Star formation is well understood when it happens in the populous centers of galaxies. From our vantage point on Earth, within the Milky Way, we see it happening all around us. But when newborn stars are birthed in the empty outskirts of galactic space, it requires a new kind of explanation. At the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Association yesterday, astronomers announced that they have observed, for the first time, the unique molecular clouds that give rise to star formation near the remote edges of galaxies.

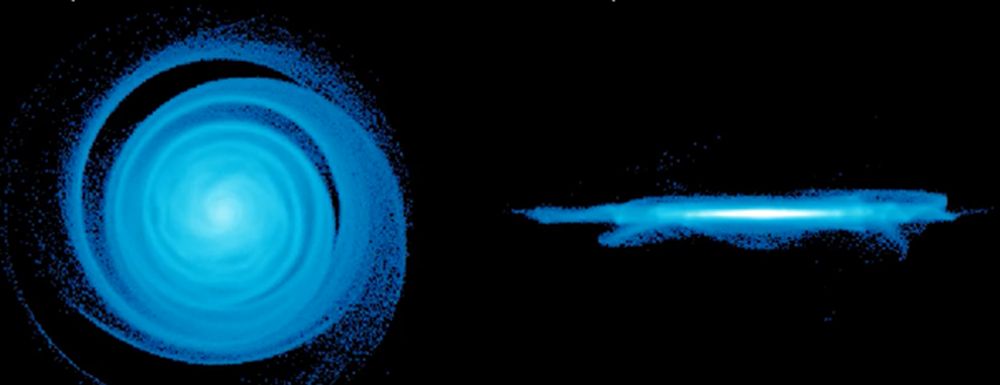

Continue reading “Young Stars in the Outskirts of Galaxies Finally Have an Explanation”The Oldest Known Spiral Galaxy Has Ripples Like the Surface of a Pond

Astronomers have detected pond-like ripples across the gaseous disk of an ancient galaxy. What caused the ripples, and what do they tell us about the distant galaxy’s formation and evolution? And whatever happened, how has it affected the galaxy and its main job: forming stars?

