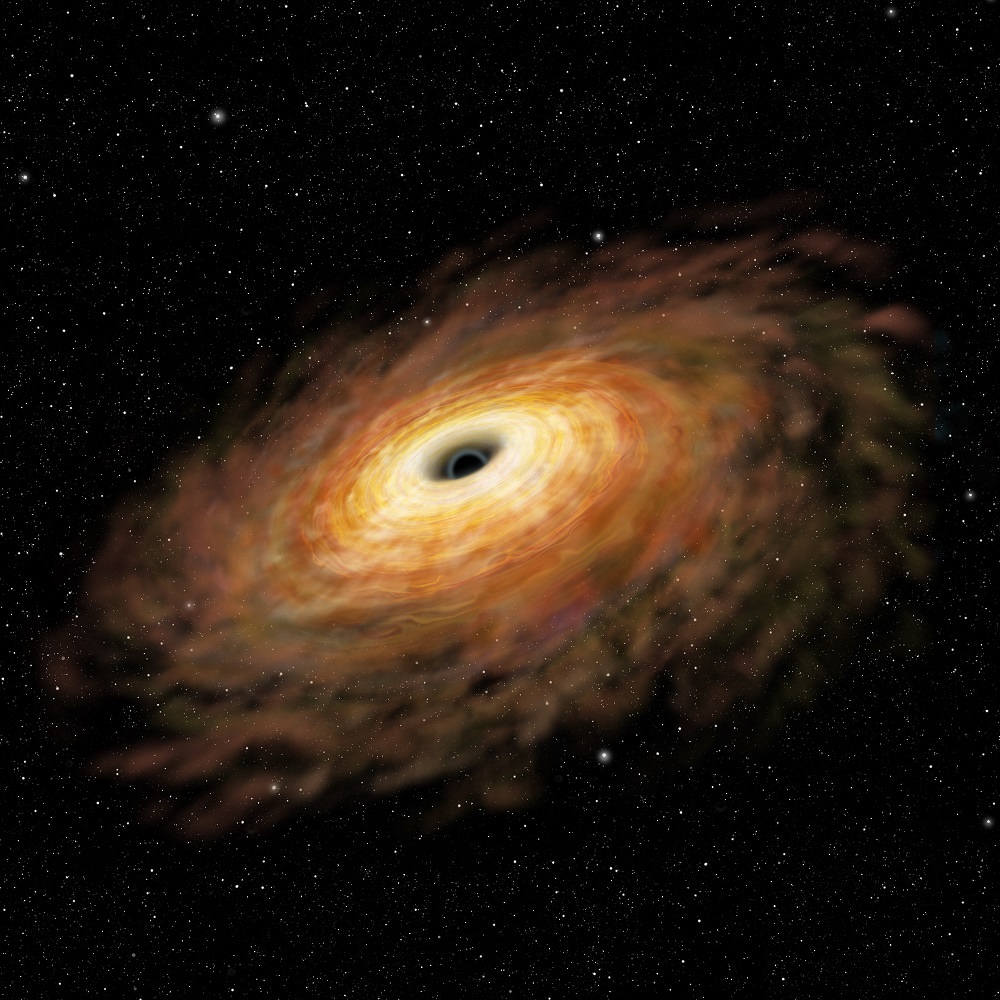

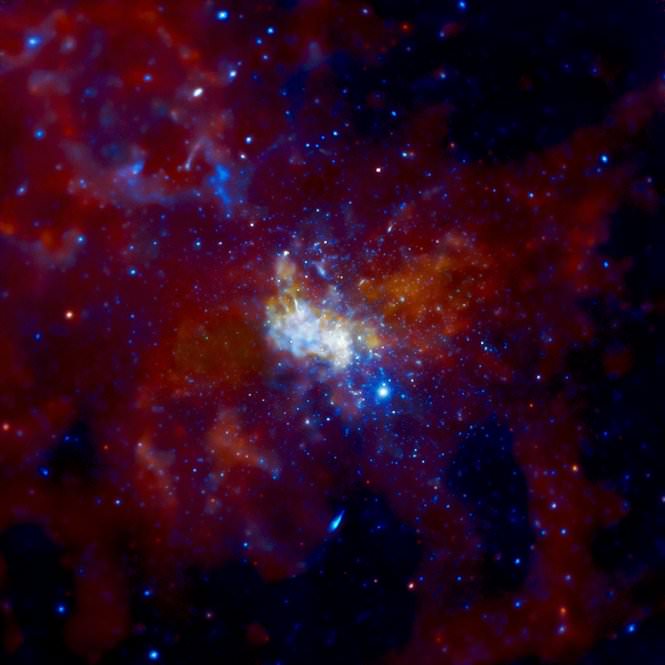

NASA’s Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) has captured a spectacular event: a supermassive black hole’s gravity tugging on nearby X-ray light.

