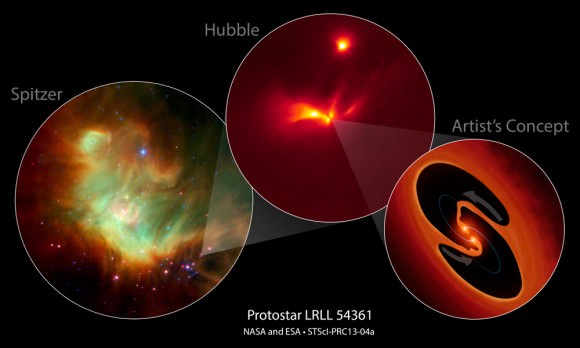

It seems that every few months or so comes a new discovery of a new “most distant galaxy ever found.” It’s not really a surprise that new benchmarks are reached with such an amazing frequency as our telescopes get better and astronomers refine their techniques for observing faraway and ancient objects. This latest “most distant” is pretty interesting in that it was found by combining observations from two space telescopes – Hubble and Spitzer – as well as using massive galaxy clusters as gravitational lenses to magnify the distant galaxy behind them. It’s also extremely small and may not even be a fully developed galaxy at the time we are seeing it.

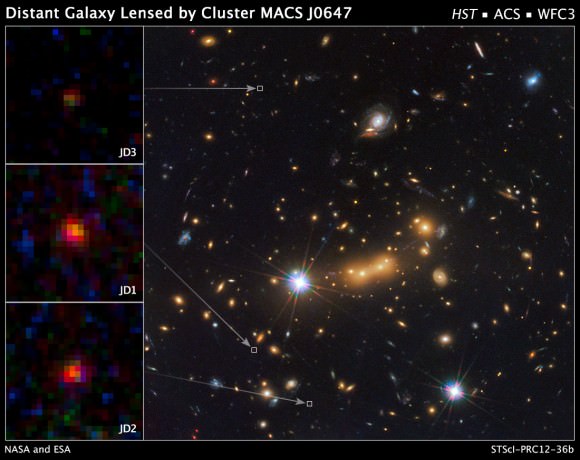

While this galaxy, named MACS0647-JD, appears as a diminutive blob in the new images, astronomers say it offers a peek back into a time when the universe was just 3 percent of its present age of 13.7 billion years. This newly discovered galaxy was observed 420 million years after the Big Bang, and its light has traveled 13.3 billion years to reach Earth.

“This object may be one of many building blocks of a galaxy,” said Dan Coe of the Space Telescope Science Institute, lead author of a new paper on the observations. “Over the next 13 billion years, it may have dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of merging events with other galaxies and galaxy fragments.”

