[/caption]

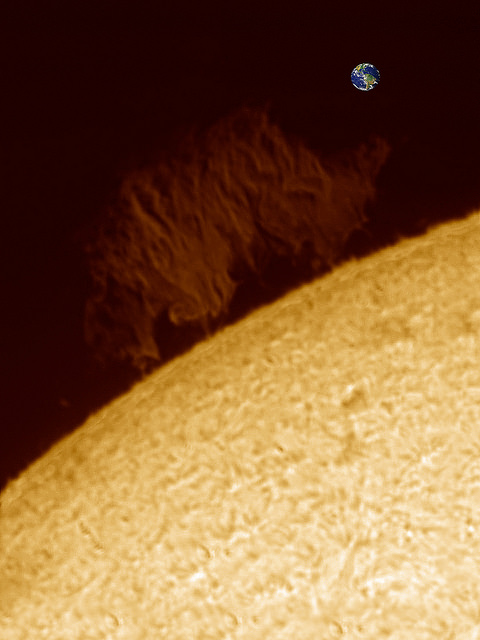

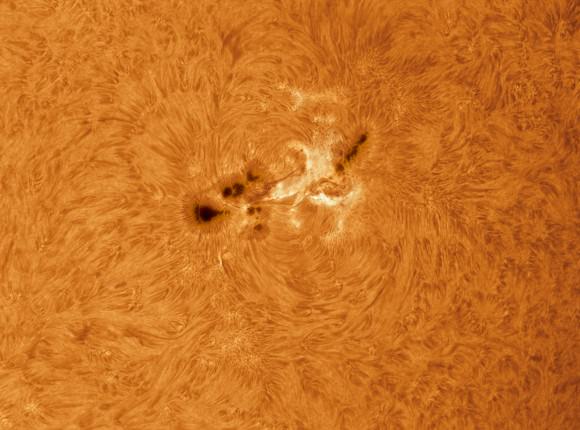

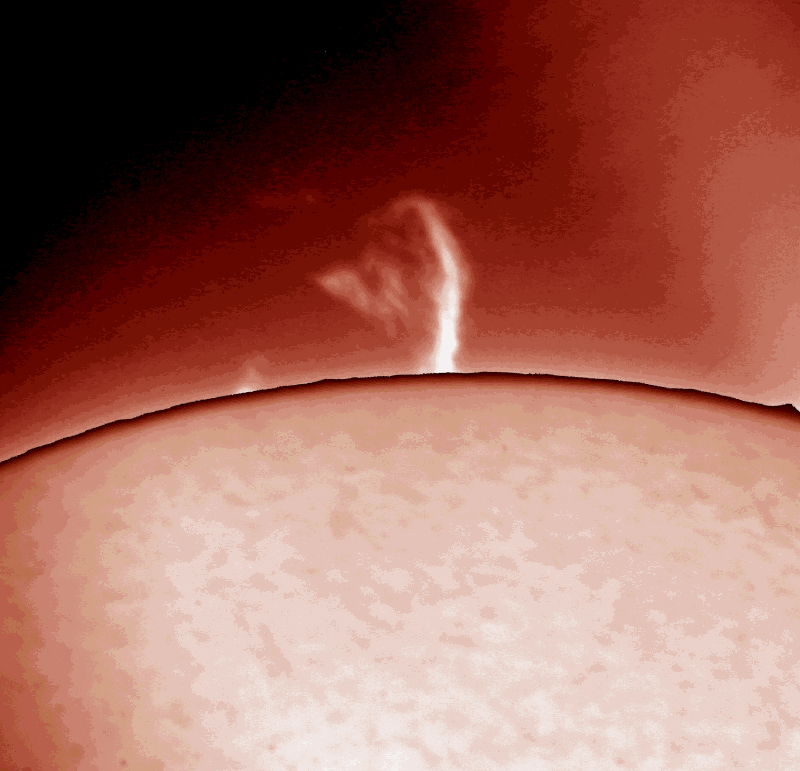

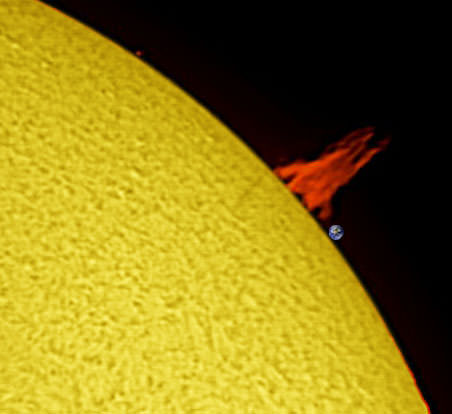

A huge wall of plasma rose from the Sun’s southeast limb over the weekend, with what might be one of the biggest prominences seen in many years. César Cantu from Monterrey, Mexico, took the image above, adding an “Earth” for reference of how big this prominence really is. A solar prominence is a large, bright feature extending outward from the Sun’s surface. Prominences are anchored to the Sun’s surface in the photosphere, and can loop hundreds of thousands of kilometers into space.

