When you look into the night sky, you’re seeing tremendous distances away, even with your bare eyeball. But what’s the most distant object you can see with the unaided eye? And what if you get help with a pair of binoculars, a telescope, or even with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Standing at sea level, your head is at an altitude of 2 meters, and the horizon appears to be about 3 miles, or 5 km away. We’re able to see more distant objects if they’re taller, like buildings or mountains, or when we’re higher up in the air. If you get to an altitude of 20 meters, the horizon stretches out to about 11 km. But we can see objects in space which are even more distant with the naked eye. The Moon is 385,000 km away and the Sun is a whopping 150 million km. Visible all the way down here on Earth, the most distant object in the solar system we can see, without a telescope, is Saturn at 1.5 billion km away.

In the very darkest conditions, the human eye can see stars at magnitude 6.5 or greater. Which works about to about 9,000 individual stars. Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, is 8.6 light years. The most distant bright star, Deneb, is about 1500 light years away from Earth. If someone was looking back at us, right now, they could be seeing the election of the 52nd pope, St. Hormidas, in the 6th Century.

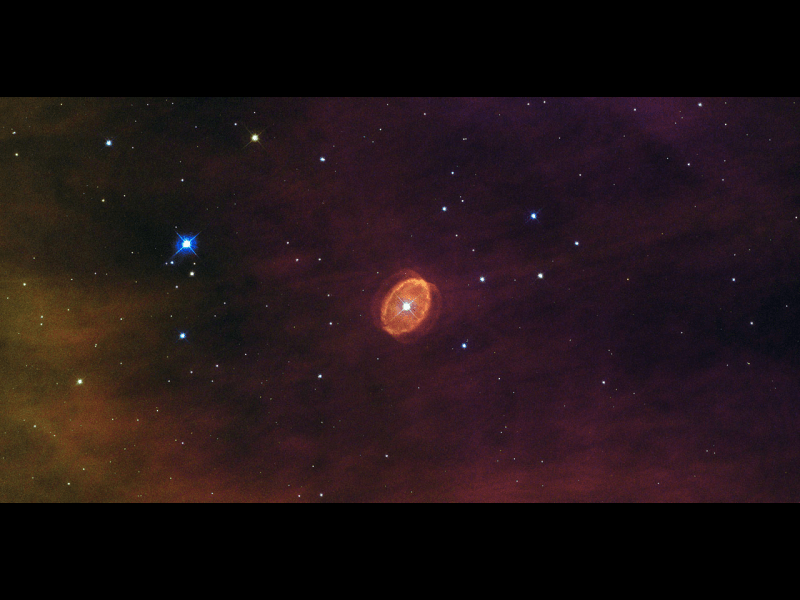

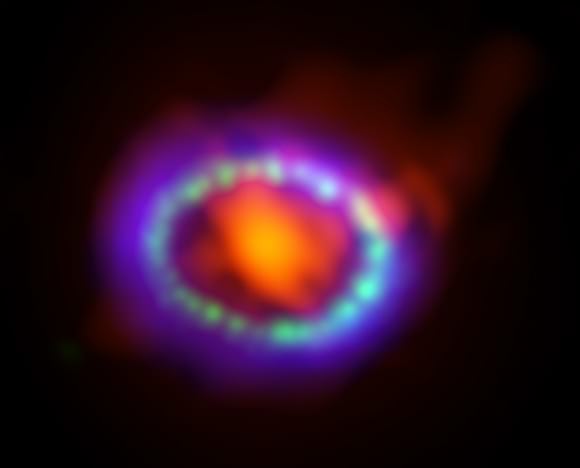

There are even a couple of really bright stars in the 8000 light year range, that we might just barely be able to see without a telescope. If a star detonates, we can see it much further away. The famous 1006 supernova was the brightest in history, recorded in China, Japan and the Middle East.

It was a total of 7,200 light years away and was visible in the daytime. There’s even large structures we can see. Outside the galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud is 160,000 light years and the Small Magellanic Cloud is almost 200,000 light years away. Unfortunately for us up North, these are only visible from Southern Hemisphere.The most distant thing we can see with our bare eyeballs is Andromeda at 2.6 million light years, which in dark skies looks like a fuzzy blob.

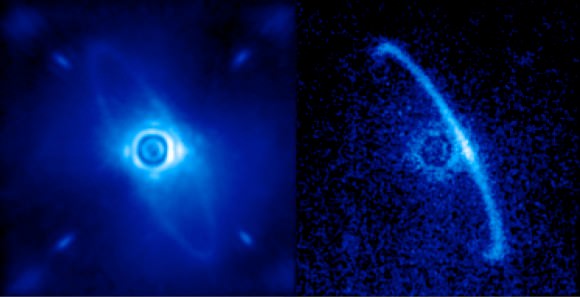

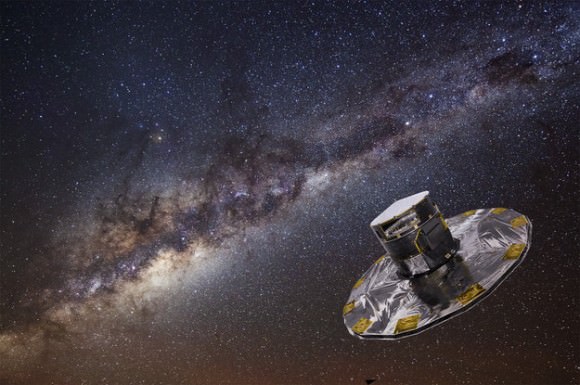

If we cheat and get a little help, say with binoculars – you can see magnitude 10 – fainter stars and galaxies at more than 10 million light-years away. With a telescope you can see much, much further. A regular 8-inch telescope would let you see the brightest quasars, more than 2 billion light years away. Using gravitational lensing the amazing Hubble space telescope can see galaxies, incredibly far out, where the light had left them just hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang.

If you could see in other wavelengths, you could see different distances. Fortunately for our precious radiation sensitive organs, Gamma and X rays are blocked by our atmosphere. But if you could see in that spectrum, you could see objects exploding billions of light years away. And if you could see in the radio spectrum, you’d be able to see the cosmic microwave background radiation, surrounding us in all directions and marking the edge of the observable universe.

Wouldn’t that be cool? Well, maybe we can… just a little. Turn on your television, some of the static on the screen is this very background radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang.

What do you think? If you could see far out in the Universe what would you like a close up view of? Tell us in the comments below.