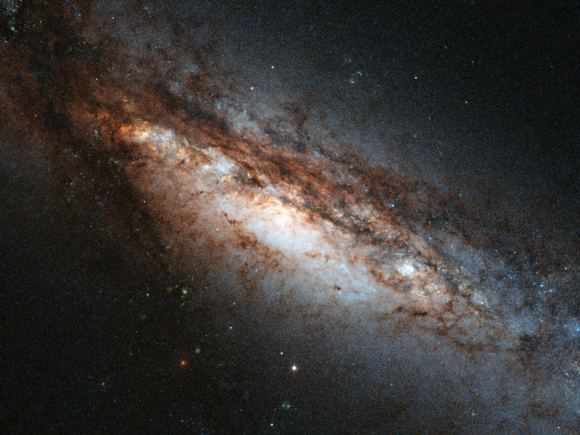

In the 1970s, astronomers discovered that a particularly large black hole (Sagittarius A*) existed at the center of our galaxy. In time, they came to understand that similar Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs) existed in the center of most massive galaxies. The presence of these black holes was also what differentiated galaxies that had particularly luminous cores – aka. Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) – from those that didn’t.

Since that time, astronomers and cosmologists have pondered what role SMBHs have on galactic evolution, with some venturing that they have a profound impact on star formation. And thanks to a recent study by an international team of astronomers, there is now direct evidence for a correlation between and SMBH and a galaxy’s star formation. In fact, the team demonstrated that a black hole’s mass could determine when star formation in a galaxy will end.

The study, titled “Black-Hole-Regulated Star Formation in Massive Galaxies“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. Led by Ignacio Martín-Navarro, a Marie Curie Fellow at the University of California Observatories, the study team also consisted of members from the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy and the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias.

