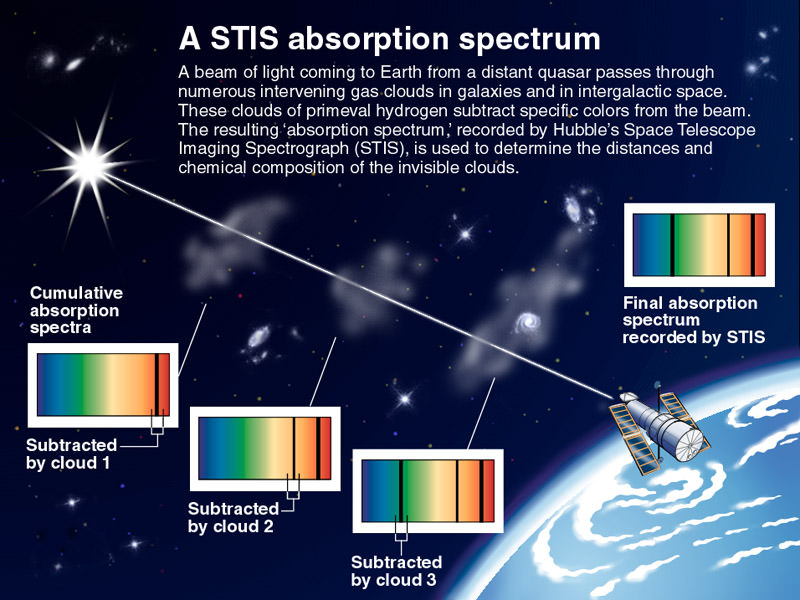

One of the greatest potentials of transiting exoplanets is the ability to monitor the spectra and examine the composition of the planet’s atmosphere. This has been done already for HD 18733b and HD 209458b. In a new article by a team of astronomers at Keele University in the UK, absorption spectroscopy has been applied to the unusual exoplanet WASP-17b, which is known to orbit retrograde.

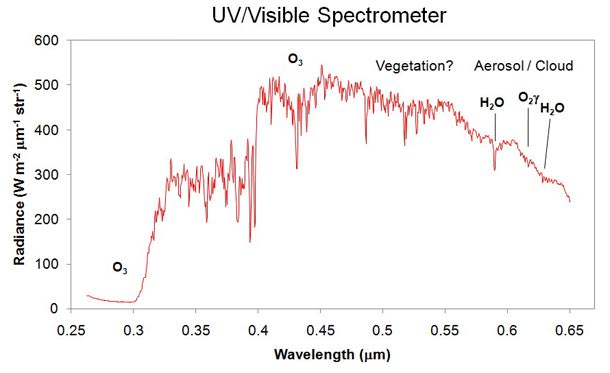

Not only does the spectra tell astronomers the atmospheric composition, but can also give an understanding of the the composition, but can also be indicative of how the atmosphere absorbs the light from the star and how heat is transferred around the planet. Additionally, since the atmosphere will absorb differently at different wavelengths, this gives differences in the timing of the eclipse and can be used to probe the radius of the planet more tightly as well as potentially examining the layering of the atmosphere.

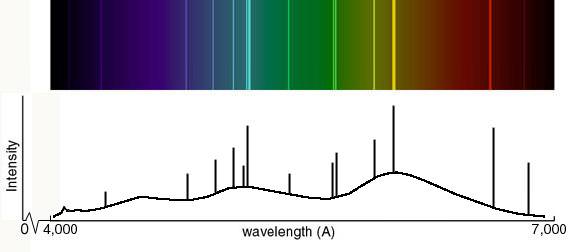

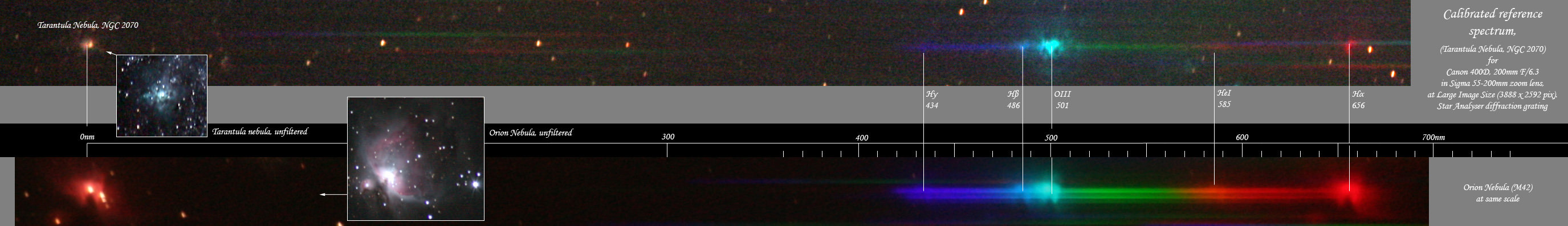

For their investigation, the team concentrated on the sodium doublet lines at 5889.95 and 5895.92 Å. Observations were taken by the Very Large Telescope in Chile to observe 8 transits of the planet in June of 2009. The planet itself has a short orbit of 3.74 days.

Applying these spectroscopic techniques to WASP-17b, the team discovered the presence of sodium in the atmosphere. Yet the absorption wasn’t as strong as expected based on models using formation mechanisms from a nebula with solar composition and forming a planet with a cloudless atmosphere. Instead, the team describes 17b’s atmosphere as “sodium-depleted” similar to HD 209458b.

An additional observation was that the depth of seeing dropped off when using certain filters with different bandwidths (ranges of allowed wavelengths). The team noted that at bandwidths greater than 3.0 Å, the amount of sodium absorption seen nearly disappeared. Since this property is related to how much atmosphere the light travels through, this allowed the team to speculate that this may be indicative of clouds in the upper layers of the atmosphere.

Lastly, the team speculated as to the reason on the lack of sodium in the atmosphere. They proposed that energy from the star ionizes sodium on the day side. The motion of the atmosphere carrying it to the night side would then allow it to condense and be removed from the atmosphere. Since giant exoplanets in such tight orbits would likely be tidally locked, the sodium would have little chance to return to the day side and be brought back into the atmosphere.

While the examination of extrasolar atmospheres is undoubtedly new and will certainly be revised as the number of explored atmospheres increases, these pioneering studies are among the first that can allow astronomers directly test predictions of planetary atmospheres which, until recently have been solely based on observations of our own solar system. More generally, this will allow us to develop a fuller understanding of how planets evolve.