[/caption]

With the Moon as the most prominent object in the night sky and a major source of an invisible pull that creates ocean tides, many ancient cultures thought it could also affect our health or state of mind – the word “lunacy” has its origin in this belief. Now, a powerful combination of spacecraft and computer simulations is revealing that the moon does indeed have a far-reaching, invisible influence – not on us, but on the Sun, or more specifically, the solar wind.

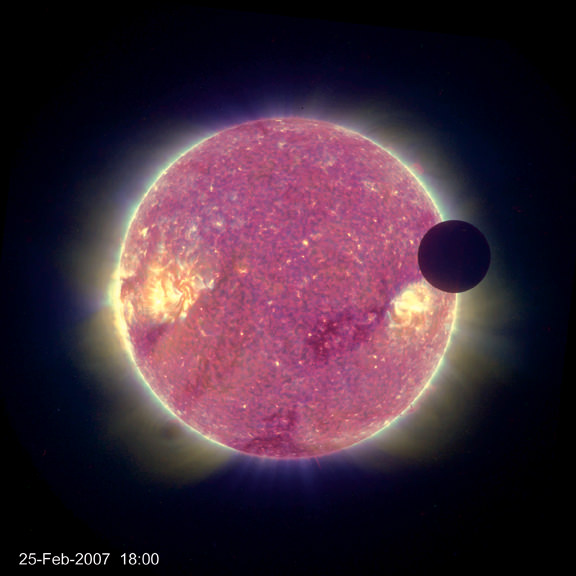

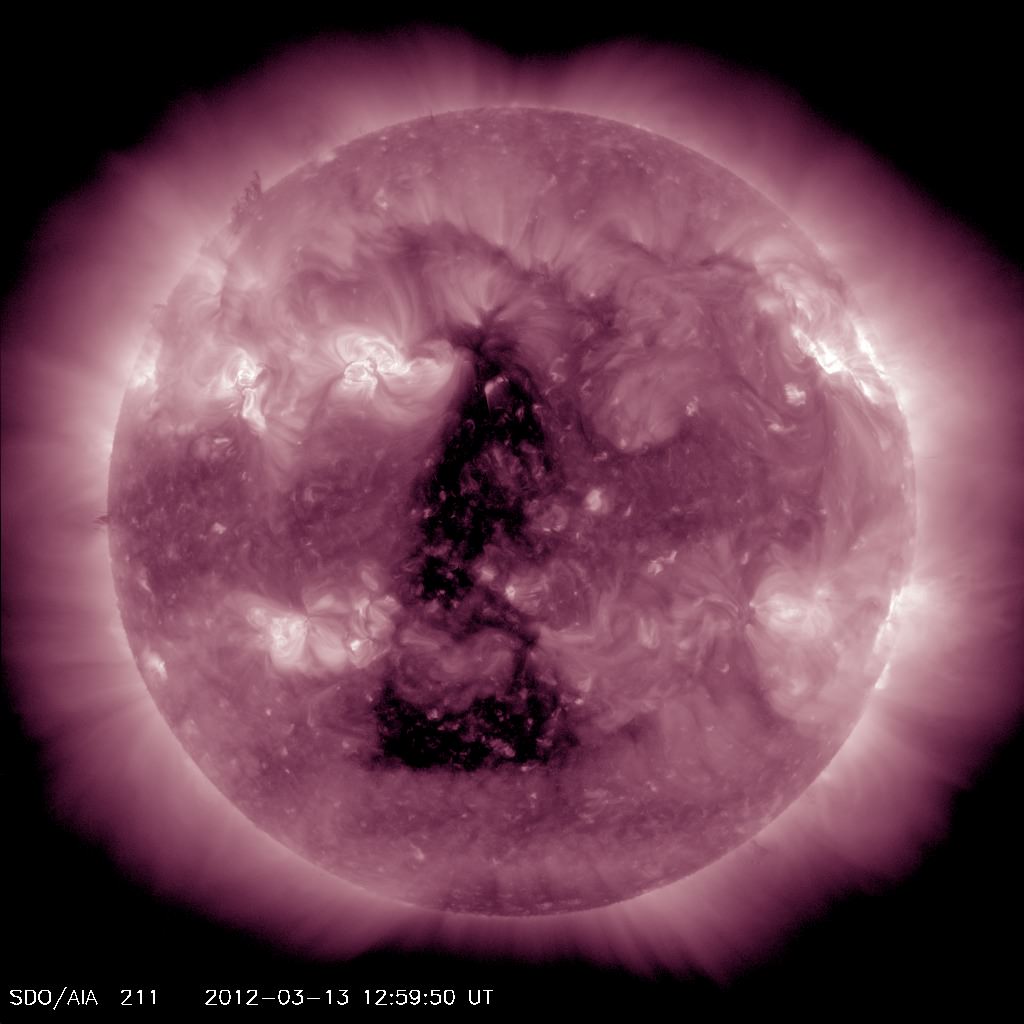

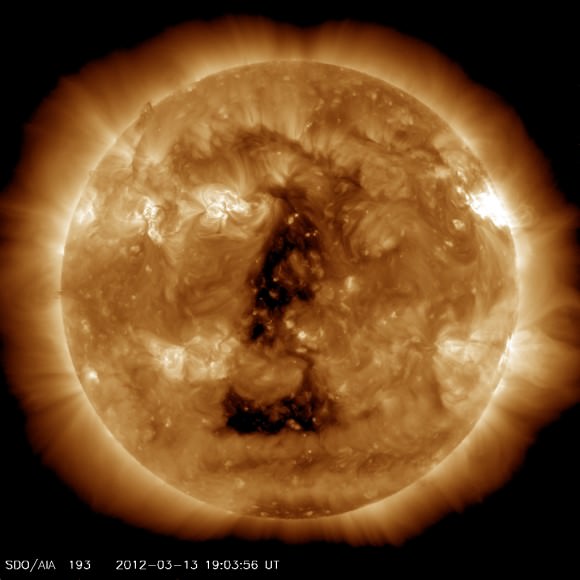

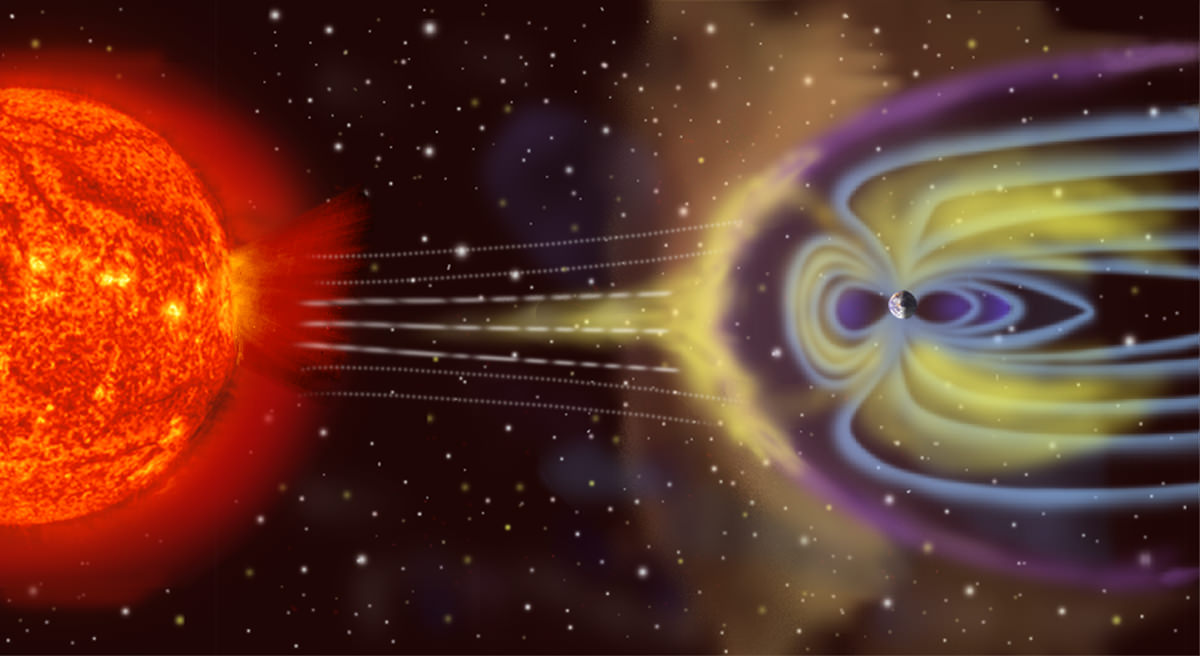

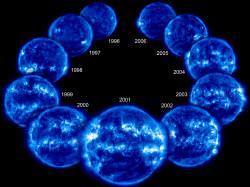

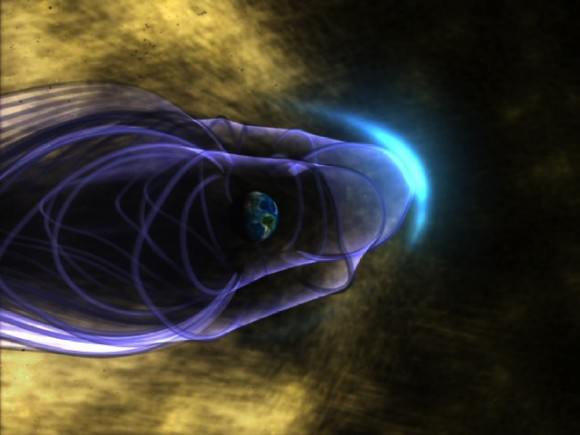

The solar wind is a thin stream of electrically conducting gas called plasma that’s constantly blown off the surface of the Sun in all directions at around a million miles per hour. When a particularly fast, dense or turbulent solar wind strikes Earth’s magnetic field, it can generate magnetic and radiation storms that are capable of disrupting satellites, power grids, and communication systems. The magnetic “bubble” surrounding Earth also pushes back on the solar wind, creating a bow shock tens of thousands of miles across over the day side of Earth where the solar wind slams into the magnetic field and abruptly slows from supersonic to subsonic speed.

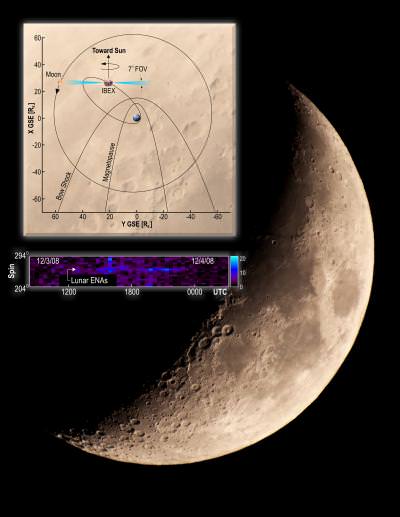

Unlike Earth, the Moon is not surrounded by a global magnetic field. “It was thought that the solar wind crashes into the lunar surface without any warning or ‘push back’ on the solar wind,” says Dr. Andrew Poppe of the University of California, Berkeley. Recently, however, an