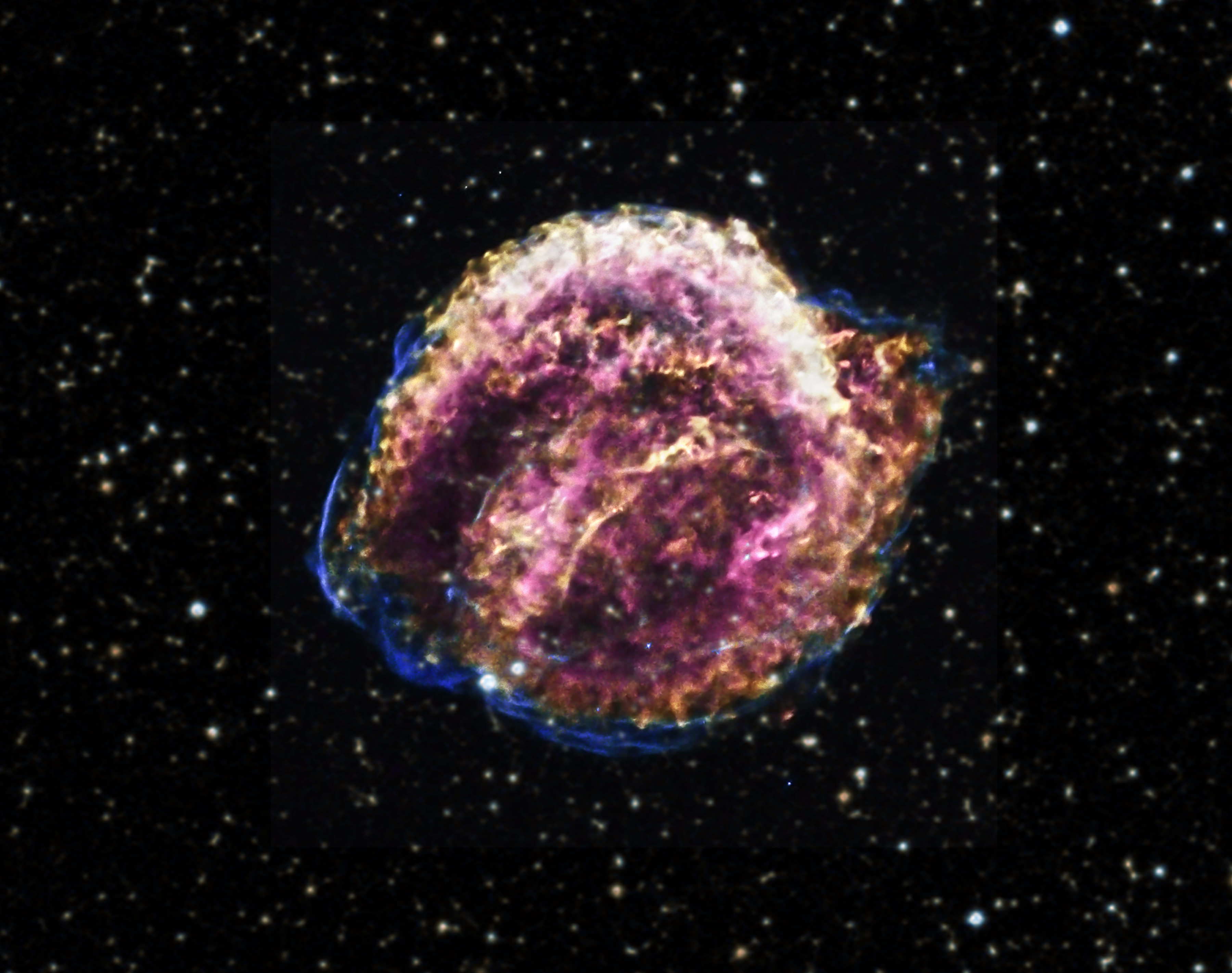

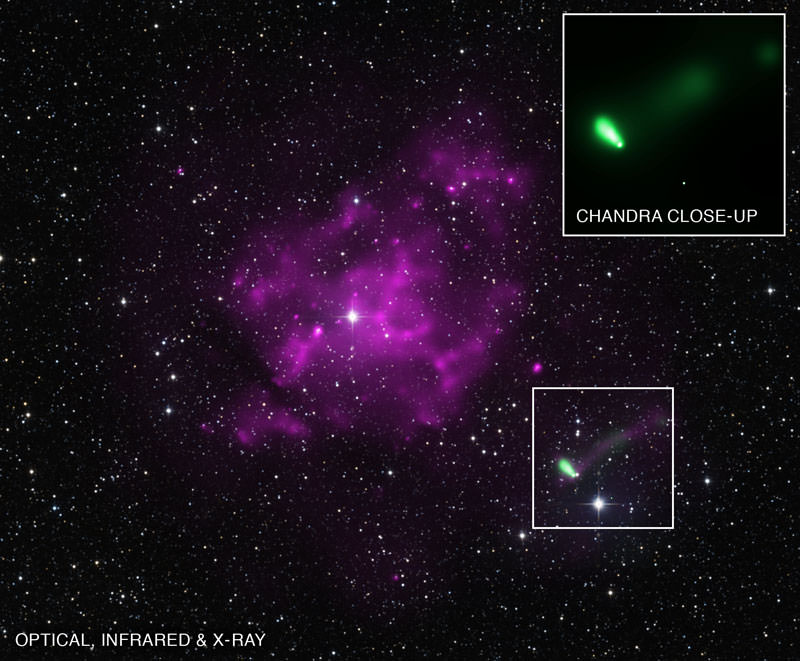

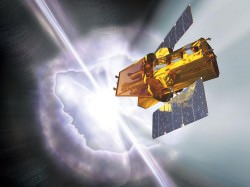

GRB 080913, a distant supernova detected by Swift. This image merges the view through Swift’s UltraViolet and Optical Telescope, which shows bright stars, and its X-ray Telescope. Credit: NASA/Swift/Stefan Immler

The first moments of a massive star going supernova may be heralded by a blast of x-rays, detectable by space telescopes like Swift, which could then tell astronomers where to look for the full show in gamma rays and optical wavelengths. These findings come from the University of Leicester in the UK where a research team was surprised by the excess of thermal x-rays detected along with gamma ray bursts associated with supernovae.

