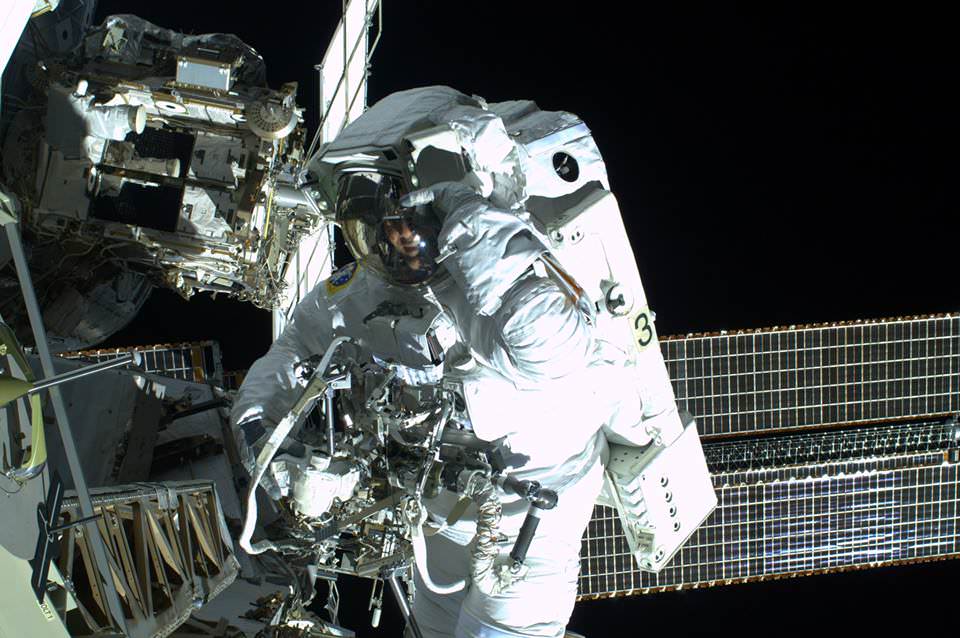

On July 16, Expedition 36 astronauts Chris Cassidy and Luca Parmitano had to cut a planned 7-hour spacewalk short after only an hour and a half due to a malfunction in Parmitano’s space suit, leaking water into his helmet and eventually cutting off his vision, hearing, and communications. Fortunately the Italian test pilot was able to safely return inside the ISS, but for several minutes he was faced with a pretty frightening situation: stuck outside Space Station with his head in a fishbowl that was rapidly filling with water.

On August 20, he shared his personal account of the event on his ESA blog.

“The only idea I can think of is to open the safety valve by my left ear: if I create controlled depressurisation, I should manage to let out some of the water, at least until it freezes through sublimation, which would stop the flow. But making a ‘hole’ in my spacesuit really would be a last resort…”

Parmitano’s description of his suit mishap begins as I’m sure all spacewalks do: with a sense of energy and enthusiasm for a job about to be performed in a challenging yet exotic and undeniably privileged location.

“My eyes are closed as I listen to Chris counting down the atmospheric pressure inside the airlock – it’s close to zero now. But I’m not tired – quite the reverse! I feel fully charged, as if electricity and not blood were running through my veins. I just want to make sure I experience and remember everything. I’m mentally preparing myself to open the door because I will be the first to exit the Station this time round. Maybe it’s just as well that it’s night time: at least there won’t be anything to distract me.”

But even though the EVA initially progressed as planned — ahead of schedule, in fact — it soon became obvious to Parmitano that something was amiss with his suit.

“The unexpected sensation of water at the back of my neck surprises me – and I’m in a place where I’d rather not be surprised. I move my head from side to side, confirming my first impression, and with superhuman effort I force myself to inform Houston of what I can feel, knowing that it could signal the end of this EVA.”

It didn’t take long before an uncomfortable situation escalated into something potentially very dangerous.

“As I move back along my route towards the airlock, I become more and more certain that the water is increasing. I feel it covering the sponge on my earphones and I wonder whether I’ll lose audio contact. The water has also almost completely covered the front of my visor, sticking to it and obscuring my vision. I realise that to get over one of the antennae on my route I will have to move my body into a vertical position, also in order for my safety cable to rewind normally. At that moment, as I turn ‘upside-down’, two things happen: the Sun sets, and my ability to see – already compromised by the water – completely vanishes, making my eyes useless; but worse than that, the water covers my nose – a really awful sensation that I make worse by my vain attempts to move the water by shaking my head. By now, the upper part of the helmet is full of water and I can’t even be sure that the next time I breathe I will fill my lungs with air and not liquid. To make matters worse, I realise that I can’t even understand which direction I should head in to get back to the airlock. I can’t see more than a few centimetres in front of me, not even enough to make out the handles we use to move around the Station.”

After contemplating opening a hole in his helmet to let out some of the water — a “last resort,” indeed — Parmitano managed to get back inside the airlock with help from Cassidy. But he still had to deal with the process of repressurization, which itself takes a few minutes.

Read more: Space Water Leak Prompts NASA Mishap Investigation

“I try to move as little as possible to avoid moving the water inside my helmet. I keep giving information on my health, saying that I’m ok and that repressurization can continue. Now that we are repressurizing, I know that if the water does overwhelm me I can always open the helmet. I’ll probably lose consciousness, but in any case that would be better than drowning inside the helmet.”

Now, a month after the mishap, Parmitano reflects on the nature of the event and of space travel in general.

“Space is a harsh, inhospitable frontier and we are explorers, not colonisers. The skills of our engineers and the technology surrounding us make things appear simple when they are not, and perhaps we forget this sometimes.”

“Better not to forget,” he advises.

Read Luca’s full blog post on the ESA site here.

ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano is the first of ESA’s new generation of astronauts to fly into space. Luca will serve as flight engineer on the Station for Expeditions 36 and 37. He qualified as a European astronaut and was proposed by Italy’s ASI space agency for this mission.