Our universe contains some enormous black holes. The supermassive black hole in the center of our galaxy has a mass of 4 million Suns, but it’s rather small as galactic black holes go. Many galactic black holes have a billion solar masses, and the most massive known black hole is estimated to have a mass of nearly 70 billion Suns. But just how big can a black hole get?

Continue reading “In Theory, Supermassive Black Holes Could get Even More Supermassive”Missing: Supermassive Black Hole With up to 100 BILLION Times the Mass of the Sun

The massive galaxy cluster Abell 2261 should have a supermassive black hole in its center. But it doesn’t. Astronomers have looked everywhere – even between the couch cushions. What’s going on?

Continue reading “Missing: Supermassive Black Hole With up to 100 BILLION Times the Mass of the Sun”Some Quasars Actually Contain Two Supermassive Black Holes in the Process of Merging

Quasars are some of the most powerful objects in the Universe. They were first discovered in the 1950s as bright radio sources coming from almost point-like objects. They were given the name quasi-stellar radio sources, or quasars for short. We now know that they are powered by supermassive black holes at the center of distant galaxies.

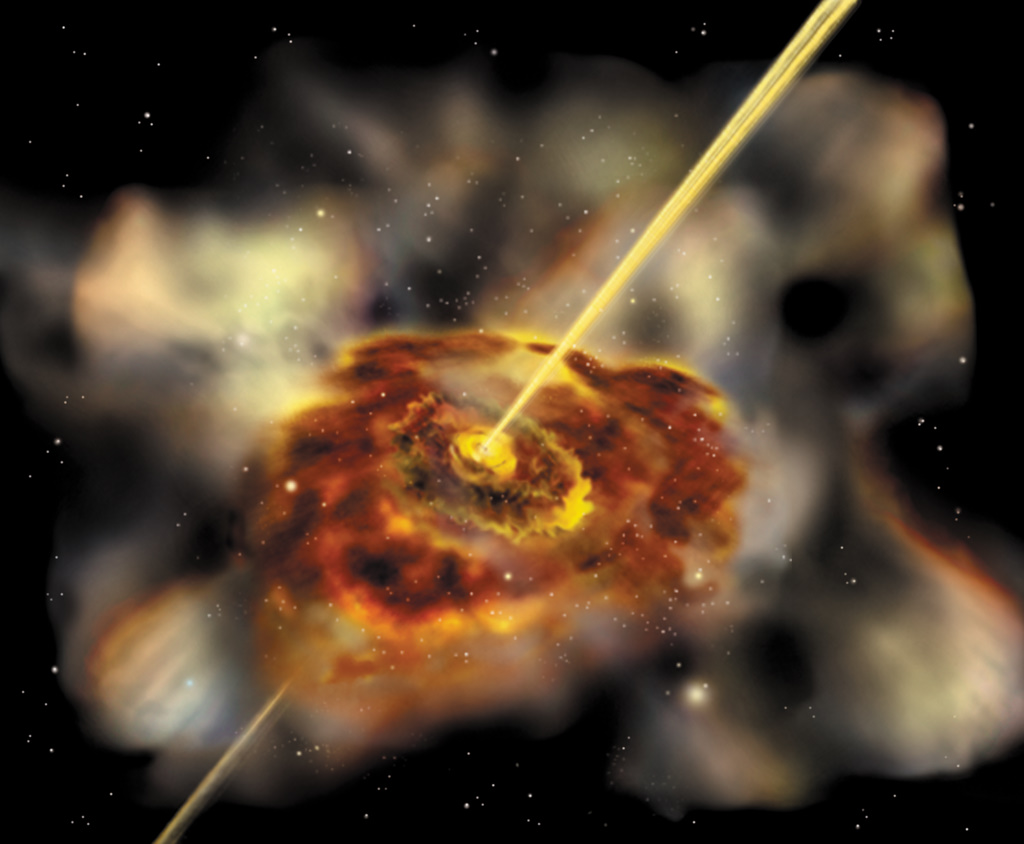

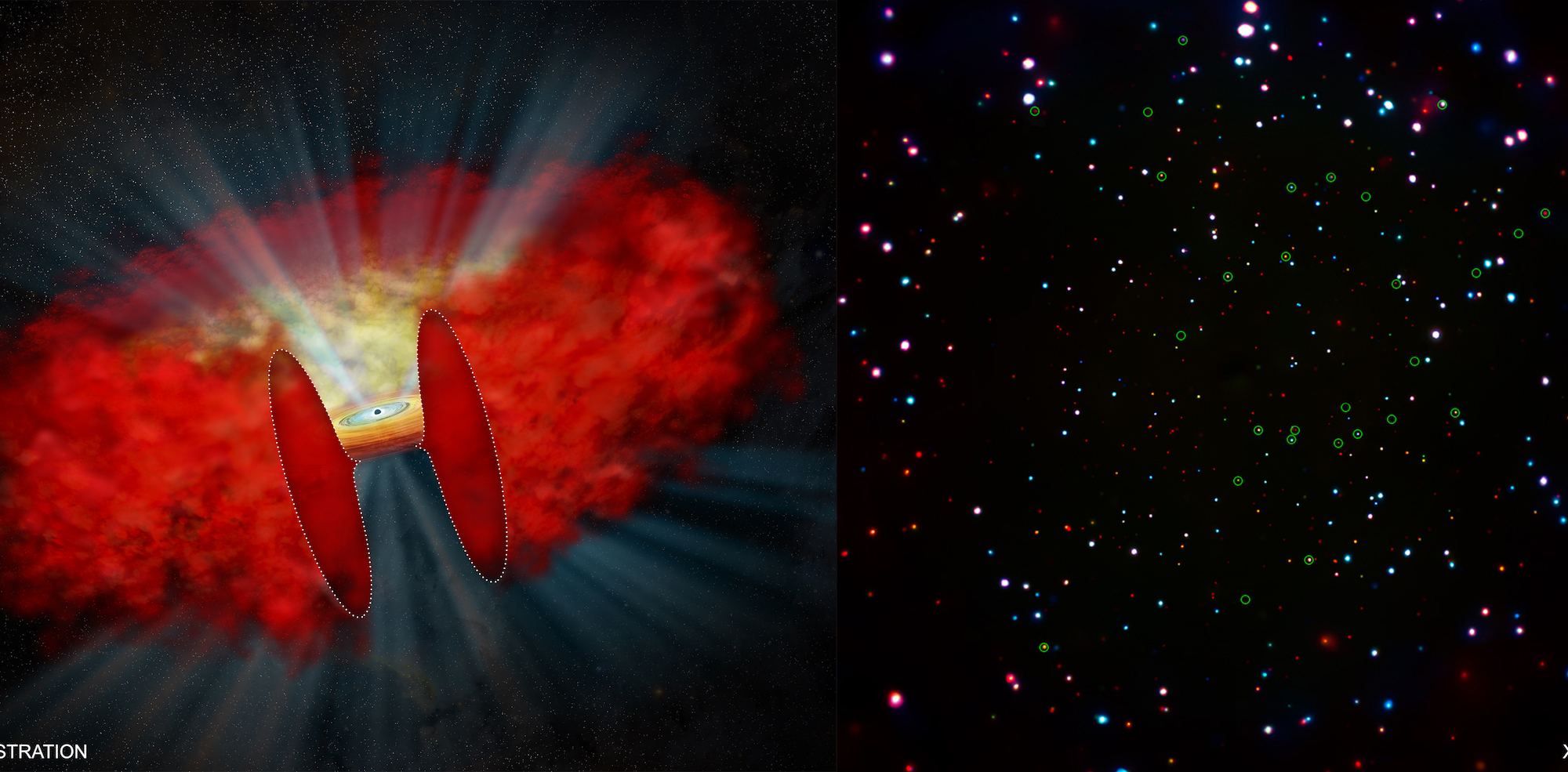

Continue reading “Some Quasars Actually Contain Two Supermassive Black Holes in the Process of Merging”Supermassive black holes can cloak themselves in a cocoon of dust, making them invisible even when they should be bright quasars

Quasars are the most powerful sources of light in the universe, but sometimes they’re hard to find. A team of astronomers used the Chandra X-ray Space Telescope to find some diamonds in the rough.