international fleet of lunar-orbiting spacecraft has detected signs of the Moon’s presence “upstream” in the solar wind. “We’ve seen electron beams and ion fountains over the Moon’s day side,” says Dr. Jasper Halekas, also of the University of California, Berkeley.

These phenomena have been seen as far as 10,000 kilometers (6,214 miles) above the Moon and generate a kind of turbulence in the solar wind ahead of the Moon, causing subtle changes in the solar wind’s direction and density. The electron beams were first seen by NASA’s Lunar Prospector mission, while the Japanese Kaguya mission, the Chinese Chang’e mission, and the Indian Chandrayaan mission all saw ion plumes at low altitudes. NASA’s ARTEMIS mission has now also seen both the electron beams and the ion plumes, plus newly identified electromagnetic and electrostatic waves in the plasma ahead of the Moon, at much greater distances from the moon. “With ARTEMIS, we can see the plasma ring and wiggle a bit, surprisingly far away from the Moon,” says Halekas. ARTEMIS stands for “Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence and Electrodynamics of the Moon’s Interaction with the Sun”.

“An upstream turbulent region called the ‘foreshock’ has long been known to exist ahead of the Earth’s bow shock, but the discovery of a similar turbulent layer at the moon is a surprise,” said Dr. William Farrell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. Farrell is lead of the NASA Lunar Science Institute’s Dynamic Response of the Environment At the Moon (DREAM) lunar science center, which contributed to the research.