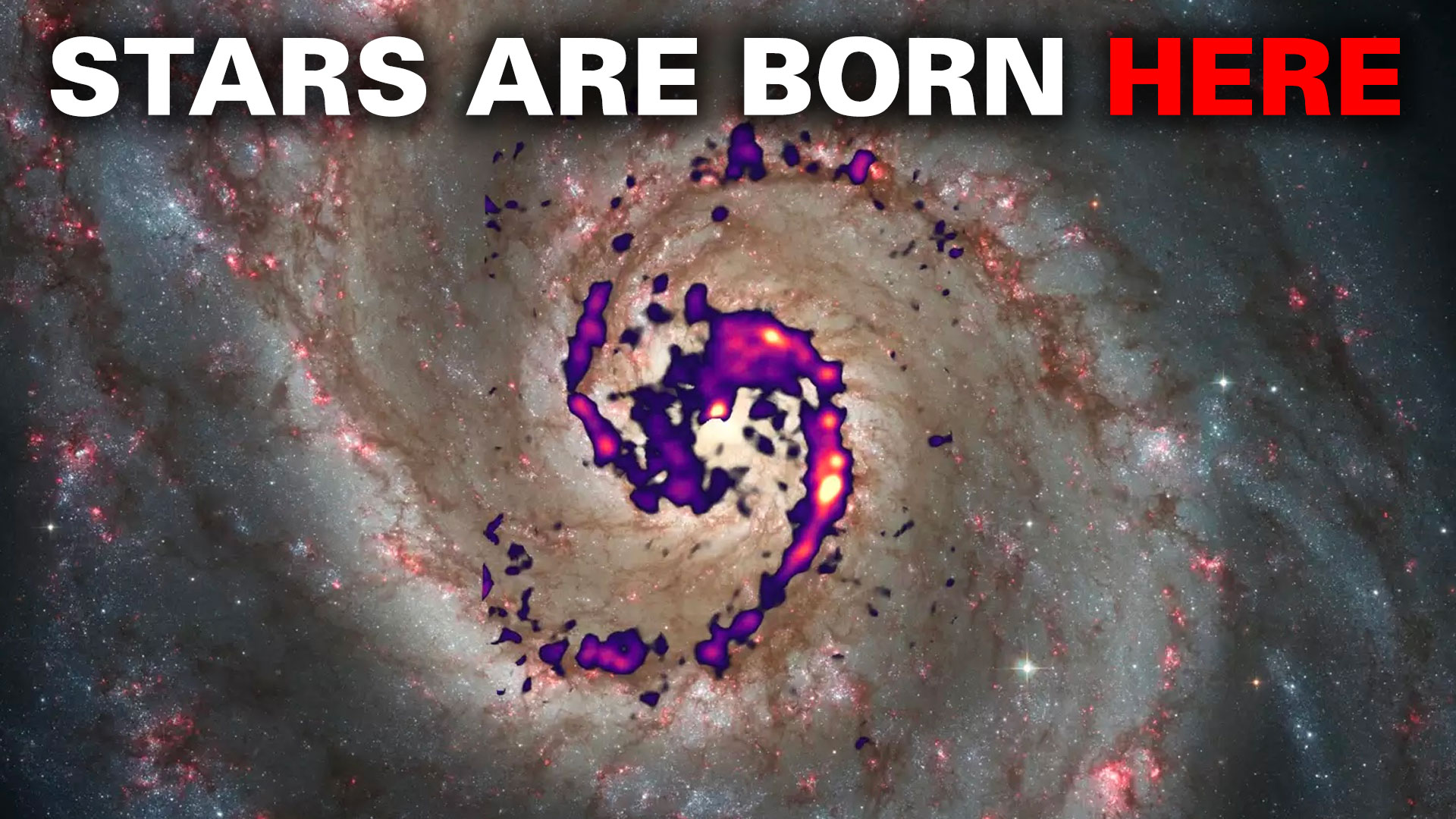

Continue reading “The Oldest Known Spiral Galaxy Has Ripples Like the Surface of a Pond”Astronomers Find the Birthplaces of Stars in the Whirlpool Galaxy

Understanding how star-forming works at a galactic scale is challenging in our Milky Way. While we have a general understanding of the layout of our galaxy, we can’t see all of the details head-on like we would want to if we were exploring a single galaxy for details of star formation. Luckily, we have a pretty good view of the entirety of one of the most famous galaxies in all of astronomy – M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy. Now, a team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy has completed a survey of molecules throughout the galaxy and developed a map of potential star-forming regions.

Continue reading “Astronomers Find the Birthplaces of Stars in the Whirlpool Galaxy”JWST Reveals Protoplanetary Disks in a Nearby Star Cluster

The Orion Nebula is a favourite among stargazers, certainly one of mine. It’s a giant stellar nebula out of which, hot young stars are forming. Telescopically to the eye it appears as a grey/green haze of wonderment but cameras reveal the true glory of these star forming regions. The Sun was once part of such an object and astronomers have been probing their secrets for decades. Now, a new paper presents the results from a detailed study from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) that has been exploring planet forming disks around stars in the Lobster Nebula.

Continue reading “JWST Reveals Protoplanetary Disks in a Nearby Star Cluster”What Can Slime Mold Teach Us About the Universe?