Continue reading “Supermassive black holes can cloak themselves in a cocoon of dust, making them invisible even when they should be bright quasars”There’s a Black Hole With 34 Billion Times the Mass of the Sun, Eating Roughly a Star Every Day

In the 1960s, astronomers began theorizing that there might be black holes in the Universe that are so massive – supermassive black holes (SMBHs) – they could power the nuclei of active galaxies (aka. quasars). A decade later, astronomers discovered that an SMBH existed at the center of the Milky Way (Sagittarius A*); and by the 1990s, it became clear that most large galaxies in the Universe are likely to have one.

Since that time, astronomers have been hunting for the largest SMBH they can find in the hopes that they can see just how massive these things can get! And thanks to new research led by astronomers from the Australian National University, the latest undisputed heavy-weight contender has been found! With roughly 34 billion times the mass of our Sun, this SMBH (J2157) is the fastest-growing black hole and largest quasar observed to date.

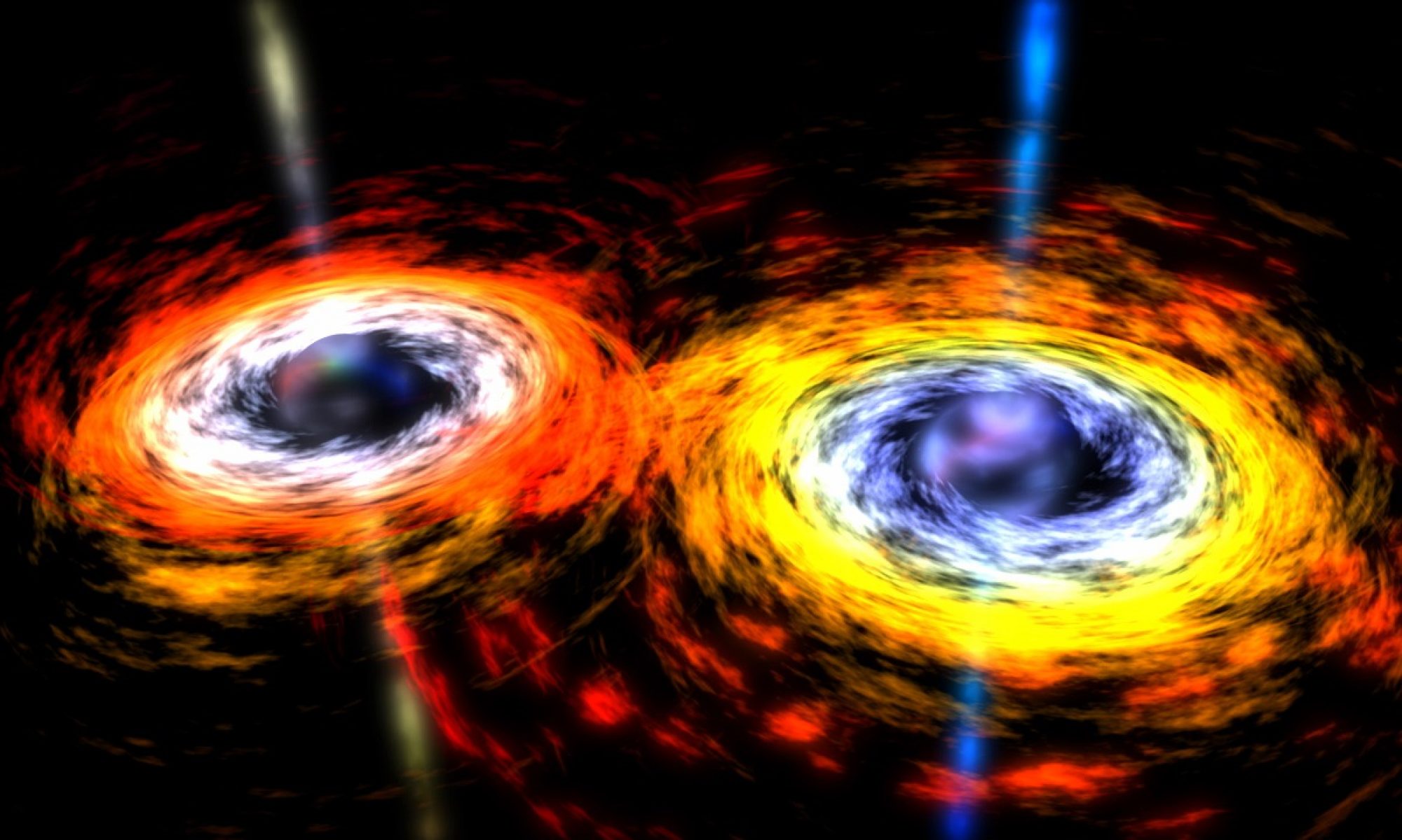

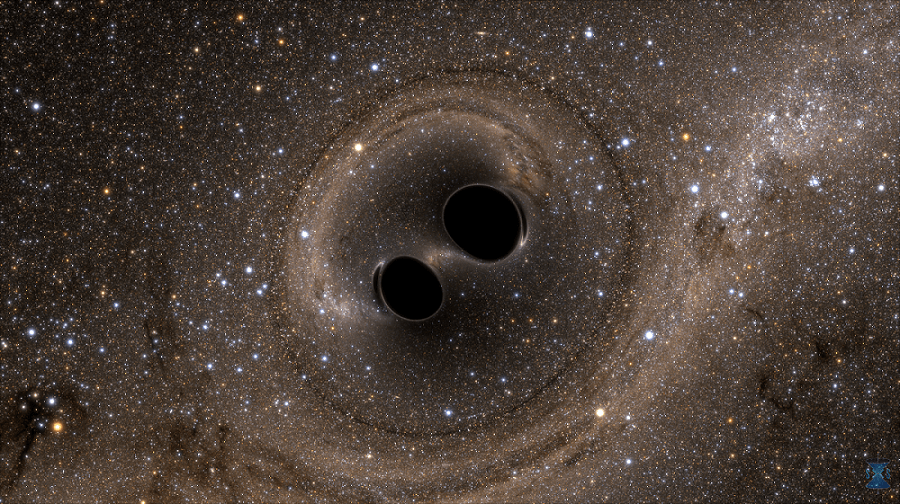

Continue reading “There’s a Black Hole With 34 Billion Times the Mass of the Sun, Eating Roughly a Star Every Day”It might just be possible to see a light flash too when black holes merge

Black hole merger events are some of the most energetic, fearsomely energetic events in all the cosmos. When black holes merge, they’re entirely invisible, the only evidence of the cataclysm some faint whisper of gravitational waves. Until now.

Continue reading “It might just be possible to see a light flash too when black holes merge”New Simulations Show How Black Holes Grow, Through Mergers and Accretion