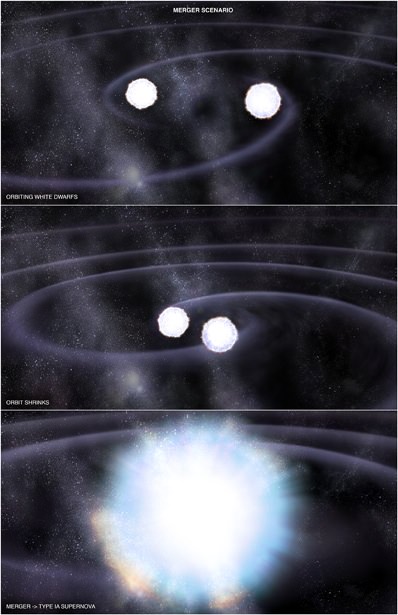

“The most massive stars can be tens to a hundred times larger than the Sun,” said Dr. Rhaana Starling of the University of Leicester Department of Physics and Astronomy. “When one of these giants runs out of hydrogen gas it collapses catastrophically and explodes as a supernova, blowing off its outer layers which enrich the Universe.

“But this is no ordinary supernova; in the explosion narrowly confined streams of material are forced out of the poles of the star at almost the speed of light. These so-called relativistic jets give rise to brief flashes of energetic gamma-radiation called gamma-ray bursts, which are picked up by monitoring instruments in space, that in turn alert astronomers.”

