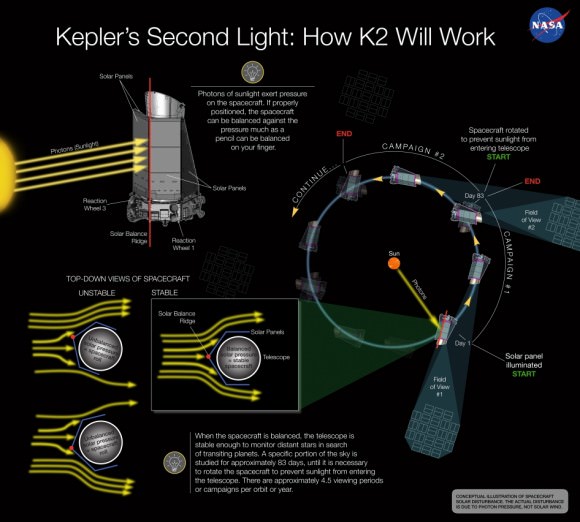

It’s alive! NASA’s Kepler space telescope had to stop planet-hunting during Earth’s northern-hemisphere summer 2013 when a second of its four pointing devices (reaction wheels) failed. But using a new technique that takes advantage of the solar wind, Kepler has found its first exoplanet since the K2 mission was publicly proposed in November 2013.

