Something’s up in cosmology that may force us to re-write a few textbooks. It’s all centred around the measurement of the expansion of the Universe, which is, obviously, a pretty key part of our understanding of the cosmos.

The expansion of the Universe is regulated by two things: Dark Energy and Dark Matter. They’re like the yin and yang of the cosmos. One drives expansion, while one puts the brakes on expansion. Dark Energy pushes the universe to continually expand, while Dark Matter provides the gravity that retards that expansion. And up until now, Dark Energy has appeared to be a constant force, never wavering.

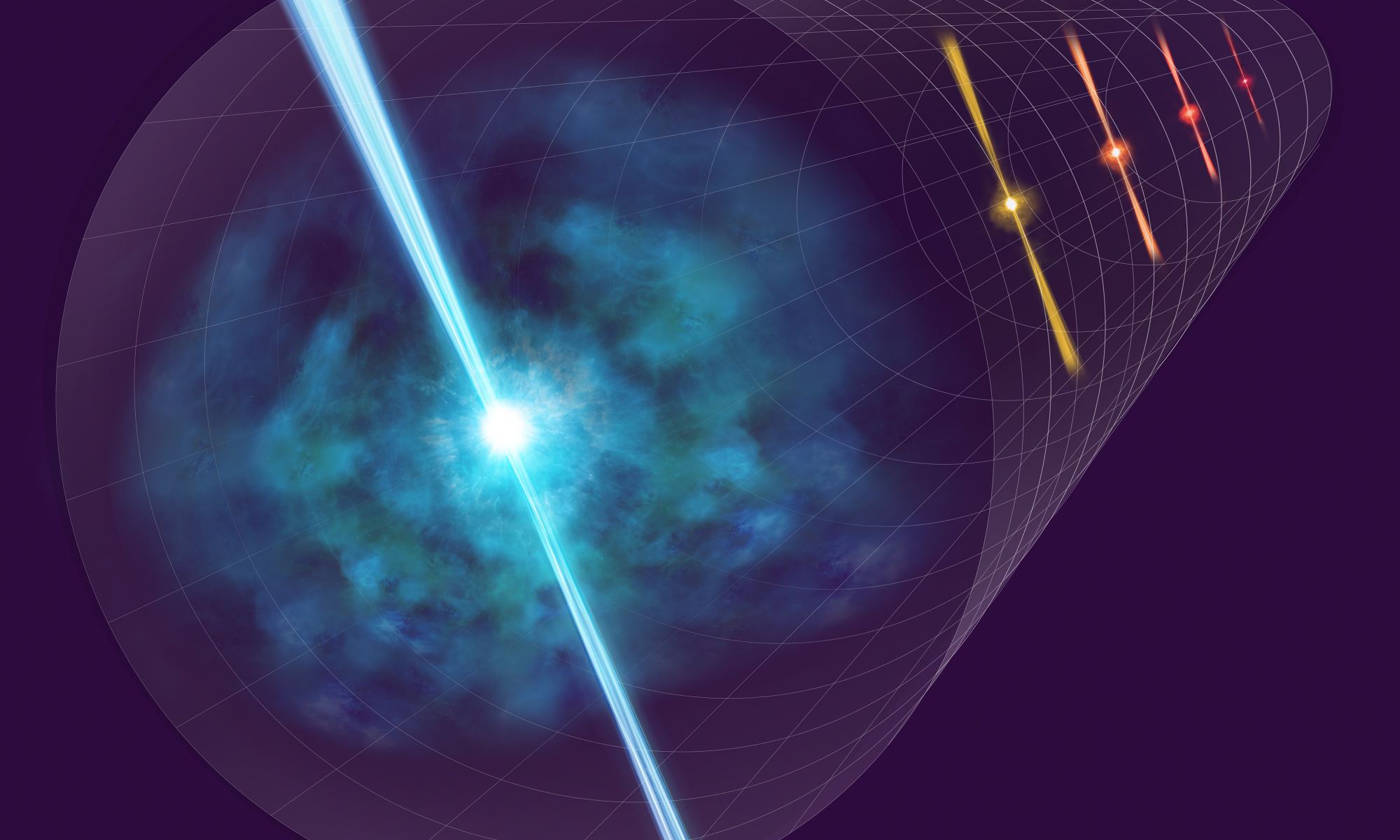

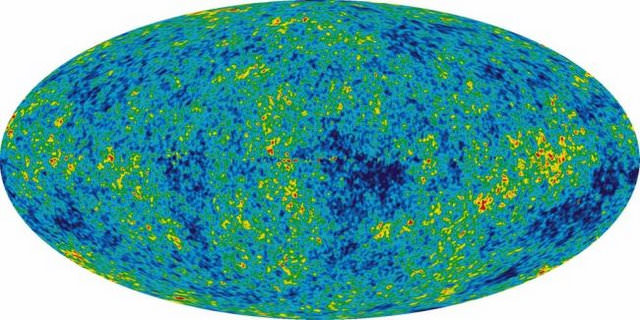

How is this known? Well, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) is one way the expansion is measured. The CMB is like an echo from the early days of the Universe. It’s the evidence left behind from the moment about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, when the rate of expansion of the Universe stabilized. The CMB is the source for most of what we know of Dark Energy and Dark Matter. (You can hear the CMB for yourself by turning on a household radio, and tuning into static. A small percentage of that static is from the CMB. It’s like listening to the echo of the Big Bang.)

The CMB has been measured and studied pretty thoroughly, most notably by the ESA’s Planck Observatory, and by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP). The Planck, in particular, has given us a snapshot of the early Universe that has allowed cosmologists to predict the expansion of the Universe. But our understanding of the expansion of the Universe doesn’t just come from studying the CMB, but also from the Hubble Constant.