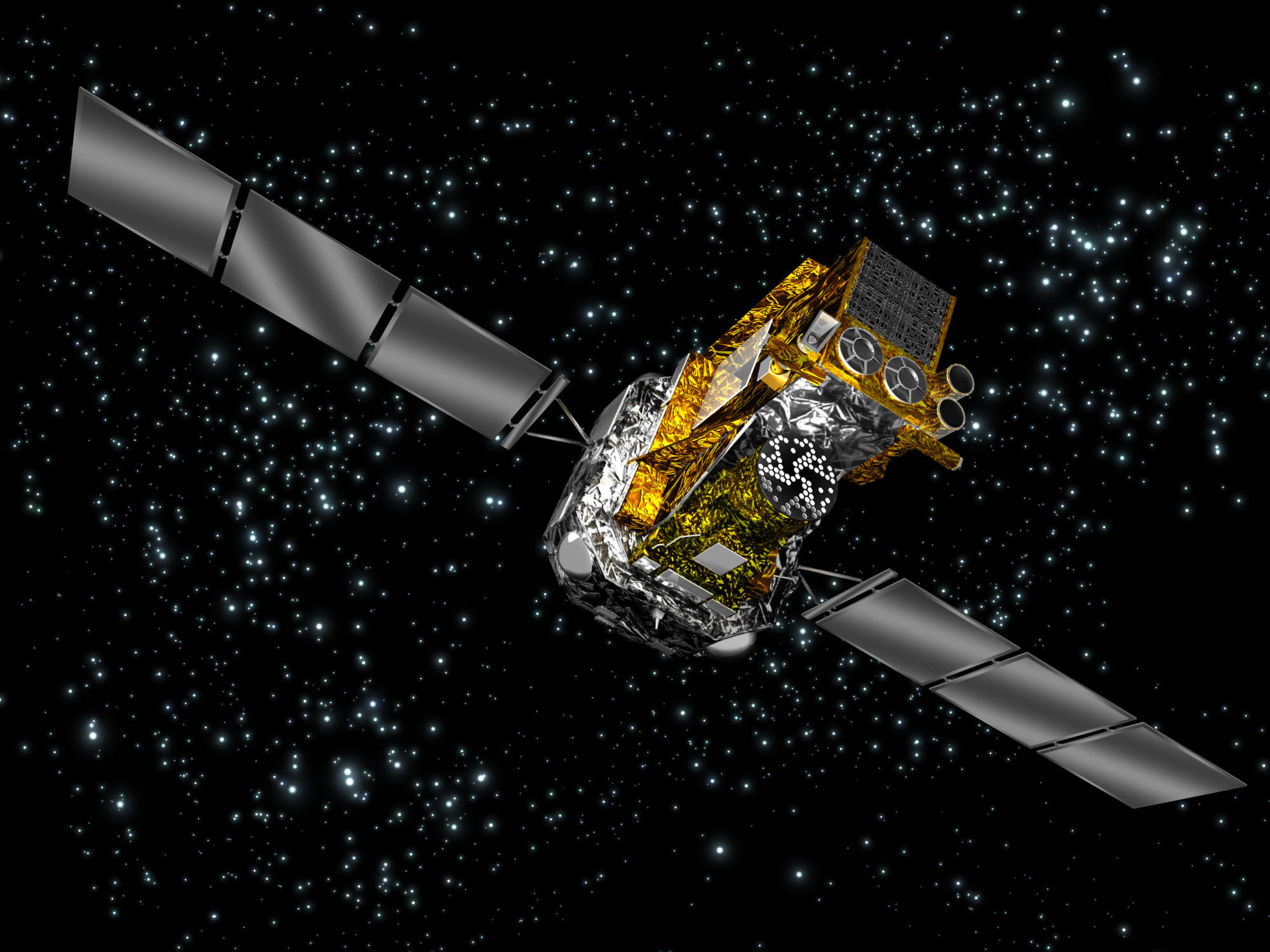

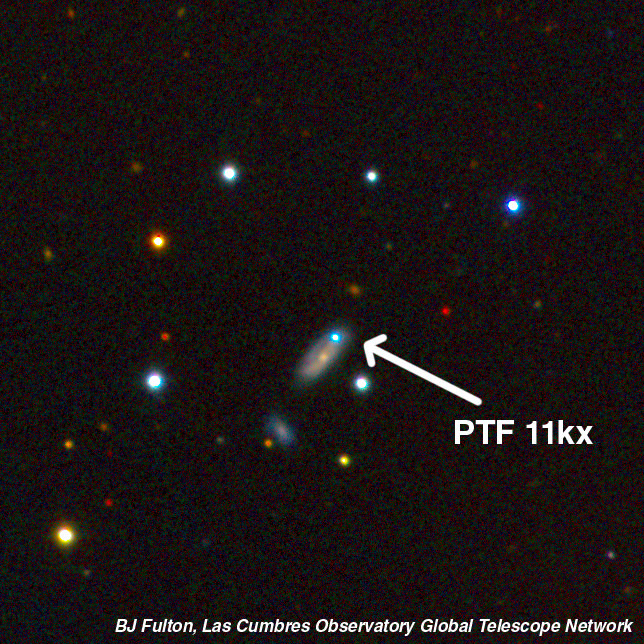

Powerful gamma ray bursts — GRBs — emitted from supernovae can be detected by both ground-based observatories and NASA’s Swift telescope. Within seconds of detecting a burst (hence its name) Swift relays its location to ground stations, allowing both ground-based and space-based telescopes around the world the opportunity to observe the burst’s afterglow.

Powerful gamma ray bursts — GRBs — emitted from supernovae can be detected by both ground-based observatories and NASA’s Swift telescope. Within seconds of detecting a burst (hence its name) Swift relays its location to ground stations, allowing both ground-based and space-based telescopes around the world the opportunity to observe the burst’s afterglow.

But the actual moment of the star’s collapse, when its collapsing core reacts with its surface, isn’t observed — it happens too quickly, too suddenly. If these “shock breakouts” are the source of the excess thermal x-rays (a.k.a. black body emission) that have been recently identified in Swift data, some of the galaxy’s most energetic supernovae could be pinpointed and witnessed at a much earlier moment in time — literally within the first seconds of their birth.

“This phenomenon is only seen during the first thousand seconds of an event, and it is challenging to distinguish it from X-ray emission solely from the gamma-ray burst jet,” Dr. Starling said. “That is why astronomers have not routinely observed this before, and only a small subset of the 700+ bursts we detect with Swift show it.”

Read more: Finding the Failed Supernovae

More observations will be needed to determine if the thermal emissions are truly from the initial collapse of stars and not from the GRB jets themselves. Even if the x-rays are determined to be from the jets it will provide valuable insight to the structure of GRBs… “but the strong association with supernovae is tantalizing,” according to Dr. Starling.

Read more on the University of Leicester press release here, and see the team’s paper in the Nov. 28 online issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society here (Full PDF on arXiv.org here.)

Inset image: An artist’s rendering of the Swift spacecraft with a gamma-ray burst going off in the background. Credit: Spectrum Astro. Find out more about the Swift telescope’s instruments here.