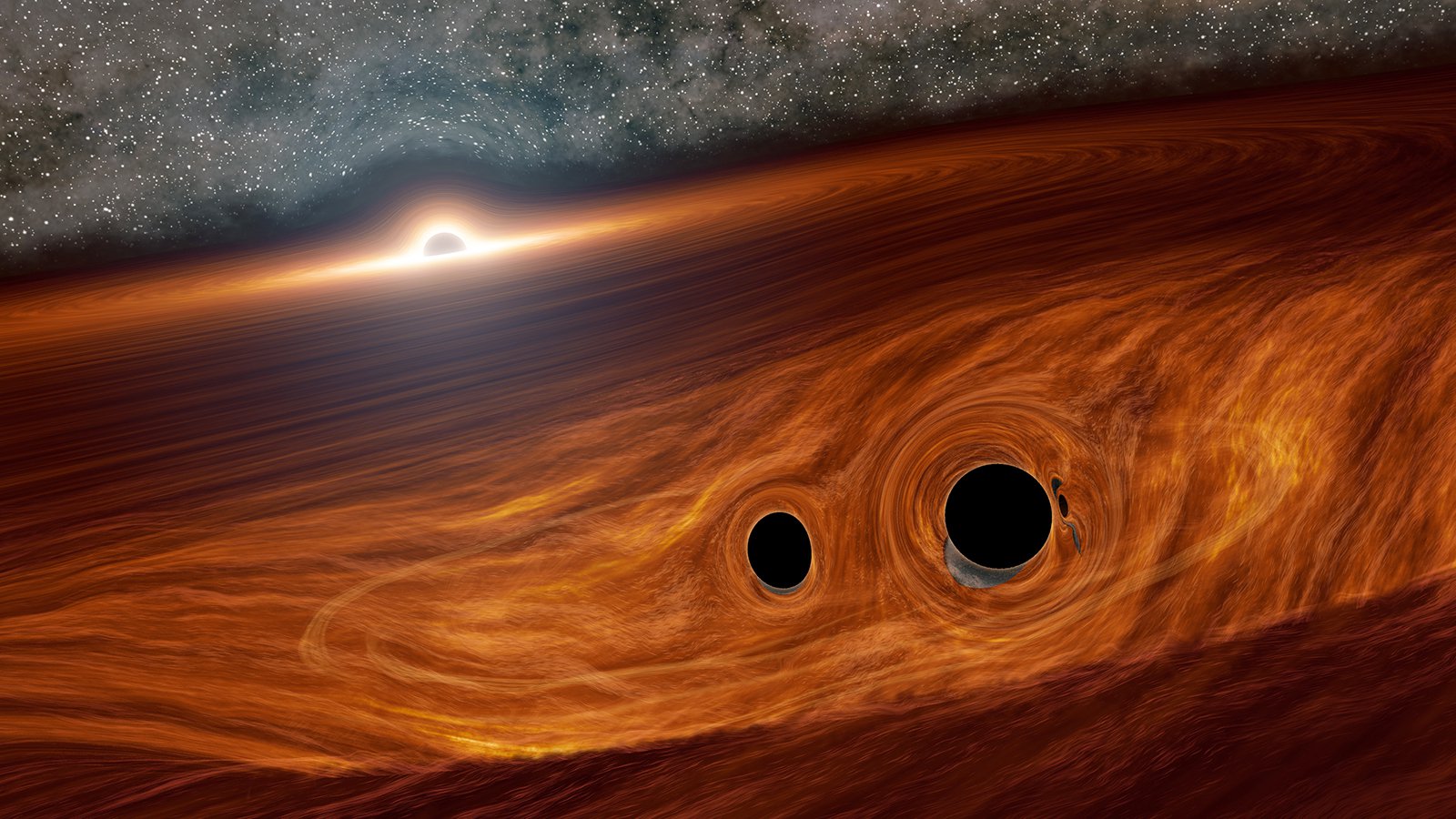

One of the most pressing questions in astronomy concerns black holes. We know that massive stars that explode as supernovae can leave stellar mass black holes as remnants. And astrophysicists understand that process. But what about the supermassive black holes (SMBHs) like Sagittarius A-star (Sgr A*,) at the heart of the Milky Way?

SMBHs can have a billion solar masses. How do they get so big?

Continue reading “New Simulations Show How Black Holes Grow, Through Mergers and Accretion”This Galaxy is the Very Definition of “Flocculent”

I know you’re Googling “flocculent” right now, unless you happen to be a chemist, or maybe a home brewer.

You could spend each day of your life staring at a different galaxy, and you’d never even come remotely close to seeing even a tiny percentage of all the galaxies in the Universe. Of course, nobody knows for sure exactly how many galaxies there are. But there might be up to two trillion of them. If you live to be a hundred, that’s only 36,500 galaxies that you’d look at. Puts things in perspective.