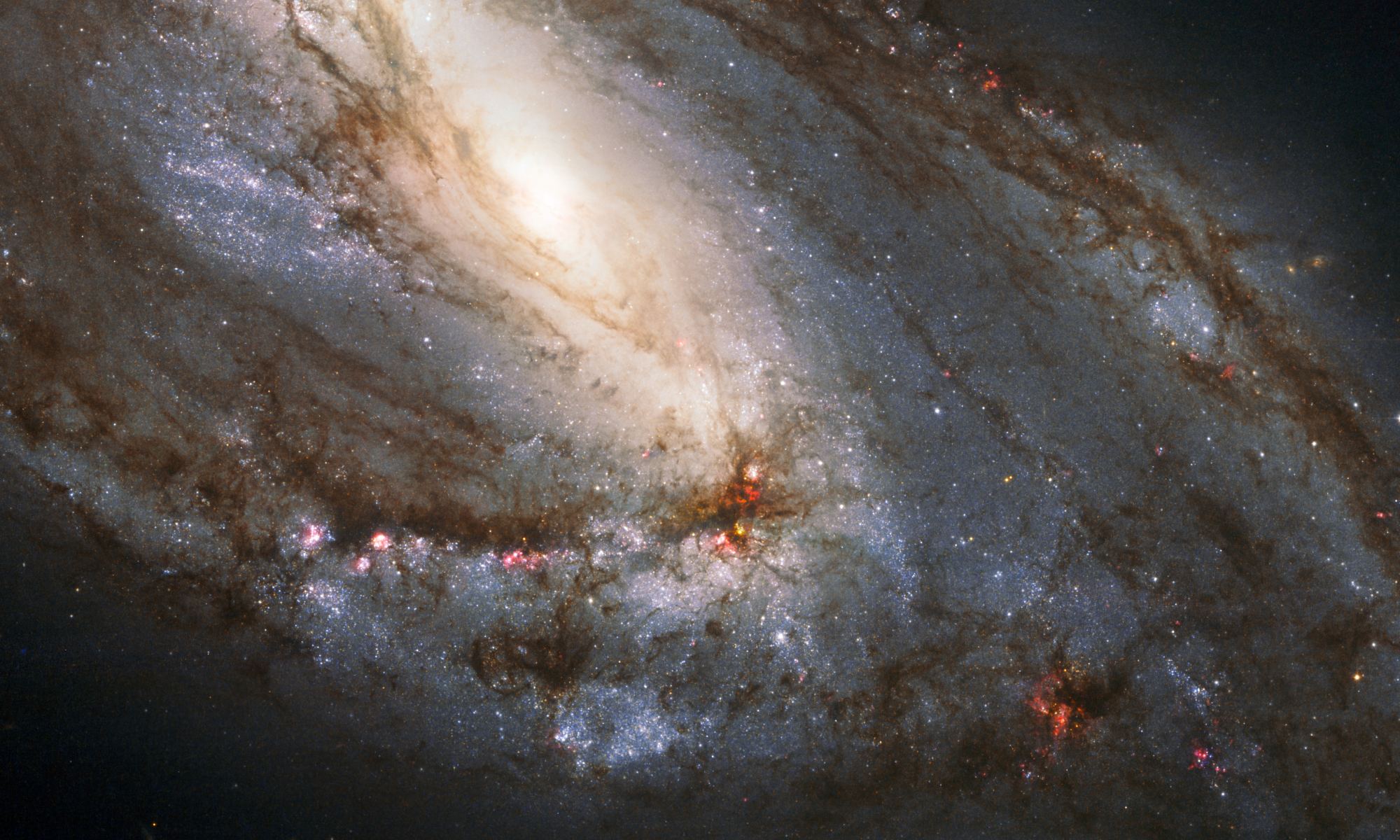

The Hubble Constant is named after Edwin Hubble, an American astronomer who observed that the expansion velocity of galaxies can be confirmed by their redshift. Hubble also observed Cepheid variable stars, a type of standard candle that gives us reliable measurements of distances between galaxies. Combining the two observations, the velocity and the distance, yielded a measurement for the expansion of the Universe.

So we’ve had two ways to measure the expansion of the Universe, and they mostly agree with each other. There’ve been discrepancies between the two of a few percentage points, but that has been within the realm of measurement errors.

But now something’s changed.

In a new paper, Dr. Adam Riess of Johns Hopkins University, and his team, have reported a more stringent measurement of the expansion of the Universe. Riess and his team used the Hubble Space Telescope to observe 18 standard candles in their host galaxies, and have reduced some of the uncertainty inherent in past studies of standard candles.

The result of this more accurate measurement is that the Hubble constant has been refined. And that, in turn, has increased the difference between the two ways the expansion of the Universe is measured. The gap between what the Hubble constant tells us is the rate of expansion, and what the CMB, as measured by the Planck spacecraft, tells us is the rate of expansion, is now 8%. And 8% is too large a discrepancy to be explained away as measurement error.

The fallout from this is that we may need to revise our standard model of cosmology to account for this, somehow. And right now, we can only guess what might need to be changed. There are at least a couple candidates, though.