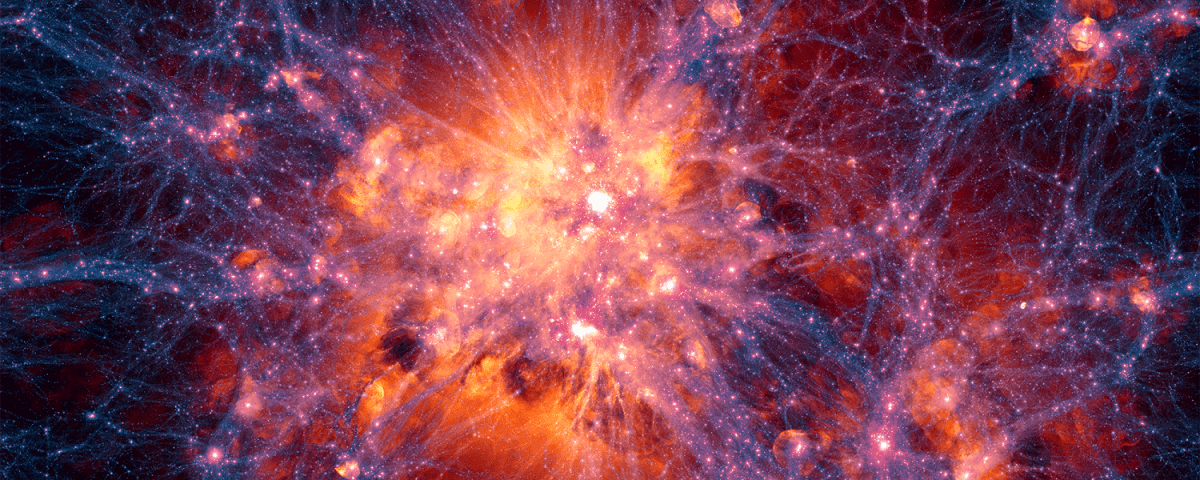

What can slime molds tell us about the large-scale structure of the Universe and the evolution of galaxies? These things might seem incongruous, yet both are part of nature, and Earthly slime molds seem to have something to tell us about the Universe itself. Vast filaments of gas threading their way through the Universe have a lot in common with slime molds and their tubular networks.

Continue reading “What Can Slime Mold Teach Us About the Universe?”Supermassive Black Holes Shut Down Star Formation During Cosmic Noon

