[/caption]

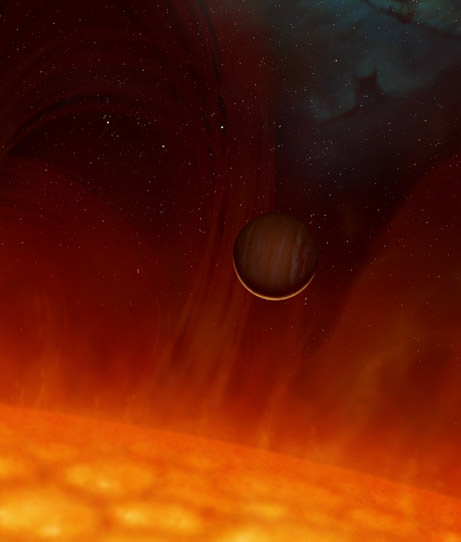

Amid all of the news last week regarding the discovery by Kepler of two Earth-sized planets orbiting another star, there was another similar find which hadn’t received as much attention. There were two more Earth-sized planets also just discovered by Kepler orbiting a different star. In this case, however, the star is an old and dying one, and has passed its red giant phase where it expands enormously, destroying (or at least barbecuing) any nearby planets in the process before becoming just an exposed core of its former self. The paper was just published in the journal Nature.