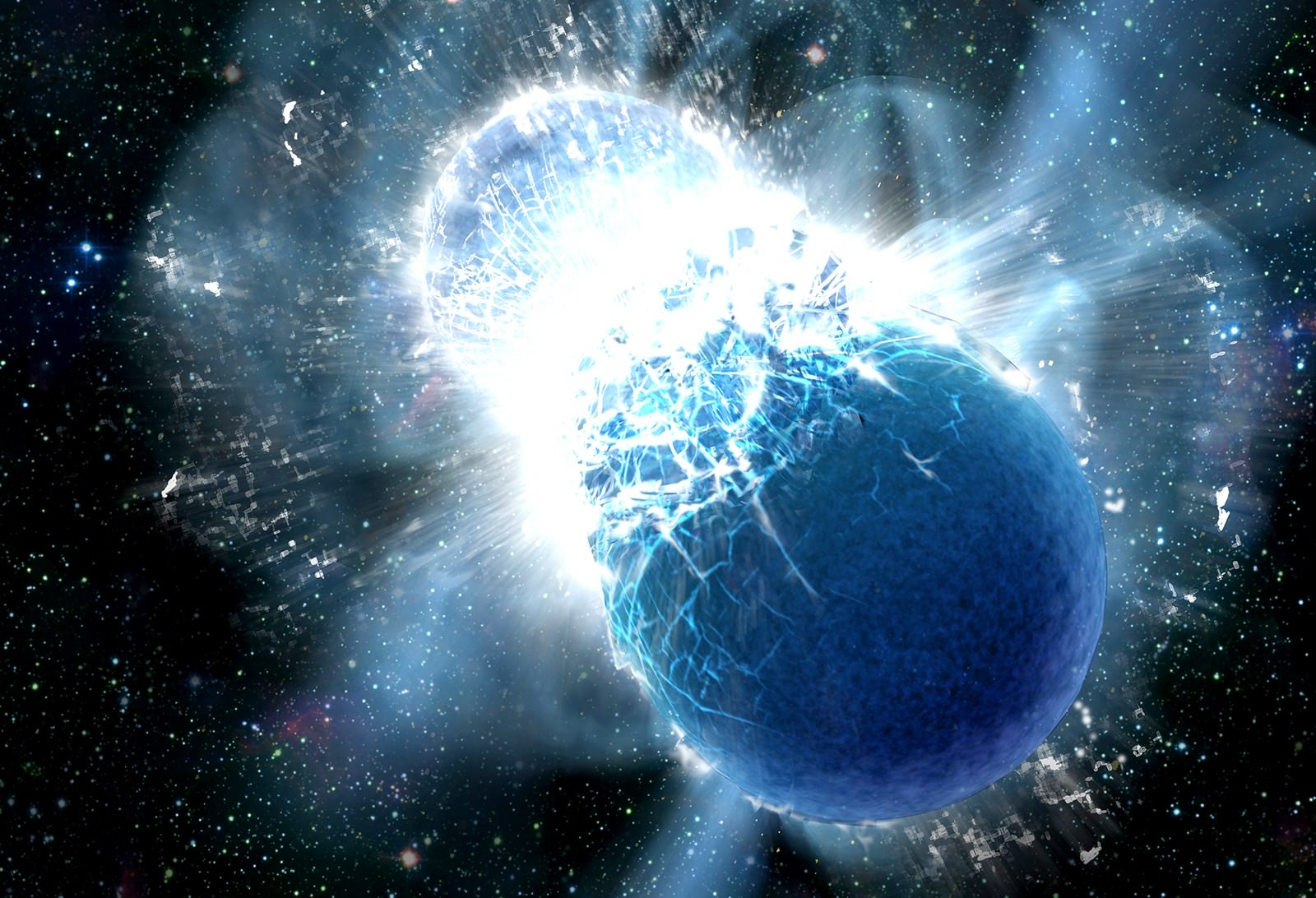

It might be centred around Dark Matter, and how it behaves. It’s possible that Dark Matter is affected by a force in the Universe that doesn’t act on anything else. Since so little is known about Dark Matter, and the name itself is little more than a placeholder for something we are almost completely ignorant about, that could be it.

Or, it could be something to do with Dark Energy. Its name, too, is really just a placeholder for something we know almost nothing about. Maybe Dark Energy is not constant, as we have thought, but changes over time to become stronger now than in the past. That could account for the discrepancy.

A third possibility is that standard candles are not the reliable indicators of distance that we thought they were. We’ve refined our measurements of standard candles before, maybe we will again.

Where this all leads is open to speculation at this point. The rate of expansion of the Universe has changed before; about 7.5 billion years ago it accelerated. Maybe it’s changing again, right now in our time. Since Dark Energy occupies so-called empty space, maybe more of it is being created as expansion continues. Maybe we’re reaching another tipping or balancing point.

The only thing certain is that it is a mystery. One that we are driven to understand.