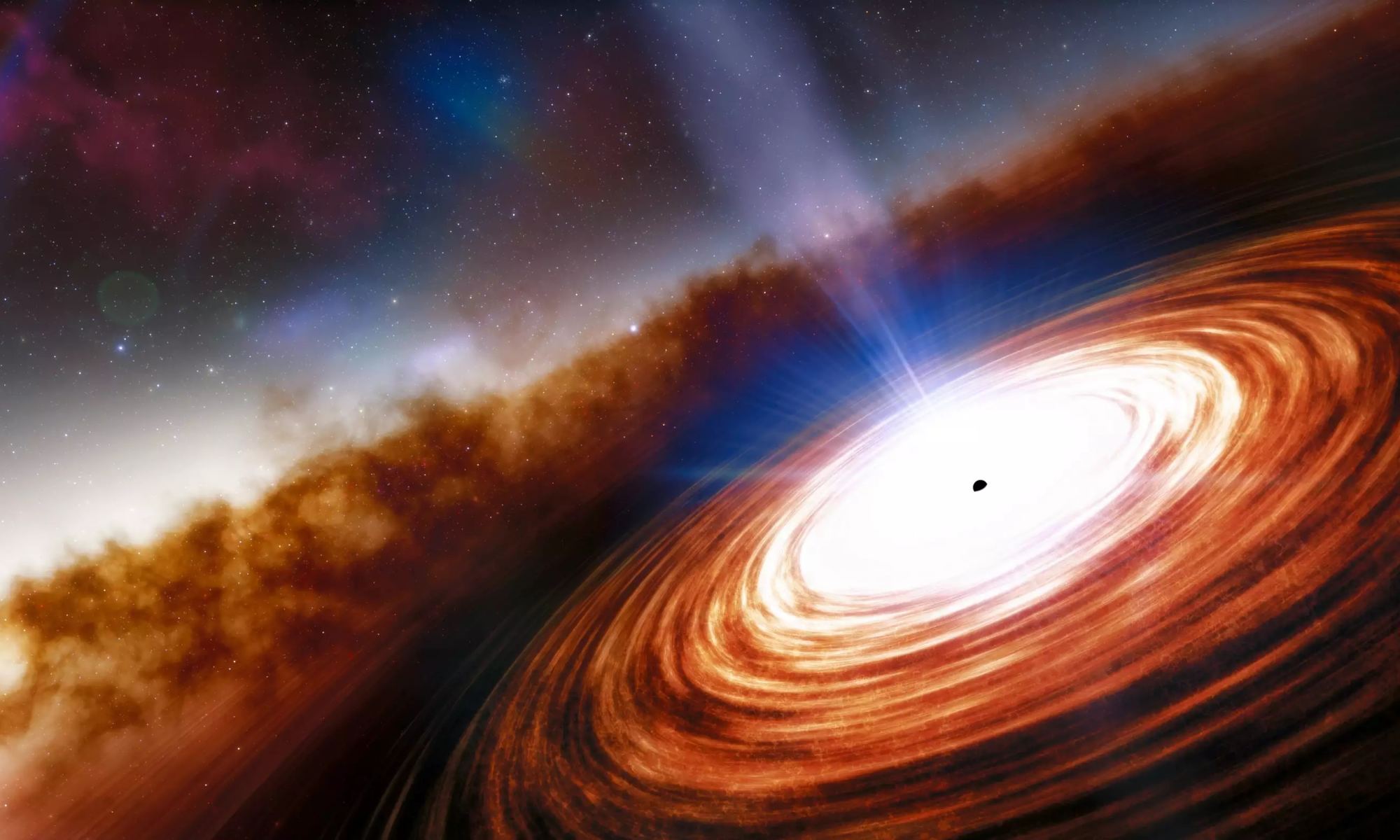

Since it became operational almost two years ago, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has produced countless breathtaking images of the Universe and enabled fresh insights into how it evolved. In particular, the telescope’s instruments are optimized for studying the cosmological epoch known as Cosmic Dawn, ca. 50 million to one billion years after the Big Bang when the first stars, black holes, and galaxies in the Universe formed. However, astronomers are also getting a better look at the epoch that followed, Cosmic Noon, which lasted from 2 to 3 billion years after the Big Bang.

During this time, the first galaxies grew considerably, most stars in the Universe formed, and many galaxies with supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at their centers became incredibly luminous quasars. Scientists have been eager to get a better look at galaxies dated to this period so they can see how SMBHs affected star formation in young galaxies. Using near-infrared data obtained by Webb, an international team of astronomers made detailed observations of over 100 galaxies as they appeared 2 to 4 billion years after the Big Bang, coinciding with Cosmic Noon.

Continue reading “Supermassive Black Holes Shut Down Star Formation During Cosmic Noon”Astronomers Want JWST to Study the Milky Way Core for Hundreds of Hours

To understand the Universe, we need to understand the extreme processes that shape it and drive its evolution. Things like supermassive black holes (SMBHs,) supernovae, massive reservoirs of dense gas, and crowds of stars both on and off the main sequence. Fortunately there’s a place where these objects dwell in close proximity to one another: the Milky Way’s Galactic Center (GC.)

Continue reading “Astronomers Want JWST to Study the Milky Way Core for Hundreds of Hours”Feast Your Eyes on this Star-Forming Region, Thanks to the JWST

Nature is stingy with its secrets. That’s why humans developed the scientific method. Without it, we’d still be ignorant and living in a world dominated by superstitions.

Astrophysicists have made great progress in understanding how stars form, thanks to the scientific method. But there’s a lot they still don’t know. That’s one of the reasons NASA built the James Webb Space Telescope: to coerce Nature into surrendering its deeply-held secrets.