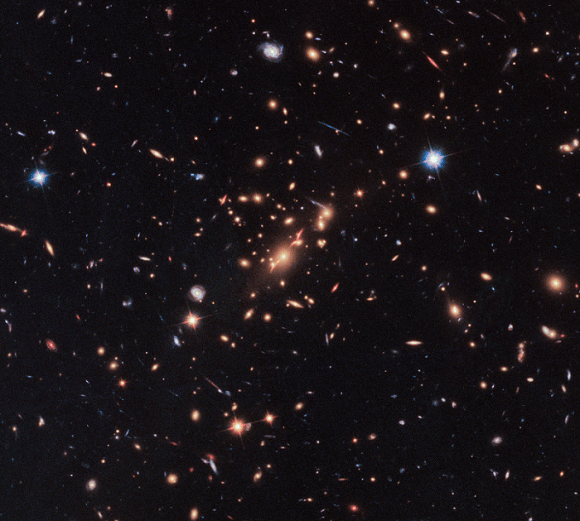

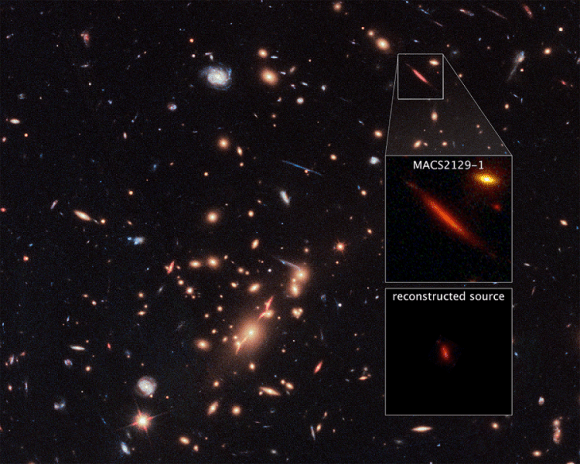

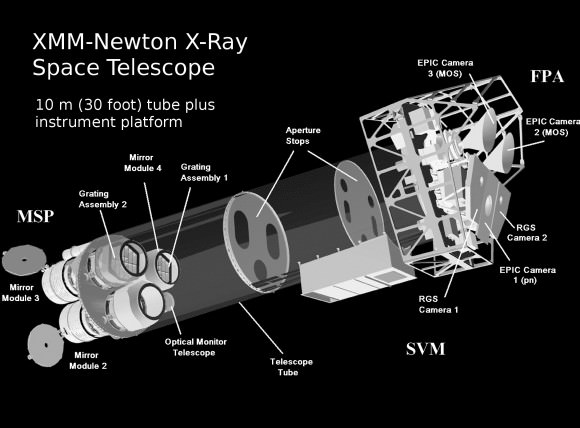

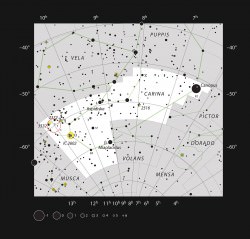

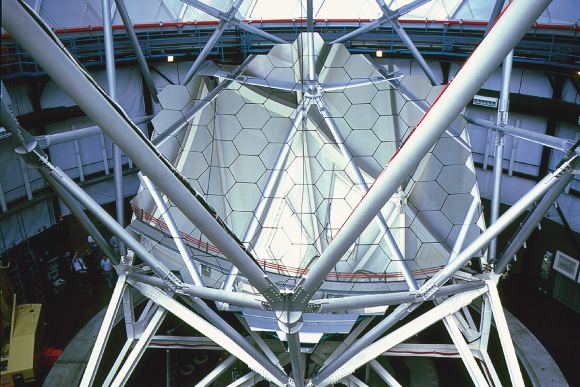

For the sake of their study, the team relied on data gathered the Hobby-Eberle Telescope Massive Galaxy Survey in 2015. This systematic survey used the 10m Hobby-Eberly Telescope (HET) at the McDonald Observatory to conduct an optical long-slit spectroscopic survey of over 1000 galaxies. This survey not only provided spectra for these galaxies, but also produced direct mass measurements of the central black holes for 74 of these galaxies.

Using this data, Martín-Navarro and his colleagues found the first observational evidence for a direct correlation between the mass of a galaxy’s central black hole and its history of star formation. While astrophysicists have been operating under this assumption for decades, the proof was missing until now. As Jean Brodie, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz and a coauthor of the paper, said in a UCSC press release:

“We’ve been dialing in the feedback to make the simulations work out, without really knowing how it happens. This is the first direct observational evidence where we can see the effect of the black hole on the star formation history of the galaxy.”

