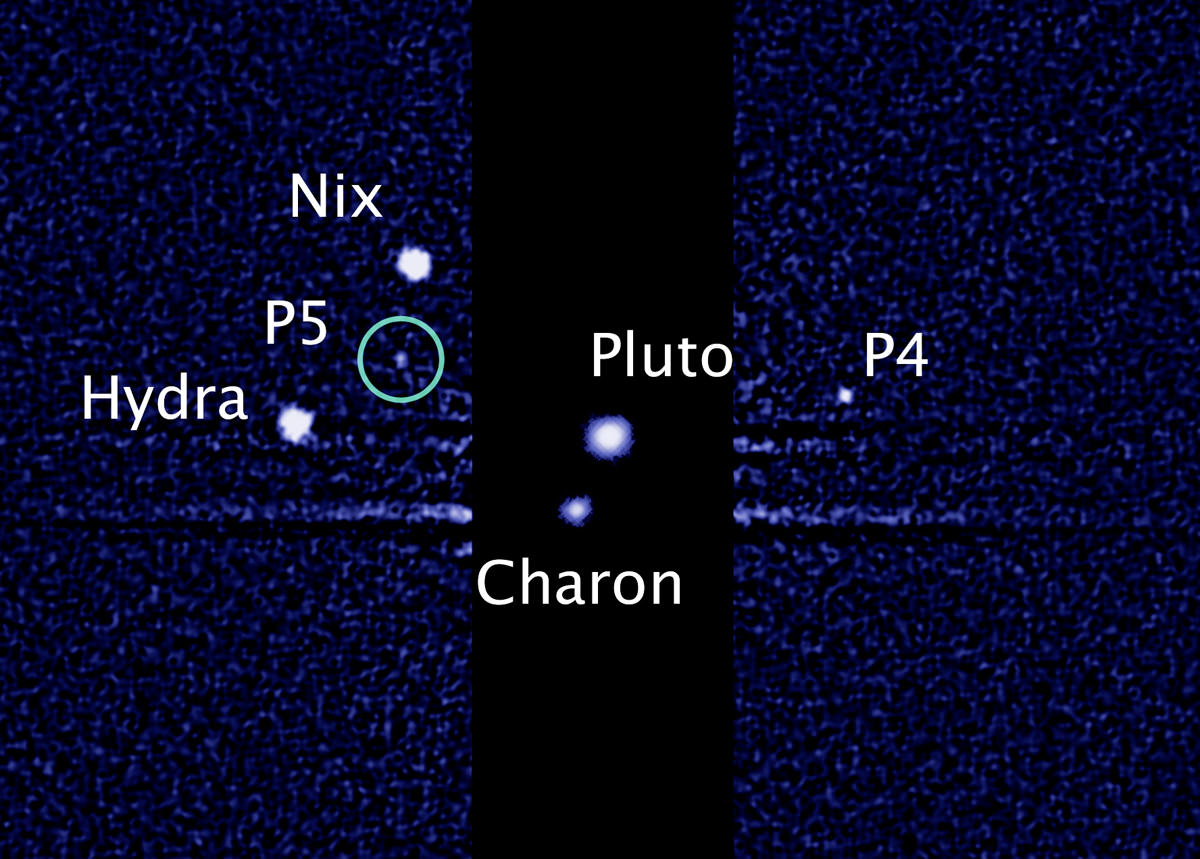

Today marks seven months since the announcement of Pluto’s fifth moon and over a year and a half since the discovery of the one before that. But both moons still have letter-and-number designations, P5 and P4, respectively… not very imaginative, to say the least, and not really fitting into the pantheon of mythologically-named worlds in our Solar System.

Today, you can help change that.

According to the New Horizons research team, after the discovery of P4 in June 2011 it was decided to wait to see if any more moons were discovered in order to choose names that fit together as a pair, while a*lso following accepted IAU naming practices. Now, seven months after the announcement of P5, we think a decision is in order… and so does the P4/P5 Discovery Team at the SETI Institute.

Today, SETI Senior Research Scientist Mark Showalter revealed a new poll site, Pluto Rocks, where visitors can place their votes on a selection of names for P4 and P5 — or even write in a suggestion of their own. In line with IAU convention these names are associated with the Greek and Roman mythology surrounding Pluto/Hades and his underworld-dwelling minions.

“In 1930, a little girl named Venetia Burney suggested that Clyde Tombaugh name his newly discovered planet ‘Pluto.’ Tombaugh liked the idea and the name stuck. I like to think that we are doing honor to Tombaugh’s legacy by now opening up the naming of Pluto’s two tiniest known moons to everyone.”

– Mark Showalter, SETI Institute

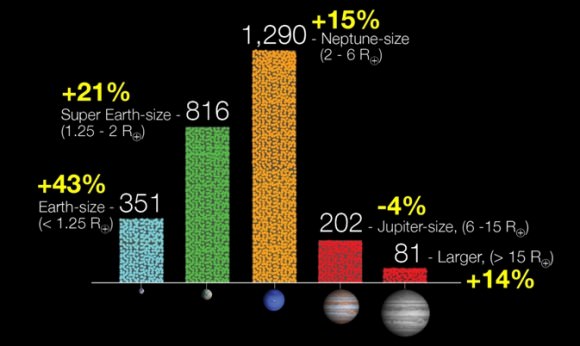

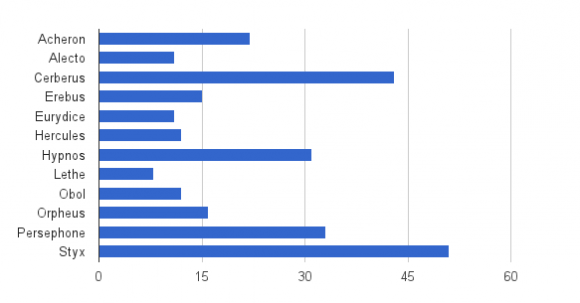

As of the time of this writing, the ongoing results look like this:

Do you like where the voting is headed? Are you hellishly opposed? Go place your vote now and make your opinion count in the naming of these two distant worlds!

(After all, New Horizons will be visiting Pluto in just under two and a half years, and she really should know how to greet the family.)

Voting ends at noon EST on Monday, February 25th, 2013.

The SETI team welcomes you to submit your vote every day, but only once per day so that voting is fair.

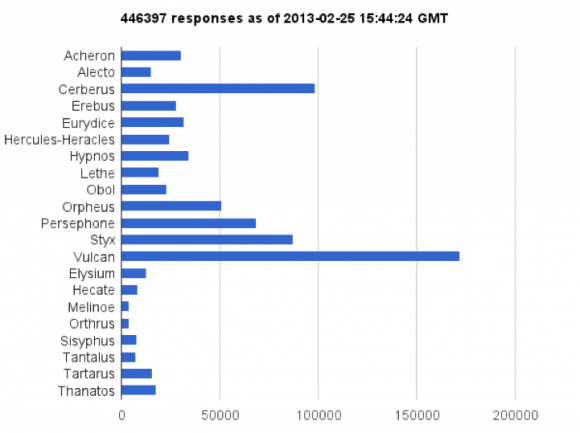

UPDATE: On Feb. 25, the final day of voting, the tally is looking like this:

Thanks in no small part to a bit of publicity on Twitter by Captain Kirk himself, Mr. William Shatner (and support by Leonard Nimoy) “Vulcan” has made the list and warped straight to the lead. Will SETI and the IAU honor such Trek fan support with an official designation? We shall soon find out…