When you look up and see the Milky Way, you’re gazing into the heart of our home galaxy. What, exactly, are we looking at?

Anyone who’s ever been in truly dark skies has seen the Milky Way. The bright band across the sky is unmistakable. It’s a view of our home galaxy from within.

As you stare out into the skies and see that splash of stars, have you ever wondered, what are you looking at? Which parts are towards the inside of the galaxy and which parts are looking out? Where’s that supermassive black hole you’ve heard so much about?

In order to see the Milky Way at all, you need seriously dark skies, away from the light polluted city. As the skies darken, the Milky Way will appear as a hazy fog across the sky.

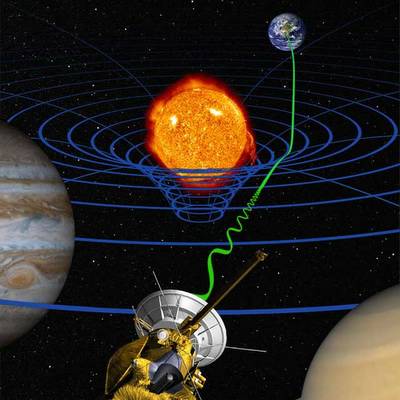

Imagine it as this vast disk of stars, with the Sun embedded right in it, about 27,000 light-years from the core. We’re seeing the galaxy edge on, from the inside, and so we see the galactic disk as a band that forms a complete circle around the sky.

Which parts you can see depend on your location on Earth and the time of year, but you can always see some part of the disk.

The galactic core of the Milky Way is located in the constellation Sagittarius, which is located to the South of me in Canada, and only really visible during the Summer. In really faint skies, the Milky Way is clearly thicker and brighter in that region.

Want to know the exact point of the galactic core? It’s right… there.

During the Winter, we’re looking away from the galactic core to the outer regions of the galaxy. It still has the same band of stars, but it’s thinner and without the darker clouds of dust that obscure our view to the galactic core.

How do astronomers even know that we’re in a spiral galaxy anyway?

There are two major types of galaxies, spiral galaxies and elliptical galaxies.

Elliptical galaxies are made up of so many galactic collisions, they’re nothing more than vast balls of trillions of stars, with no structure. Because we can see a distinct band in the sky, we know we’re in some kind of spiral.

Astronomers map the arms by looking at the distribution of gas, which pulls together in star forming spiral arms. They can tell how far the major arms are from the Sun and in which direction.

The trick is that half the Milky Way is obscured by gas and dust. So we don’t really know what structures are on the other side of the galactic disk. With more powerful infrared telescopes, we’ll eventually be able to see though the gas and dust and map out all the spiral arms.

If you’ve never seen the Milky Way with your own eyes, you need to. Get far enough away from city lights to truly see the galaxy you live in.

The best resource is “The Dark Sky Finder”, we’ll put a link in the show notes.

Have you ever seen the Milky Way? If not, why not? Let’s hear a story of a time you finally saw it.

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!