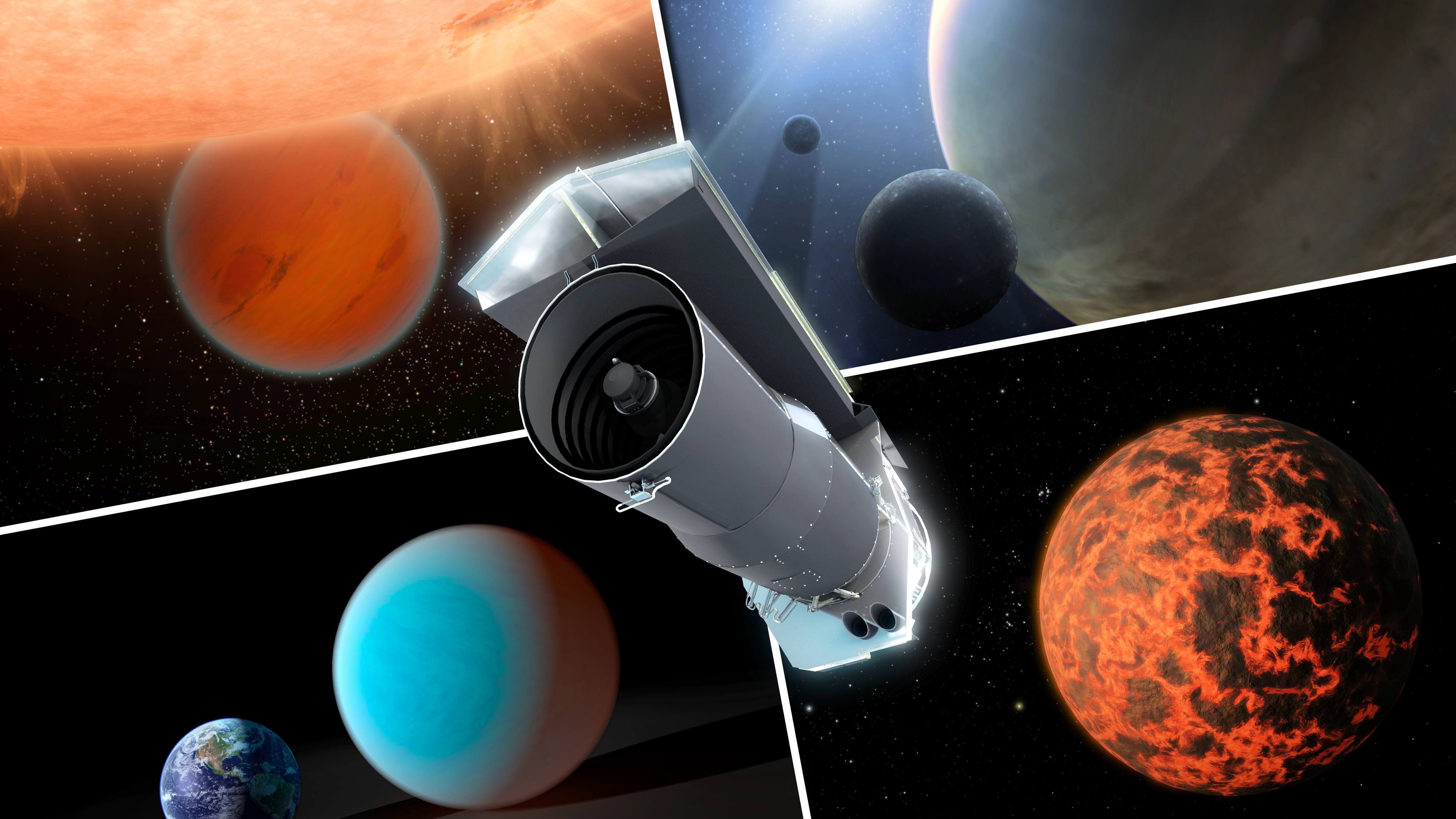

The discovery comes from the Cluster Lensing And Supernova Survey with Hubble (CLASH), a program that combines the power of space telescopes with the natural zoom of gravitational lensing to reveal distant galaxies in the early Universe. Observations with Spitzer’s infrared eyes allowed for confirmation of this object.

