Humans haven’t set foot on the Moon — or any other world outside of our own, for that matter — since Cernan and Schmitt departed the lunar surface on December 14, 1972. That will make 40 years on that date this coming December. And despite dreams of moon bases and lunar colonies, there hasn’t even been a controlled landing there since the Soviet Luna 24 sample return mission in 1976 (not including impacted probes.) So in light of the challenges and costs of such an endeavor, is there any real value in a return to the Moon?

Some scientists are saying yes.

Researchers from the UK, Germany and The Netherlands have submitted a paper to the journal Planetary and Space Science outlining the scientific importance of future lunar surface missions. Led by Ian A. Crawford from London’s Birkbeck College, the paper especially focuses on the value of the Moon in the study of our own planet and its formation, the development of the Earth-Moon system as well as other rocky worlds and even its potential contribution in life science and medicinal research.

Even though some research on the lunar surface may be able to be performed by robotic missions, Crawford et al. ultimately believe that “addressing them satisfactorily will require an end to the 40-year hiatus of lunar surface exploration.”

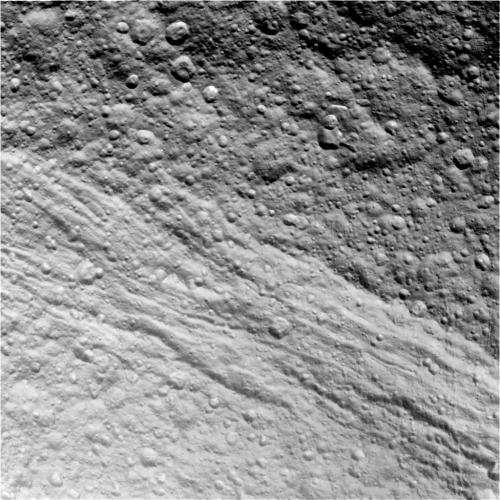

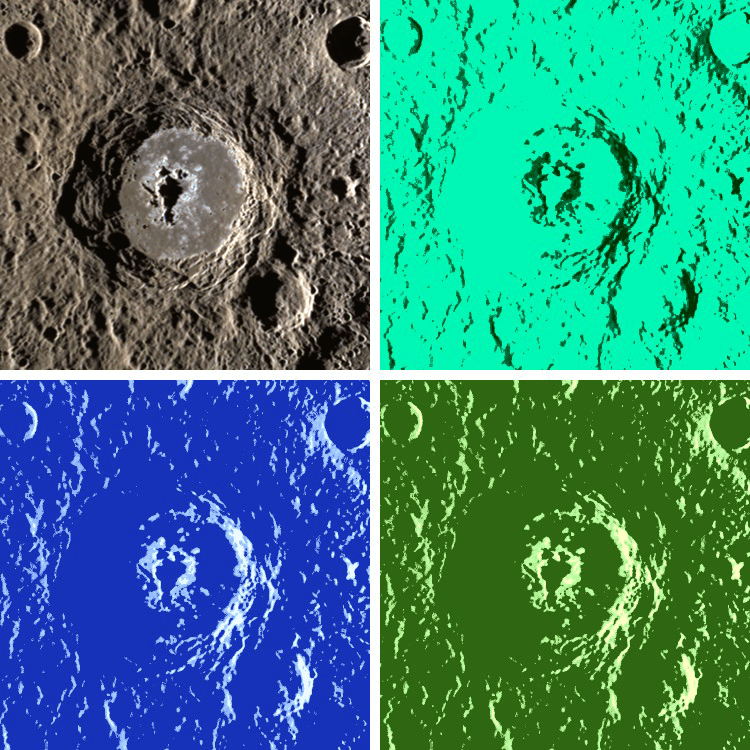

The team’s paper outlines many different areas of research that would benefit from future exploration, either manned or robotic. Surface composition, lunar volcanism, cratering history — and thus insight into a proposed period of “heavy bombardment” that seems to have affected the inner Solar System over 3.8 billion years ago — as well as the presence of water ice could be better investigated with manned missions, Crawford et al. suggest.