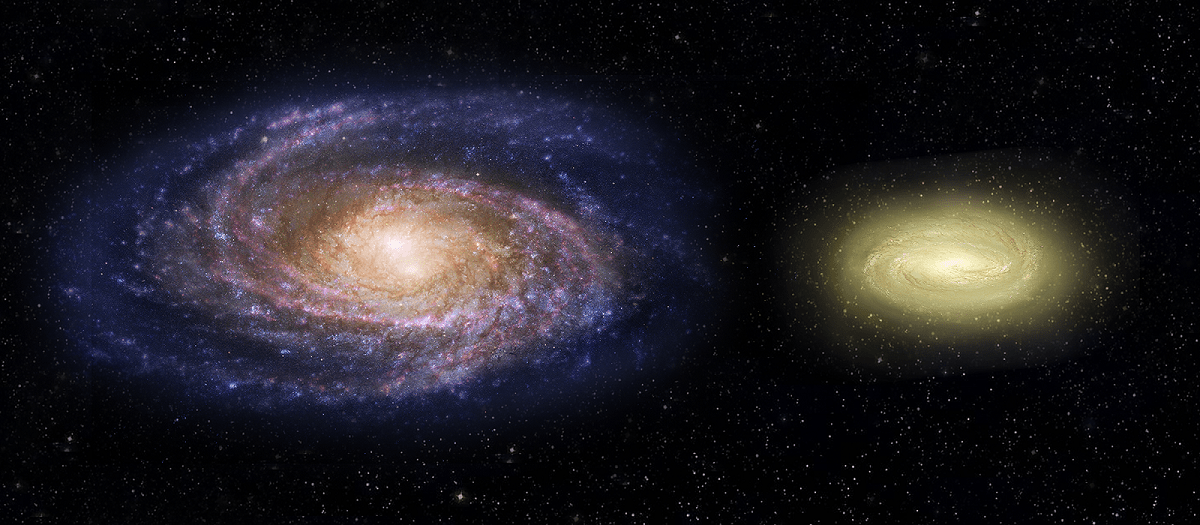

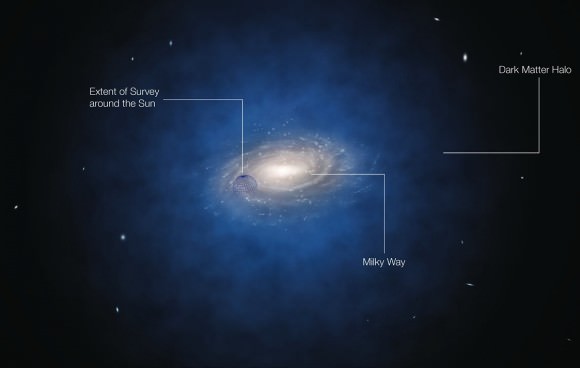

Roughly 15 years ago, the correlation between a SMBHs mass and the total mass of a galaxy’s stars was discovered, which led to a major unresolved question in astrophysical circles. While this correlation appeared to be a central feature of galaxies, it was unclear as to what could have caused it. How could the mass of a comparatively small and central black hole be related to the mass of billions of stars distributed throughout a galaxy?