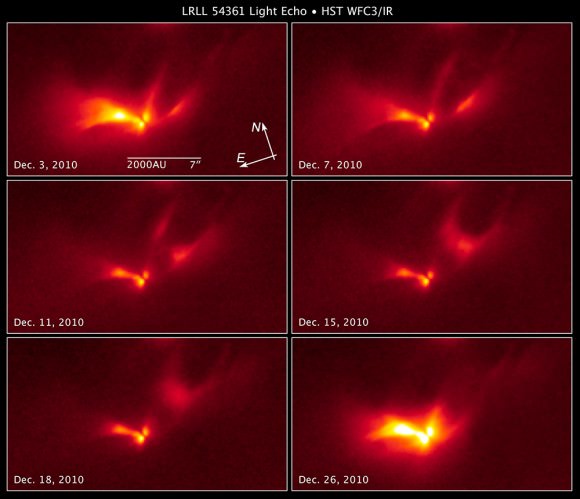

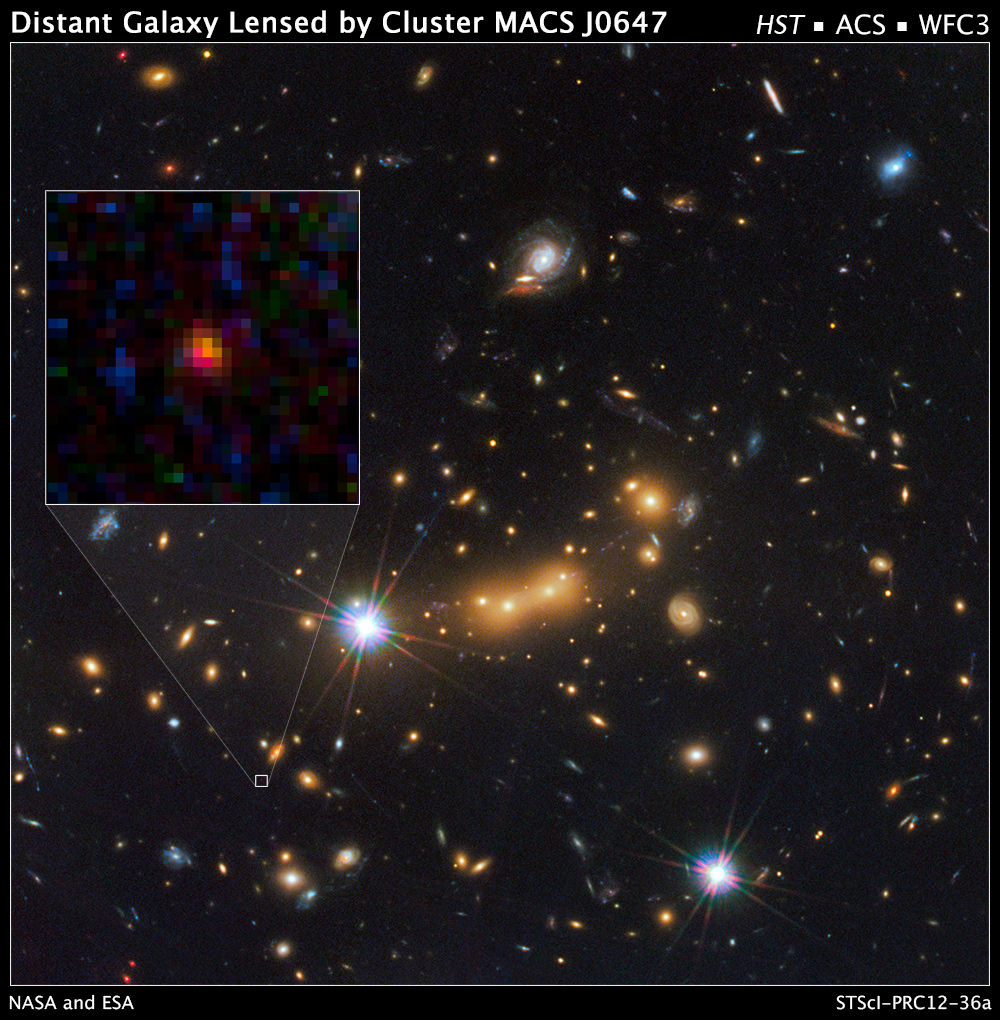

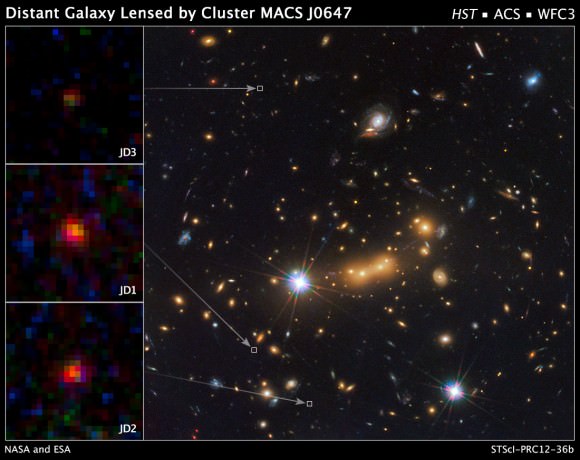

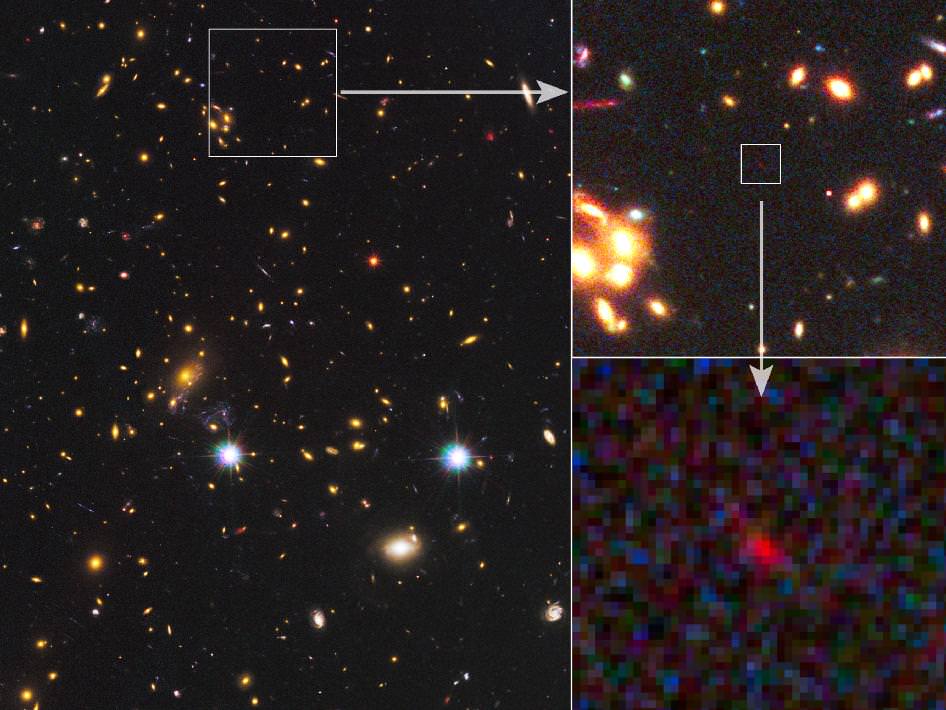

The light from MACS0647-JD was magnified by a massive galaxy cluster named MACS J0647+7015, and without the cluster’s magnification powers, astronomers would not have seen the remote galaxy. Because of gravitational lensing, the CLASH research team was able to observe three magnified images of MACS0647-JD with the Hubble telescope. The cluster’s gravity boosted the light from the faraway galaxy, making the images appear about eight, seven, and two times brighter than they otherwise would that enabled astronomers to detect the galaxy more efficiently and with greater confidence.

“This cluster does what no manmade telescope can do,” said Marc Postman, also from STScI. “Without the magnification, it would require a Herculean effort to observe this galaxy.”

MACS0647-JD is just a fraction of the size of our Milky Way galaxy, and is so small it may not even be a fully formed galaxy. Data show the galaxy is less than 600 light-years wide. Based on observations of somewhat closer galaxies, astronomers estimate that a typical galaxy of a similar age should be about 2,000 light-years wide. For comparison, the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy companion to the Milky Way, is 14,000 light-years wide. Our Milky Way is 150,000 light-years across.