Continue reading “Feast Your Eyes on this Star-Forming Region, Thanks to the JWST”Compare Images of a Galaxy Seen by Both Hubble and JWST

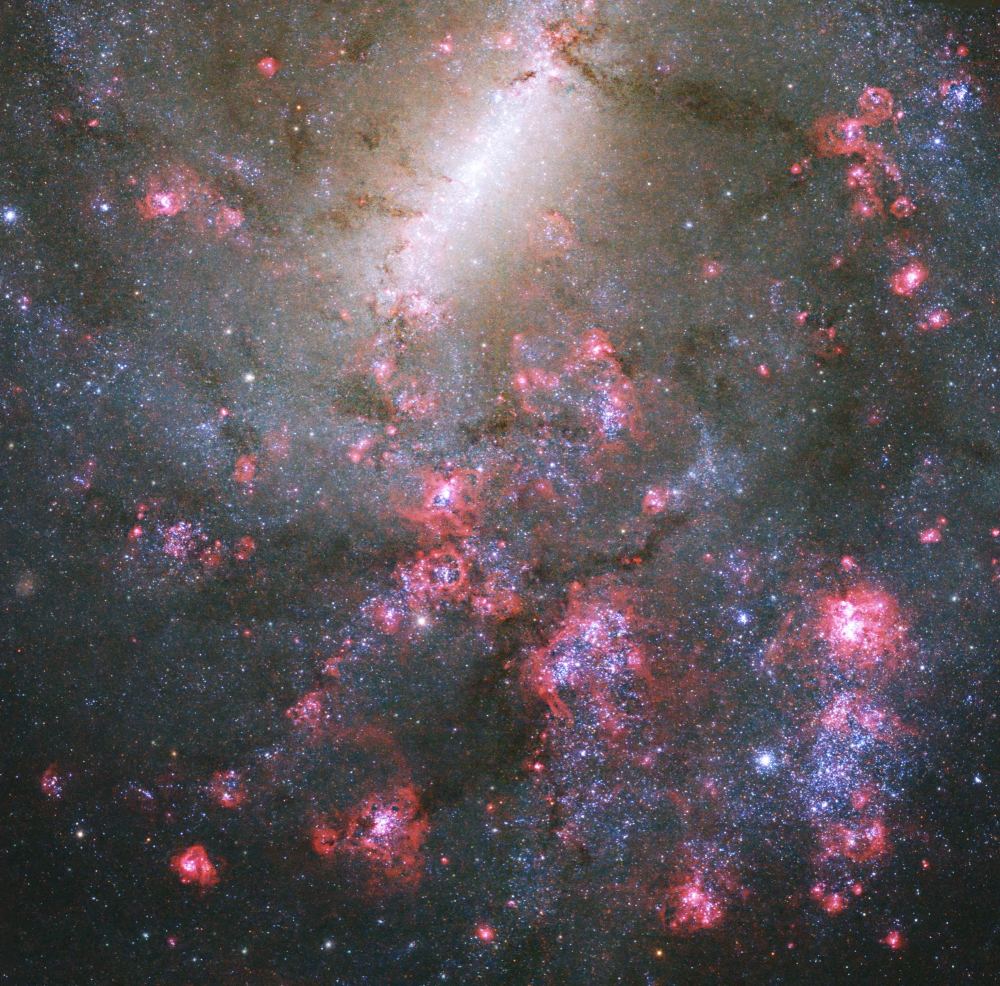

The James Webb Space Telescope is widely considered to be better than the Hubble Space Telescope. But the JWST doesn’t replace its elder sibling; it’s the Hubble’s successor. The Hubble is nowhere near ready to retire. It’s still a powerful science instrument with lots to contribute. Comparing images of the same object, NGC 5068, from both telescopes illustrates each one’s value and how they can work together.

Continue reading “Compare Images of a Galaxy Seen by Both Hubble and JWST”Galaxies Breathe Gas, and When They Stop, No More Stars Form

