[/caption]

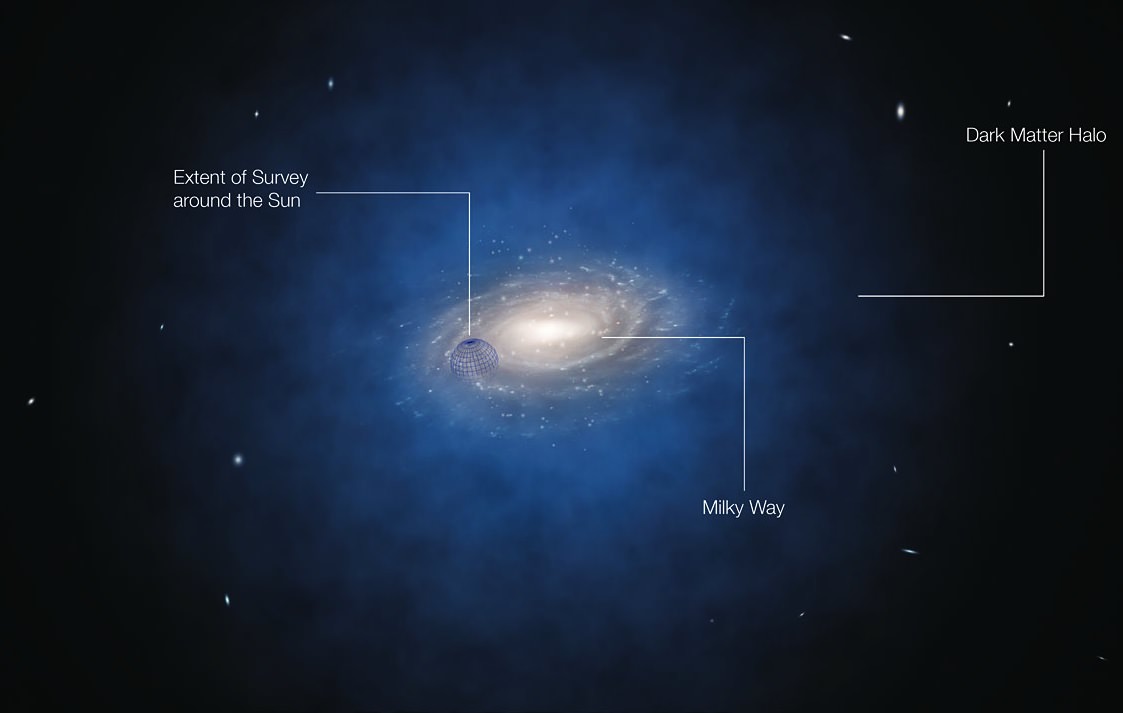

A survey of the galactic region around our solar system by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) has turned up a surprising lack of dark matter, making its alleged existence even more of a mystery.

Dark matter is an invisible substance that is suspected to exist in large quantity around galaxies, lending mass but emitting no radiation. The only evidence for it comes from its gravitational effect on the material around it… up to now, dark matter itself has not been directly detected. Regardless, it has been estimated to make up 80% of all the mass in the Universe.

A team of astronomers at ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile has mapped the region around over 400 stars near the Sun, some of which were over 13,000 light-years distant. What they found was a quantity of material that coincided with what was observable: stars, gas, and dust… but no dark matter.

“The amount of mass that we derive matches very well with what we see — stars, dust and gas — in the region around the Sun,” said team leader Christian Moni Bidin of the Universidad de Concepción in Chile. “But this leaves no room for the extra material — dark matter — that we were expecting. Our calculations show that it should have shown up very clearly in our measurements. But it was just not there!”

Based on the team’s results, the dark matter halos thought to envelop galaxies would have to have “unusual” shapes — making their actual existence highly improbable.

Still, something is causing matter and radiation in the Universe to behave in a way that belies its visible mass. If it’s not dark matter, then what is it?

“Despite the new results, the Milky Way certainly rotates much faster than the visible matter alone can account for,” Bidin said. “So, if dark matter is not present where we expected it, a new solution for the missing mass problem must be found.

“Our results contradict the currently accepted models. The mystery of dark matter has just became even more mysterious.”

Read the release on the ESO site here.