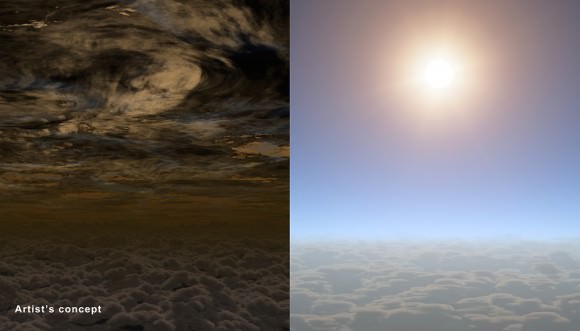

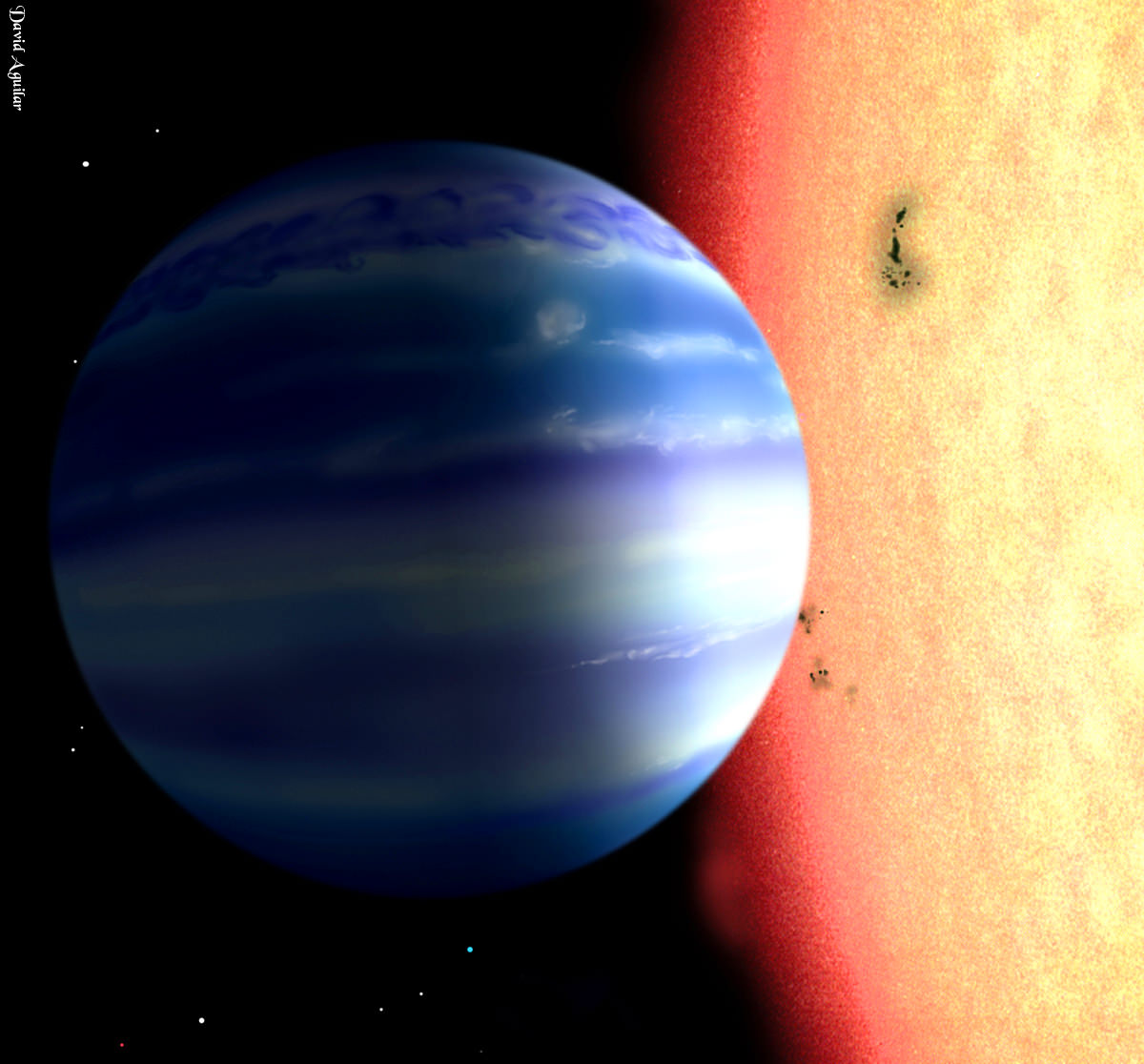

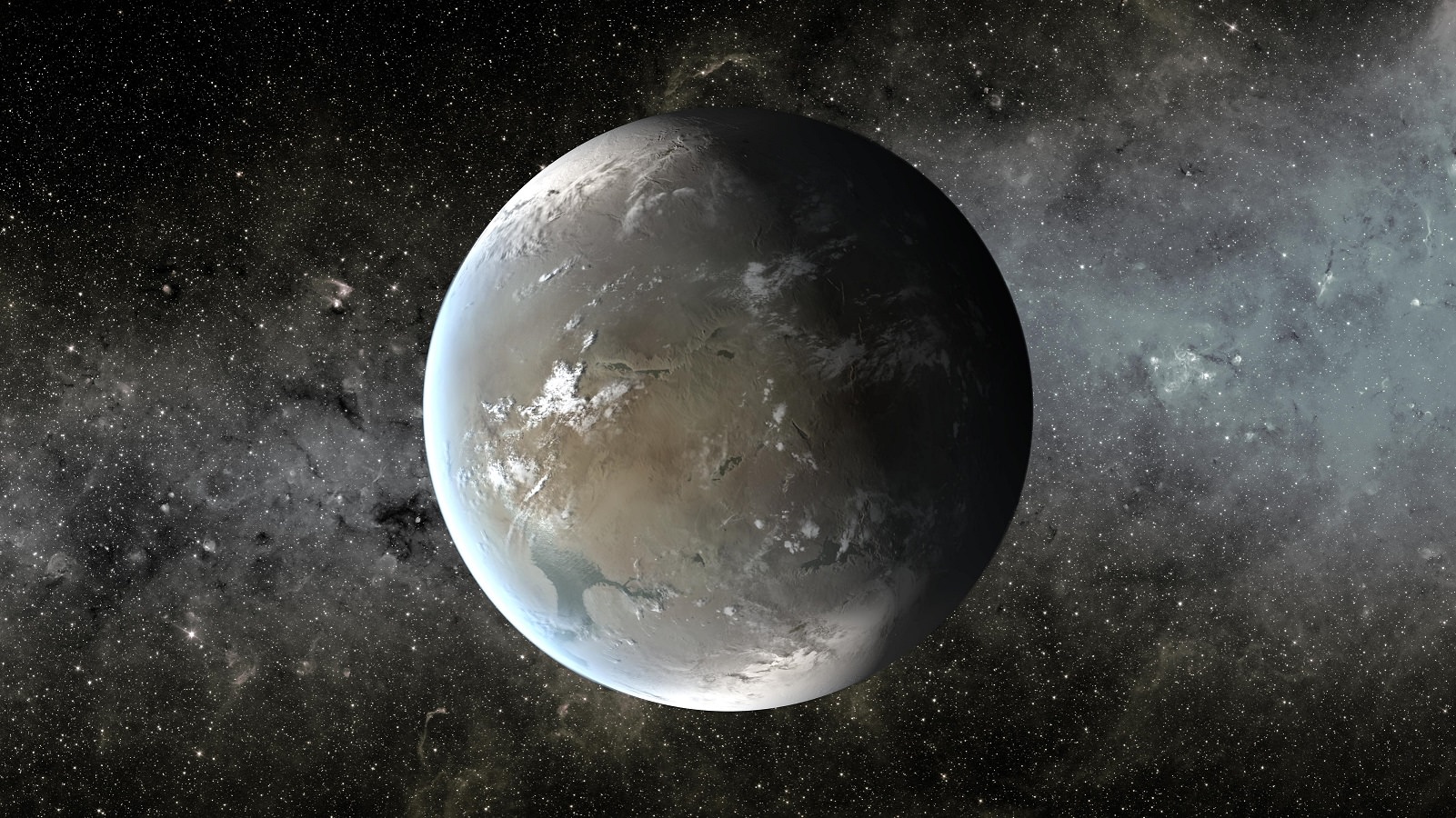

And despite a loss of pointing precision, Kepler’s find was a smaller planet — a super-Earth! It’s likely a water world or a rocky core shrouded in a thick, Neptune-like atmosphere. Called HIP 116454b, it’s 2.5 times the size of Earth and a whopping 12 times the mass. It circles its dwarf star quickly, every 9.1 days, and is about 180 light-years from Earth.

“Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, Kepler has been reborn and is continuing to make discoveries. Even better, the planet it found is ripe for follow-up studies,” stated lead author Andrew Vanderburg of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