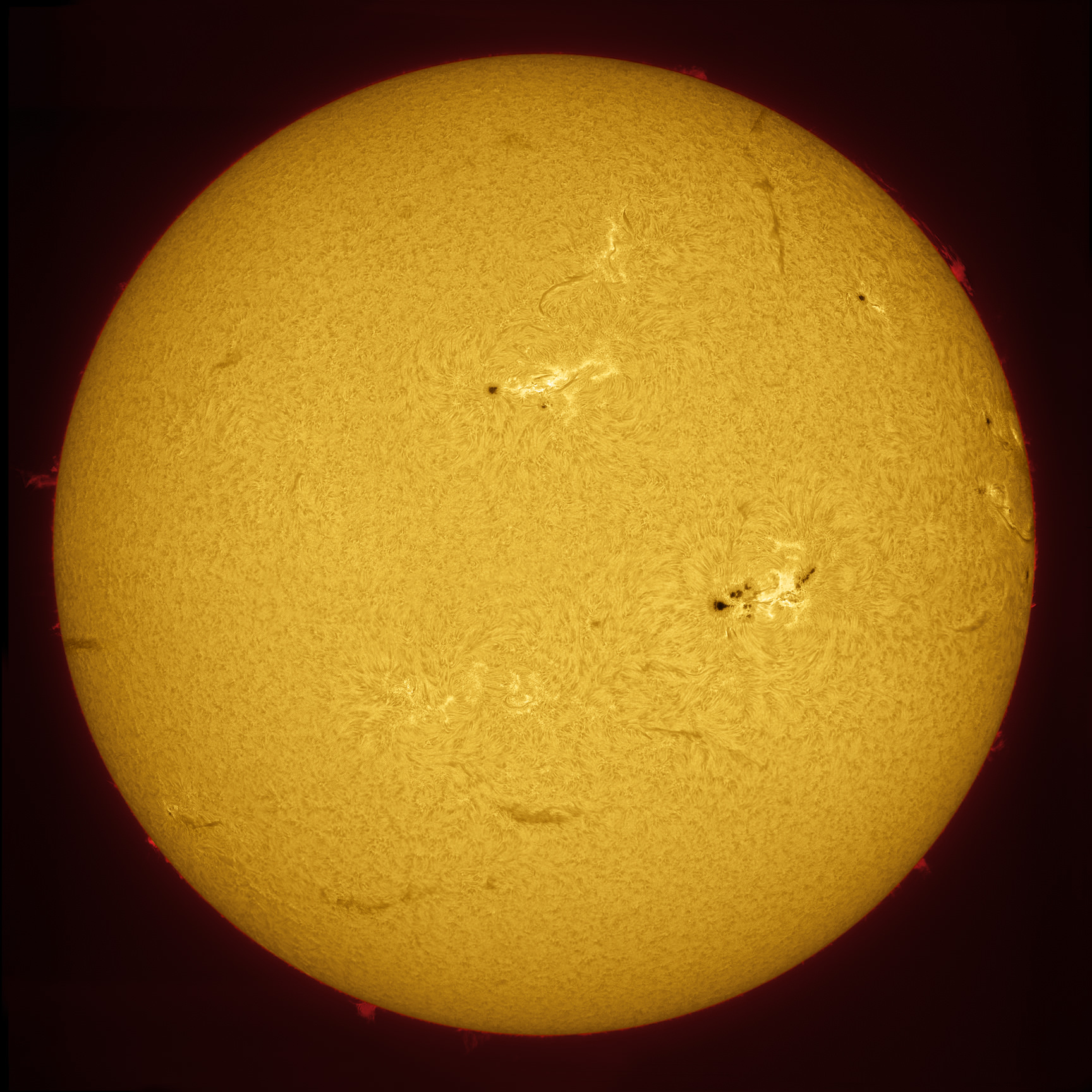

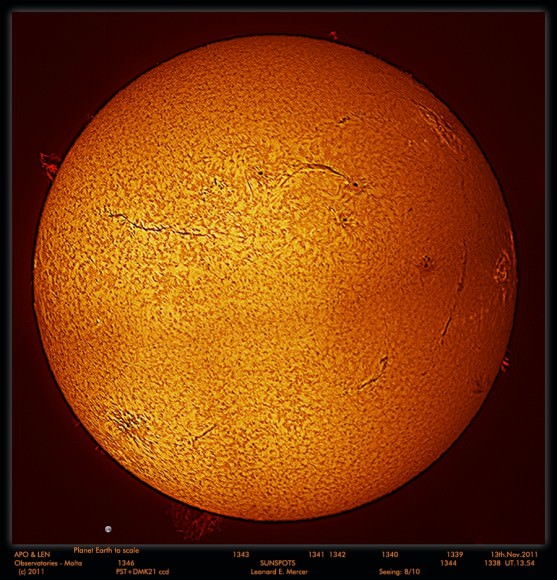

Leonard Mercer from Malta sent us the image below, saying “I never encountered such a huge prominence since I started imaging the Sun.”