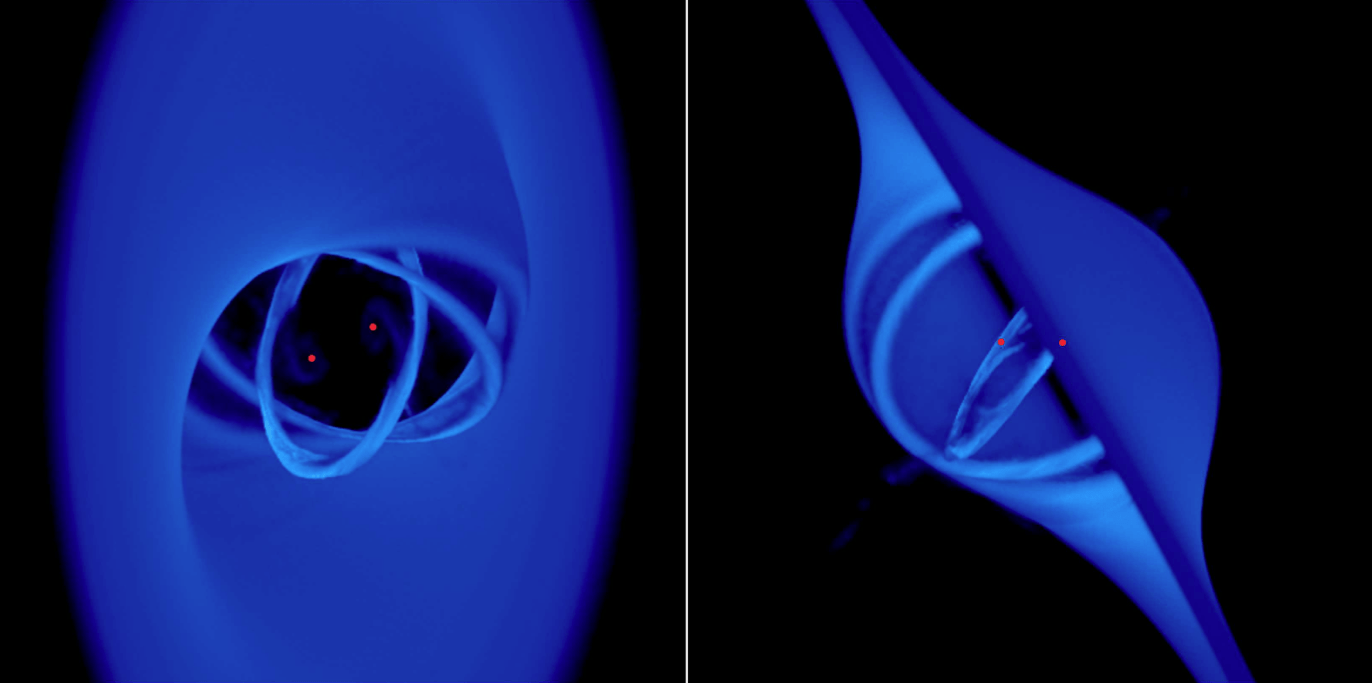

In just a matter of days, the corona — a cloud of particles traveling near the speed of light — fell in toward the black hole. The observations are a powerful test of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which says gravity can bend space-time, the fabric that shapes our universe, and the light that travels through it.

“The corona recently collapsed in toward the black hole, with the result that the black hole’s intense gravity pulled all the light down onto its surrounding disk, where material is spiraling inward,” said coauthor Michael Parker from the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, United Kingdom, in a press release.

The supermassive black hole, known as Markarian 335, is about 324 million light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Pegasus. Such an extreme system squeezes about 10 million times the mass of our Sun into a region only 30 times the diameter of the Sun. It spins so rapidly that space and time are dragged around with it.

NASA’s Swift satellite has monitored Mrk 335 for years, recently noting a dramatic change in its X-ray brightness. So NuSTAR was redirected to take a second look at the system.

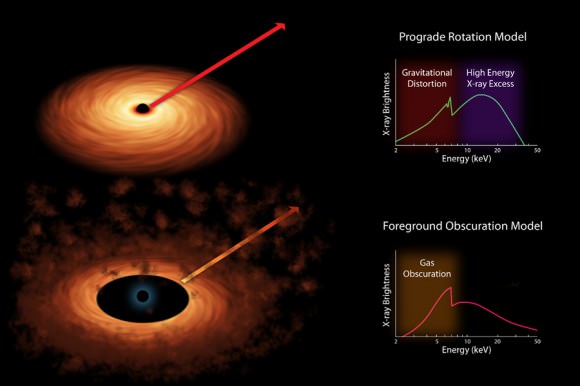

NuSTAR has been collecting X-rays from black holes and dying stars for the past two years. Its specialty is analyzing high-energy X-rays in the range of 3 to 79 kiloelectron volts. Observations in lower-energy X-ray light show a black hole obscured by clouds of gas and dust. But NuSTAR can take a detailed look at what’s happening near the event horizon, the region around a black hole form which light can no longer escape gravity’s grasp.