Computer simulations help explain these observations by showing that a complex electric field near the lunar surface is generated by sunlight and the flow of the solar wind. The simulation reveals this electric field can generate electron beams by accelerating electrons blasted from surface material by solar ultraviolet light. Also, related simulations show that when ions in the solar wind collide with ancient, “fossil” magnetic fields in certain areas on the lunar surface, they are reflected back into space in a diffuse, fountain-shaped pattern. These ions are mostly the positively charged ions (protons) of hydrogen atoms, the most common element in the solar wind.

“It’s remarkable that electric and magnetic fields within just a few meters (yards) of the lunar surface can cause the turbulence we see thousands of kilometers away,” says Poppe. When exposed to solar winds, other moons and asteroids in the solar system should have this turbulent layer over their day sides as well, according to the team.

“Discovering more about this layer will enhance our understanding of the Moon and potentially other bodies because it allows information about conditions very near the surface to propagate to great distances, so a spacecraft will gain the ability to virtually explore close to these objects when it’s actually far away,” said Halekas.

The research is described in a series of six papers recently published by Poppe, Halekas, and their colleagues at NASA Goddard, U.C. Berkeley, U.C. Los Angeles, and the University of Colorado at Boulder in Geophysical Research Letters and the Journal of Geophysical Research. The research was funded by NASA’s Lunar Science Institute, which is managed at NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif., and oversees the DREAM lunar science center.