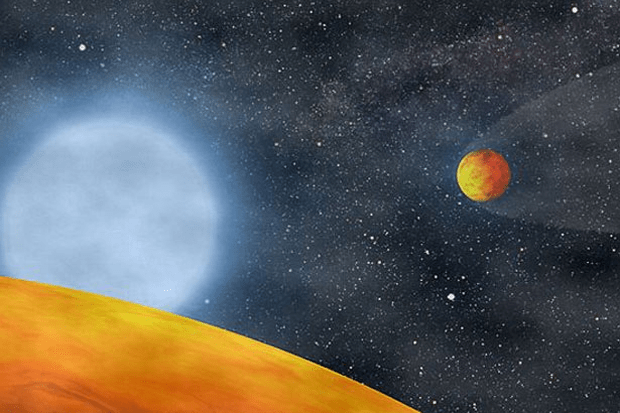

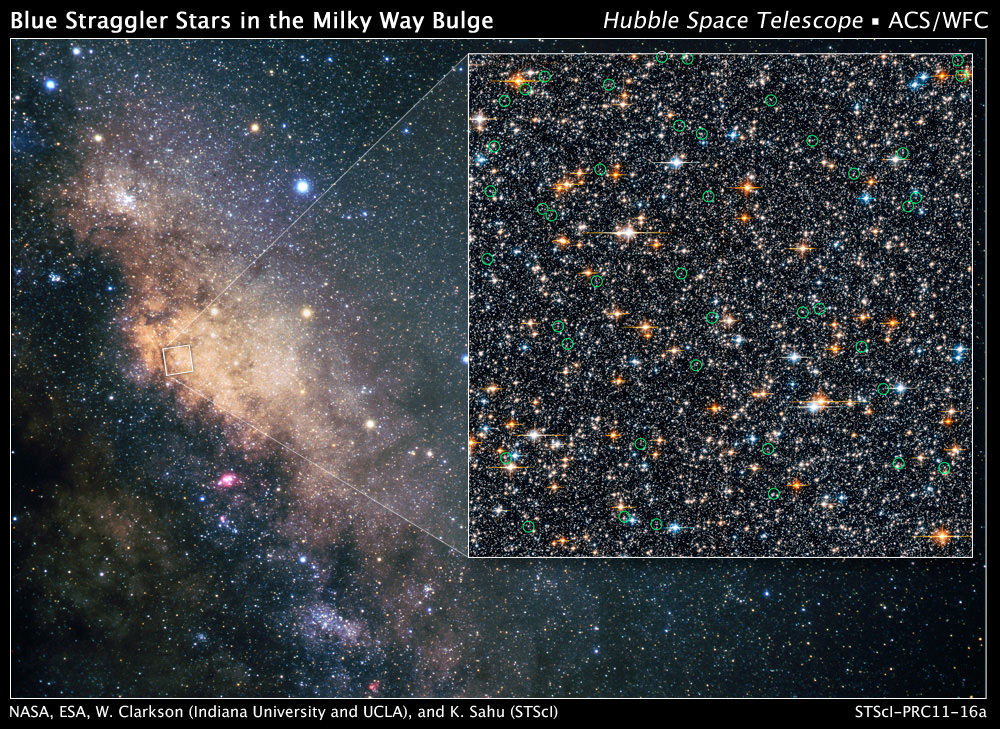

The two planets, KOI 55.01 and KOI 55.02, orbit the star KOI 55, a subdwarf B star, which is the leftover core of a red giant star. Both planets have very tight orbits close to the star, so they were probably engulfed during the red giant phase but managed to survive (albeit “deep-fried”). They are estimated to have radii of 0.76 and 0.87 that of Earth, the smallest known exoplanets found so far orbiting an active star.

According to lead author Stephane Charpinet, “Having migrated so close, they probably plunged deep into the star’s envelope during the red giant phase, but survived.”

“As the star puffs up and engulfs the planet, the planet has to plow through the star’s hot atmosphere and that causes friction, sending it spiraling toward the star,” added Elizabeth ‘Betsy’ Green, an associate astronomer at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory. “As it’s doing that, it helps strip atmosphere off the star. At the same time, the friction with the star’s envelope also strips the gaseous and liquid layers off the planet, leaving behind only some part of the solid core, scorched but still there.”

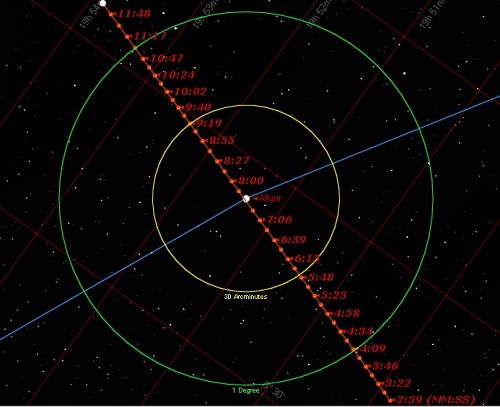

The discovery was also unexpected; the star had already been the subject of study using the telescopes at Kitt Peak National Observatory, part of a project to examine pulsating stars. For more accurate measurements however, the team used data from the orbiting Kepler space telescope which is free of interfering atmospheric effects. According to Green, “I had already obtained excellent high-signal to noise spectra of the hot subdwarf B star KOI 55 with our telescopes on Kitt Peak, before Kepler was even launched. Once Kepler was in orbit and began finding all these pulsational modes, my co-authors at the University of Toulouse and the University of Montreal were able to analyze this star immediately using their state-of-the art computer models.”

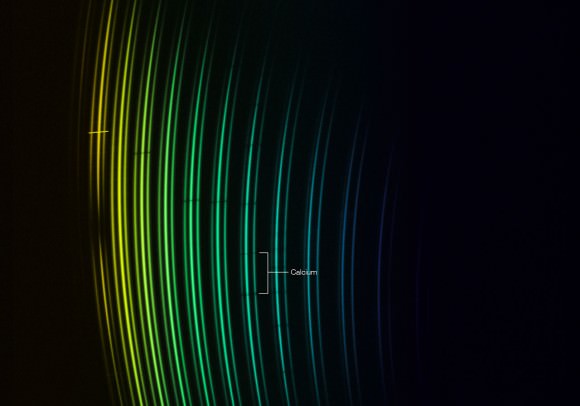

Two tiny modulations in the pulsations of the star were found, which further analysis indicated could only come from planets passing in front of the star (from our viewpoint) every 5.76 and 8.23 hours.

Our own Sun awaits a similar fate billions of years from now and is expected to swallow Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars during its expansion phase. “When our sun swells up to become a red giant, it will engulf the Earth,” said Green. “If a tiny planet like the Earth spends 1 billion years in an environment like that, it will just evaporate. Only planets with masses very much larger than the Earth, like Jupiter or Saturn, could possibly survive.” The discovery should help scientists to better understand the destiny of planetary systems including our own.

This finding is important in that it not only confirms that Earth-size planets are out there, and are probably common, but that they and other planets (of a wide variety so far) are being found orbiting different types of stars, from newly born ones, to middle-age ones and even dying stars (or dead in the case of pulsars). They are a natural product of star formation which of course has implications in the search for life elsewhere.

The abstract of the paper is here, but downloading the full article requires a single-article payment of $32.00 US or a subscription to Nature.