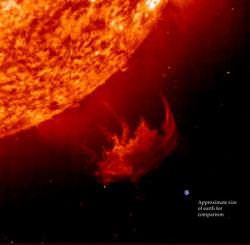

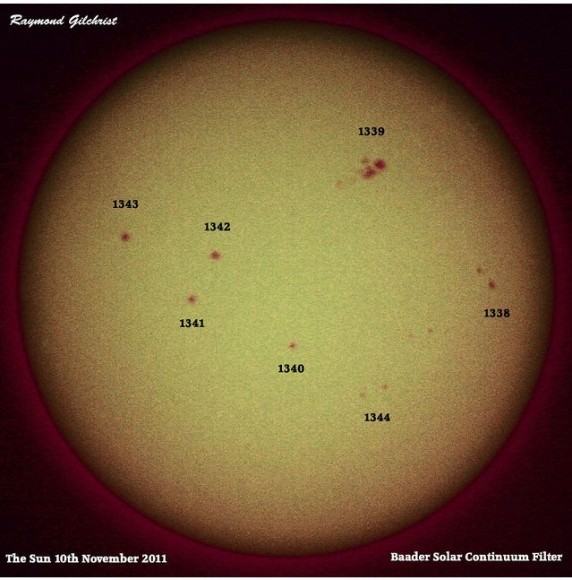

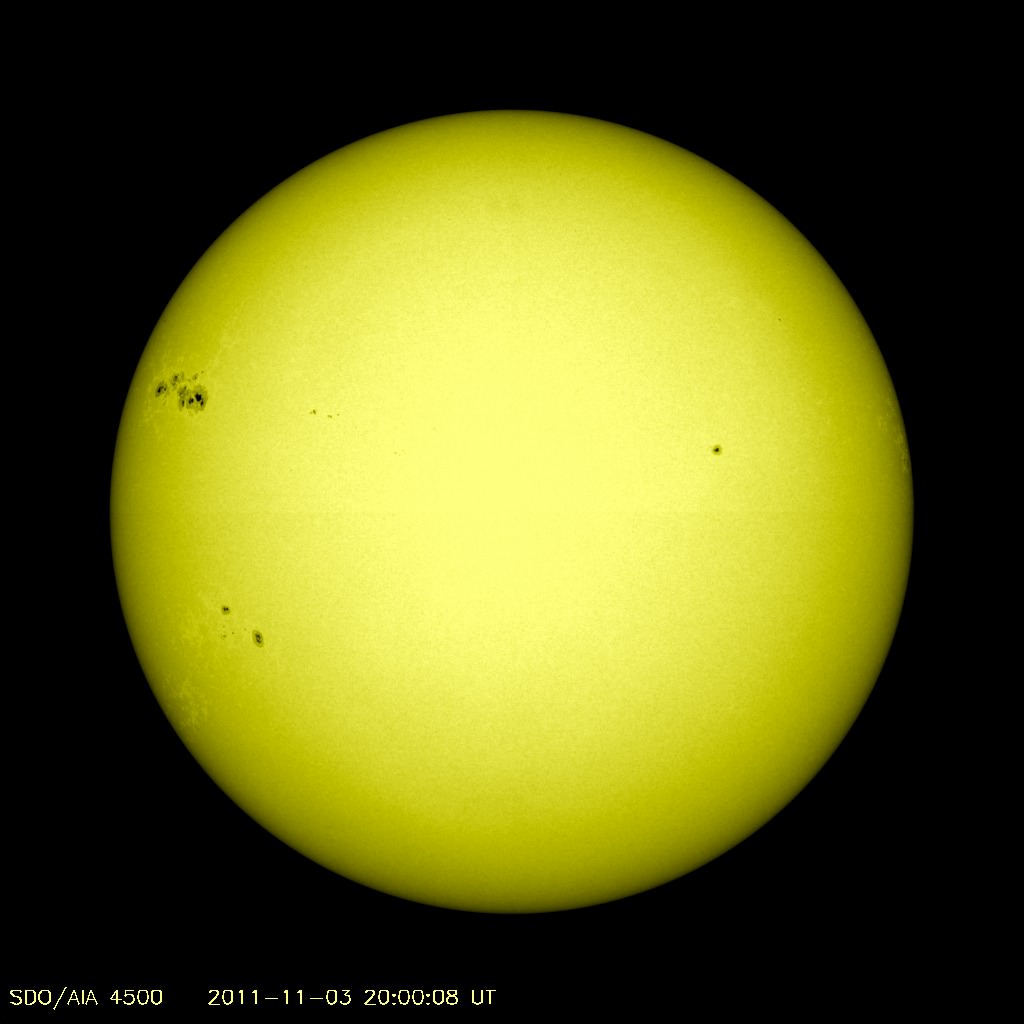

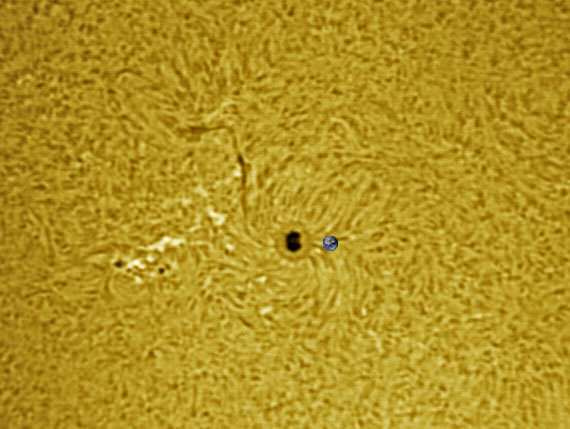

As large as this prominence is, there was also another even larger feature on the Sun. A filament (which is a prominence that is viewed against the solar disk) on the upper left snakes across the Sun’s surface, stretching more than a million km or about three times the distance between Earth and the Moon.

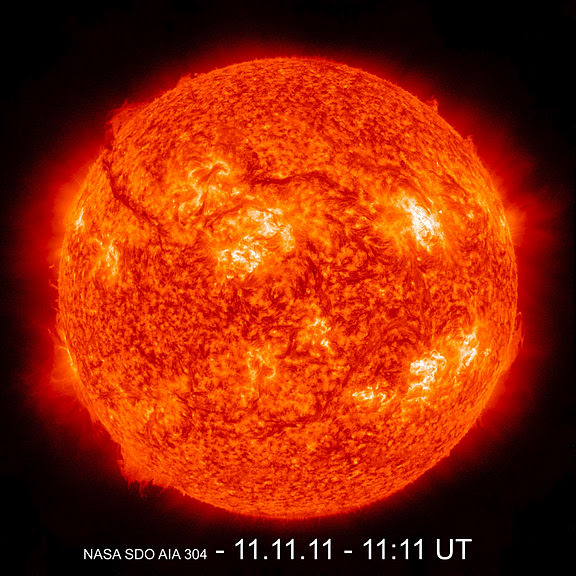

The video below from the Solar Dynamics Observatory shows the filament intact at first, and then later, from 13:00 to 16:00 UT on November 14, 2011, the filament shoots up from the Sun’s surface and snaps apart.

The SDO team explains that the red-glowing looped material is plasma, a hot gas comprised of electrically charged hydrogen and helium. The prominence plasma flows along a tangled and twisted structure of magnetic fields generated by the Sun’s internal dynamo. An erupting prominence occurs when such a structure becomes unstable and bursts outward, releasing the plasma.

Despite all this activity, there hasn’t been much as far as solar flares, but Spaceweather.com encourages anyone with solar telescopes to monitor developments.