[/caption]

Was the early solar system bombarded with lots of big impacts? This is a question that has puzzled scientists for over 35 years. And it’s not just an academic one. We know from rocks on Earth that life began to evolve very early on, at least 3.8 billion years ago. If the Earth was being pummeled by large impacts at this time, this would certainly have affected the evolution of life. So, did the solar system go through what is known as the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB)? Exciting new research, using data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) may cast some doubt on the popular LHB theory.

It’s actually quite a heated debate, one that has polarized the science community for quite some time. In one camp are those that believe the solar system experienced a cataclysm of large impacts about 3.8 billion years ago. In the other camp are those that think such impacts were spread more evenly over the time of the early solar system from approximately 4.3 to 3.8 billion years ago.

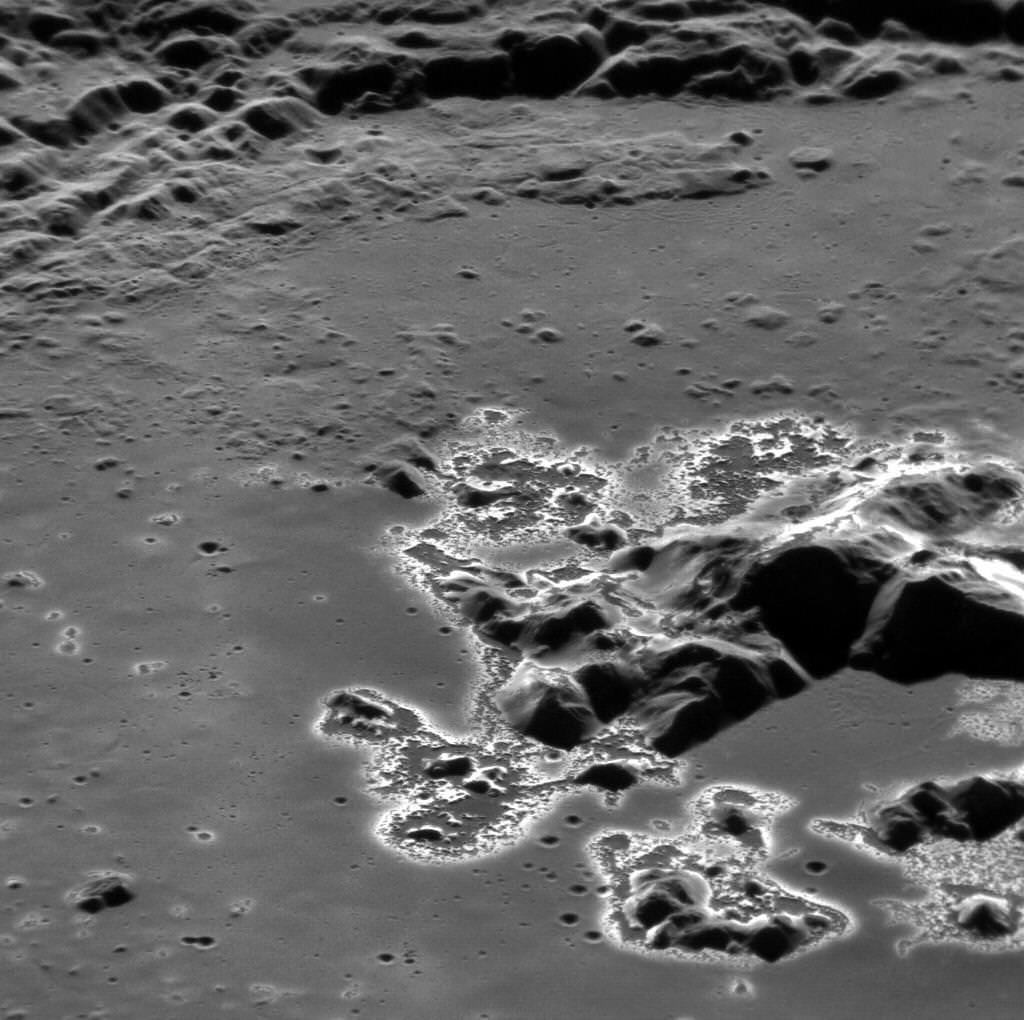

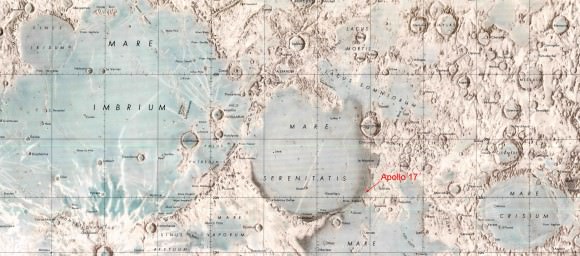

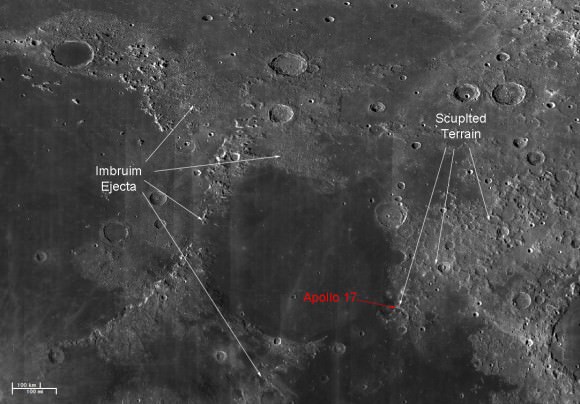

The controversy revolves around two large impact basins, which are found fairly close to each other on the Moon. The Imbrium basin is one of the youngest basins on the near side of the Moon, while the Serenetatis basin is thought to be one of the oldest. Both are flooded with volcanic basalts and are big enough to be seen from Earth with the naked eye.

What if the Apollo 17 samples didn't come from the Serenitatis basin, where the astronauts collected them, but rather from the Imbrium basin, located some 600 km away? Studies from the new Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera suggest this may be the case. If true, this means Serenitatis is much older than the Imbrium basin and a solar system-wide impact catastrophe is not needed to explain the uncannily close ages of the Imbrium and Serenitatis basins.