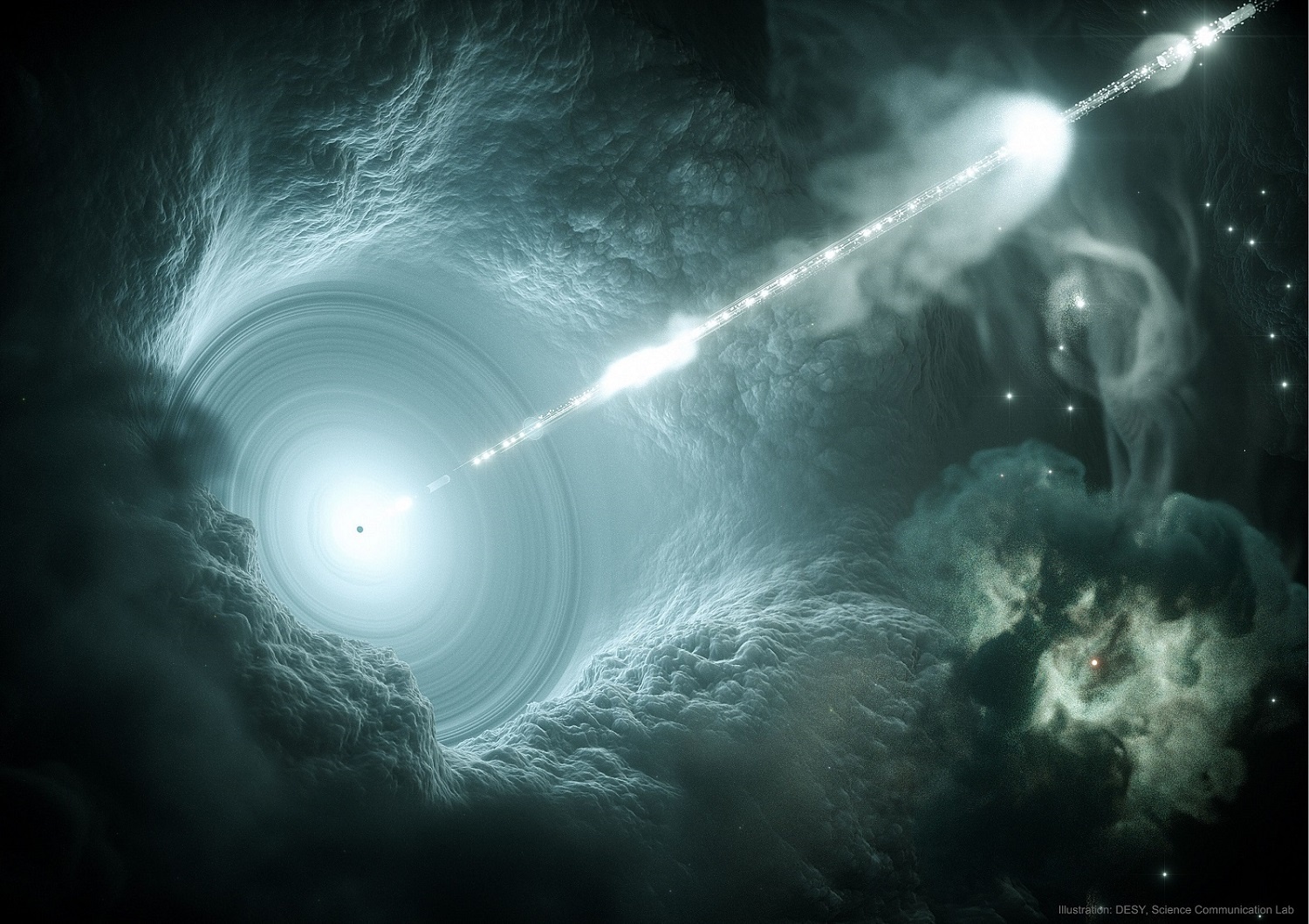

Continue reading “This Galaxy is the Very Definition of “Flocculent””Blazar Found Blazing When the Universe was Only a Billion Years Old