(Read: A New Look At Apollo Samples Supports Ancient Impact Theory)

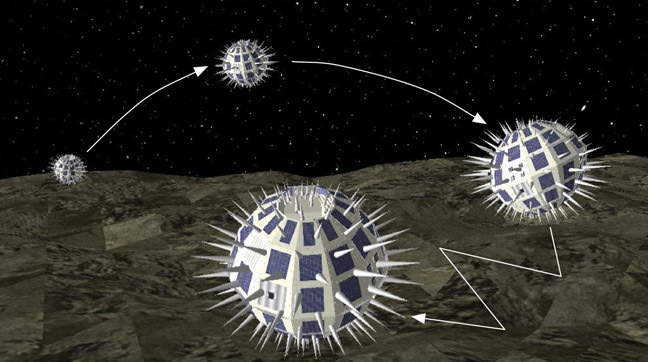

In addition, the “crashed remains of unsterilized spacecraft” on the Moon warrant study, proposes Crawford’s team. No, we’re not talking about alien spaceships — unless the aliens are us! The suggestion is that the various machinery we’ve sent to the lunar surface since the advent of the Space Age may harbor Earthly microbes that could be returned for study after decades in a lunar environment. Such research could shed new light on how life can — or can’t — survive in a space environment, as well as how long such “contaminants” might linger on another world.

Crawford’s team also argues that only manned missions could offer all-important research on the long-term effects of low-gravity environments on human physiology, as well as how to best sustain exploration crews in space. If we are to ever become a society with the ability to explore and exist beyond our own planet, such knowledge is critical.

And outside of lunar exploration itself, the Moon offers a place from which to perform deeper study of the Universe. The lunar farside, shielded as it is from radio transmissions and other interference from Earth, would be a great place for radio astronomy — especially in the low-frequency range of 10-30 MHz, which is absorbed by Earth’s ionosphere and is thus relatively unavailable to ground-based telescopes. A radio observatory on the lunar farside would have a stable platform from which to observe some of the earliest times of the Universe, between the Big Bang and the formation of the first stars.

Of course, before anything can be built on the Moon or retrieved from its surface, serious plans must be made for such missions. Fortunately, says Crawford’s team, the 2007 Global Exploration Strategy — a framework for exploration created by 13 space agencies from around the world — puts the Moon as the “nearest and first goal” for future missions, as well as Mars and asteroids. Yet with subsequent budget cuts for NASA (a key player for many exploration missions) when and how that goal will be reached still remains to be seen.

See the team’s full paper on arXiv.org here, and check out a critical review on MIT’s Technology Review.

“…this long hiatus in lunar surface exploration has been to the detriment of lunar and planetary science, and indeed of other sciences also, and that the time has come to resume the robotic and human exploration of the surface of the Moon.”

— Ian A. Crawford, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Birkbeck College, UK

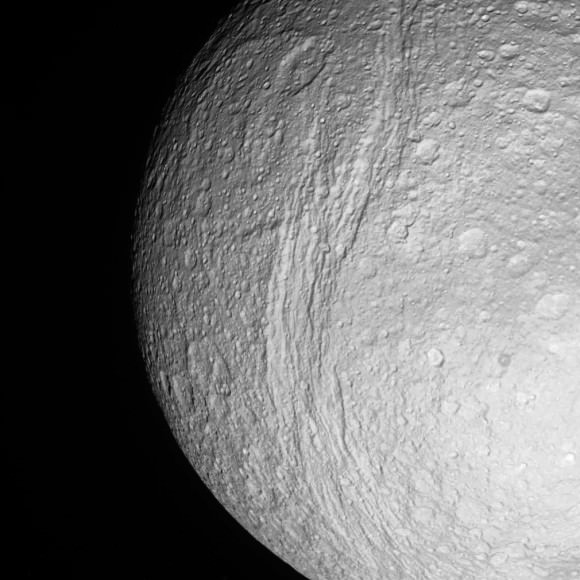

Top image from “Le Voyage Dans La Lune” by Georges Méliès, 1902. Second image: First photo of the far side of the Moon, acquired by the Soviet Luna-3 spacecraft on Oct. 7, 1959.