Loading player…

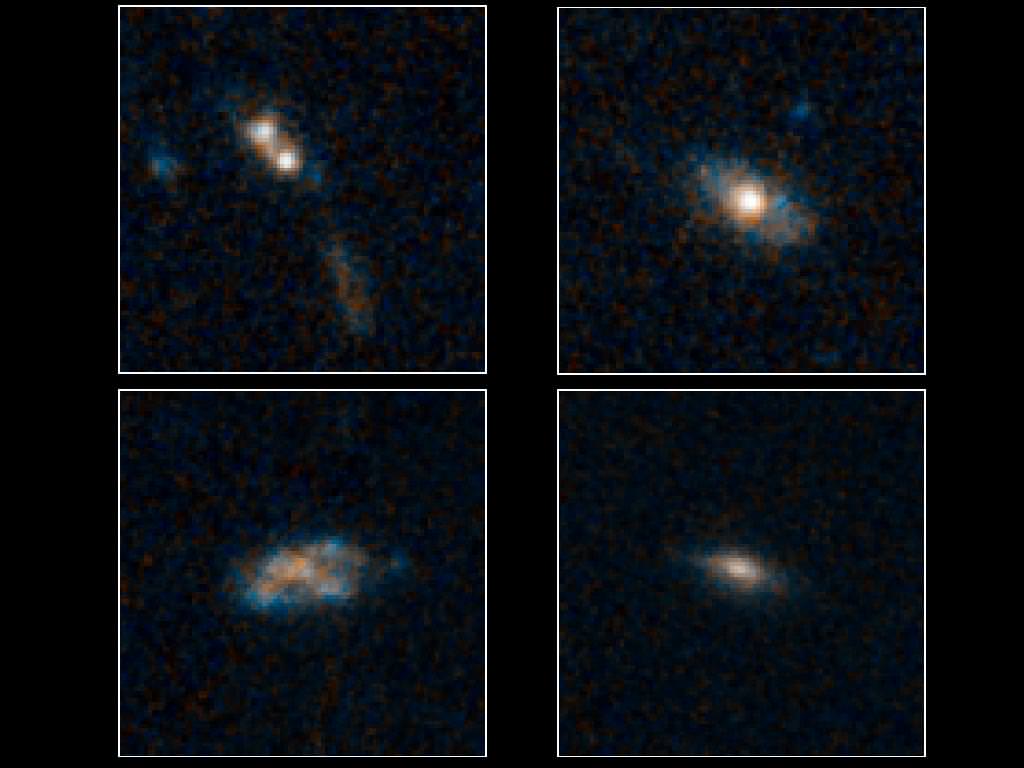

The galaxy was observed with 17 filters, spanning near-ultraviolet to near-infrared wavelengths, using Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) and Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). Coe discovered the galaxy in February while poring over a catalogue of thousands of gravitationally lensed objects found in Hubble observations of 17 clusters in the CLASH survey. But the galaxy appeared only in the two reddest filters.

“So either MACS0647-JD is a very red object, only shining at red wavelengths, or it is extremely distant and its light has been ‘redshifted’ to these wavelengths, or some combination of the two,” Coe said. “We considered this full range of possibilities.”

The CLASH team identified multiple images of eight galaxies lensed by the galaxy cluster. Their positions allowed the team to produce a map of the cluster’s mass, which is primarily composed of dark matter. Dark matter is an invisible form of matter that makes up the bulk of the universe’s mass. “It’s like a big puzzle,” said Coe. “We have to arrange the mass in the cluster so that it deflects the light of each galaxy to the positions observed.” The team’s analysis revealed that the cluster’s mass distribution produced three lensed images of MACS0647-JD at the positions and relative brightness observed in the Hubble image.

Coe and his collaborators spent months systematically ruling out these other alternative explanations for the object’s identity, including red stars, brown dwarfs, and red (old or dusty) galaxies at intermediate distances from Earth. They concluded that a very distant galaxy was the correct explanation.