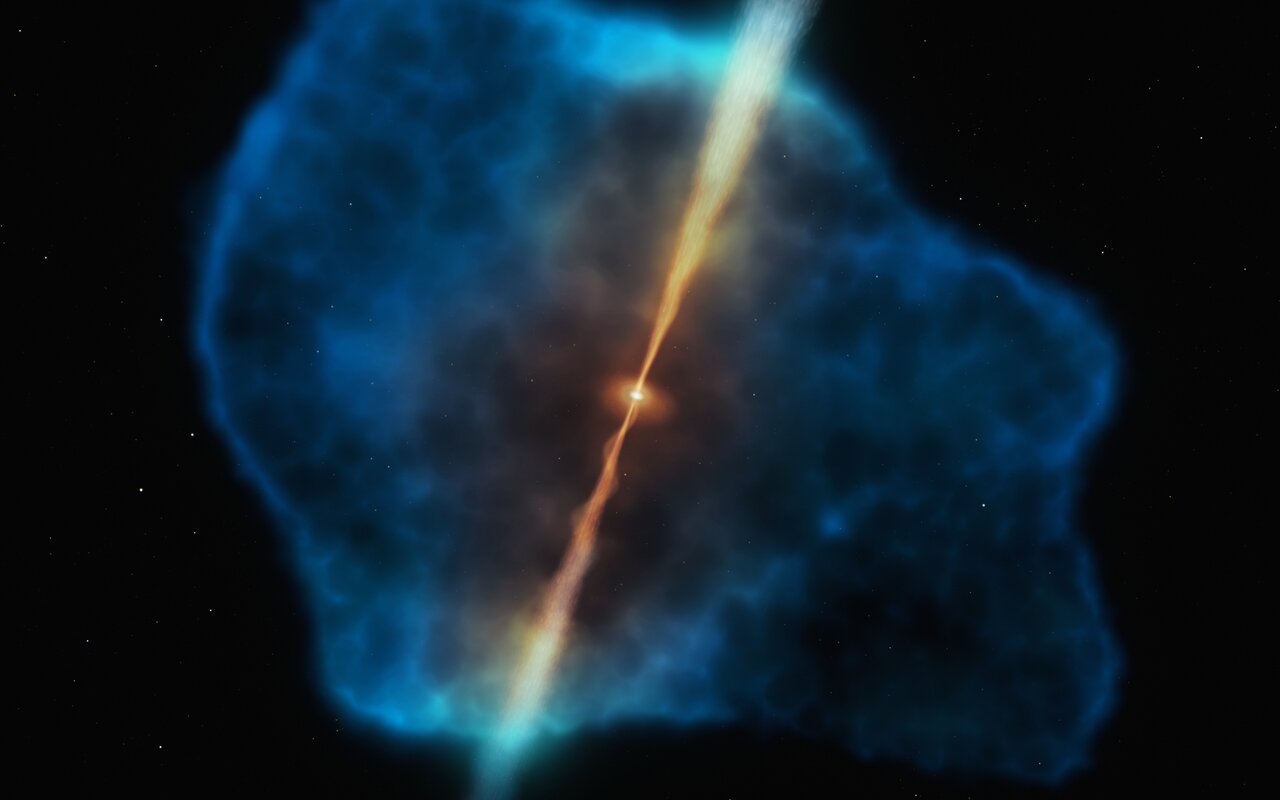

Since the 1950s, astronomers have known of galaxies that have particularly bright centers – aka. Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs) or quasars. This luminosity is the result of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at their centers consuming matter and releasing electromagnetic energy. Further studies revealed that there are some quasars that appear particularly bright because their relativistic jets are directed towards Earth.

In 1978, astronomer Edward Speigel coined the term “blazar” to describe this particular class of object. Using the telescopes at the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory (LBTO) in Arizona, a research team recently observed a blazar located 13 billion light-years from Earth. This object, designated PSO J030947.49+271757.31 (or PSO J0309+27), is the most distant blazar ever observed and foretells the existence of many more!

Continue reading “Blazar Found Blazing When the Universe was Only a Billion Years Old”Black Holes Were Already Feasting Just 1.5 Billion Years After the Big Bang

Thanks to the vastly improved capabilities of today’s telescopes, astronomers have been probing deeper into the cosmos and further back in time. In so doing, they have been able to address some long-standing mysteries about how the Universe evolved since the Big Bang. One of these mysteries is how supermassive black holes (SMBHs), which play a crucial role in the evolution of galaxies, formed during the early Universe.

Using the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, an international team of astronomers observed galaxies as they appeared about 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang (ca. 12.5 billion years ago). Surprisingly, they observed large reservoirs of cool hydrogen gas that could have provided a sufficient “food source” for SMBHs. These results could explain how SMBHs grew so fast during the period known as the Cosmic Dawn.

Continue reading “Black Holes Were Already Feasting Just 1.5 Billion Years After the Big Bang”