Two possiblities exist: either the Universe is finite and has a size, or it’s infinite and goes on forever. Both possibilities have mind-bending implications.

In another episode of Guide to Space, we talked: “how big is our Universe”. Then I said it all depends on whether the Universe is finite or infinite. I mumbled, did some hand waving, glossed over the mind-bending implications of both possibilities and moved on to whatever snarky sci-cult reference was next because I’m a bad host. I acted like nothing happened and immediately got off the elevator.

So, in the spirit of he who smelled it, dealt it. I’m back to shed my cone of shame and talk big universe. And if the Universe is finite, well, it’s finite. You could measure its size with a really long ruler. You could also follow up statements like that with all kinds of crass shenanigans. Sure, it might wrap back on itself in a mindbending shape, like a of monster donut or nerdecahedron, but if our Universe is infinite, all bets are off. It just goes on forever and ever and ever in all directions. And my brain has already begun to melt in anticipation of discussing the implications of an infinite Universe.

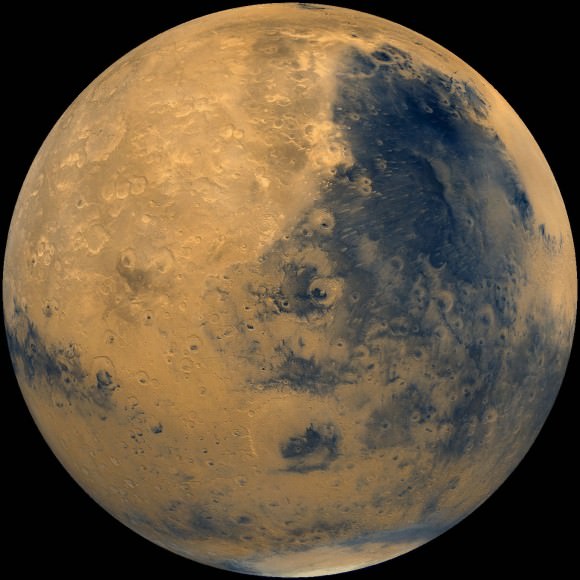

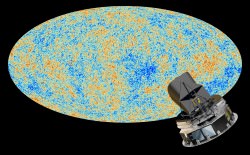

Haven’t astronomers tried to figure this out? Of course they have, you fragile mortal meat man/woman! They’ve obsessed over it, and ordered up some of the most powerful sensitive space satellites ever built to answer this question.Astronomers have looked deep at the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang. So, how would you test this idea just by watching the sky?

Here’s how smart they are. They’ve searched for evidence that features on one side of the sky are connected to features on the other side of the sky, sort of like how the sides of a Risk map connect to each other, or there’s wraparound on the PacMan board. And so far, there’s no evidence they’re connected.

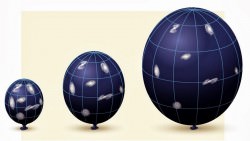

In our hu-man words, this means 13.8 billion light-years in all directions, the Universe doesn’t repeat. Light has been travelling towards us for 13.8 billion years this way, and 13.8 billion years that way, and 13.8 billion years that way; and that’s just when the light left those regions. The expansion of the Universe has carried them from 47.5 billion light years away. Based on this, our Universe is 93 billion light-years across. That’s an “at least” figure. It could be 100 billion light-years, or it could be a trillion light-years. We don’t know. Possibly, we can’t know. And it just might be infinite.

If the Universe is truly infinite, well then we get a very interesting outcome; something that I guarantee will break your brain for the entire day. After moments like this, I prefer to douse it in some XKCD, Oatmeal and maybe some candy crush.

Consider this. In a cubic meter (or yard) of space. Alright, in a box of space about yay big (show with hands), there’s a finite number of particles that can possibly exist in that region, and those particles can have a finite number of configurations considering their spin, charge, position, velocity and so on.

Tony Padilla from Numberphile has estimated that number to be 10 to the power of 10 to the power of 70. That’s a number so big that you can’t actually write it out with all the pencils in the Universe. Assuming of course, that other lifeforms haven’t discovered infinite pencil technology, or there’s a pocket dimension containing only pencils. Actually, it’s probably still not enough pencils.

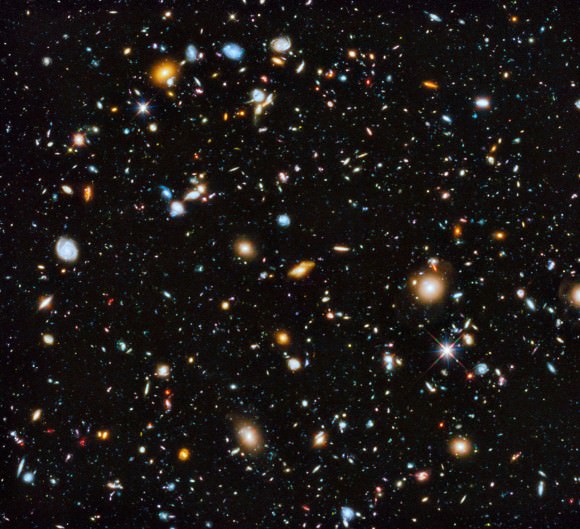

There are only 10 ^ 80 particles in the observable Universe, so that’s much less than the possible configurations of matter in a cubic meter. If the Universe is truly infinite, if you travel outwards from Earth, eventually you will reach a place where there’s a duplicate cubic meter of space. The further you go, the more duplicates you’ll find.

Ooh, big deal, you think. One hydrogen pile looks the same as the next to me. Except, you hydromattecist, you’ll pass through places where the configuration of particles will begin to appear familiar, and if you proceed long enough you’ll find larger and larger identical regions of space, and eventually you’ll find an identical you. And finding a copy of yourself is just the start of the bananas crazy things you can do in an infinite Universe.

In fact, hopefully you’ll absorb the powers of an immortal version of you, because if you keep going you’ll find an infinite number of yous. You’ll eventually find entire duplicate observable universes with more yous also collecting other yous. And at least one of them is going to have a beard.

So, what’s out there? Possibly an infinite number of duplicate observable universes. We don’t even need multiverses to find them. These are duplicate universes inside of our own infinite universe. That’s what you can get when you can travel in one direction and never, ever stop.

Whether the Universe is finite or infinite is an important question, and either outcome is mindblenderingly fun. So far, astronomers have no idea what the answer is, but they’re working towards it and maybe someday they’ll be able to tell us.

So what do you think? Do we live in a finite or infinite universe? Tell us in the comments below.