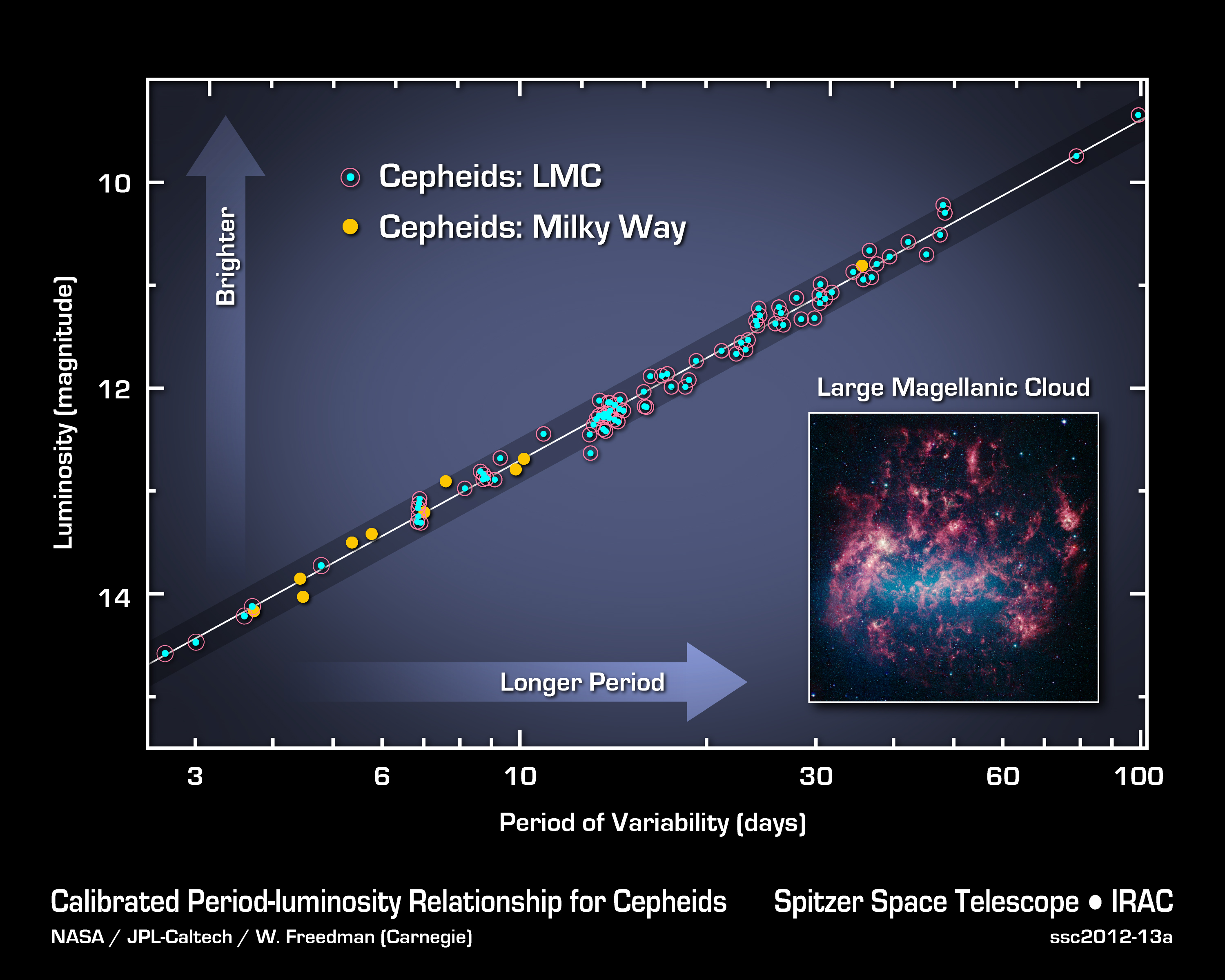

Redshift is a consequence of the expansion of space over cosmic time. Astronomers study the distant universe in near-infrared light because the expansion of space stretches ultraviolet and visible light from galaxies into infrared wavelengths. Coe estimates MACS0647-JD has a redshift of 11, the highest yet observed.

Images of the galaxy at longer wavelengths obtained with the Spitzer Space Telescope played a key role in the analysis. If the object were intrinsically red, it would appear bright in the Spitzer images. Instead, the galaxy barely was detected, if at all, indicating its great distance. The research team plans to use Spitzer to obtain deeper observations of the galaxy, which should yield confident detections as well as estimates of the object’s age and dust content.

MACS0647-JD galaxy, however, may be too far away for any current telescope to confirm the distance based on spectroscopy, which spreads out an object’s light into thousands of colors. Nevertheless, Coe is confident the fledgling galaxy is the new distance champion based on its unique colors and the research team’s extensive analysis. “All three of the lensed galaxy images match fairly well and are in positions you would expect for a galaxy at that remote distance when you look at the predictions from our best lens models for this cluster,” Coe said.

The new distance champion is the second remote galaxy uncovered in the CLASH survey, a multi-wavelength census of 25 hefty galaxy clusters with Hubble’s ACS and WFC3. Earlier this year, the CLASH team announced the discovery of a galaxy that existed when the universe was 490 million years old, 70 million years later than the new record-breaking galaxy. So far, the survey has completed observations for 20 of the 25 clusters.

The team hopes to use Hubble to search for more dwarf galaxies at these early epochs. If these infant galaxies are numerous, then they could have provided the energy to burn off the fog of hydrogen that blanketed the universe, a process called re-ionization. Re-ionization ultimately made the universe transparent to light.

Read the team’s paper (pdf).

Sources: HubbleSite, ESA Hubble