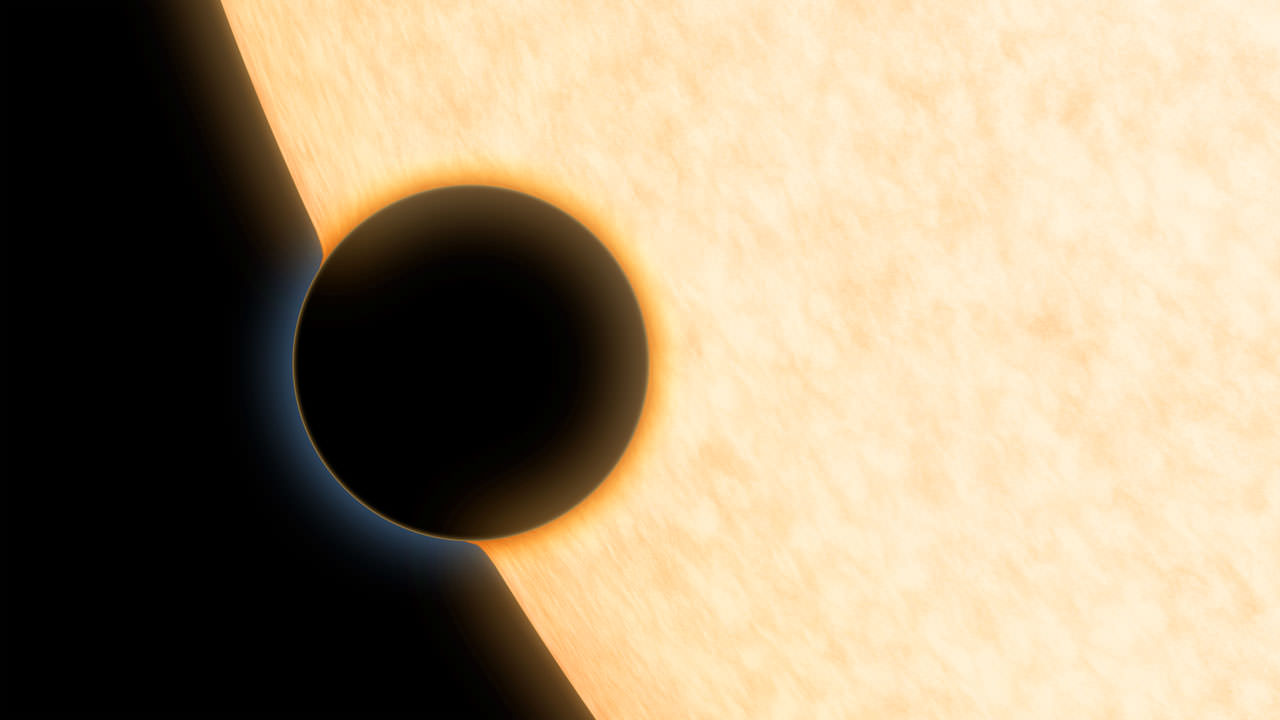

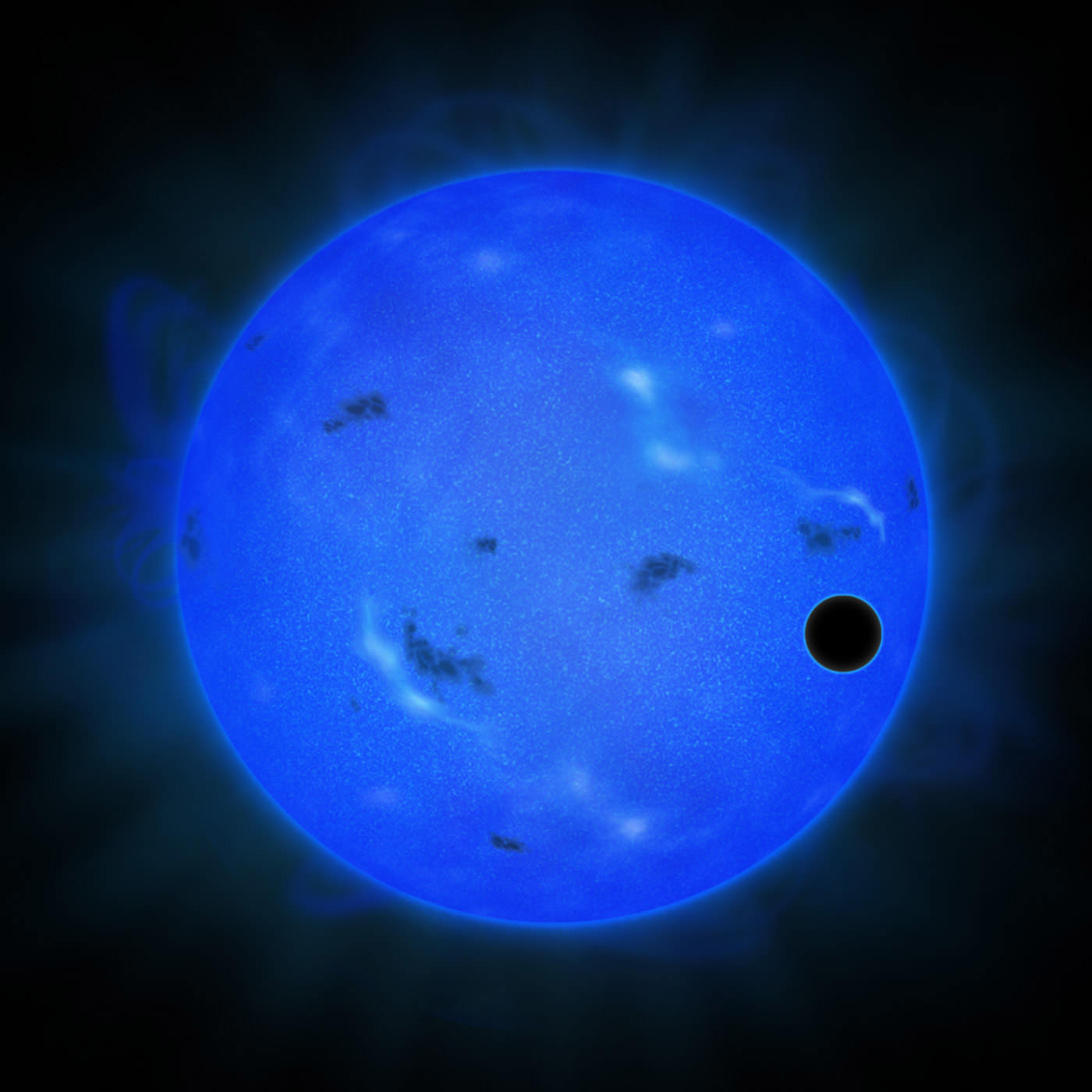

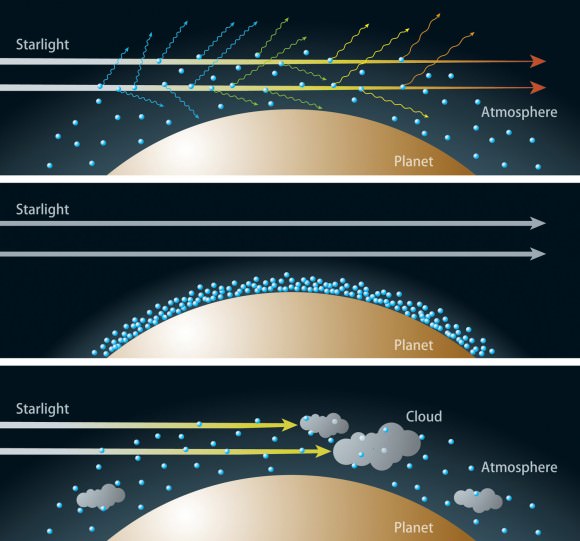

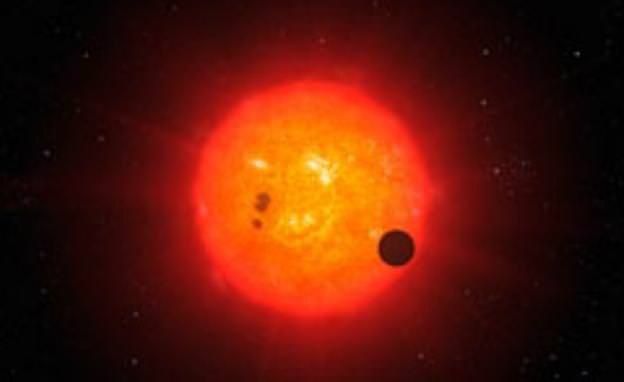

Kepler ferrets out exoplanets from their parent stars while watching for transits — when a world passes across the face of its parent sun. This is easiest to find on huge planets that are orbiting dim stars, such as red dwarfs. The smaller the planet and/or brighter the star, the more difficult it is to view the tiny shadow.

The telescope needs at least three reaction wheels to point consistently in space, which it did for four years, gazing at the Cygnus constellation. (And there’s still a lot of data to come from that mission, including the follow-up to a bonanza where Kepler detected hundreds of new exoplanets using a new technique for multiple-planet systems.)

But now, Kepler needs an extra hand to do so. Without a mechanic handy to send out to telescope’s orbit around the Sun, scientists decided instead to use sunlight pressure as a sort of “virtual” reaction wheel. The K2 mission underwent several tests and was approved budgetarily in May, through 2016.

The drawback is Kepler needs to change positions every 83 days since the Sun eventually gets in the telescope’s viewfinder; also, there are losses in precision compared to the original mission. The benefit is it can also observe objects such as supernovae and star clusters.

“Due to Kepler’s reduced pointing capabilities, extracting useful data requires sophisticated computer analysis,” CFA added in a statement. “Vanderburg and his colleagues developed specialized software to correct for spacecraft movements, achieving about half the photometric precision of the original Kepler mission.”

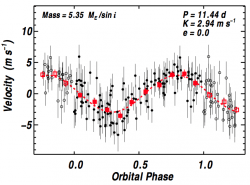

That said, the first nine-day test with K2 yielded one planetary transit that was confirmed with measurements of the star’s “wobble” as the planet tugged on it, using the HARPS-North spectrograph on the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo in the Canary Islands. A small Canadian satellite called MOST (Microvariability and Oscillations of STars) also found transits, albeit weakly.

A paper based on the research will appear in the Astrophysical Journal.