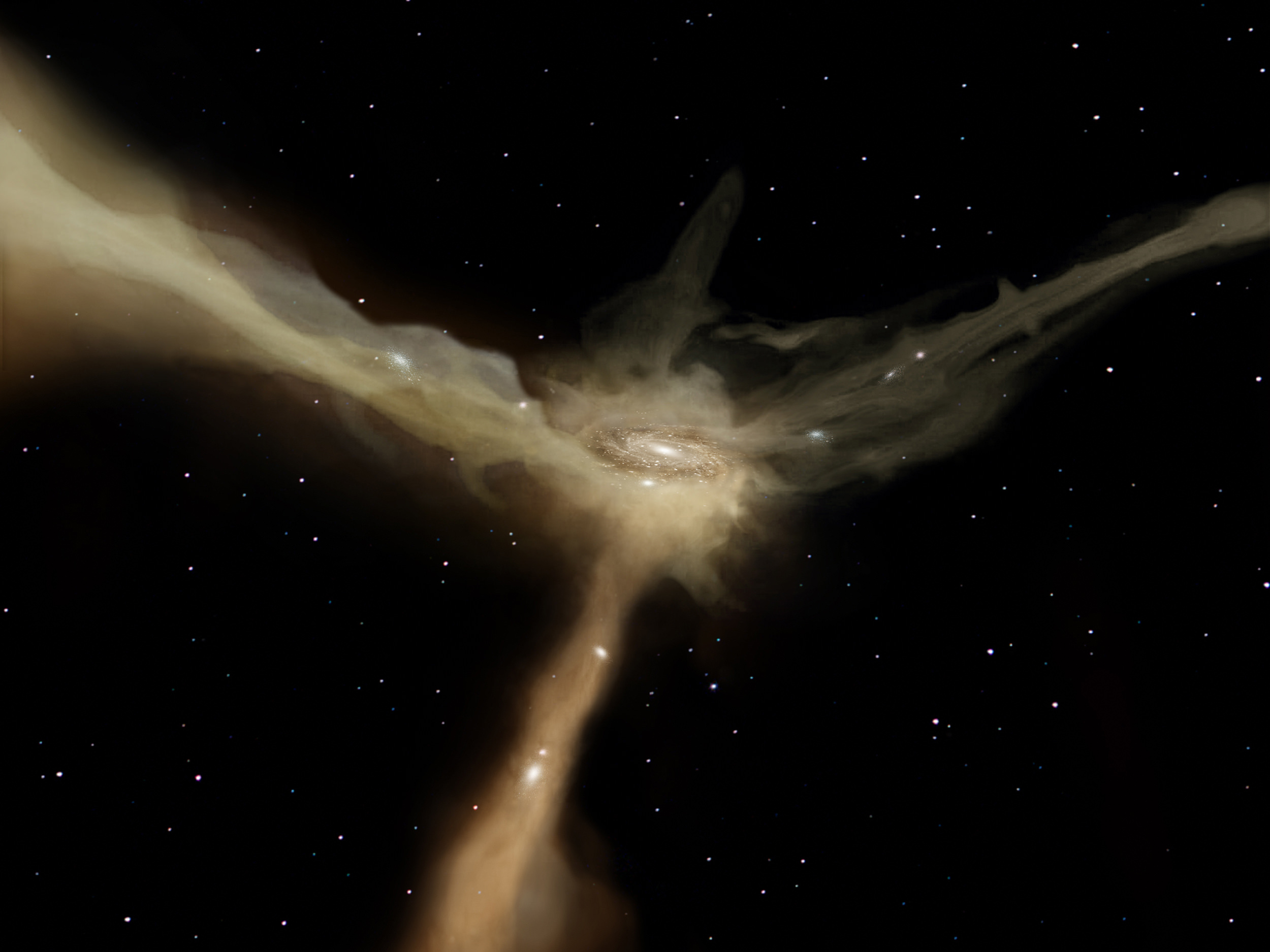

For most of the history of astronomy, all we could see were stars. We could see them individually, in clusters, in nebulae, and in fuzzy blobs that we thought were clumps of stars but were actually galaxies. The thing is, most of what’s out there is much harder to see than stars and galaxies. It’s gas.

Now that astronomers can see gas better than ever, we can see how galaxies breathe it in and out. When they stop breathing it, stars stop forming.

Continue reading “Galaxies Breathe Gas, and When They Stop, No More Stars Form”