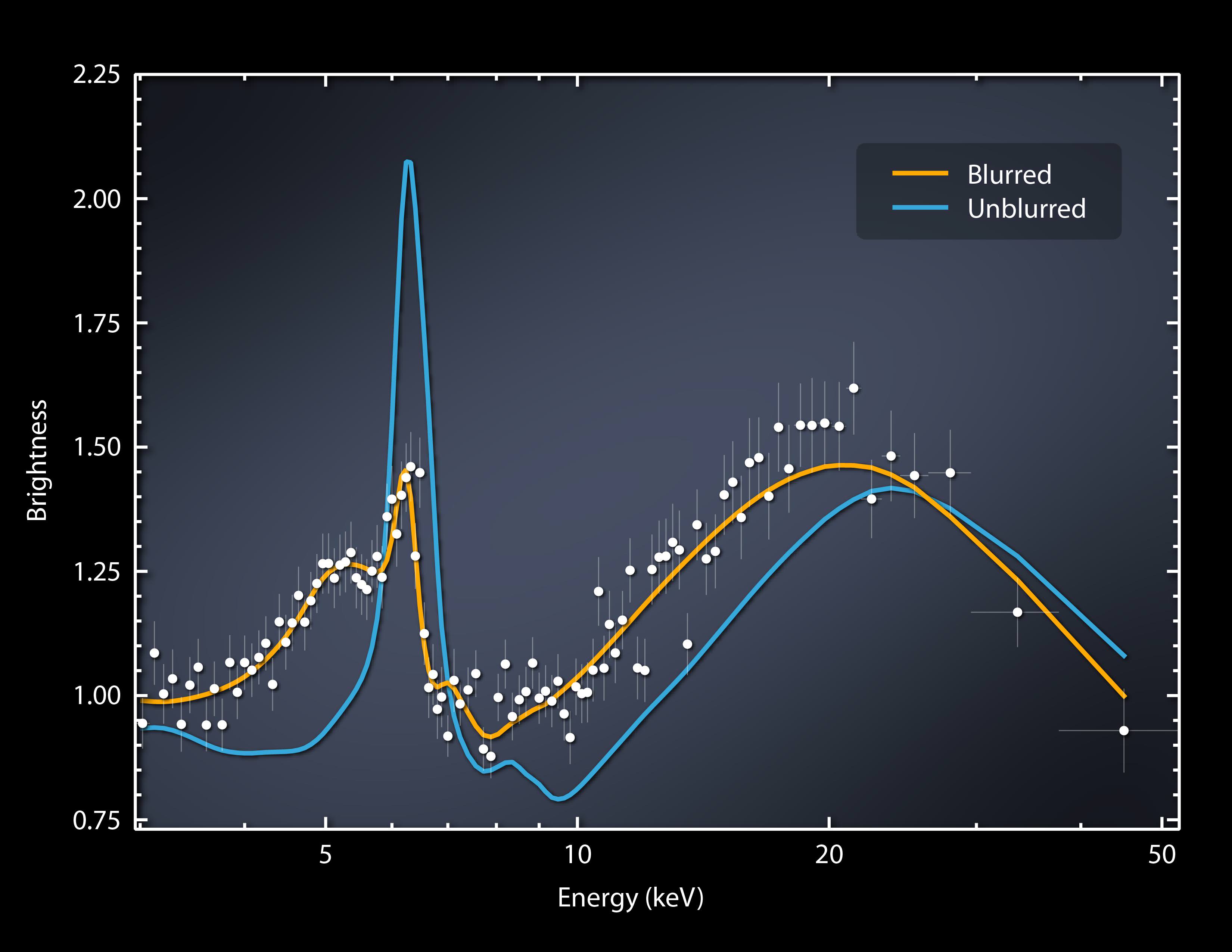

Specifically, NuSTAR is able to see the corona’s direct light, and its reflected light off the accretion disk. But in this case, the light is blurred due to the combination of a few factors. First, the doppler shift is affecting the spinning disk. On the side spinning away from us, the light is shifted to redder wavelengths (and therefore lower energy), whereas on the side spinning toward us, the light is shifted to bluer wavelengths (and therefore higher energy). A second effect has to do with the enormous speeds of the spinning black hole. And a final effect is from the gravity of the black hole, which pulls on the light, causing it to lose energy.

All of these factors cause the light to smear.

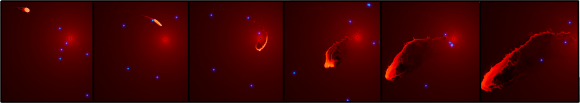

Intriguingly, NuSTAR observations also revealed that the grip of the black hole’s gravity pulled the corona’s light onto the inner portion of the accretion disk, better illuminating it. NASA explains that as if somebody had shone a flashlight for the astronomers, the shifting corona lit up the precise region they wanted to study.

“We still don’t understand exactly how the corona is produced or why it changes its shape, but we see it lighting up material around the black hole, enabling us to study the regions so close in that effects described by Einstein’s theory of general relativity become prominent,” said NuSTAR Principal Investigator Fiona Harrison of the California Institute of Technology. “NuSTAR’s unprecedented capability for observing this and similar events allows us to study the most extreme light-bending effects of general relativity.”

The new data will likely shed light on these mysterious coronas, where the laws of physics are pushed to their limit.

The article has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is available online.