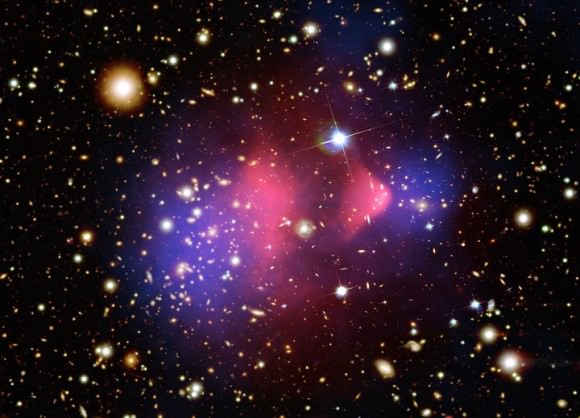

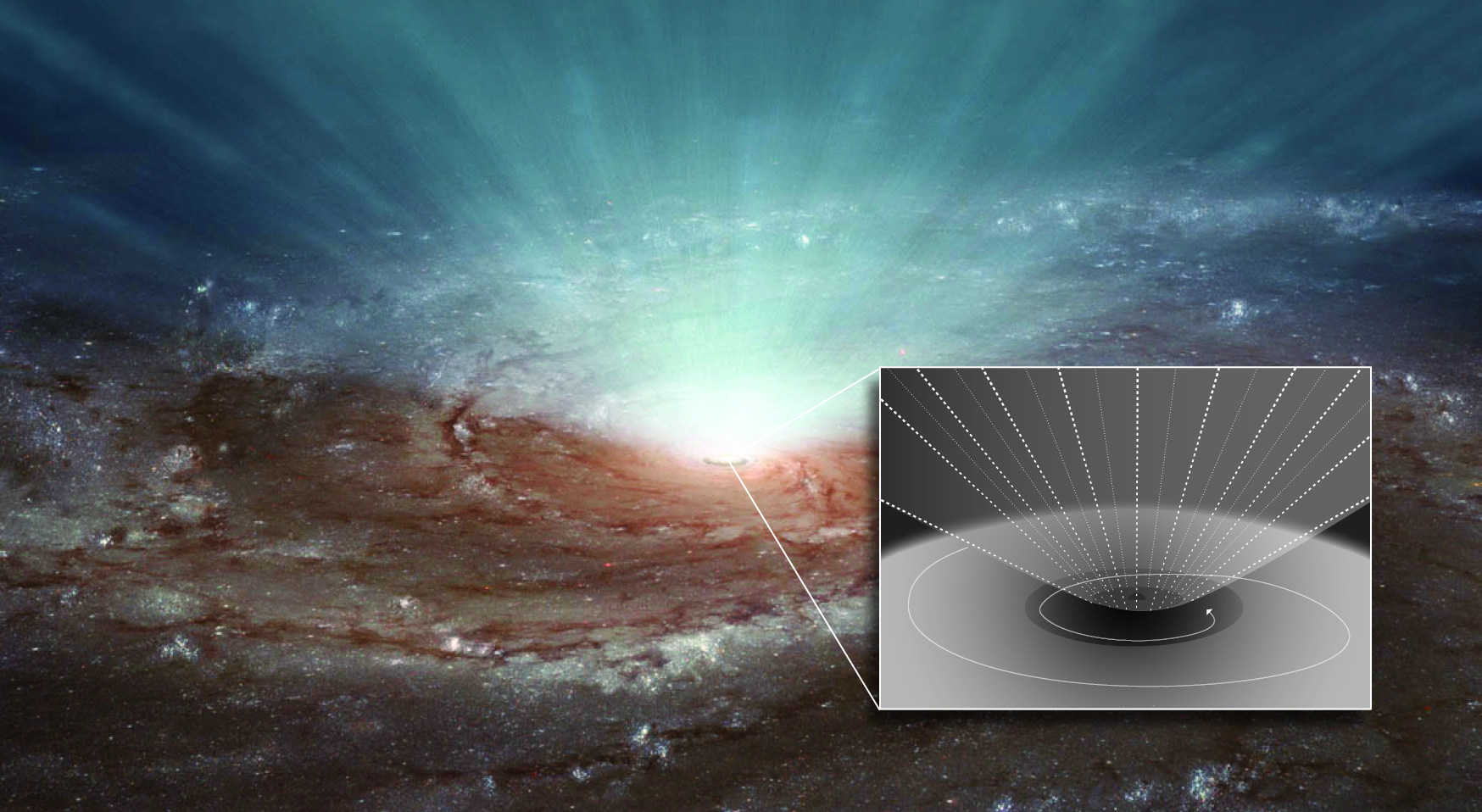

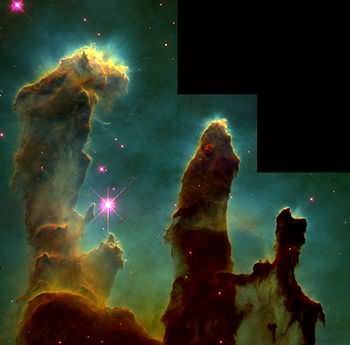

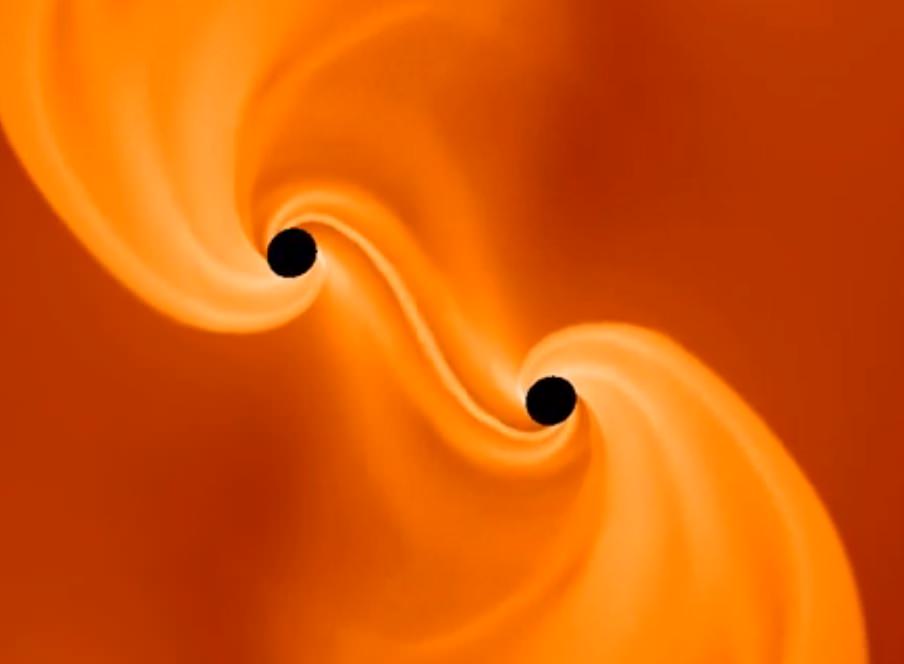

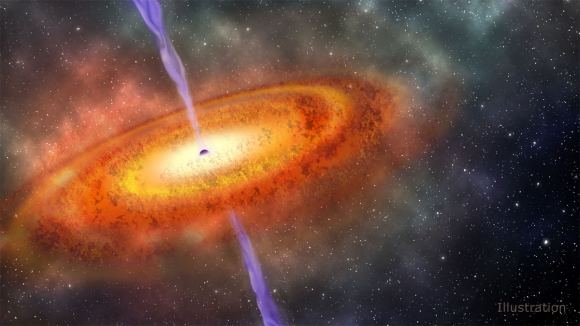

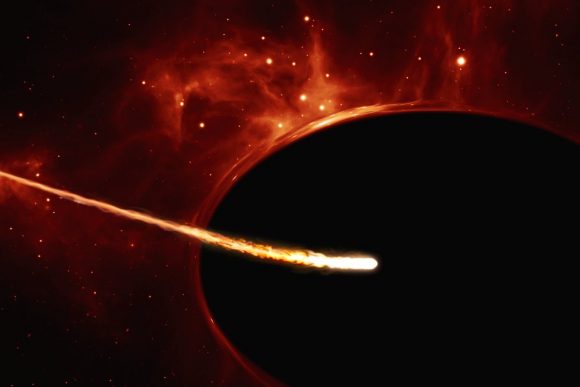

One possible explanation was that more massive galaxies collected larger amounts of gas, thus resulting in more stars and a more massive central black hole. However, astrophysicists also believed their was a feedback mechanism at work, where growing black holes inhibited the formation of stars in their vicinity. In short, when matter accretes on a central black hole, it sends out a tremendous amount of energy in the form of radiation and particle jets.