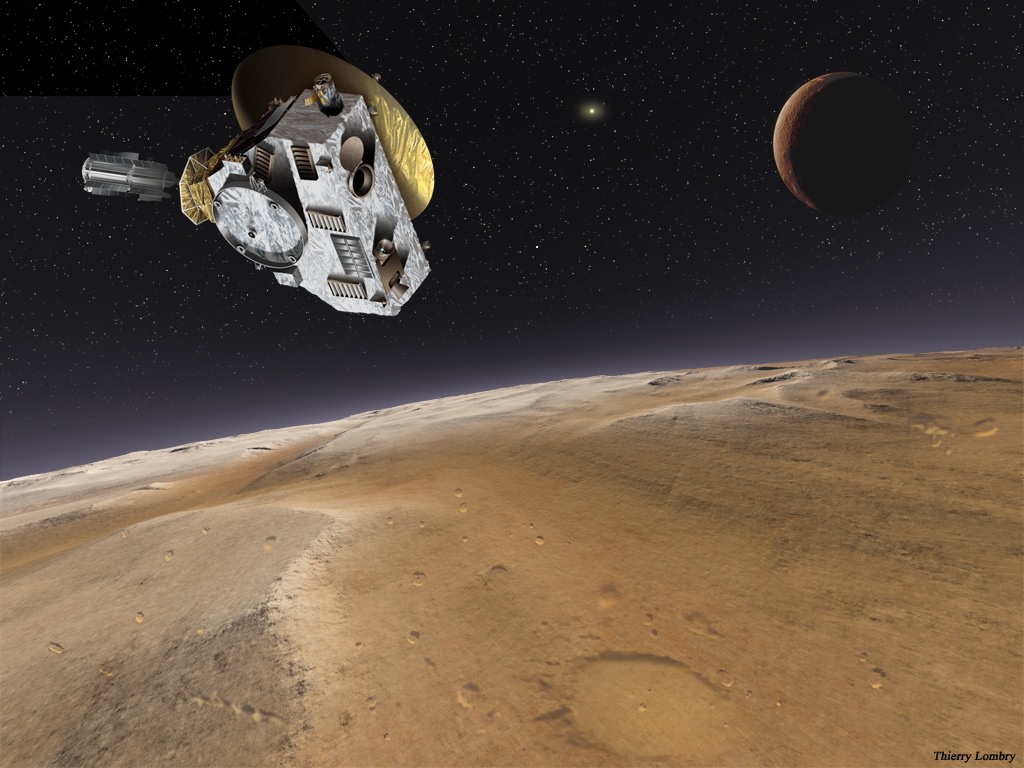

Image credit: NASA

Click on the image to download the full map and explore it in more detail.

Scientists know the relative ages of such lunar basins because of a concept called superposition. Basically, superposition states that what is on top must be younger than what is beneath. Using such relationships, scientists can determine which basins are older and which are younger.

To get an absolute age, though, scientists need actual bits of rock, so they can use radiometric dating techniques. The lunar samples returned by the Apollo program provided exactly that. But, the Apollo samples suggest that the Imbrium and Serenitatis basins are barely 50 million years apart.

Relative age dating tells us there are over 30 other basins that formed within that time frame. This means that roughly one major impact occurred every 1.5 million years! Now, 1.5 million years may sound like a long time. But consider the last large impact that happened on Earth, the Chicxulub event 65 million years ago, which is thought to have exterminated the dinosaurs. Imagine another 40 dinosaur-killing impacts occurring since then. It would be surprising if any life survived such a barrage!

This is why a team of researchers, led by Dr. Paul Spudis of the Lunar and Planetary Institute, is looking very carefully at this question. Their research is using the principle of superposition to show that several of the areas visited by the Apollo program were blanketed by material from the Imbrium impact. This could mean that many of the collected Apollo materials may be sampling the same event.

Dr. Spudis’s research focuses on the Montes Taurus area, between the Serenitatis and Crisium basins, not far from the Apollo 17 landing site. This is a region dominated by sculpted hills that have been interpreted to be ejected material from the adjacent Serenitatis basin impact. But, Dr. Spudis and his team have found that, instead, this sculpted material comes from the Imbrium basin some 600 kilometers away.

Previous data of this area, from the Lunar Orbiter IV camera, hadn’t shown this because a fog on the camera lens made the details difficult to see (this fog problem was eventually resolved, and Lunar Orbiter IV provided a lot of useful data on other parts of the Moon).The new LROC data, however, shows that the sculpted terrain seen at Apollo 17 is very widespread, extending far beyond the Montes Taurus region. Furthermore, the grooves and lineated features of this terrain point to the Imbrium basin, not the Serenitatis basin, and line up with similar features in the Alpes and Fra Mauro Formations, which are known to be ejecta from the Imbrium impact. In the north of Serenitatis, these Imbrium formations even seem to transform into the Montes Taurus, confirming that the sculpted hills do, in fact, originate from the Imbrium impact.

Image credit: NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

Click on the image to explore the LROC data in greater detail.

If the sculpted hills are Imbruim ejecta, then it is possible that Apollo 17 sampled Imbrium and not Serenitatis materials. That casts suspicion on the very close radiometric ages of these two basins. Perhaps these ages are so close because we effectively measured the same material. In that case, the age of Serenitatis could be much older than the 3.87 billion years the Apollo 17 samples suggest. If true, this would mean that there was no Late Heavy Bombardment at the time life was forming on the early Earth, leaving life to evolve with relatively few impact-related interruptions.

Source:

Spudis et al., 2011, Journal of Geophysical Research, V116, E00H03