[/caption]

The Russia space agency has set dates for resuming flights with the Progress and Soyuz spacecraft. After determining the cause of the failure and crash of a Soyuz-U rocket carrying a Progress cargo ship bound for the International Space Station last month, Roscomos said they will be resuming flights soon, and the next Soyuz-U Progress launch will be on Sunday, October 30, 2011. “It is planned to launch Progress cargo spaceships on October 30, 2011, and on January 26, 2012. Manned Soyuz-FG spaceships will be launched on November 12 and December 20, 2011,” the agency said on their website.

The commission that investigated the crash has “approved the schedule of preparation and launch of spacecraft … The schedule is based on the analysis of willingness to third propulsion launch vehicle and taking into account the implementation of all recommendations developed by the commission.”

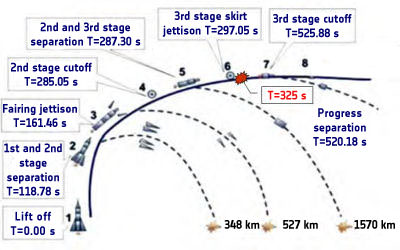

The commission said the crash was caused by a malfunction in the rocket’s third stage engine gas generator, which they determined was the result of a manufacturing flaw, which was “accidental.”

Roscosmos said they are also consulting with NASA to “refine the work plans of the upcoming missions to the International Space Station.” NASA has not made a statement yet on the plans laid out today by the Russian space agency.

If all goes well with the October 30 Progress launch, it will be interesting to see if all parties agree to allow NASA Flight Engineer Dan Burbank, Soyuz Commander Anton Shkaplerov and Russian Flight Engineer Anatoly Ivanishin to climb on board a Soyuz flight less than two weeks later.

Meanwhile, two Soyuz ST space vehicles carrying satellites that are being prepared for launch from the Kourou spaceport in French Guiana will have the third stages of their rockets changed out, according to a spokesman from the Arianespace launch service corporation and the Russian news service Itar-Tass.

The third stages of two rockets will be returned to Russia, and new stages will be delivered to Kourou.

A spokesman for the Russian Space Mission Control said the resumption of manned and cargo launches means the ISS won’t need to be evacuated.

“This means that the ISS will constantly operate in piloted mode, with astronauts onboard,” spokesman Valery Lyndin told AFP. “Crews will be changed as originally planned, only the schedule will be somewhat pushed back.”

The first three of the current crew of six on board the station are schedule to return to Earth on Friday. NASA TV will broadcast the return on September 15, as Expedition 28 Soyuz Commander Alexander Samokutyaev, NASA Flight Engineer Ron Garan and off-going station Commander Andrey Borisenko will undock from the station’s Poisk module to return to Earth in their Soyuz TMA-21 spacecraft.

They are set to land on the southern region steppe of Kazakhstan near the town of Dzhezkazgan at 11:01 p.m. CDT on Sept. 15 (10:01 a.m. local time, Sept. 16). Their return was delayed a week due to the Aug. 24 Progress 44 crash.

Expedition 29 station Commander Mike Fossum of NASA, Russian Flight Engineer Sergei Volkov and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency Flight Engineer Satoshi Furukawa will remain aboard the complex to conduct research until their planned return to Earth in mid-November.

The schedule to launch three new Expedition 29 crew members, is under review as NASA and its international partners assess the readiness to resume Soyuz launches.

Sources: Roscosmos, PhysOrg, Ciudad Futura (link for lead image)