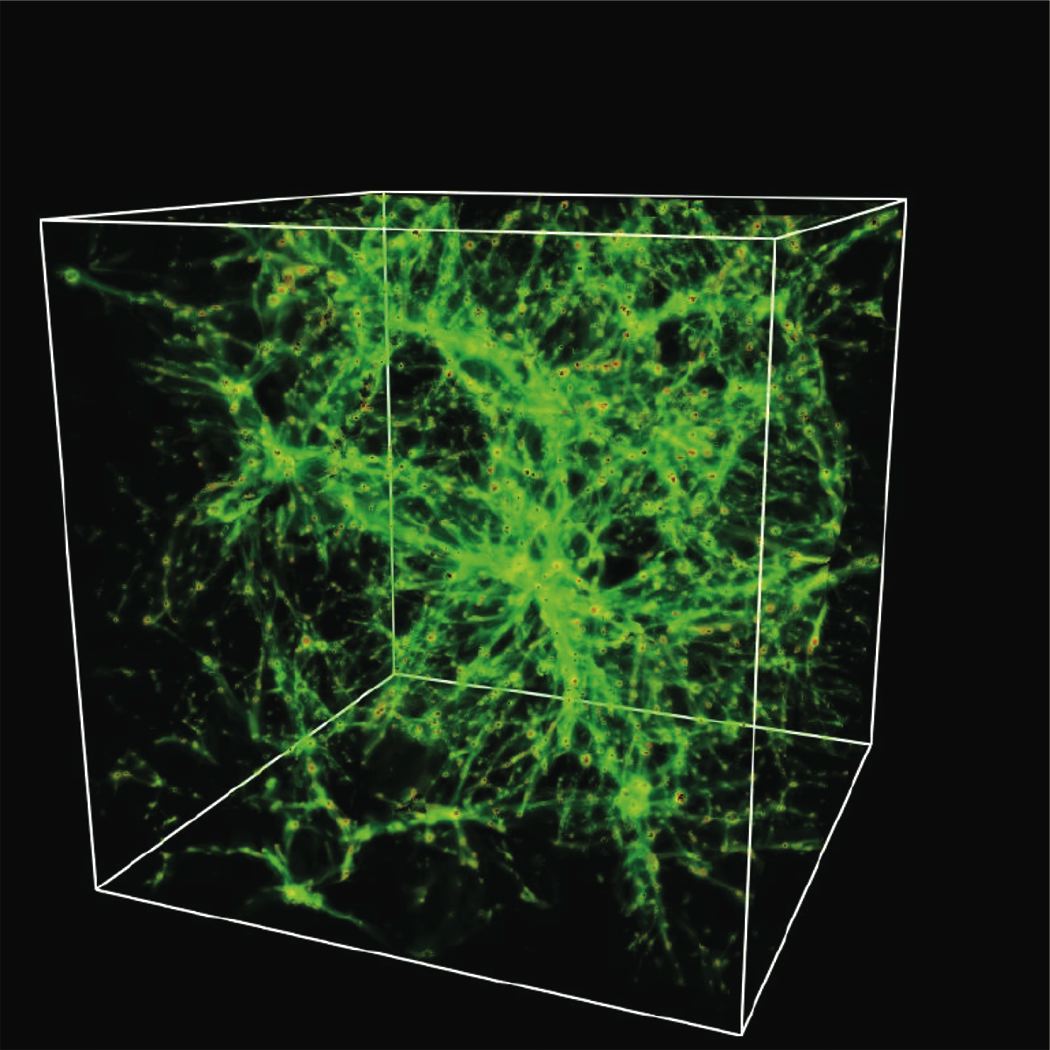

If this energy is transferred to gas and dust surrounding the core of the galaxy, stars will be less likely to form in this region since gas and dust need to be cold in order to undergo areas of collapse. For years, feedback of this kind has been included in cosmological simulations to explain the observed star-formation rates in galaxies. According to these same simulations, minus this mechanism, galaxies would form far more stars than have been observed.

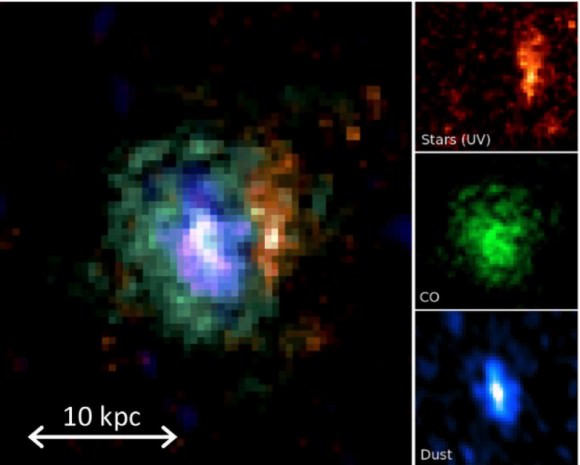

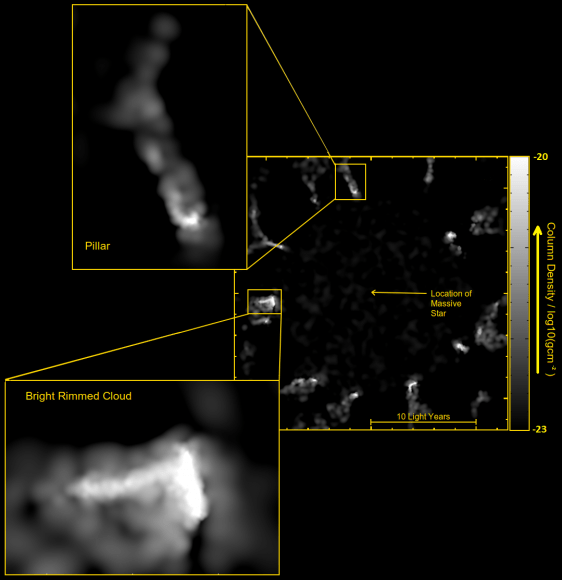

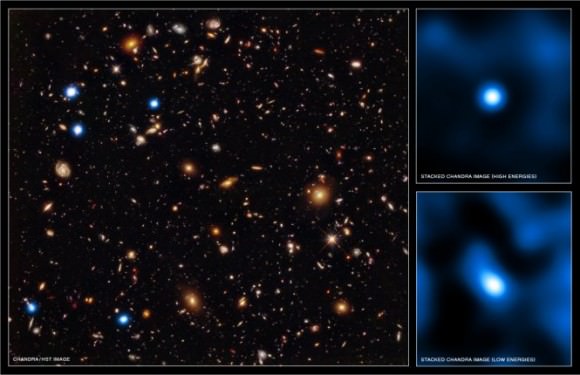

However, no direct evidence of this phenomena had previously been available. The first step to obtaining some was to reproduce the stellar formation histories of the 74 target galaxies used for the study. Martín-Navarro and his colleagues did this by subjecting spectra obtained from each of these galaxies to computational techniques that looked for the best combination of stellar populations to fit the data.

In so doing, the team was able to reconstruct the history of star formation within the target galaxies for the past 12.5 billion years. After examining these histories, they noticed some predictable results, but also some rather significant differences. For starters, as predicted, the regions of around the galaxies’ central black holes demonstrated a clear dampening influence on the rate of star formation.

As predicted, there was also a clear correlation between the mass of the central black holes and stellar mass in these galaxies. However, the team also noted that in cases where stellar mass was slightly smaller than expected (relative to the mass of their central black holes), star formation rates were lower. In some other cases, galaxies had larger-than-expected stellar masses (again, relative to their black holes) and their star formation rates were higher.

This correlation was not only more consistent than that observed between black hole mass and stellar mass, it occurred independently of other factors (such as shape or density). As Martín-Navaro explained:

“For galaxies with the same mass of stars but different black hole mass in the center, those galaxies with bigger black holes were quenched earlier and faster than those with smaller black holes. So star formation lasted longer in those galaxies with smaller central black holes.”

They also noted that this correlation extends into the deep past, where the galaxies with supermassive central black holes have been consistently producing a comparatively low rate of stars for the past 12.5 billion years. This constitutes the first strong evidence for a direct, long-term connection between star formation and the existence of a central black hole in a galaxy.

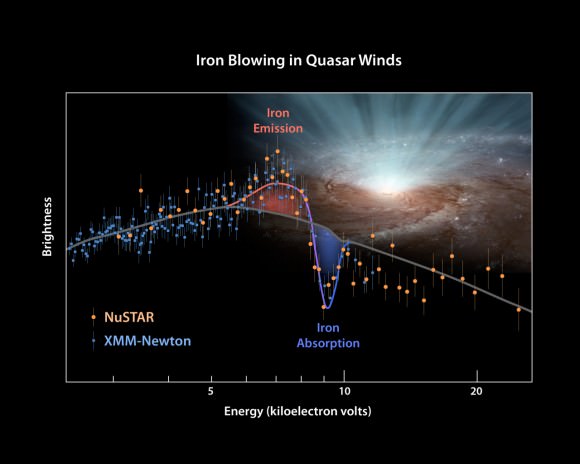

Another interesting takeaway from the study was the way it addressed possible correlations between AGN luminosity and star formation. In the past, other researchers have sought to find evidence of a link between the two, but without success. According to Martín-Navarro and his team, this may be because the time scales are incredibly different. Whereas star formation occurs over the course of eons, outbursts from AGNs occur over shorter intervals.

What’s more, AGNs are highly variable and their properties are dependent on a number of factors relating to their black holes – i.e. size, mass, rate of accretion, etc. “We used black hole mass as a proxy for the energy put into the galaxy by the AGN, because accretion onto more massive black holes leads to more energetic feedback from active galactic nuclei, which would quench star formation faster,” said Martin-Navarro.

Looking ahead, the team hopes to conduct further research and determine exactly how central black holes arrest star formation. At present, the possibility that it could be due to radiation or jets of gas heating up surrounding matter are not definitive. As Aaron Romanowsky, an astronomer at San Jose State University and UC Observatories, indicated:

“There are different ways a black hole can put energy out into the galaxy, and theorists have all kinds of ideas about how quenching happens, but there’s more work to be done to fit these new observations into the models.”

Part of determining how the Universe came to be is knowing what mechanisms were at play and the extent of their roles. With this latest study, astrophysicists and cosmologists can take comfort in the knowledge that they’ve been getting it right – at least in this case!